The History Of The Mysterious World Wide Hum Explained

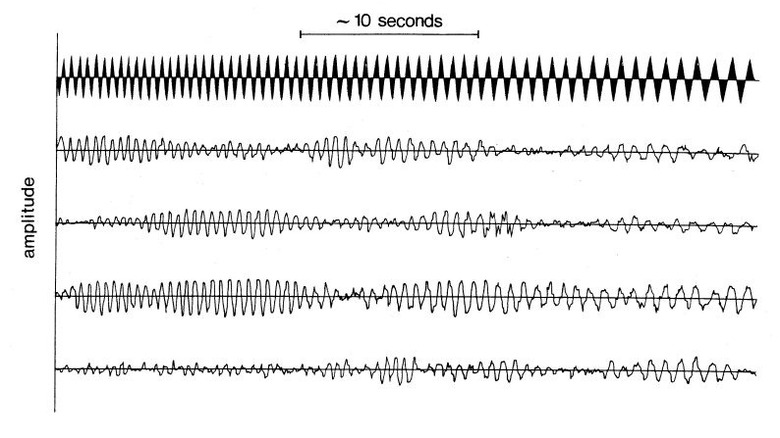

All of us have probably heard something that our friends and family could not confirm hearing. However, it's another matter when select people all over the world say they hear the same type of low "hum" or rumble. This type of noise is considered to be "infrasound," or any inaudible sound that is below 20 hertz and seldom takes place at high sound pressure levels (via National Toxicology Program). In a November 1973 volume of the journal New Scientist, Ron Brown reported on a study by Bruel and Kjaer: "There are many man-made environments ... where the levels of infrasound are sufficient to give rise to physiological and psychological effects which are unpleasant or worse." Even in 1973, however, there were experts that doubted the outcomes of Bruel and Kjaer's tests.

In a summary of literature on infrasound effects by the National Toxicology Program in 2001, researchers found that the most consistent consequence of infrasound on human subjects was annoyance. To cause this, the infrasound has to reach larger levels of sound pressure than higher frequencies of sound. Most of the studies were found to have no agreement on biological effects on humans, yet "workers exposed to simulated industrial infrasound of 5 and 10 Hz and levels of 100 and 135 dB for 15 minutes reported feelings of fatigue, apathy, and depression, pressure in the ears, loss of concentration, drowsiness, and vibration of internal organs."

This infasound "hum" really isn't something to scoff at, affecting people all over the globe.

Taos Hum

In the early to mid 90s, select Taos, New Mexico, residents started to pick up on an irritating, low-frequency hum. This phenomena was not isolated to Taos, but the residents in Taos became outspoken in their uproar about the noise. In 1993, they caused the New Mexico congressional delegation to put together an investigation of the "hum." A group of scientists and professors from the Air Force Base, state universities, and other institutions joined the investigation. Through interviews with "hearers" (those who hear the "hum"), they came up with the attributes that had to be taken into account: the selectivity of hearers, the consistent nature of the hum (they hear it weekly), the widespread nature of it (all over the country, not just Taos), and it being low in frequency like an idling diesel truck or distant pump (via The Acoustical Society of America).

One resident of Taos, Catanya Saltzman — a trained dancer and choreographer — stated that the first time she heard it, she was "awakened in the middle of the night by this sound I could not get away from." It got so bad that Catanya had to quit dancing because it was affecting her inner ear which, in turn, hurt her balance. Her husband Bob stated he has sleepless nights and gets headaches from it. Bob noted the extent of annoyance they had with the noise, "The truth is if we can't get this solved, we're going to have to move" (via People).

Auckland Hum

In Auckland, New Zealand, the hum appears to select people in various suburbs and surrounding towns in the area, but it's unique in its hertz measurement. Dr. Tom Moir, a computer engineer at Massey University's Institute of Information and Mathematical Sciences, pegged the sound through a home recording at 56 hertz, which places it above the infrasound level. Yet, once again, not every person in Auckland hears it. Dr. Moir confirmed the recording with one of his students who is a "hearer" who lives in Whangaparaoa, a 30-minute drive north of Auckland (via The Sydney Morning Herald).

In another report by The New Zealand Herald, Dr. Moir states that for the hearers, the noise is "quite serious to them, it's driving them bonkers. {He] was there at the same time and [he] couldn't hear anything." One hearer got so tired of the noise that he intentionally attempted damage on his hearing by revving a chainsaw right next to his ears. Even Dr. Moir's wife, Jude, could hear the noise and she said it was an "awful noise and sensation," and she added, "It feels creepy. It's not a place I'd like to live regularly." The founder of the New Zealand Tinnitus Association, Joan Saunders, stated that some of those who reported hearing the noise did have tinnitus, but not every one of them did.

Windsor Hum

Right across the Detroit River from Detroit, Michigan, is the city of Windsor, Ontario, Canada, whose residents, too, have been struggling with the noise heard 'round the world. In their case, they seemed to have pinpointed the origin of the humming (or so they think) at Zug Island which is part of River Rouge, Michigan, just south of Detroit. This island holds the corporation U.S. Steel's Great Lakes Works which includes ironmaking facilities. Windsor has been very outspoken and has tried to put pressure on River Rouge to look into it. The Ontario Ministry of the Environment was able to pinpoint the vibrations to about half a square mile around Zug Island, yet "River Rouge said ... it would move quickly to investigate industrial sources for the vibrations, but has since backed off, citing a lack of funds" (via Windsor Star).

The documentarian Adam Makarenko went to Windsor to make "Zug Island: The Story of the Windsor Hum." He was interviewed on the podcast Twenty-Thousand Hertz where he noted that the steel industry has been on Zug Island for a long time; the creation of "pig iron" has not changed in a hundred years, but the hum was not reported until 2011. So that caused a lot of questions for Makarenko and the residents of Windsor. In late 2019, however, U.S. Steel began powering down their blast furnaces and eventually stopping them completely. From that point on, the hum has ceased, according to official reports.

Skepticism

The Independent interviewed Dr. Geoff Leventhall who has investigated these hums since the 1970s and has never heard it himself, yet he reminds readers that "if people say they have a noise problem then they have a noise problem. It is unfair to suggest otherwise. But what might be the cause of it we are not always sure." In the same article, other experts are cited as saying that people "are more antagonistic towards a sound they don't like the source of — such as a wind turbine or a motorway — compared to an equally loud babbling brook or the dawn chorus." This could be plausible in the case of the "Windsor Hum."

Dr. David Baguley, head of audiology at Addenbrooke's Hospital in Cambridge, posits that those who hear these hums have become over-sensitive in their hearing. He says that humans have an internal volume control can be turned down in contexts where we are tense, fearful, or under threat. "Waiting for a teenager to come home from a party — the key in the door sounds really loud. Your internal gain is sensitised." People do this because we need our senses to be on alert; however, Dr. Baguley states that this can become a vicious cycle when we focus on what may be an innocuous sound, the more our bodies tense up and we become fearful. Our internal volume amplifies the sound which only causes more irritation and, for many, annoyance (via BBC News).

Machines?

As talked about in the case of the "Windsor Hum," it does seem likely that many of these cases could be the product of industry and all of the machinery it takes to keep the world moving. Another case that plays into the hands of this explanation comes from Kokomo, Indiana, where residents complained of hearing a hum leading to an investigation which settled on two factories, Daimler Chrysler and Haynes International, as the origin of the hum which, in this case, was even making people sick. The report itself speaks only to the question of the external noises from the factories, but notes that there may be "non-acoustic" factors at play — those noises that instruments cannot measure (via The Kokomo Hum Investigation Report).

This is far from the only "solved" case when it comes to industrialized noise pollution. Another factory in Erie, Pennsylvania, that belongs to Accuride Manufacturing caused many of the surrounding residents to lose sleep and investigate the origins of the sound in the middle of the night. The community filed a complaint with the State Deptartment of Environmental Protection, but it did not investigate claims of noise pollution. However, it did tell them what was making the noise: "a fan installed inside the Accuride plant to address an air quality issue" (via Erie News Now).

Tinnitus?

As in the case of the "Auckland Hum," tinnitus has become a go-to explanation for the hum for many of the cases where no external factor could be found. It's thought that if there is no material origin of sound, then it must be some flaw of the person's or peoples' hearing. According to ENT Health, "Tinnitus is not a disease per se, but a common symptom, and because it involves the perception of hearing sound or sounds in one or both ears, it is commonly associated with the hearing system." There is a multitude of diverse explanations for tinnitus reported in this article which would lead to difficulty in pinpointing the a common thread through all "hearers" in any region unless it was industrial-based.

David Deming wrote an article for the "Journal of Scientific Exploration" which explored the explanations given for the hum and the rationale behind them. In the article, he takes the explanation of tinnitus to task, saying that the noises heard by those with tinnitus and those who hear the hum are categorically different. He quotes the authors of the report on the "Taos Hum": "Most individuals with tinnitus match what they perceive to [be] a tone between 3000 to 6000 Hz, and rarely, if ever, does a tinnitus sufferer match to a tone below 1000 Hz. Why should such a phenomenon skip from regions of the cochlea where the lowest frequencies are represented?"

Spontaneous otoacoustic emissions?

Otoacoustic emissions are small noises the ear makes as a mechanical feature of the cells in the cochlea which then move through the various membranes and parts of the ear. They can be spontaneous in that they both happen in response to no stimulus and they can be "evoked" when there is sound input within the ear. A report in 2000 said that anywhere from "38-60% of adults with normal hearing have spontaneous otoacoustic emissions ... The majority of these people are unaware of this activity" (via Tinnitus). In other words, some who are skeptical of those who hear the hum say that the noise is just a natural internal function of the ear.

When the Los Angeles Times reported on the "Taos Hum," they talked to Joe Kelly about his thoughts about the nature of the hum, and he thinks its a real phenomenon that happens within the internal workings of the auditory system. "The 'sound' may not even be a sound, at least not as it is usually experienced ... [Kelly] suspects a link to the phenomenon of oto-acoustic emissions — low-frequency noises produced by the ear."

Jet stream?

One of the earlier conjectures was the sound of jet streams. "Jet streams are relatively narrow bands of strong wind in the upper levels of the atmosphere." These winds are at the height of their strength during winters of both the Southern and Northern hemispheres. Whenever you hear about hurricanes, then the chances are good the jet streams are involved somehow (via National Weather Service).

In the New Scientist article from 1973, Dr. Joseph Hanlon reports that after a woman threatened to commit suicide due to hearing the humming which no one else around her was able to hear, he went to her place and recorded the "nothing" that he heard himself. Turned out the "nothing" reached a peak of 30-40 hertz which is officially in the realm of human audibility. He suggested that it was the air jet streams moving against slower moving air and that, itself, would make a noise that could reach those levels if it was a cool morning with a light breeze and no sound to cover up the noise. Hanlon goes on to write, "manmade factors might amplify the sound ... Power line posts are just the right size to radiate this sound. Half the people investigated have posts nearby and in some cases the posts were vibrating so much that it was painful to place the ear against them." The sky may in fact be humming some of us a little song.

Fish?

One of the more entertaining possibilities for the cause of the hum comes from underwater. The University of Washington Marine Biology Program came up with their own theory as to what the humming might be in Seattle. They say it is likely the Midshipman fish. "Part of the fish's mating call involves an extended hum. That hum, produced by male Midshipman fish attempting to lure a mate, can last for hours, as males attempt to out-hum potential rivals." That hum then gets amplified off the hulls of boats and buildings and echoed through the city (via Huffington Post).

In Sausalito, California, a community of houseboats in the 1980s found themselves awakened by a sound that could be as light as an electric razor and as loud as an airplane engine. The explanations at the time ranged from secret government submarines to extraterrestrial visitors, but once they were able to pinpoint the origin of the sound, it became clear: the Humming Toadfish. Like the Midshipman fish, these fish hum in order to mate. As the local Sausalito Historical Society explains, "Once they find a suitable nesting spot, these eager bachelors summon likely mates by vibrating their gas bladders up to 150 times a second. The phenomenon has been documented as far back as the 1800s ... Some years they cluster around rocks, other years on concrete houseboat hulls, much to the dismay of the residents."

Earthsong?

Scientists say that the Earth is constantly "vibrating, stretching and compressing." They call it a drone of ultralow frequencies that is impossible for the human ear to hear or feel. They also are not entirely sure what causes the constant movement. One of the theories is the movement of waves over all of the ocean floor, beaches, rocks, etc. It does seem as if it is primed to be a perpetual motion machine. Others say it is the movement of the atmosphere. "And yet scientists are only beginning to understand our planet's hum. They have been limited for years because they only knew how to measure it from land, while nearly three-quarters of the globe is underwater" (via Seattle Times).

National Geographic piggybacks onto this idea in an article about scientists who are attempting to study the hum from the bottom of the ocean. The magazine reports, "by studying the Earth's hum signal from ocean-bottom stations, scientists can map out a detailed landscape of the Earth's interior. Currently, they can only look at the inside of the planet during earthquakes, which limits studies to certain times and areas." This information could lead to detailed maps of the Earth's various layers and core as well as giving us insight into the possible makeup of alien planets as well.

Is it possible there is just a hum that some hear?

David Deming wrote a paper for The Journal of Scientific Exploration about "The Hum" and the literature, causes, and skepticism surrounding the witnesses, and he largely pushes back on all of the plausible reasons to deny the existence of "The Hum" as witnesses define it. For instance, he handles the issue of "confounding factors" like machinery and brings up Kokomo, Indiana, as an example. He notates that after the investigation was done and the two companies worked toward quieting the machines, "people who heard the Hum still suffered ... The acoustical consultant also noted that there were ”non-acoustic” issues involved that went beyond the industrial noise he had located." He also noted that the noises heard by witnesses are significantly different that those heard by those who suffer from tinnitus.

Deming seems to give credibility to TACAMO (Take Charge and Move Out) aircraft that use VLF (very low frequency) bands to communicate with submarines and others vessels. His reason for this is the timing of Hum reports verses significant known TACAMO movements. The beginning of Hum reports in the United States corresponds with the upgrading of TACAMO technology in America. "One of the most mysterious aspects of the Hum is the absolute inability of any person or investigator to locate the source. This inability could be understood if the source were on a moving aircraft subject to random and unpredictable deployments."

Popular culture

Real-life stories of the Hum stretch across the world and generally read as both mysterious and fascinating, so maybe it's no surprise that it's made it into some pretty popular TV shows.

In Season 6, Episode 2 of "The X-Files" entitled "Drive," Fox Mulder gets caught up in a car with a man (played by an unknown-at-the-time Bryan Cranston) who knows that if he stops driving his head will explode like his wife's did. Dana Scully, meanwhile, finds out that the man and his wife had been government test subjects for extremely low frequency (ELF) waves in order to make a form of "electrical nerve gas" (via EXaminations).

It has also made it onto hit show, "Criminal Minds," in the second-to-last episode of Season 13, "Mixed Signals." According to Parade Magazine, in the episode "the Hum actually causes people to do crazy things, so it isn't long before the BAU [Behavioral Analysis Unit] is called in to investigate an UnSub [unknown subject] who is targeting his victims' temporal lobes."