The History Of The Catholic Mass Controversy Explained

On July 16, 2021, Pope Francis issued a papal encyclical called "Motu Proprio," which restricts the celebration of the Latin Tridentine Mass used in Catholic Churches before 1970. Although most American Catholics are generally unfamiliar with the Latin Mass and unaware of Pope Francis' actions, the encyclical has set off a firestorm among those affected. The Conversation has called it the "defining moment" of Francis' papacy. Naturally, Catholic Traditionalists and Latin Mass attendees are not happy with Francis' actions.

So this begs the question: Why is this such a big deal? This conflict pits two wings of the Catholic Church and their supporters — who ultimately disagree on a raft of issues related to the current form of the Catholic Mass — against each other. It is a conflict that goes back to the 1960s, but it finds its origins in the Renaissance, when the Catholic Church moved to unify Catholics behind one mass. Here is the story of the Catholic Mass wars explained.

What is the Mass?

So why is there such a big battle over the form of a Catholic Mass? To answer this question, it is necessary to define what a Mass is. According to Mary Queen of Angels Catholic Church, the Mass is the "central act of worship" of the Latin Rite (aka Roman) Catholic Church. At Mass, Catholics are supposed to receive God's graces and learn about the faith through the readings and the priest's sermon.

The most important part of the Mass is the Liturgy of the Eucharist, when the bread and wine are consecrated and become the literal Body and Blood of Christ (aka Transubstantiation). According to Catholic Answers, a Mass is only "valid" if the consecration is said correctly and to the letter. But that does not negate the importance of the other parts of the Mass, which should be carried out with reverence in an atmosphere of solemnity, per Crisis Magazine. The structure of the Catholic Mass (and its equivalents in Eastern Churches) was set relatively early in Christian history in the second century A.D., as noted in Justin Martyr's "First Apology" (via Catholic Culture) Thus, at the source of the modern-day controversy is the problem of continuity. In other words, is the ordinary Catholic Mass used today in continuity with the original forms of Mass from the early Christian era? Or has it changed? For that, it is necessary to turn to the earliest days of Christianity.

Mass in the early Church

Early Christian writings suggest that the structure of pre-Reformation Christian worship, including the Catholic Mass and Eastern liturgies, has remained relatively constant over the last 2,000 years. St. Justin Martyr's (pictured above) first "First Apology" (via Catholic Culture) provides the earliest description of Christian worship, a common point of contention between competing Christian denominations.

Chapter LXVII of St. Justin's "First Apology" describes that once a week on Sunday, the Christians "all ... gather together to one place" to worship. The service he describes involves readings from the New Testament, the Old Testament ("writings of the prophets"), and the Gospels. The priest would then instruct the congregation and urge them to live out their lives in accordance with what they had heard. Chapter LXVI describes communion, which notes that only those "who [believe] that the things which [are taught] are true" can take communion. In other words, non-Christians could not participate. Bishop Robert Barron's Word on Fire Institute notes that this mirrors the current Catholic Mass and the Eastern divine liturgies very closely with few, if any, structural changes (via USCCB). But although the overall structure has remained constant, the Catholic Church has hosted a surprising amount of liturgical diversity and reform in its history, whose practices all followed Justin's structure, but maintained regional peculiarities.

Liturgical diversity in Catholicism

One of the splits today pits Catholic proponents of "unity in diversity" against their co-religionists arguing for one single, uniform Mass. The former group, from a historical standpoint, can point to the medieval Catholic Church, which supported the coexistence of multiple forms of worship (aka "rites"). Some examples include now-defunct rites such as the English Sarum Rite and the Iberian Mozarabic Rite, used by Arabic-speaking Christians living under Muslim rule. In Northern Italy, the Ambrosian Rite, based in Milan (pictured above) still exists today. These rites all bear close similarity to the Latin Rite but have their own unique features, differing in order of Mass, readings, and varying degrees of Greek influence.

As Fr. Marijan Steiner of the Philosophy Institute of the Society of Jesus in Zagreb notes, there was no single, uniform Catholic Mass in Medieval Europe, which may surprise at first, but makes sense from a Catholic perspective. EWTN notes that the Catholic Church is not "Roman," but universal. In fact, according to Catholic Answers, the term "Roman Catholic" started as a Protestant slur. Thus, nothing precluded liturgical diversity in medieval Catholicism, as long as the rites followed the traditions outlined inherited from early Christianity and rejected heretical innovations. It was the Protestant Reformation that led the papacy to codify one liturgy from Rome that all Catholics would follow, and therein lies the origin of today's Catholic Mass controversy.

The Council of Trent

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, the 16th-century Council of Trent was called to officially codify Catholic doctrine and practice and root out Church corruption to counter the spread of Protestantism in Europe. But the council's most important achievement was the elevation of the Latin Rite Mass (aka Roman), originally codified in the 6th century A.D., to the Mass of the entire Catholic Church in the West. It became known as the Tridentine Mass. The Twenty-Second Session stressed that deviations and abuses running rampant throughout Europe were intolerable and took steps to rectify them. Thus, the Masses could only be in Latin, criminals were banned from serving in Masses, and secular music was forbidden in Mass. Pope Pius V confirmed the council's decision with the encyclical "Quo Primum." Both documents also banned the use of any other Catholic liturgical rites other than the Latin Rite.

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, the council had intended to bring the church into unity by suppressing any regional rites, most famously, the Ambrosian Rite of Milan. But even the Council of Trent could not eliminate the local rites completely. According to "Quo Primum," Pope Pius V allowed for regional exemptions, allowing the Ambrosian Rite to survive, albeit in a greatly reduced form. But by and large, the Catholic world fell in line and adopted the Tridentine Mass. Spanish, Portuguese, and French colonization spread the Tridentine Mass from the Americas to the Philippines, solidifying its status as the Catholic Mass.

Catholicism meets modernity at Vatican II

The Catholic Church experienced a turbulent half-millennium after the Council of Trent. The Church saw its power collapse in the face of the anti-clerical Enlightenment, beginning with the French Revolution in 1789. By 1962, the Catholic Church had to increasingly adapt to secularism and the presence of other religions in its historic heartland. So according to NPR, Pope John XXIII (commemorated on the above Spanish stamp) called the Second Vatican Council (aka Vatican II) to adopt an official church position for the new era, urging Catholics to dialogue with other religions, especially Protestants, and encourage interfaith societal harmony. The most important changes, however, affected the Mass and occurred over a period of several years.

The key Vatican II document relating to the Mass is called "Sacrosanctum Concilium." Most things in it are basic Catholic rules. Priests were not allowed to add, remove, or alter the liturgy while regional differences were limited to enforce unity. But sections C and D contained some more "radical" changes. Although Latin remained the language for all Western-Rite Catholic Masses, the council granted permission for the Mass to be translated for use in vernacular languages under certain circumstances. Section D, meanwhile, opened the door for officially approved "experimentation" with Mass, namely the incorporation of local music and customs into the liturgy. This all came to a head in 1965, when the Vatican decided to jettison the Tridentine Mass to create the current Ordinary Form (Novus Ordo) Mass.

Re-writing the Mass

The liturgy wars center around the role and legitimacy of the Novus Ordo Mass (the one most people know today). Contrary to popular belief, the current Ordinary Form Mass is not a translation of the Tridentine Mass. According to the University of Notre Dame, it was a new Mass that was created from scratch that, to many, was unrecognizable from the old one. The most important differences were as follows. The priest, who in the Tridentine Mass faced away from the congregation, was turned around. Communion wafers, which the faithful were not allowed to touch, could now be received on the hand instead of on the tongue (pictured above). Finally, the new Mass would be in vernacular languages, although Latin could be used at certain points. Generally, the structure of the new Mass followed Justin Martyr's Apology. The devil was in the details.

As expected, the new Mass ignited a firestorm of controversy. Controversial Italian cardinal Annibale Bugnini allegedly claimed that in order to bring Protestants back to Catholicism, the Mass had to be made less Catholic. Therefore, according to the Traditionalist Society of St. Pius X, six Protestant ministers were consulted for the new Mass. Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani took serious issue with their participation. Protestants do not believe in transubstantiation. Thus, any changes that reflected Protestant theology in the consecration would have rendered the whole mass invalid. Ultimately, these concerns were dismissed, and by 1970, the new mass was ready to go.

The 'silly season' of Catholicism

According to Catholic Answers, the greater flexibility of the Novus Ordo resulted in a slew of liturgical abuses — unwelcome "surprises" at Mass. Priests altered the order of Mass and even omitted entire parts of the liturgy. Churches became less ornate and decorated, which Vatican II critic Pierre Lemaire (via Notre Dame) claimed stripped Catholic churches of their beauty and made them "as bare as Protestant houses of worship." Lemaire also noted a marked decrease in reverence for the sacrament of confession. Catholics were no longer confessing their sins but still receiving communion, which in itself is a serious sin. Ultimately, critics feared that Catholicism was attempting to conform to the libertine world of the 1960's, rather than being a fortress of faith and refuge from a sinful world.

The transformation of Catholicism was particularly tangible in the United States among a group of faithful referred to as America's "lost" Catholics. According to Cathleen Kaveny of Commonweal Magazine, critics decried the reduction of religious education to "caring, sharing, and making felt banners" over teaching of hard Catholic doctrine. Although Kaveny notes that some criticism is exaggerated, the statistics suggest that the critics are correct. Belief in Catholic teachings has collapsed even among church-goers. Most tellingly, Pew Research found that less than one-third of American Catholics believe that communion is the literal Body and Blood of Christ, the central dogma of the Catholic Church. Traditionalists have used this to argue that the church should reimpose the Latin Mass. But some decided to go their own way instead.

Catholicism fractures

While most Catholics, even objectors, accepted the new Mass, some defied it. Most notable is the Society of St. Pius X (SSPX). In its own words, SSPX was founded by former Archbishop of Dakar Marcel Lefebvre (pictured above) in 1970 to preserve the "traditional priestly formation." Lefebvre only allowed the Tridentine Mass in the seminary, for which Pope Paul VI suspended him in 1976. When Lefebvre defied the Vatican ban by consecrating four bishops in 1988, John Paul II excommunicated him.

The schism with SSPX is controversial. As is clear from the SSPX website, Lefebvre is seen as a stalwart opponent of Vatican II and defender of the Tridentine Mass. But as usual, the reality is more complicated. Although he opposed the new Mass, the Catholic News Agency notes that Lefebvre signed every single Vatican II document, suggesting that he at least did not object to Vatican II's general direction. A letter published by Traditionalist Catholic Group Tradition in Action claims that he may even have celebrated the new Mass for two years, suggesting that he did not initially oppose it either (at least openly). Of course, he may have simply been obeying papal authority until his conscience drove him to defy it.

According to Catholic News Agency, the Vatican has lately reached out to SSPX and made some progress towards reconciliation. The status of sedevacantists is a thornier issue. According to SSPX, sedevacantists believe that the popes after 1958 are illegitimate, a belief that SSPX rejects. Reincorporating them into the Church is a bigger challenge, as they do not recognize the papal authority they would need to negotiate with.

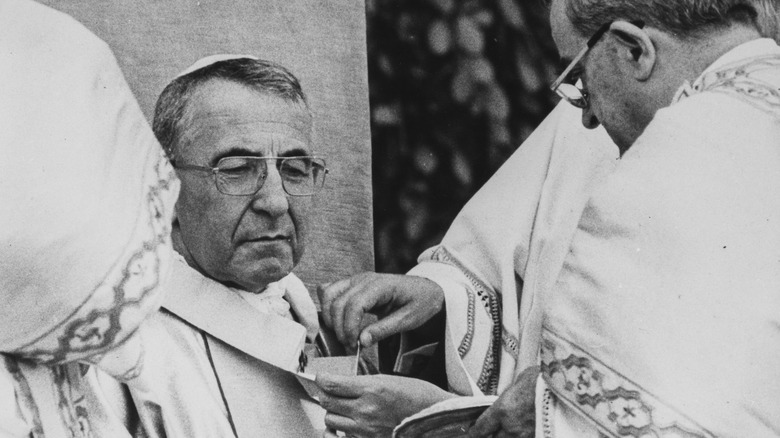

John Paul I's outreach to the Traditionalists

Although some Traditionalists gradually went into schism, others got a chance to influence the church's direction in 1978. That year saw the "people's pope" John Paul I (pictured above) elected to the papal throne. John Paul I is a bit of an enigmatic figure because his papacy only lasted 33 days, ended either by a heart attack or a Byzantine murder plot. He did, however, wish to make the church more accessible to the layman by conveying doctrine in everyday language. The new Mass was part of that. But according to the New York Catholic Traditionalist Movement (CTM), he also wished to keep the continuity between the pre-Vatican II church and the post-Vatican II church. To that end, he enlisted the help of the New York CTM founder, Fr. Gommar DePauw.

A certain mythos surrounds Fr. DePauw in relation to the Mass wars. The Traditionalist blogosphere has claimed that John Paul I tapped Fr. De Pauw to restore the Tridentine Mass. The CTM rejects that claim, noting that no such communication ever took place. But Fr. De Pauw claimed that John Paul I had him in line for a Vatican job to "bring Truth back to the Church." "That good pope," as the CTM calls John Paul I, likely shared Traditionalist concerns that Catholicism was going off the rails after Vatican II, particularly with regards to catechism and liturgical abuse. So it is possible that by enlisting a renowned Traditionalist who was also loyal to the Vatican, he could carry out this agenda in concordance with Vatican II and 2,000 years of Catholic tradition.

The Tridentine Mass returns

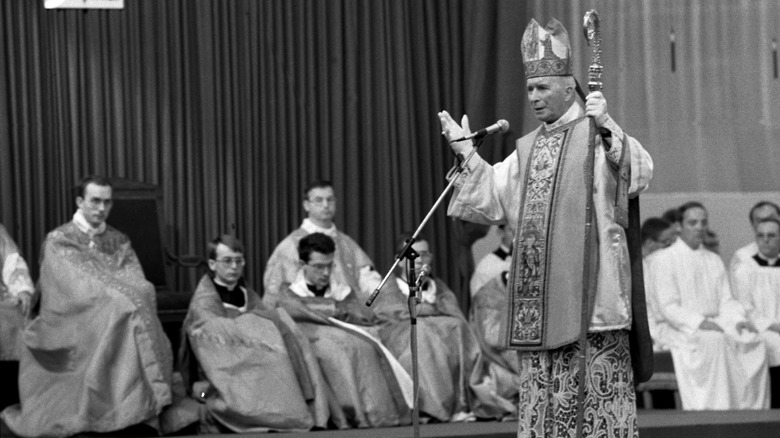

Regardless of John Paul I's intentions, his death halted the implementation of his agenda. The Traditionalists, however, found sympathy with Pope John Paul II's successor, Benedict XVI (pictured above). In 2007, Pope Benedict had issued the papal document "Summorum Pontificium." This encyclical declared the Tridentine Mass and the Novus Ordo as equals and allowed parishes to celebrate the former if enough parishioners requested it.

Benedict's proclamation, despite its intention to end the conflicts within the Church, was hit with criticism from all sides. Fordham University's Sapientia Institute accused the Traditionalists of a holier-than-thou attitude, taking advantage of "Vatican munificence" to tar Novus Ordo attendees as less Catholic. Liberal groups within the church, according to the Irish Times, slammed Pope Benedict for his perceived surrender to "arch-conservative, anti-ecumenical groups" that had opposed Vatican II. Meanwhile, the Traditionalists were not particularly thrilled either. According to Crisis Magazine, Pope Benedict was upholding the "worst abuse of papal power in [Church] history": the creation of the Novus Ordo in place of the old Mass. Giving "permission" to celebrate the old Mass reinforced the perceived abuse of papal power and relegated the Tridentine Mass to second-class status. Finally, there was nothing to stop future popes from re-imposing restrictions on the Old Mass. On this final point, later decisions have proven the Traditionalists correct, as the encyclical had set the stage for the more recent restrictions that Pope Francis enacted.

Pope Francis and Traditionis Custodes

Since Benedict's decision to allow the Latin Mass, the liturgical disputes have intensified. Catholic News Agency notes that certain corners of Catholic Traditionalism and Latin Mass supporters (at least online) have become increasingly vocal in their challenges to the Novus Ordo. Pope Francis (pictured above) has struck back with the papal encyclical Traditionis Custodes. This encyclical does two principal things. First, it establishes the Novus Ordo Mass as the "unique expression" of the Roman Rite, countering Traditionalist assertions articulated in Crisis Magazine. Second, it grants local bishops the right to restrict the use of the old Mass as they see fit.

The papacy has justified the encyclical as a defense of Church unity. Pope Francis has accused Traditionalists and Latin Mass attendees of abusing Benedict's 2007 encyclical to sow division within the Catholic Church and turn the faithful against Vatican II and the papacy. These Traditionalists, he argues, have declared themselves the "True Church" over the 2,000-year old papacy and must be made to fall in line. The restrictions are quite severe. The CNA notes that their devotees cannot use parish churches for their Masses. The readings must be approved vernacular translations, and every Latin Mass group must be vetted for ties to groups critical of Vatican II. They must also be monitored to ensure that they are effective for "the benefit of these faithful [and] ... their spiritual growth," conditions that the average parish is not subject to. This is, of course, assuming that the bishop allows the Tridentine Mass in the first place.

Looking forward

Although bishops such as Cardinal Blase Cupich of Chicago (pictured above with Pope Francis) have stringently enforced and gone beyond Francis' restrictions, others have questioned Francis' decision. The Jesuit America Magazine notes that the restrictions are not conducive to dialogue with Latin Mass Catholics, who have legitimate concerns about the state of American Catholicism. Others, such as Michael Dougherty of National Review, have accused the pope of ripping the Church apart. Pope Francis' encyclical also assumes that stereotypes of Latin Mass Catholics as hateful dogmatists are true. Catholic News Agency notes that the average Latin Mass devotees outside the internet are normal, everyday people whose loyalty to the Vatican will lead them to reluctantly accept the restrictions.

Ultimately, Francis' restrictions may backfire spectacularly. As Pew found, most American Catholics do not believe in the Church's central belief on the Eucharist. And, as the CNA notes, American church attendance has nosedived. In Latin Mass parishes, the reverse is true. The National Catholic Register notes that Latin Mass parishes regularly draw large numbers of millennials and zoomers (Gen Z), many of whom are Catholic converts or reverts. This group cites disillusionment with the increasingly low-attendance-church and irreverent Novus Ordo Masses in favor of the ancient Latin Mass. Although they are a minority (about 1% of American Catholics), some Latin Mass Catholics have a lot of children, making them an important future demographic bloc of 21st-century American Catholicism. With their increasing numbers and influence, Francis' successors will have to engage with them, suggesting that this issue is far from settled.