The History Of NYC's Infamous Five Points Explained

The 19th-century Lower Manhattan neighborhood known as Five Points was notorious. With the rise of cheap tabloid newspapers, stories describing the area's alleged vice, perversion, and violence sold well and spread around the world. The stories didn't come from nowhere. Some of America's most famous gangsters, like Al Capone and Lucky Luciano, came through Five Points. According to Pace University, it is believed that at one time, Five Points had the highest murder rate in the world.

Five Points is probably best remembered today from Martin Scorsese's film, "Gangs of New York", which depicts the organized crime and political corruption that the area was known for. A Christian publication from the time is quoted as referring to Five Points as a "precinct of moral leprosy in the city ... a perfect hot-bed of physical and moral pestilence ... a hell-mouth of infamy and woe."

The "Five Points" refer to an intersection of five streets in what is now Chinatown and Little Italy. As stated in The New York Times, this neighborhood was home for many of New York's immigrants. Their homes were small, cramped, and often unsanitary. The close living quarters led to outbreaks of disease, and the apartments were prone to fires. However, the culture that was born out of the neighborhood was a diverse and fascinating one that changed the future of New York City.

Losing a pond, creating a neighborhood

Once, there was a five-acre lake in Lower Manhattan. It was called the Collect. As described by Tyler Anbinder's "Five Points," it was a beloved natural view for New Yorkers picnicking on Bunker Hill. It wouldn't last.

As the city grew, new regulations were imposed on industries that were loud or made the streets smell. Soon, all of New York City's slaughterhouses and tanneries were located around the banks of the Collect. By the end of the 18th century, the water was so foul and polluted that the city had to address it. Several plans were proposed to deal with the lake-turned-cesspit. The first proposal was to clean the lake and transform the surrounding area into a park. Another was to connect the Hudson River and the East River with a canal that would go through the Connect. Neither would end up happening.

In 1802, Bunker Hill was demolished and the dirt used to fill in the lake. While the Collect appeared to be gone, it would continue to impact the neighborhood built on top of it. The damp earth was believed to encourage the spread of disease, and buildings built on it were unsteady and would settle at odd angles over time.

Immigrant enclave

The majority of people who lived in Five Points were recent immigrants from Ireland, Italy, or China. There were also many Jews, Black people, and German immigrants (although, as described in Claudia Milne's article, by the year 1840 the original, thriving Black community along the shores of the Collect had been transformed into the infamous Five Points). It's also worth noting that, per "Five Points," some have argued that prejudices about the inhabitants of Five Points distorted depictions of the neighborhood.

The very first wave of Italian immigrants arrived in the 1840s, with even more arriving in the 1880s. As stated in "When Little Italy Was Big," many came to live in an area of Five Points known as Mulberry Bend. This first "Little Italy" was home to thousands of recent Italian immigrants. Around the same time, as explained by the Library of Congress, the city quickly became home to millions of Irish immigrants who faced discrimination and were barred from many of the city's better paying jobs. Many were forced into the cheaper housing that was available in Five Points.

And per "Five Points," most Chinese immigrants lived East of Five Points prior to the Civil War. By the 1870s, however, the area around Baxter Street was referred to in the New York Tribune as the part of the city "in which all the Chinese live." After most of the other immigrant communities had diffused throughout the rest of the city, the Chinese remained. Over time, what remained of Five Points would become Chinatown.

Tenement housing

While Five Points was a neighborhood many New Yorkers avoided, others had nowhere else to go. Despite the poor living conditions, there was more demand for housing in the neighborhood than the apartments could handle, so many building owners divided the apartments into tiny cramped living quarters known as tenements.

Some of the buildings turned into tenements had never been residences before. Along with basements and attics, there were former stables rented out as apartments. As described in "'All That Is Loathsome' Life in the Five Points Slum," the tenements resulted from dividing up other buildings. They were all prone to leaks and infestations, but the apartments that were near the front of the building were preferable to those in the back. Front apartments had windows that let in light, whereas those at the back were dark. In 1890, Jacob Riis released "How the Other Half Lives," which described tenement bedrooms (via "'All That Is Loathsome' Life in the Five Points Slum") as being six-and-a-half feet by seven feet. One floor plan was described as showing "twelve living rooms and twenty-one bedrooms, and only six of the latter have any provision or possibility for the admission of light and air."

"Five Points" states that there were brick tenement buildings and wood tenement buildings, the latter of which were extremely prone to fires and not connected to sewers which sometimes caused outhouses to overflow, sending sewage into the basements. The brick buildings, while less likely to be engulfed in flame, were poorly ventilated, and disease could spread rapidly.

Crime rate

Tabloids thrived on stories of deviance and violence in the Five Points. While these stories were told to scandalize New Yorkers in wealthier neighborhoods, the people who called Five Points home, already struggling with miserable living conditions and the threat of disease, were at risk of violent crime.

As stated by Pace University, some sources claim that at one time, Five Points had the highest murder rate on the planet. It was claimed that there was an average of 15 murders every night. One tenenment called The Old Brewery, which housed more than 1,000 people, was reported to have a murder every night. Some historians believe that these were exaggerations, and as the tabloid newspapers of the time were notorious for valuing a good headline over facts — and prejudices against the Black, Jewish, and immigrant populations of the neighborhood may have colored perceptions of Five Points — it is difficult to determine how dangerous it truly was.

What is known is that Five Points did have a significant amount of organized crime. Gangs like the Roach Guards, Bowery Boys, and Dead Rabbits had significant control over Five Points — and some of New York City's most infamous mobsters got their start there. They were also responsible for some of the city's most notorious riots.

Hard work

While painfully small tenement housing made living cheaper in Five Points than in wealthier New York neighborhoods, many of its residents struggled to get by. Many were under-educated for white collar work. Biases against hiring Black people, immigrants, Jews, and Catholics made it difficult for Five Pointers to get high paying jobs. This meant they had to work long hours at physically difficult jobs to get by.

As detailed in "Five Points," 49% of Five Points men were classified as skilled manual workers, including tailors, shoemakers, and other craftsmen (although the majority were kept out of higher-paid trades like woodworking). Another 40% were designated "unskilled workers," such as sailors and waiters. Almost half of the women in Five Points worked as seamstresses. Beyond that, ethnic background influenced the careers available to Five Points residents. Jews were likely to work as tailors and glaziers. Black men and Irish immigrants were more likely to have "unskilled worker" jobs than their German counterparts.

The children of Five Points also worked to support their families. Young girls were often street vendors in the summer and street sweepers in the winter. Young boys were typically shoe shiners or newsboys shouting out headlines in an attempt to sell the daily paper.

Entertainment

The people of Five Points may have had to work long difficult hours to get by, but the neighborhood also offered all kinds of entertainment, from bare knuckle boxing to tap dancing. Despite the reputation for violence that Five Points had around the world, many New Yorkers flocked to the neighborhood after a long day of work. As detailed in "Five Points," the Bowery was a street in the neighborhood, and it was even once referred to as, "the greatest street on the Continent, the moist characteristic, the most American, the most peculiar."

Five Points merchants pioneered the use of lit up signs and displays, so it was always lit up at night. There were numerous bars. People played billiards and bowled. Street vendors and peddlers lined the streets selling treats like baked pears and hot yams. Entertainment like "Punch and Judy" shows were performed. People swallowed swords, juggled, and played instruments.

As explained in the New York Times, parties held in cellars were popular. Along with gambling and drinking, dancing was common. It is believed that, due to the eclectic mix of cultures that could be found in Five Points, tap dancing may have been invented at these parties.

Five Points elite

In the early 19th century, most political decisions were made by the elite. In New York, this typically referred to merchants and manufacturers who were elected into office by their wealthy neighbors. As explained by "Five Points," this power structure was weakened when all white males gained the right to vote. There were very few wealthy New Yorkers still living in Five Points by this time, meaning that the "elite" of Five Points were very different from their counterparts in the rest of the city.

Popularity was the way to become an elected official for Five Points, which explains why many of the most politically influential people in the neighborhood were bar owners. The police force was powerful and had the power to sway elections. Elected officials ensured they would stay in power by employing young men who had campaigned for them. Being a policeman was one of the best paying jobs a Five Pointer could get, so they typically were loyal to those who hired them. Another way to become politically successful in Five Points was the volunteer fire department. It operated almost like a gang, intimidating voters and promoting their own candidates.

Grocers also had a degree of influence, partially because they sold alcohol, and partly because some of the neighborhood's most powerful gangs gathered in their stores.

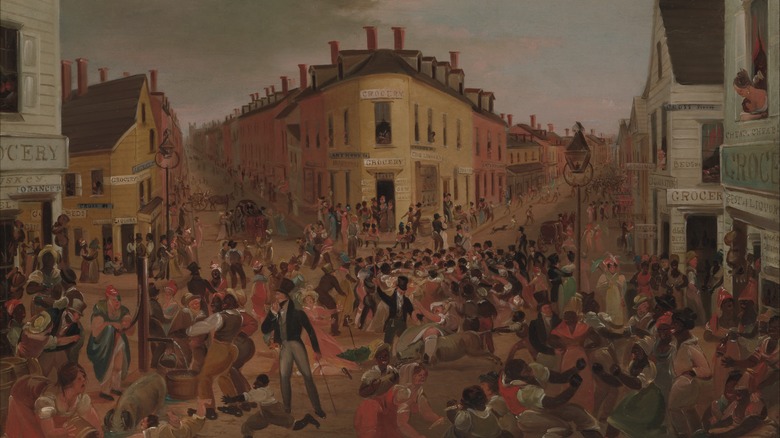

Roach Guards, Dead Rabbits, and Plug Uglies

Another way Five Pointers gained power and respect was by being a member of one of the neighborhood's street gangs, like the Dead Rabbits, Roach Guards, Plug Uglies, Bowery Boys, or Shirt Tails. As stated in "The Gangs of New York: an Informal History of the Underworld," many of the groups met and organized in grocery stores, which led many New Yorkers to view these shops as degraded and dangerous locations.

The gangs' memorable names were inspired by many things, but a few referred to the clothing favored by the gangs. The Shirt Tails never tucked in their shirts. The Irish Plug Uglies wore large "plugs" or bowler hats, which they would fill with wool to protect them when they got into fights.

While the Roach Guards were named for a liquor seller rather than clothing, they wore blue stripes on their pants to distinguish themselves during brawls. During one Roach Guard meeting a fight broke out. One furious member tossed a dead rabbit into the middle of the room, leading to a new faction known as the Dead Rabbits. They gave up their blue stripes and instead carried dead rabbits on pikes.

Riots

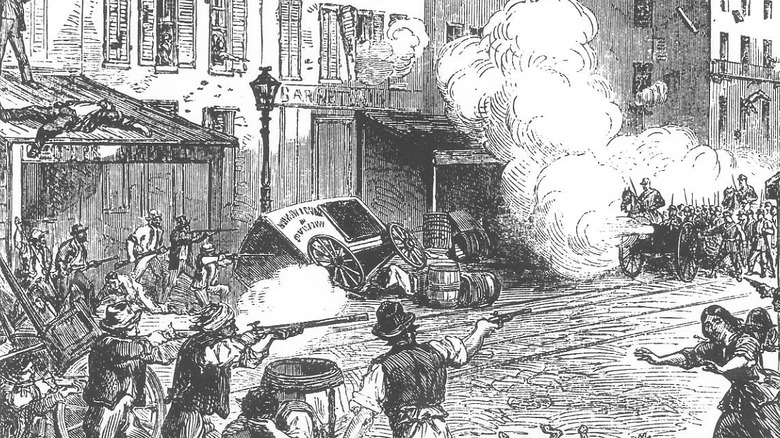

With gangs vying for political power in the neighborhood, Five Points was sometimes overwhelmed with fighting in the streets. These riots sometimes spread to the rest of the city, sending New York into chaos.

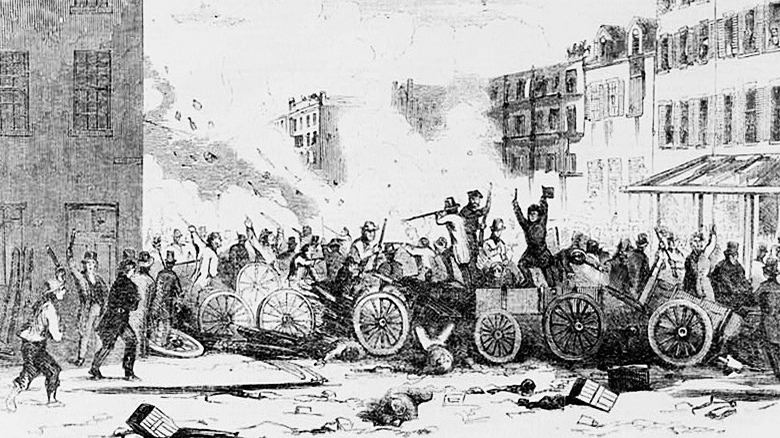

As explained in "Five Points," in 1857, riots broke out over the re-election of Mayor Fernando Wood. Despite the conflict, Wood took office, but his political rivals passed new legislation specifically to target the mayor and his supporters. These included disbanding the city police to be replaced by one that was controlled by a board appointed by the state. The new police department was created, but Wood wouldn't disband the original police force. At one point, on the City Hall steps, the two police forces had an all out brawl. Ultimately, Wood was forced to remove the old police force, and on the morning of the 4th of July, a massive riot occurred. The various Five Points gangs turned out, with the Dead Rabbits (or maybe the Roach Guards) fighting the Bowery Boys.

The New York City Draft Riots also grew out of tensions between the Black and Irish populations of the Five Points. As explained by CUNY BCC, Black and Irish Five Pointers were in competition for the few low paying jobs available to them. After the Civil War began, many Irish men living in New York City were called for the draft. They were furious that they were going to be forced to fight, and they took that rage out on the Black citizens of Five Points.

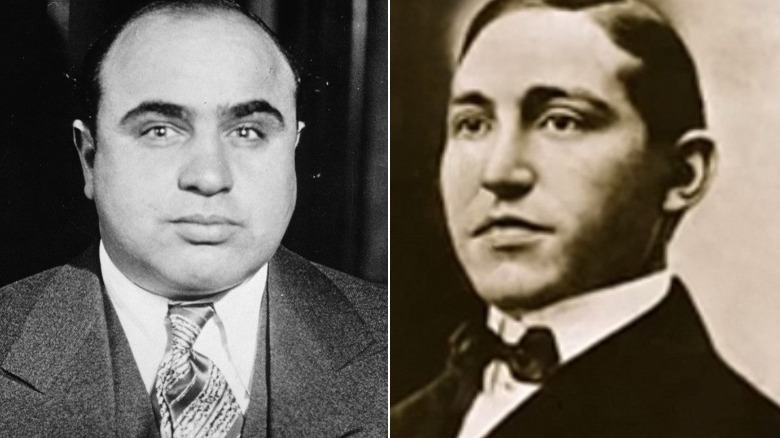

Paul Kelly and Al Capone

Some of the most famous gangsters to come out of New York City got their start in the FIve Points. Future powerful bootlegger kingpins in the era of prohibition like Johnny Torio, Frankie Yale, and Lucky Luciano were all at one time members of the Five Points Gang.

The most powerful gangster in Five Points was probably Paul Kelly. Now well known for the fictionalized portrayal in Caleb Carr's novel, "The Alienist," Kelly was a notorious criminal in the Five Points. As stated by Bloodletters & Badmen, Kelly was a Sicillian immigrant who first found success as a boxer. He took his prize money and opened several brothels. Soon, he had started the Five Points Gang.

As detailed in Britannica, Al Capone — who was sometimes known as "Scarface" — actually got his scar while working for the Five Points Gang. When he was still a teenager, he was slashed at the Harvard Inn near Five Points, leaving a scar down the left side of his face. As quoted by Pace University, when Capone was finally convicted in 1931, he told reporters, "I shoulda never left Five Points."

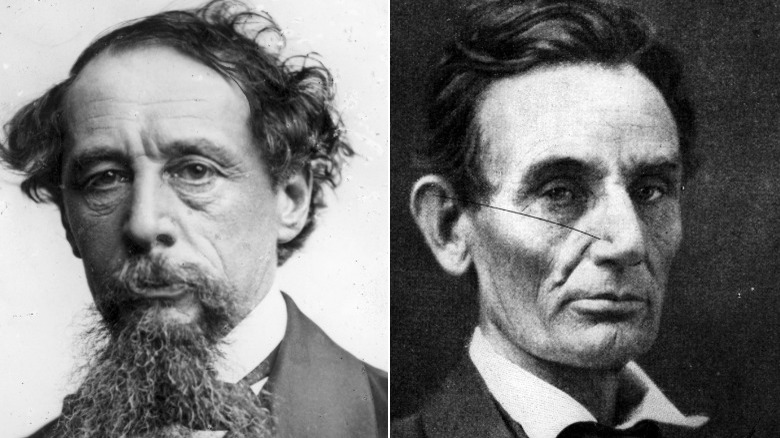

Abraham Lincoln, Charles Dickens, and Davy Crockett

Despite the neighborhood's reputation (or more likely because of it) some of the era's most famous individuals visited Five Points. In 1834, famous frontiersman Davy Crockett, who had fought in the Creek War, stated in his own observations of the area that he would rather fight in a war again than go out after dark in Five Points.

Charles Dickens was no stranger to poverty. As described by Historic UK, his family experienced extreme poverty and his father spent time in "debtor's prison." As an adult, the famous author managed a home for homeless women (as detailed by The Guardian.) Despite his experience, he was shocked by what he found in Five Points. In 1841, Charles Dickens described seeing "poverty, wretchedness, and vice" on his visit to Five Points.

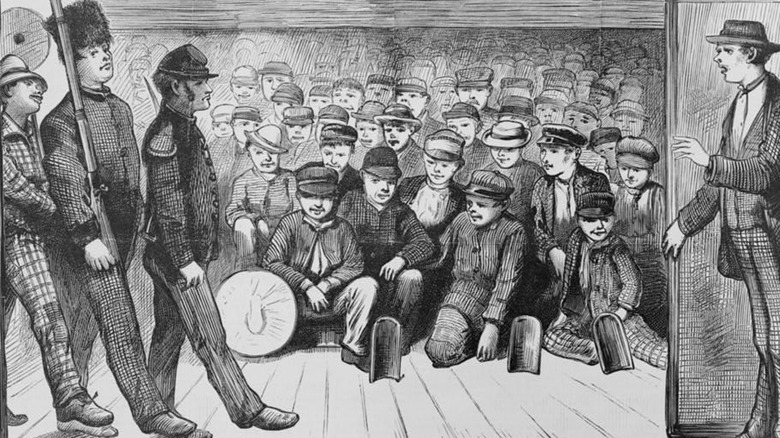

About a year before he was inaugurated as president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln visited the Five Points House of Industry. According to "Five Points," Lincoln was shocked by the poverty he found there. He visited the dorms where homeless children lived and the workshops where teenagers learned trades to support themselves. A teacher asked Lincoln to speak to his students, and at first he refused, stating that he couldn't give children dealing with such hardship any advice that could help them. When pressed, he encouraged the children to always do the best they could. He cut his speech short, too overcome with emotion to continue.

Destruction and demolition

In 1890, journalist Jacob Riis published "How the Other Half Lives." This exposé revealed the living conditions in New York City's most densely populated areas, including Five Points. Riis was concerned about the public health risk of overcrowded tenements (via the Library of Congress). Along with the photographs (a major turning point for American photojournalism), Riis wrote about poor water quality, infestations, child mortality rates, and the disease outbreaks that spread through tenements. The book led to public outcry and demands to clear Five Points. Riis was a friend of then-governor Theodore Roosevelt, who created the Tenement House Commission.

Calvert Vaux (best known for his work on Central Park) planned another park – Mulberry Bend or Five Points Park. The park opened in 1897, replacing tenements with grass and trees. Riis described it as, "little less than a revolution." As "Five Points" explains, clearing Mulberry Bend was the start of a trend of tenements being demolished, and much of the Lower East Side was torn down. From 1867 to 1901, the city put increasingly strict laws in place about ventilation and sanitation, which no tenement in the Five Points lived up to.

The bars, slaughterhouses, billiard halls, and tenement houses were ultimately demolished and replaced. This was done so extensively that tearing down tenements has been referred to as "the New York approach." A single row of brick tenement buildings located near Chinatown is all that remains of the once notorious Five Points.