The Long History Of Vaccine Mandates In America Explained

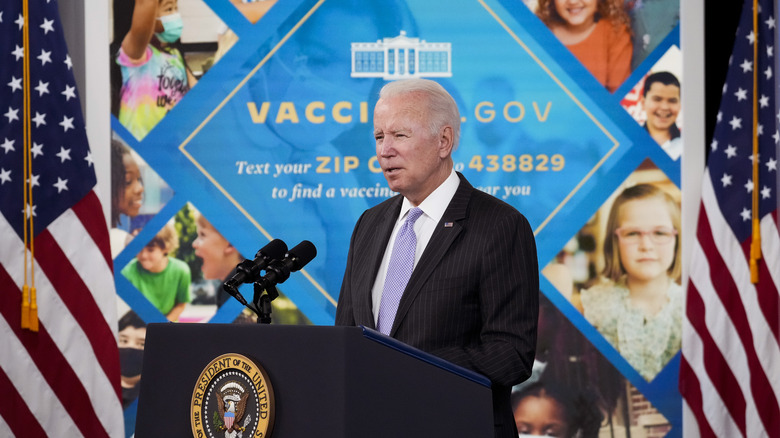

United States president Joe Biden's 2021 vaccine mandate set off a firestorm of controversy across America, as businesses and states rushed to comply before fines set in. There was fierce opposition to the mandate, which fought back with lawsuits and legislation blocking any federal enforcement at the state level.

One of the key aspects of the opposition has centered around the legality of the vaccine mandates, which critics hold could be unconstitutional or unethical. Supporters, meanwhile, point to America's long history with vaccine mandates, which the NY Times called "an American tradition." Both sides bring valid legal, scientific, and historical arguments to the table that cite the tug-of-war between proponents and opponents of mandates.

Contrary to the often simplistic, polemical arguments seen in the media, on the internet, and in political circles, the history of American vaccine mandates is far from straightforward. It is fraught with controversies and relates to some of the uglier moments in the nation's history. Here is the complex and convoluted history of American vaccine mandates.

The 1777 forerunner

The history of immunization mandates in the United States goes back to before the country was officially recognized. In the colonial era, smallpox was one of the world's most devastating diseases. According to the CDC, it had a death rate hovering around 30%. Among Native Americans, who had no immunity to the disease, the death rate may have been around 90%, per Jared Diamond's "Guns, Germs, and Steel."

According to the Library of Congress, outbreaks of disease caused around 90% of all American Revolution deaths and hamstrung the war effort and contributed to a failed American invasion of Canada. But there was a possible remedy. According to Britannica, populations from Europe to the Pacific had developed a primitive immunization technique called variolation. It was noticed that healthy individuals who inhaled dried out smallpox scabs that were ground up tended not to suffer the worst effects of the disease. General George Washington's British opponents had embraced the practice and were mostly unaffected by the disease. So in 1777, Washington decided variolate his forces, despite Congressional prohibitions on the practice.

Washington faced a major problem. About 75% of his men had no exposure to smallpox and were likely to resist variolation, which basically involved infecting them with a milder case of smallpox. Contamination could result in full-blown smallpox outbreaks before the process was complete, so naturally, there was resistance, especially among religious groups and certain physicians. So Washington conducted the operation covertly, and it worked. As a result, the Continental Army's regulars never faced another outbreak that incapacitated its ability to fight.

1809 mandate

According to the journal Quality and Safety in Healthcare, Founding Father Benjamin Franklin was suspicious of variolation. That is, until he lost a son in 1736 to smallpox. Franklin bitterly regretted not inoculating his child, and perhaps others did as well, but their concerns were well-grounded. Variolation was not the safest way of immunizing a patient and could expose them to the full disease. But by 1798, the situation had changed. According to the BBC, Edward Jenner realized that exposing people to smallpox's relative cowpox also immunized them against smallpox. This method was much safer than direct exposure and saved countless lives in Britain.

Once the safer alternative became available in the United States, individual states realized the life-saving potential it had. So according to the American Journal of Bioethics, Massachusetts decided to override individual concerns about the vaccines in favor of public health with an 1809 law that constitutes the first true American vaccine mandate. It was not, however, a statewide mandate. Instead, it allowed local health boards to mandate smallpox vaccinations for the inhabitants within their jurisdictions and penalize refusers with a $5 fine (~$110 today).

To encourage refusers to comply, the town of Milton publicly repeated Jenner's famous (and ethically questionable) experiment on James Phipps that had led to the vaccine's discovery. The town vaccinated a cohort of children in July of 1809. According to the Smithsonian, 12 of those children were publicly exposed to smallpox, but did not get sick after 15 days. This helped assuage safety and efficacy fears regarding and led the town to declare that smallpox "was slain."

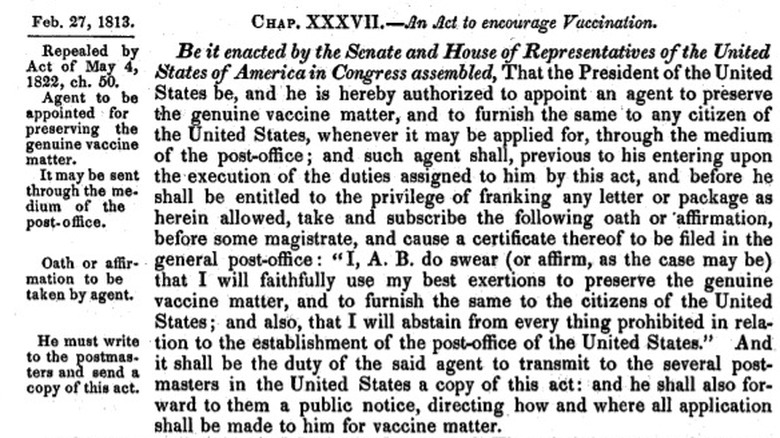

The Vaccine Act of 1813

According to lawyer Rohit Singla (via Harvard Law), the early United States was keen to get its population vaccinated against smallpox. But with approximately 6 out of 7 million Americans dispersed across the countryside in 1810, there were infrastructure and access problems that hindered any vaccination campaign. Rural doctors complained that supplies of Edward Jenner's vaccine were inaccessible, particularly out in the Western Territories. So the United States government stepped in to try and solve the supply issue.

In 1813, the United States decided to imitate England's National Vaccine Establishment and create a government agency through the Vaccine Act responsible for maintaining and administering Jenner's vaccine. The act was the brainchild of Baltimore doctor James Smith, who volunteered to vaccinate the public on Congress' behalf free of charge using a national stockpile as a "National Vaccine Agent." Congress would subsidize Smith's distribution of the vaccine to any willing U.S. citizen through the postal service.

But the creation of "National Vaccine Agents" undermined the Constitution's separation of powers and the power of states to regulate their public health. Giving such power to the government undermined the authority of local doctors to vaccinate their patients. The act was repealed after an 1821 smallpox outbreak in North Carolina that resulted from a faulty batch from the federal stockpile. This turned into a major embarrassment for the federal government, which voided the act a year later and returned the power over vaccination to the states.

1855 Massachusetts mandates

With the failure of the 1813 Vaccine Act, Massachusetts once again took over as leader of government mandates. According to a 1932 report from the Massachusetts Medical Society, the state repealed all mandatory vaccination laws and stopped the tracking and quarantining of smallpox patients, and rescinded all fines for non-compliance in the 1830s. Private organizations, however, were allowed to maintain their mandates. Because smallpox was so deadly, though, the state restored tracking and fines by 1838.

Once the vaccination laws were repealed, the MA Medical Society notes that deaths shot up. For reference, between 1813 and 1838, there were 39 smallpox cases, while between 1839 and 1855, there were over 1,000. Thus in 1855, the state passed a sweeping mandate that is best known for being the first school vaccination law, although it covered much more than that. The 1855 law required all children to be vaccinated by the age of two or face a yearly $5 fine. Unvaccinated children were also barred from public schools. Local health boards, meanwhile, could mandate vaccination for all people under their jurisdiction, although the enforcement mechanism is unclear.

The mandate had a second part. All employees and beneficiaries of state institutions, including public schools, jails, mental hospitals, and any other entity that received state money had to be vaccinated against smallpox. This law formed the basis of future mandates across the country, but it sparked robust opposition that sought the repeal of compulsory vaccination laws as early as the 19th century.

Opposition to mandatory vaccination

Mandatory vaccination laws were already causing problems in Massachusetts for adults, but opposition, which had existed since the early 19th century (pictured above) intensified once the school vaccine laws came into force for children. Thus, along with vaccine laws came vaccine exemptions. According to the Massachusetts Medical Society, critics complained that the vaccination mandates infringed on personal liberty and subjected "their patients to the provisions of severe and as they believed unnecessary laws." In practice, this referred to provisions requiring doctors to report cases of parental neglect to vaccinate children against smallpox so that fines could be issued. However, critics also took issue with smallpox case tracking and quarantines, despite the extremely high death rate from the disease.

Opponents succeeded in repealing the vaccination and disease control laws of the late 18th/early 19th century in 1838. But, they returned in 1855 with a newborn mandate that required vaccination for children under two or a $5 fine. But there was enough resistance to make the mandate unfeasible, because in 1884, the legislature caved in to critics. Unvaccinated children with a doctor's note were allowed to attend public school as long as they were not exposed to smallpox inside the home. Opponents pushed back with help from newly-formed societies such as the Anti-Vaccination Society of America (via History of Vaccines) and its descendants, who solidified the exemption in 1908 and eliminated the newborn mandate. But there was still the problem of fines for refusing adults, which came to the fore in a famous – or to some, infamous – Supreme Court case in 1905.

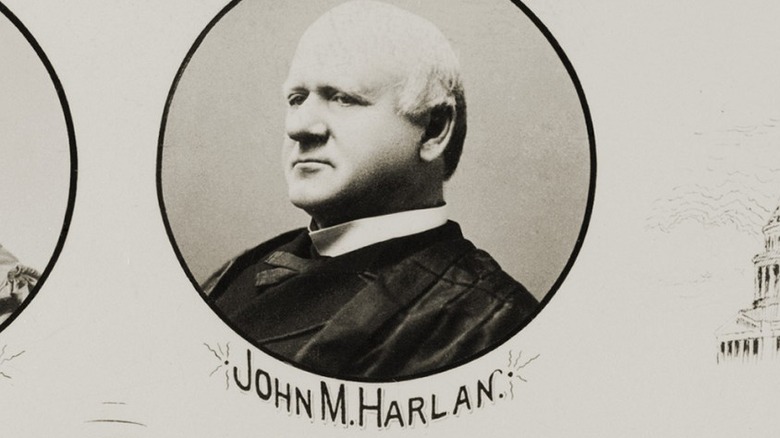

Watershed: Jacobson v Massachusetts

The battle over vaccine mandates arrived at the nation's highest court in 1905 and involved, as always, the state of Massachusetts. The case Jacobson v. Massachusetts, according to the American Journal of Public Health, pitted Swedish-born Lutheran pastor Henning Jacobsen against Massachusetts and its fines for refusing smallpox boosters. Jacobson had good reason to refuse. He had suffered adverse reactions to the smallpox vaccine in the past. But refusal would cost him a $5 fine (~$140 today). Jacobson had no interest in paying, arguing that Massachusetts was infringing upon his personal liberties despite his documented and legitimate reasons for refusing smallpox boosters. The court, led by Justice John Harlan, ruled against him.

Today, Jacobson v. Massachusetts is cited as a blanket basis for virtually every vaccine mandate in modern America, but as Prof. Josh Blackman of South Texas College of Law notes, the Supreme Court decision is widely misunderstood. The Supreme Court never actually ruled on the legality of requiring citizens to undergo medical procedures, including vaccination. The decision revolved around the $5 fine. Massachusetts law did not require vaccination for resistors who paid their fines. Thus the court's ruling, for practical purposes, simply upheld Massachusetts' right to fine Jacobson. He never had to take the vaccine and the court acknowledged his right to refuse it on health grounds. But, as Prof. Blackman notes, subsequent Supreme Court decisions turned Jacobson into a blanket approval of not only vaccine mandates, but of some of America's ugliest Progressive Era policies relating to eugenics.

Vaccines and eugenics

The Progressive Era is often viewed as a time of betterment, but it went hand-in-hand with the disgrace of the eugenics movement. This movement is best encapsulated in Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger's (pictured above) "A Plan for Peace," which called for sterilization, segregation, and internment of the "tainted," including "the feebleminded, idiots, morons, insane, syphilitic, epileptic, criminal, professional prostitutes, and others in this class barred by the immigration laws of 1924." According to Nature, sections of American academia and the political class supported her vision with compulsory sterilization laws. When one 1924 Virginia law ended up before the Supreme Court, the justices invoked vaccine mandates and Jacobson v. Massachusetts in their decision.

According to law professor Josh Blackman, Buck v. Bell, which challenged Virginia's sterilization law, was upheld as fully constitutional by an 8-1 vote. Justice Oliver Holmes ruled that if states had the right to enforce vaccine mandates for the sake of public health, then why not sterilization? The practice was seen as improving America's genetic stock and weeding out the "imbeciles," notwithstanding the fact that Jacobson never allowed states to force vaccination. As a result, constitutional lawyer Robert Barnes (whose controversial client list has included Alex Jones, Kyle Rittenhouse, and Wesley Snipes) has warned vaccine mandate supporters to exercise caution with the Jacobson decision, as the mythology surrounding the case has provided the legal basis for segregation, sterilization, child labor, and general institutional racism all in the name of public safety.

Polio and the Cutter Incident of 1955

Although Jacobsen v. Massachusetts did not technically mandate vaccines, many states took subsequent SCOTUS decisions to enforce them. But surprisingly, the modern movement referred to today as "anti-vaxx" was born with a vaccine that was not mandated. In 1955, the polio vaccine hit the market. According to NPR, polio disabled around 35,000 children per year. Its most famous victim was President Franklin Roosevelt. Because of the disease's debilitating effects, NPR notes parents rushed to sign their children up for the shot when it appeared in 1953. While the polio vaccine was very effective, unfortunately, the Cutter Incident sowed doubt among Americans regarding the safety of vaccines.

According to the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, a batch of polio vaccines manufactured in a California lab in 1955 turned out to be faulty. The manufacturers had not inactivated the polio virus, resulting in thousands of children being injected with live polio. The incident paralyzed at least 200 children and killed 40. The JRSM faults the federal regulatory mechanisms, which should have caught the faulty batches before they went to market. But other than the Cutter Incident, polio vaccines correlated with a massive drop in the disease. As a result, American schools mandated it and many other shots as compulsory vaccination laws were tightened across the country.

School laws tighten

Before the 1960s, the Conversation notes that compulsory school vaccination laws were patchy and rarely enforced. Some states had no laws on the books, making it impossible for local authorities or schools to legally enforce vaccination mandates. So when measles outbreaks did not lessen despite the availability of a vaccine, many states began to tighten their school laws, where the vast majority of measles outbreaks took place.

Unlike resistance to today's covid shots, most parents supported the increasing number of vaccine mandates in the 1960s and '70s, especially as it was correlated with a massive decline in dangerous childhood diseases such as measles and polio. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act generally protected conscientious objectors, while medical exemptions were made available for children with contraindications to administration. The Conversation attributes the acceptance of mandates to a high level of public trust in the American medical establishment. This contrasts to the high level of distrust today amid the covid problem, a sentiment particularly justified among African-Americans, who have been the principal subjects of deadly medical experimentation such as the Tuskegee experiment (via CDC).

Shirking responsibility

As the number of shots required to attend school increased through the 1970s and '80s the issue of adverse reactions in children came to the fore. According to the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, pharmaceutical companies began experiencing lawsuits from angry and heartbroken parents whose children had suffered adverse reactions to their products. These litigations resulted in large financial settlements that eliminated pharmaceutical companies' incentives to create vaccines in the first place. Thus, in 1986, Congress passed the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act. This law gave pharma companies complete immunity from all civil lawsuits in cases where a mandated vaccine caused a child to die or be incapacitated. Instead, claims were now processed through a government vaccine court that set compensation. According to CNBC, however, victims of adverse events rarely obtain compensation.

This legislation is controversial. While it allows pharmaceutical companies to create and innovate with life-saving vaccines, it also provides an incentive for unscrupulous pharmaceutical companies (via the Guardian) to compromise product safety in pursuit of profit. As a result, the National Nurses United notes that big pharma has become the biggest cheerleader of vaccine mandates.

The covid-19 mandates of 2021

The United States has generally refrained from mandating universal vaccination, unlike countries such as Australia and Austria, where the unvaccinated (for covid) face harsh restrictions and even legal consequences. Generally, state and local authorities mandate covid vaccines in accordance with interpretations of Jacobson v. Massachusetts. New York City, for instance, has mandated covid shots for all workers (via CBS), while California governor Gavin Newsom has mandated them for schools. However, President Joe Biden has parted with precedent to issue a sweeping vaccine mandate on all federal employees falling under the purview of the executive branch and all businesses employing 100 people or more.

The rationale behind the mandate is simple. The CDC has found that vaccination helps reduce transmission and lessens the symptoms of covid infection. Thus, proponents such as NIAID director Anthony Fauci argue that vaccination would help end the covid problem, even if the SarsCov-2 virus is not eradicated, since the vaccines are "safe and effective." The situation, however, is more nuanced and touches a host of other concerns. According to the NY Post, these safety, regulatory, economic, and constitutional pitfalls have sent the mandate to the Supreme Court.

Opposition to the mandate

Mandate critics fall into several categories. First are critics who question covid vaccine safety standards. In addition, the BMJ found some undeclared conflicts of interest among the FDA employees and journal editors responsible for vetting covid vaccines.

There is also robust political opposition. Critics such as FOX New's White House Reporter Peter Doocy have noted that while many Americans will be required to be vaccinated to work, illegal immigrants are not. According to Reuters, migrants can sue pharmaceutical companies over adverse reactions, while under the PREP Act, Americans cannot, thus prompting the hesitation to mandate it for the former group. Connecticut capitol staffers, meanwhile, have noted the hypocrisy of state lawmakers exempting themselves from their own vaccine mandate for CT legislative employees (via NBC).

Some states, notably Florida, have openly defied the federal government. Governor Ron DeSantis has banned all state, school, and employer covid vaccine/mask mandates while charging violators $10-50,000 per employee violation. Others, such as New York, Illinois, and California, have doubled down, even as they lose jobs, businesses, and taxpayers to states like Florida and Texas (via KTLA). Regardless of the anticipated Supreme Court decision, Biden's mandate will likely further highlight the partisan and geographic divisions within America that have been increasingly visible since the 2016 election.