False Facts That Actually Changed The World

Look back through our history, and you'll find that the idea of fake news definitely isn't new. In fact, there's a ton of theories, stories, and scientific "facts" that we now know just aren't true. Making matters worse, some of those facts weren't simply accepted as truth, but were used as the very building blocks of the world we know today ... for better or worse. Usually worse.

We thought nature was endless, and now things are extinct

Drive across the US today, and it's no big deal. There's highways and rest stops as far as the eye can see, but just imagine what it must have been like a few centuries ago. Vast herds of buffalo, flocks of thousands of birds, dense forests ... paradise on earth? Absolutely, until mankind came along and ruined the heck out of it.

What New World settlers found was so incredible that they developed what the British Association for American Studies calls the "myth of superabundance": a belief that this unsettled world was limitless, and that there were so many resources that there was no reason to think we'd ever use them all up. We began making decisions based on that principle right from the moment we set foot on the East Coast, when we decimated beaver, elk, lynx, and bear populations, and completely wiped out the passenger pigeon.

Obviously the myth of superabundance couldn't be less true. And spoiler alert: we used everything up. Even as the promise of wealth and limitless natural resources drove people west, the National Park Service says that loggers destroyed entire forests, bison were hunted from a population of around 60 million down to about a thousand, elk and beaver were poached relentlessly, and herds of livestock destroyed wild grasslands. Preservationists fought against those practices, and they had an uphill battle. Fortunately, they persevered — somewhat — and it's why we have national parks and protected areas today.

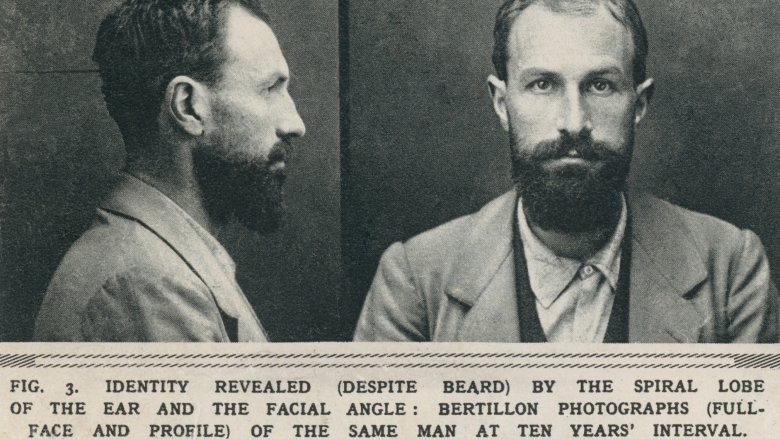

We thought we could read a person's character by their appearance, and it's made us superficial jerks

We do it all the time, whether we know it or not. It's the reason actors like Jason Statham have a job always playing the same type of character — because we think we know what kind of person he is by the way he looks. That's the basic idea of physiognomy. The Iris, the official blog of the Getty Arts Foundation, says that physiognomy has its roots in the ancient world. Pythagoras was known for rejecting students if they didn't look smart, and Aristotle wrote that people with broad faces were dumb ... making even ancient brainiacs superficial jerks.

It wasn't until Giambattista della Porta's 17th century writings that the concepts of physiognomy were concretely defined, and it's still why we call people "low-brow" or "stuck-up." A Wired article says the scientific community largely called the whole thing bunk by the end of the 1600s. But that didn't stop physiognomy from lingering on in various dangerous forms for a few more centuries.

According to that same Wired article, it was Cesare Lombroso who really did some serious, stupid damage. He was a criminologist writing in the 19th century, and he firmly believed that the world's criminal element could be identified at a glance. How? By their ape-like appearance, their vestigial tails (you read that right), and their tattoos. So thanks, Mr. Lombroso, for reinforcing the horrible idea that you can and should totally judge a person based on appearance.

We thought smells made you sick, so we cleaned up the wrong things

You wouldn't want to have lived in 19th century London. In the 1830s, epidemics of typhoid, influenza, and particularly cholera decimated the city. According to London's Science Museum, it was so bad that even the upper class started to sit up and take notice of the squalor that the city's poor were living in. Behind it all was the miasma theory of disease transmission, which basically meant that it was the bad-smelling air that was making people sick and dead. That was completely wrong, of course. But this misunderstanding actually had an incredibly positive impact on the world as a whole.

The miasma theory led London to make improvements in sanitation, drainage, and ventilation, and that's important stuff for a civilized society. It didn't happen overnight — 1858 was the year of the Great Stink, and we'll leave that to your imagination — but there was still a problem. After the cleanup, people wouldn't accept that bad smells didn't make you sick.

In the 1850s, an anaesthetist named John Snow theorized that the cholera that killed so many citizens wasn't a stink, but actually a water-borne contagion. But the miasma theory was so widely accepted that no one believed him. He died in 1858, and people were still stamping their feet and firmly insisting that it was the air.

The miasma theory hung in there until 1892, and according to Buckinghamshire Chilterns University College lecturer Stephen Halliday, it wasn't until a cholera outbreak in Hamburg, Germany, didn't spread to London — in spite of London's still-somewhat stinky air — that people started thinking that maybe Snow had been onto something after all.

We believed in a magical, Christian kingdom, so European conquerors ran amok in Asia and Africa

In 1145, rumors of a mysterious Christian kingdom started circulating through Europe, and you would totally want to live there, too. According to ThoughtCo., the legend said that the kingdom was ruled by the good Christian king Prester John. There was no crime and no vice, there was plenty of food, the rivers flowed with gold, and it was the site of the Fountain of Youth. Global Middle Ages says it was called the richest kingdom in the world, filled with jewels, natural resources, and spices.

There was a problem in paradise, though: the kingdom was surrounded by all kinds of heathens and savages who wanted nothing more to plunder it ... which was, presumably, not at all why Europeans had set their sights on paradise.

No one was exactly sure where Prester John's kingdom was, and there were plenty of expeditions sent to find it. One of the early ones was dispatched by Pope Alexander III, who hoped to defend the kingdom against the infidels. Later expeditions mapped huge patches of Asia and India in hopes of stumbling across the beleaguered king.

When explorers determined that the kingdom wasn't in Asia, they set their sights on Africa. According to Black Past, the legend of Prester John was the driving force behind Italy and Portugal's 15th century forays into Ethiopia and opening Africa to European exploration. We don't really need to discuss the consequences of how Europe's trips through Africa turned out, since society continues to deal with their repercussions every day.

We thought phlogiston was a thing, so someone invented chemistry

Chemistry is a fairly new science, invented in the 1770s. You could argue it only happened because one scientist was annoyed at a flimsy theory that attempted to explain a whole lot of everything.

According to MEL Science, Johann Joachim Becher was the first to come up with a theoretical substance he called terra pinguis. George Ernst Stahl gave it a name that became more popular — phlogiston — but it was essentially burning. The theory said this substance was contained in all things that burned and was released by the process of burning. Things that burn easily had a lot of phlogiston, and when it was gone, burning stopped. When the air absorbed too much of the substance it became phlogisticated and wouldn't allow anything else to burn.

Sounds reasonable enough, right? The theory stood for about a century, until French scientist Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier decided to call bullgiston. He was the first to really sit down and have a long chat with phlogiston about all the reactions it couldn't explain, and decided to come up with his own theories of combustion that actually worked. The American Chemical Society credits him with being the first to describe oxygen and for laying out a series of guidelines for the new science of chemistry, all so something like this phlogiston nonsense wouldn't happen again and delay knowledge another century or so.

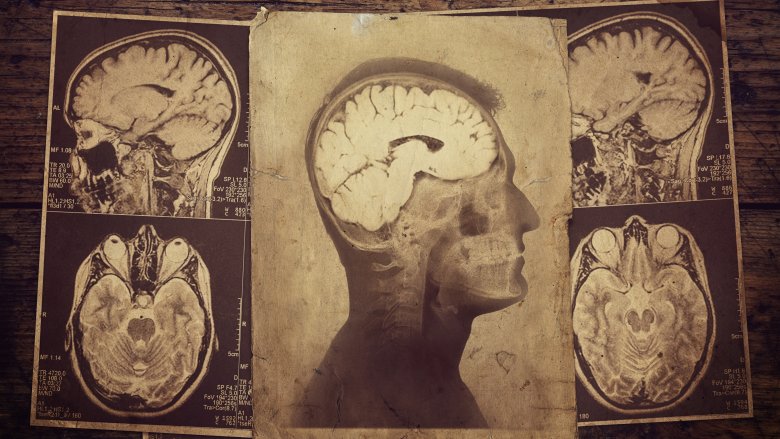

We thought the body was governed by four forces, so that's how we kept trying to heal it

London's Science Museum blames the ancient Greek physicians for writing the long-accepted treatise on exactly how humans' innards and squishy bits worked. They're the ones who said the human body was governed by the interaction between four humors: yellow bile, black bile, phlegm, and blood. That disgusting quartet was associated with the earthly elements of fire, earth, water, and air, and the Harvard University Library's collection on contagion says that they were also linked to the human conditions of choleric, melancholic, phlegmatic, and sanguine, respectively. When those humors were in balance, all was well. But when they were unbalanced, we got sick.

It has its own weird sort of logic, and it's not entirely surprising that it was the go-to theory in medicine well into the 19th century. A lot of medical treatments — like enemas, purging, and lifestyle changes — were thought to restore the humors' balance. One of the most dangerous of these practices was bloodletting, and it continued well into the middle of the 19th century. It was definitely a case of the treatment being worse than the illness, and countless people died from what was being done to, theoretically, make them better.

PBS NewsHour says that one of those people, in fact, was George Washington. While we don't know precisely what killed him, the fact that doctors removed about 40 percent of his blood in an attempt to alleviate his sore throat and difficulty breathing probably didn't help matters in the least.

We thought we could discover an immortality elixir, but we invented a more efficient killer instead

Early Chinese texts described elixirs that could do everything from turning a mortal man into a divine being, to making you invisible. Some elixirs would let you enter the world of the immortals, where demons and the Jade Women would serve your every need. Find a person who says they don't want to sign up for that retirement plan, and you'll find a person whose pants are very definitely on fire.

Needless to say, alchemy was serious stuff back in the day. People spent lifetimes trying to create these elixirs, and in 850, a Tang Dynasty alchemist created a formula that was 75 parts saltpeter, 15 parts charcoal, and 10 parts sulfur. ThoughtCo. says that while it didn't make him immortal, it did something else important. A contemporary text notes that "smoke and flames result, so that [the alchemists'] hands and faces have been burnt, and even the whole house where they were working burned down."

That's because that formula isn't for an Elixir of Life — it's for gunpowder. In what might be the biggest bit of irony in history, alchemists didn't create life, they created something that would revolutionize warfare very nearly from that day forward. Their creation was weaponized by 904, when the Song military used it to bring the opposite of life to the Mongols.

We thought sight was based on invisible eye-beams, and it shaped world superstitions

We've always been vaguely aware of the fact that our eyeballs process the information from the world around us and make brain-pictures, but we're historically iffy on mechanics. According to ancient Greek scientists, our eyes worked because they contained some kind of fire that streamed out from our faces and scanned the world around us, sort of like a benign version of the X-Men's Cyclops. Charles G. Gross's article in The Neuroscientist says that the theory was accepted as science for a long time, and that it started one of world's most widespread superstitions: the evil eye.

Gross says that belief in the evil eye and the idea that we can feel someone looking at us is rooted in the idea of extramission vision, and the concept of the evil eye is found in a huge number of cultures and religions. It spans Islam, Judaism and Christianity, it's repeated from Eastern Europe to America. Cultures have their own charms and wards against the evil eye, and it's always a curse, and it's always the act of looking that causes it. It causes everything from bad luck and illness to natural disasters, and we still ward ourselves against it in the 21st century. So stop staring. It really is impolite.

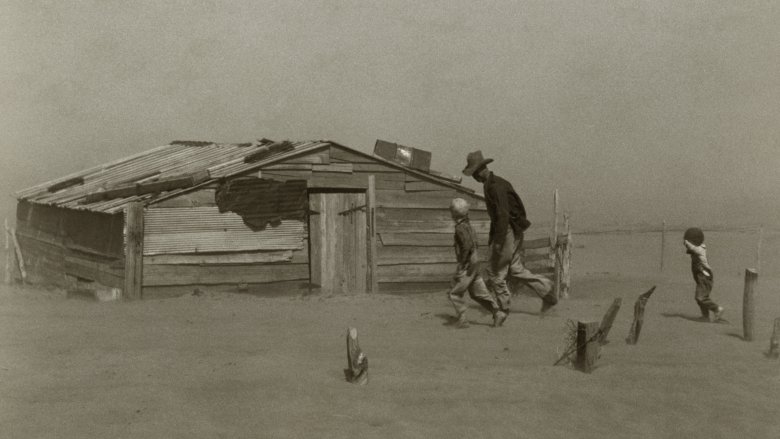

We thought the more we farmed the more it would rain, so we caused the Dust Bowl

You've seen the pictures of the American Midwest at the turn of the 20th century, and there's a lot of dry, dusty land there. There's a weird reason that happened, and it started at the end of the Civil War as people started moving to the Midwest and settling down to a new life.

Wired explains that, between 1865 and 1875, people started believing that more farming would bring more rains. "The rain follows the plow" became the mantra of the Great Plains, and it was spread by everyone from journalists and scientists to politicians and railway barons who stood to make a fortune off of people heading west. Even the Smithsonian Institution produced publications on how planting trees and building railroads would make the rains come.

Not only did the promise of bountiful lands drive settlement in the Midwest, but it also created the devastating Dust Bowl and dirt storms of the 1930s. According to the University of Illinois, it was when farmers kept farming through drought conditions that they stripped away ground cover and turned the Midwest into the exact opposite of a rainy, farm-friendly paradise.

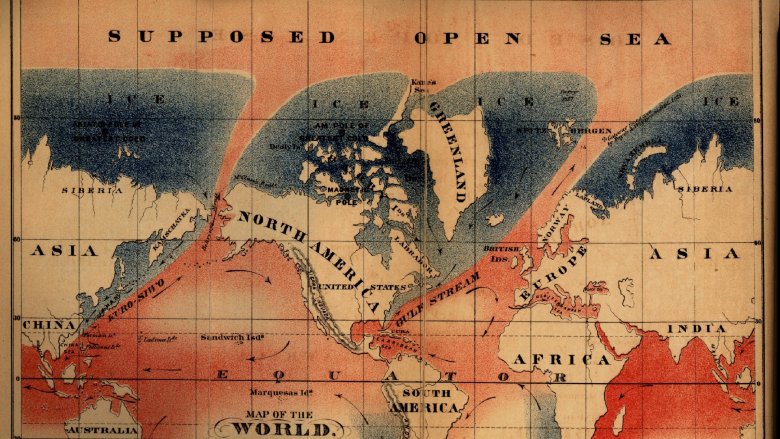

We believed in an Eden at the North Pole, so we explored the Arctic

In our age of Google Earth, it's hard to imagine not knowing what's lurking in every corner of the globe. But it wasn't really that long ago that we didn't have the foggiest idea what was at the North and South Poles, and imagination can be a dangerous thing.

In the 16th century, explorers told some pretty tall tales about what they believed was at the North Pole: a warm, open sea, as explained by io9. One major part of the theory claimed that the region's endless days would be enough to melt any ice that might have been there. Another aspect of the theory postulated that since massive ice floes could only happen in freshwater anyway, there wouldn't be any in the Arctic. That meant sailing straight across the pole would be something of a shortcut, and intrepid explorers spent the next few hundred years trying to do just that.

It was as late as the 1850s that explorers were coming back with bits and pieces of information that seemed to lend credence to the idea that there really was an open ocean at the North Pole. It was only in 1879 that it was confirmed that no, there was no open ocean there. Those hopes finally ended with the ill-fated expedition of George Washington de Long.

In an ironic twist, however, we might just be making this legend come true after all.

We blamed all Jews for crucifying Jesus, and invented Antisemitism

People do horrible things in the name of religion, and according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, hatred against the world's Jewish community started thanks to a falsehood written into Christian doctrine by early church leaders. It was the claim every Jewish person had a personal responsibility when it came to Christ's crucifixion, and their continued suffering was punishment for past acts and for holding onto their faith.

It only got more horrible as other accusations masquerading as facts were piled on the hate-fire. By the 10th and 11th centuries, Europe wholeheartedly embraced the idea that other religions were a direct threat to Christianity, and hate escalated into "blood libel." According to popular belief (via Moment), blood libel was a practice in which Jews killed Christian children, drained their blood, then used it either for ritual purposes, for baking, or for replenishing their own fluids. It was reported as absolute and undeniable fact. Cases date to 1144, when English Jews were accused of torturing and killing a boy named William. Jews in Italy were accused of killing a little boy named Simon in 1475, ultimately sentenced to death. Meanwhile, Simon was canonized, with the sacrifice as part of his backstory.

Blood libel is still a thing, and trials have been held from Russia to New York into the 20th century. And we all know what happened during World War II.

We believed we're a complete product of our genetics, and invented eugenics

According to Garland Allan, a biology professor at Washington University in St. Louis, when we started talking about biological determinism in the 18th century, it promoted the idea that we inherited everything we are from our parents. Beyond height and hair color, proponents believed personality, criminal tendencies, and even laziness had more to do with our genetics than our environment or other external forces. It's a dangerous way to think, and by the late 1800s naturalist Francis Galton was talking about eugenics and selective breeding as a way to encourage the inheritance of good traits and ultimately, the creation of a more perfect race of humans. You can see where this is going.

Galton published Hereditary Genius in 1869, preaching that smart people were biologically superior to the world's slackers. According to genetics writer David Shenk, the world didn't look back.

The Third Reich had one of the most notorious eugenics programs, but other countries did it, too. The U.S. introduced sterilization legislation in the 1920s and more than half the states established their own involuntary programs. They were largely based on IQ tests that ranked people on a scale from (not making this up) "normal to high-grade moron." It wasn't until the 1970s the public found out thousands of people had been sterilized, all in the name of a bogus scientific theory (via Britannica).

The world didn't end in 1844, so we founded new religions

Details are good but being too specific can be dangerous. That's exactly what William Miller discovered on October 22, 1844. He had preached as fact that Christ would be returning to Earth that day, and according to Grace Communion International, somewhere in the neighborhood of 100,000 people gathered to see the spectacle of the Second Coming. Night fell, and no one came. Miller's fact had been proved not-so-factual in a spectacular way that the religious community later called The Great Disappointment.

The Adventist News Network says the revelation was hugely out of the ordinary for the belief system at the time. While most believed the Second Coming was a figurative thing, Miller kick-started a belief — and hope — in the actual, real, physical return of Jesus. After the Second Coming didn't happen on the proclaimed date, Millerites debated about what it meant and formed entirely new religions based on the failed prophecy. The Jehovah's Witnesses started from one branch of the group, and so did the Seventh-day Adventists. They believed the date was significant but Miller had gotten the event wrong, instead choosing to make that the day of the final phase of Christ's heavenly ministry. Miller may not have predicted the end of the world correctly, but he did launch a few religious movements — not an insignificant legacy.

We believed in external influences on a woman's baby, so we legitimized the idea of virgin births and racial purity

Let's start with the idea of maternal impressions, the ancient theory suggesting anything a pregnant woman thinks of or looks at will impact her baby. Don't laugh — we thought that way until the 20th century. There's also something called telegony, which basically says a child is influenced by its mother's previous sexual partners on a biological level.

Those two things helped shape the way we see a child who might not seem like they completely belong to their "parents." The Daily Beast recounts the story of Madeleine d'Auvermont, who gave birth in 1637 — four years after her husband left town. At her adultery trial she proclaimed innocence, saying she had just thought really, really hard about her husband the night her son was conceived, and a miracle happened. It worked, and the child was officially made the cuckolded husband's heir. It's also how women have successfully explained away giving birth when they were supposedly virgins, or bearing children that are clearly a different race than themselves or their husband.

It also helped establish Nazi doctrine about racial purity. Since telegony was still a thing during the Third Reich, women who had already had relations with someone of an "inferior race" were deemed racially impure. The only way to get rid of the bad was to get rid of it completely — even Darwin said as much (via The American Scientific Affiliation). Thanks, Darwin.

We thought we could change nature by force of will, so we ruined a region's agriculture

In 1936, Trofim Lysenko presented the bizarre theory of Lysenkoism to the Conference of the Lenin Academy in Moscow. The idea completely undermined all the previous work done by geneticist Nikolai Vavilov (who promoted things like crop diversity and breeding crops by selecting desirable traits). Lysenko offered up the completely nutty theory that any crop could be made to be made to thrive in any environment just by exposing it to that environment over successive generations, and the Soviets loved it. It was what they were trying to do to their citizens, after all, and even as Vavilov's absolutely correct theory was pushed aside (and he starved to death in a Soviet prison), Lysenkoism became the agricultural system of choice.

The Conversation says that lasted into the 1960s, giving it plenty of time to do some serious damage. Soviet farmers were taught one plant would sacrifice itself for the good of its neighbors, that they chose their reproductive partners, and they'd get used to those cold Russian winters.

They didn't. According to the Smithsonian, it pretty much ended the advancement of Soviet agriculture and biology, kicked off a series of food shortages, famines, and crop failures, and left actual scientists imprisoned, dead, or simply gone. Lysenko essentially told Soviet leaders what they wanted to hear and stopped science for decades.

We thought there were different species of man, so we made slavery totally cool

Slavery has been a thing since the earliest days of man, and it's sort of like one of those Magic Eye posters. Every time you look at it a little bit differently, you see something that's a slightly different kind of awful. Those who believed in it and practiced it needed to keep finding ways to convince themselves it was all right, and in the 19th century, one of those ways was the idea of polygenism.

According to Pittsburg State University's Robert A. Smith, it was Dr. Charles Caldwell who popularized the idea that humanity had several different origin points. He was writing in the 1830s when he came up with the theory of different races originating in different places, and by the time JC Nott and George Gliddon wrote Types of Man, that turned into the idea there were different species within mankind. Nott went as far as talking about "hybrid" offspring, saying these people were occasionally fertile and proposed nature had come up a system that "permitted the gradual extinction of hybrid races." So he took a crack at offending pretty much everyone and also reinterpreted history through an unthinkably racist lens — certain people loved it.

He wasn't the only one saying it, either. Louis Agassiz, a Harvard professor, wrote about his observations on how different races were, and polygenism successfully went on to be the rallying cry for anyone looking for a handy excuse to justify slavery.

We were sure there was a whole city made of gold in South America, so we destroyed entire civilizations

The stories of a city of gold hidden somewhere deep in the South American jungles started in 1519 with Cortes, his capture of Montezuma, and his complete destruction of the Aztecs. As if that's not bad enough, the story about Cortes's ill-gotten fortune in gold and silver started making the rounds throughout Europe, and according to Thought Co, those stories came together to form the legend of El Dorado.

You noticed how it's called a legend, right? Thousands and thousands of people heard it as a true story, setting off to South America to look for the lost city of gold and doing a huge amount of damage along the way. In 1537, Spanish conquistadors massacred the Muisca peoples and dredged Lake Guatavita, the lake associated with earlier tales of El Dorado and their gold-clad king. When they didn't find enough gold, they kept looking. In attempts to get leads on where the city was, native people were captured, tortured, and enslaved. It's also largely why European explorers mapped so much of South America, but that's a small consolation. If that's the only good that came of it, we could have waited for satellites.

Freud preached everyone was born bisexual, so we tried 'curing' sexuality

The possibility that homosexuality could be cured was a huge debate in the 1980s and 1990s, and according to The Atlantic, it wasn't until President Obama that there was a call to ban conversion therapy. The Atlantic also says it was in the 19th century that being gay shifted into classification as a mental health issue instead of an issue of sin. That shift started thanks largely to Sigmund Freud, who famously wrote about his belief everyone was born bisexual and would "move along a continuum of sexuality" that would change and shape their desires.

It was a dangerous idea he preached, and it started movements to "cure" homosexuality through various therapies. It was mainstream science, too — in 1965, Time even ran an article reporting on the success one University of Pennsylvania psychiatrist had in rehabilitating his gay patients. The idea was the norm, and by the 1960s and '70s, psychiatrists were using everything from aversion therapy to electroshock treatments to try to "fix" people.

Strangely, even though Freud may have kick-started the belief that being gay was something that could be treated, he didn't advocate it. He wrote it wasn't a mental illness — even though it got turned into one — and there was no reason to cure it, proving how dangerous it can be when you don't read all the way to the end of an article.