The History Of Britain's My Lai Explained

When news broke in 1969 about the United States' massacre of unarmed civilians in Mỹ Lai during the Vietnam War, people in the United Kingdom questioned whether or not the British army could ever be capable of such a travesty. Although many insisted that British troops could never commit such a crime, they would soon learn exactly how wrong they were, straight from the horse's mouth.

The massacre at Batang Kali committed by British troops soon became known as Britain's Mỹ Lai and there are numerous incidents, which occurred during the Malayan Emergency, that bring up parallels to the Vietnam War. But unlike the Vietnam war, the Malayan Emergency ended with a victory for the colonizing forces.

Britain's Mỹ Lai may have been the only mass execution of unarmed civilians during the Malayan Emergency, but it's just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the horrors perpetrated during the war between the Malayan National Liberation Army and the British Empire. This is the history of Britain's Mỹ Lai explained.

A brief history of British Malaya

The British Empire first began colonizing Malayan territory in 1786, beginning first with the island of Penang. In 1819, Singapore was also occupied and by 1825, the British also annexed Malacca away from the Dutch. According to The Developing Economies, these three colonies would later become the Straits Settlements. But Britain didn't start exerting control over the Malay states until the 1870s, when the Straits Settlements were made into protectorates of the British Empire.

In Spaces of Occupation, David Baillargeon writes that although the Straits Settlements were absorbed by the crown, most of the Malay Peninsula "remained officially independent from foreign control until around the turn of the twentieth century." Instead, they existed as the Federated Malay States (FMS), which included Negri Sembilan and Selangor, and the Unfederated Malay States (UFMS), which included Johor and Terengganu. And official independence didn't translate to actual independence. While the Straits Settlements were controlled by the British colonial government through direct rule, the FMS and UFMS were kept under indirect rule despite remaining separate political units.

In this way, British Malaya was simply "a convenient British administrative and geographic term," Boon Kheng Cheah and Cheah Boon Kheng write in "Red Star Over Malaya," to describe these states. In 1946, they were all amalgamated into the Malayan Union, which was replaced with the Federation of Malaya two years later.

Strikes in Singapore and Malaya

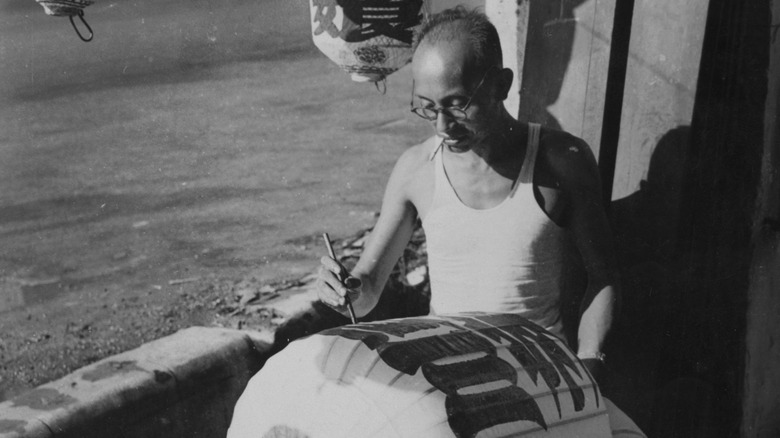

The first general strike in Singapore occurred in January 1946, but there were numerous strikes starting in October 1945 that intended to "pressure and embarrass" the British colonial administration. Organized by the General Labor Union (GLU), the general strike was supported by over 173,000 workers and brought the economy to a standstill.

The British government was convinced that the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) was responsible for the strikes and although the strikes were meant to be an "anti-colonial struggle on the labor front," the strikes were "instigated as much from below as above," according to The Historical Journal. The workers of Singapore were united by economic issues such as "low wages and shortages of essential commodities" and some of the strikes, like the Wharf Workers' Union strike of 1946, called for material demands as well as a "right to a dignified life."

But the 2-day general strike that began January 29, 1946 was a little different. Rather than demanding material gains, the general strike called for the release of Soong Kwong, secretary-general of the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army, as well as several members of labor unions who'd been arrested. In "A History of Modern Singapore," C.M. Turnbull writes that although the government released Khwong, the following month they went on to arrest 27 more people. Ten were subsequently "banished without trial." But strikes continued throughout 1946, resulting in almost 2 million lost man-days in Singapore and Malaya.

The Sungai Siput incident

The first shots of the Malayan Emergency are said to have been fired in the Sungai Siput incident. Although the MCP was considering launching an armed struggle against the British and had agreed to do so in March 1948, according to "Southeast Asia's Cold War" by Cheng Guan Ang, there was still debate over when to begin the armed struggle. So when the Sungai Siput incident occurred, it was carried out by "communist comrades without the concurrence of their superiors," effectively starting the armed struggle before wider preparations were complete.

On June 16, 1948, three British rubber plantation managers at the Elphil estate and Phin Soon estate, A.E. Walker, J.M. Allison, and Ian Christian, were murdered in the Sungai Siput district. In "My Side of History," Chin Peng, who was the leader of the MCP at the time, writes that although he wasn't aware of the murder plot and ultimately regretted Christian's death, Walker and Allison reportedly had "histories of imposing harsh and bullying treatment on the workers who had no legal redress and no way of achieving any form of justice other than through strike action."

Two days after the murders, a State of Emergency was declared in Malaya, the MCP was banned, and Sir Edward Gent, the High Commissioner to the Federation of Malaya, declared that the illegal possession of arms and explosives was now subject to the death penalty, per The Kalgoorlie Miner.

What was the Malayan Emergency?

The Malayan Emergency, also known as the Anti-British National Liberation War, was used to refer to the fighting in southeast Asia between the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA) and the British empire over Malaya's independence. The Malayan Emergency would ultimately last until 1960. And the use of the word "emergency" rather than "war" on the part of the British was a deliberate choice made in response to London insurance policies.

According to "British Concentration Camps" by Simon Webb, all of the British-owned plantations and tin-mined were insured by British companies and many of them had "clauses which exclude payment for damage during a war." But because the insurance companies would still be forced to cover losses during "civil disorders and riots," Malaya became a literal war-zone in everything but name so British owners wouldn't have to suffer any financial losses. British insurance companies had reportedly withdrawn coverage in Palestine in 1945 and 1948 and were "threatening to do the same in Malaya." And at the end of the day, the Palestinian comparison wasn't lost on the British, who brought in "several hundred British sergeants" into Malaya after the demobilization of the Palestine Police Force, V. Suryanarayan writes in The Revolt that Failed.

In "Small Wars, Faraway Places," Michael Burleigh also writes Emergency Powers were instituted instead of martial law in order to maintain this distinction for insurance purposes.

What was the MNLA?

The MNLA was formed out of the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army, which was created during the Second World War when Malaya was under Japanese occupation. And World War II ended and British colonial rule was restored, the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army stood down and the MCP rose in its stead, according to the Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. But after the MCP was banned during the beginning of the Malayan Emergency, it reformed into the Malayan Peoples' Anti-British Army, which was renamed the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA) in 1949.

The University of Cambridge also notes that although the majority of those involved in the MNLA were Chinese, the Tenth Regiment of the guerrilla army was the "only Malay-majority regiment" of the MNLA. Formed by Cik Dat bin Anjang Abdullah, also known as CD Abdullah, the 10th Regiment amassed up to 500 Malay recruits by the early 1950s. Abdullah was "the most senior Malay leader" of the MCP and the subsequent MNLA, according to "The Malayan Emergency" by Souchou Yao, and would go on to become the Chairman of the Malayan Communist Party in 1988.

And according to "The Shaping of Malaysia" by Amarjit Kaur and Ian Metcalfe, the disparity in the numbers of Chinese MNLA and Malaya MNLA members may have been caused by the fact that by the 1930s, workers from Chinese and Indian outnumbered Malayans in British Malaya, with one-third of Chinese people and one-fourth of Indian people in British Malaya being local-born.

Raids on the colonial government

The MNLA primarily targeted rubber plantations, although they also occasionally raided isolated police stations as well, like during the Bukit Kepong incident. And during the first few years of the Malayan Emergency, they were largely successful. According to "Small Wars, Faraway Places," the MNLA was indiscriminate in the rubber plantations they targeted, which ranged from massive 14,000-acre plantations owned by London-based firms to smaller 1,000-acre plantations with an "absentee Chinese [owner]." However, they did generally avoid American mining operations, mostly due to the fact that "they were formidably well armed."

By October 1951, over 1,000 British and Malayan troops and almost 2,000 civilians had been killed. Up to 500 civilians were reportedly abducted by the MNLA as well, writes HistoryNet. And many places, like the Kajang area, faced violence from both the MNLA and the British colonial government, Karl Hack writes in The Malayan Emergency. And because the MNLA often established themselves close to villages, the government response "contributed to excess killings from the government side."

The lowest moment for the British colonial government came on October 6, 1951, when the MNLA ambushed and killed Malayan High Commissioner Sir Henry Gurney. The following year, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill appointed Sir Gerald Templer as the new Malayan High Commissioner and Templar set out to do everything in his power to weaken and suppress the MNLA. But the British policy of violent destruction actually began well before 1952.

The British Mỹ Lai

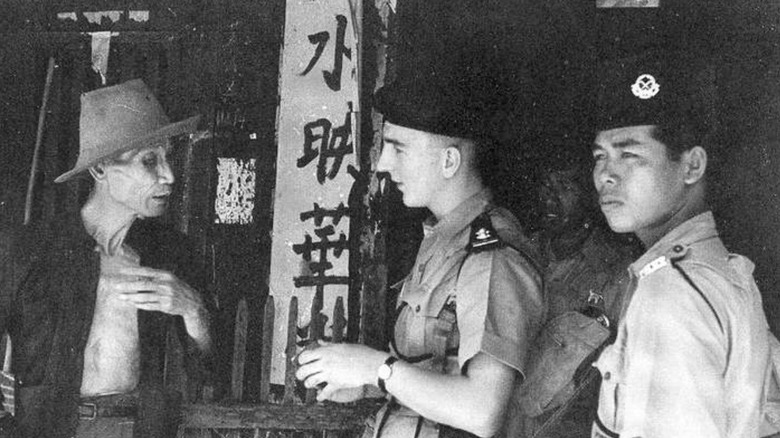

On December 11, 1948, 14 men from the 7th Platoon, led by Sergeant Charles Douglas and Sergeant Thomas Hughes, entered Batang Kali, a small settlement that was part of the Seungei Remok rubber plantation in the Selangor state. The village was filled with unarmed civilians and by the time the platoon left the following day, 24 men had been killed and all the homes were burned. In "The Malayan Emergency," Yao writes that one man was able to survive by pretending to be dead. The rest of the survivors fled the village and when they returned several days later, they found "the decomposing bodies of their husbands, brothers, and sons," writes Griffith Review.

The villagers were questioned about aiding the MNLA and although the official statement of the soldiers claimed that the villagers tried to make a "mass escape in the jungle," at least one soldier claimed they knew beforehand that the villagers were going to be murdered. Another soldier said that "we were told before going in to tell the same story, that is that the bandits were running away when they were shot."

Known as the Batang Kali massacre, the incident has also been referred to as "Britain's Mỹ Lai," per "Massacre in Malaya" by Christopher Hale, a reference to the American slaughter of Vietnamese villagers in Mỹ Lai in 1968 during the Vietnam War. Although there was an official investigation in 1948, it exonerated the soldiers without interviewing any of the surviving witnesses.

Regulation 27A

One month after the Batang Kali massacre, Chief Secretary of the Federation of Malaya Sir Alec Newboult passed Regulation 27A in January 1949. This regulation authorized "the use of lethal weapons [to] prevent the escape from arrest, so long as a warning war first issued," per "The Malayan Emergency." The Guardian also notes that the regulation also claimed that anything "done before the coming into force of this regulation" was still covered by Regulation 27A. This effectively made the Batang Kali massacre lawful.

And the massacre is believed to have been as deliberate as the subsequent regulation absolving its participants. Attorney General Sir Stafford Foster Sutton, who was in charge of the 1948 investigation, even privately stated that "there was something to be said for public executions as a legitimate means to demoralize those involved in the insurgency," per "The British Way in Counter-Insurgency" by David French. And unfortunately, many of the original testimonies of the soldiers involved in the massacre have been lost by the British government, likely destroyed along with thousands of other documents relating to British colonialism.

Meanwhile, the Batang Kali massacre was considered a victory against the MNLA, despite the fact that Chin Peng claimed that the village was never linked to the MNLA.

Trying to starve the MNLA

Under Templer, the British colonial government in Malaya also tried a number of tactics to starve the MNLA, instituting what's known as a "scorched earth policy," similar to what the British had done during World War II when the Japanese occupied Malaya. The New York Times writes that the British destroyed any crops that they believed would be used to feed members and supporters of the MNLA. This was most effectively done with the use of herbicides sprayed from British planes, which not only destroyed crops but also "strip[ped] trees bare and deprive[d] communist guerrillas of cover."

New Scientist writes that the British government used herbicides containing dioxin, creating a defoliant "virtually identical to Agent Orange" known as Trioxone. The Imperial Chemical Industries also reportedly worked closely with the British government on the implementation of the herbicides

Large-scale testing of herbicide spraying began in February 1952, and although it was recommended to cut the vegetation by hand, by March 1953, crop spraying began via helicopters. According to "Imperial Endgame" by B. Grob-Fitzgibbon, it was said to have an "added advantage of making the ground 'completely sterile' for at least a year if applied at the greater density of 40 pounds per acre." Although the British government claimed at the time that the herbicides used "all share the property of being harmless," even small amounts of dioxin can cause chloracne, cancer, and congenital issues in embryos.

British war crimes in Malaya

The Batang Kali massacre and the spraying of herbicides weren't the only war crimes committed by the British during the Anti–British National Liberation War. And although the Batang Kali massacre is the only recorded incident of a mass killing of civilians by the British, it's estimated that in total, over 1,000 civilians and up to 13,000 MNLA members and supporters were killed by British colonial troops during the Malayan Emergency, according to "British Counterinsurgency" by Herbert Ekwe-Ekwe. Thousands were also deported.

In "Dark Trophies," Simon Harrison writes that the practice of decapitating people and posing with the severed heads was common practice among the British troops in Malaya. But after The Daily Worker published pictures of the practice, the British government decided that "the risks of handing the enemy a propaganda advantage outweighed the benefits," it was technically banned around the end of 1952.

And as the Emergency Powers allowed for arbitrary detentions, thousands were imprisoned and violently interrogated about the MNLA. In The Other Forgotten War, Christi Siver writes that the police in Malaya, including those transferred from Palestine, "used torture to try to gain information on insurgent locations and operations."

During this time, the Geneva Conventions were also being negotiated, with the original treaties being finalized in 1949. And although the British "never explicitly stated their intent to comply with the Geneva Conventions" during the Malayan Emergency, they did draft pamphlets to inform troops about their "legal obligations under the treaty."

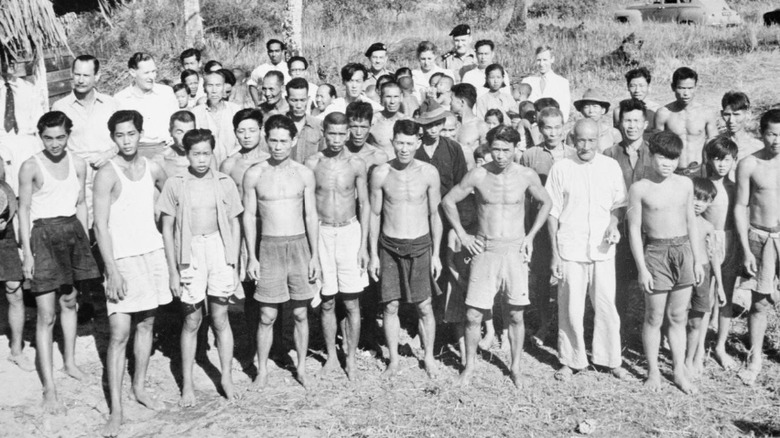

The Briggs Plan

During the Malayan Emergency, the British also executed the Briggs Plan in 1950, created and named after Lieutenant-General Sir Harold Briggs. In "British Concentration Camps," Webb writes that Briggs believed the MNLA was being materially supported and being given intelligence by the "half-million or so Chinese villagers who were scattered along the edges of the jungle." Thus, it would only be by removing these people and keeping them under close watch that the British could deprive the MNLA of food and information, despite the fact that such actions were now explicitly forbidden by the Geneva Conventions.

According to "The Malayan Emergency," the relocation of civilians began as early as 1948, with people resettled in camps surrounded by "barbed wire fences and watchtowers" and police patrols. But the Briggs Plan "expanded the scale of resettlement."

As the colonial police set fire to hundreds of villages, those displaced were forced to go live in military concentration camps, though they were called rehabilitation camps, created "for the purpose of denying a foothold to guerrilla squads in the forest areas," according to "Telangana People's Struggle and Its Lessons" by Puccalapalli Sundarayya and Harindranath Chattopadhyaya. By the end of March 1952, 11,000 "suspected terrorists" were being held in camps and 120,000 civilians were displaced into concentration camps. "Another 3-400,000 were to follow." Thousands of Orang Asli were also detained in concentration camps.

The British public learns of the massacre

At the time, the majority of the British public knew little of the atrocities being committed in Malaya and the Batang Kali massacre was completely unknown. But in December 1969, the Batang Kali massacre was finally publicly revealed by a former National Serviceman called William Cootes. According to History Today, Cootes gave an interview to The People, the British Sunday newspaper, admitting that he'd been part of the Platoon that had massacred Batang Kali and that his commanding officer, George Ramsay, had given them instructions to "wipe out anybody they found there."

Cootes was reportedly inspired to make this confession because of journalist Seymour Hersh's reporting on the Mỹ Lai massacre, which many in Britain had responded to by claiming that British troops would never be "capable of committing such an atrocity." Alan Tuppen would also later testify that they were told "to wipe out a particular village and everyone in it because, he said, they were either terrorists themselves or were helping terrorists in that area."

The British government subsequently referred the incident to the Department of Public Prosecutions, but according to "Massacre in Malaya," Attorney General Sir Peter Rawlinson terminated the investigation in June 1970 "with a view to upholding the good name of the army." In 1992, the BBC documentary "In Cold Blood" once more brought the massacre to the British public's attention.

Rulings by the UK courts

Over the years, there were numerous calls to the British government by survivors and relatives of those killed to hold a public investigation into the Batang Kali massacre. But the British government has repeatedly refused and even when the Royal Malaysia Police attempted to investigate between 1993 and 1997, the United Kingdom gave "virtually no assistance" and had an "uncooperative attitude," BBC reports.

Led by Nyok Keyu Chong, the families of the massacred appealed to the British government in 2012, but London's High Court upheld a previous decision not to hold a public hearing. And although this was appealed to the United Kingdom Supreme Court in 2015, the U.K. Supreme Court declared that the government isn't obliged to investigate because the massacre occurred "more than 10 years before the critical date when the right of petition to the Strasbourg court was recognized by the U.K. and created a duty to investigate," according to The Guardian. However, Lord David Neuberger did acknowledge that the murders were "unlawful."

The Conversation writes that the families also applied to the European Court of Human Rights in 2016, but their application was rejected two years later.