The Untold Truth Of The Crow Tribe

The new show "1883" features an elder who aids the main characters, the Dutton family, in their trek westward to work in Montana's growing cattle industry. This elder, named Spotted Eagle, is a member of the Crow Tribe, a group of Siouan-speaking natives that currently inhabit a reservation in southeastern Montana. So who are these people?

The Crow are one of the more interesting yet lesser-known tribes of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains. The Crow are a bit distinct from some of their fellow Siouan tribes. They allied with the U.S. government while their cousins, the Lakota and Cheyenne, decided to resist American expansion. They are thoroughly Christian and have survived thanks to the shrewd politics and adaptability of their leaders, who have not been afraid to compromise when necessary. Here is the fascinating story of this resilient tribe that will likely capture the imagination of the American public should "1883" become a hit.

The name 'Crow' is an out-group term

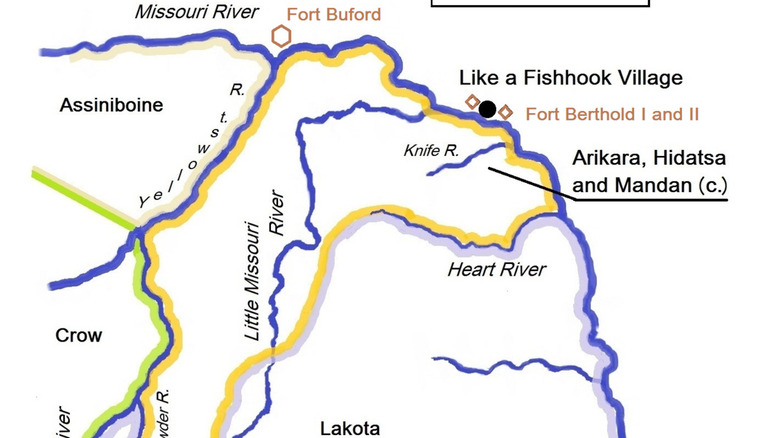

The Crow Nation's name stands out as one of the more peculiar ones to English speakers. "Crow" is the tribe's English name. But it is not translation of the tribe's native name. In fact, the name "Crow" is a creation of outside forces. According to a University of New Mexico dissertation by Crow Nation official Dr. Alden Big Man Jr., the Crow people were originally three different bands that claimed common descent and a shared language, but were not politically united. They called themselves "Biiluuke," which translates as "our side." The name, however, does not seem to have any ethnic connotations as the term "Crow Nation" does today. Their Siouan relatives the Hidatsa (territories pictured above) referred to them as "Apsaalooke" or "Absaruka" depending on dialect. Although Dr. Big Man notes that the term is difficult to translate precisely into English, it is generally translated as "children of the large-beaked bird" according to the Crow Nation itself.

Encounters with European settlers eventually led the Crow to adopt these foreign demonyms for themselves. French explorers referred to them as "Handsome Men." But neighboring tribes, when interacting with French explorers, would flap their arms like a bird in flight to describe the Crow. It is little surprise, then, that according to the Western Gazetteer, they became known by the French "gens de Corbeau." The name stuck and became "Crow" in English, the tribe's current official name. Meanwhile, the Crow adopted the name "Apsaalooke" as their Crow language demonym, which persists today as well.

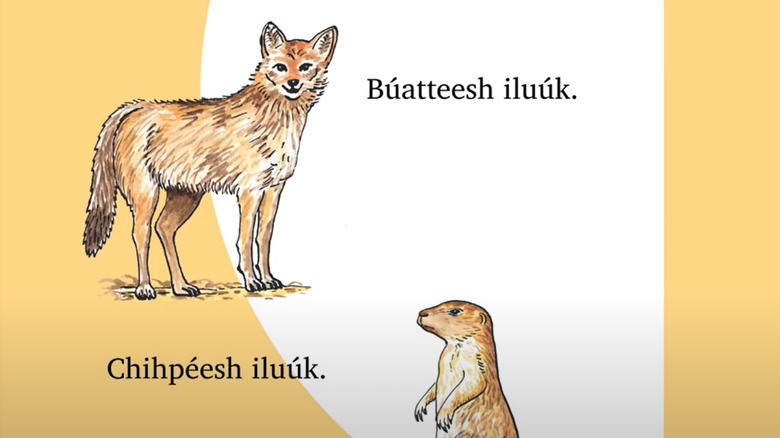

The Apsaalooke language is complicated

In his dissertation, Dr. Alden Big Man Jr. notes that the Crow are one of the few tribes that have managed to maintain their language at higher-than average levels. According to The Crow Nation, 8,500 Crow of a population of 10,000 speak it as a first language, although other sources such as Omniglot note that the real number is probably closer to 3,000 native speakers and numerous second-language speakers.

American students often struggle to learn English's Indo-European relatives such as Spanish and French, which are relatively easy compared to languages such as Apsaalooke. This language is classified as a polysynthetic languages. According to the Native Languages Project, these languages stack many small words to create very long ones that can sometimes express entire thoughts, such as the examples available from Lake Forest College. Thus, whereas in English, one would say "the Mountain people" (the name for one Crow band), according to Dr. Big Man Jr., in Apsaalooke, it's "Awaaxamiilixpaaka." Crow versions of familiar Christian prayers can be found at Christus Rex, giving an idea of what the language looks like compared to English.

According to Omniglot, Apsaalooke's closest relation is the Hidatsa Sioux language spoken in the Dakotas, while the Crow live in Montana. This suggests that the Crow were not originally from their current lands, but originated further east towards the Great Lakes region.

They were not from the plains

The Great Plains of the Western United States were home to many native groups by the time American settlers began colonizing them in the 19th century. But many of these tribes were relatively recent arrivals, too, including the Crow. According to the Little Big Horn College, the Crows' ancestors lived in a region which their oral tradition calls "the Land of Forests and Many Lakes." The name suggests an origin in the Great Lakes region of the United States and Canada, perhaps in Minnesota or one of the Rust Belt states. According to legendary folk migrations, this ancestral tribe underwent several splits resulting in three Crow bands and the Hidatsa tribe. The latter settled in the Dakotas, the rest in Montana and Wyoming.

The linguistic evidence suggests that there is some truth to these folk migrations, although they were probably not quite as simple as a chief having a dream telling him to find a new homeland for his people. Lake Forest College notes that the Crow language Apsaalooke is a Siouan language and is thus related to other languages spoken from Montana all the way to the Eastern United States. Linguist Ryan Kisak, therefore, argues that the Siouan languages originated much further to the East, perhaps even in the Ohio River Valley, and appeared on the Great Plains as a result of wars, land grabs, and displacements between warring tribes. If the folk histories are correct, the Crow would have reached their current homelands around the 15th century, or perhaps earlier.

Crow religion believed in one creator

Native American religion varied across the continent. According to Duke University, many tribes believed in some sort of higher divinity commonly and generically called the "Great Spirit." This is known as a "non-theistic" belief, and was common among Siouan groups such as the Lakota. But the Crow departed from this model. The tribe believed in a supreme creator god that made the world out of a mass of primordial waters.

The Crow creator is known in Apsaalooke as Iichikbaalia (via Little Big Horn College). Crow legend (via Jackson Hole Historical Society) recounts that this deity ordered the ducks to bring him mud, which he then breathed on. The mud expanded and became all the lands of the world. He populated the world and created the first man. Then, he created a woman from the man's rib and gave them many gifts from buffalo to tobacco. Interestingly, the man rejected the "gift of tears," which he could only regain through suffering.

According to Britannica, the Crow engaged in rituals called "vision quests," involving abstinence, fasting, and prayer, to grow closer to Iichikbaalia. These rituals interestingly parallel Christian customs of fasting and abstinence for sanctification. Thus, according to Native News, the Crow saw many similarities between Christianity and their own spirituality once it arrived in their lands. Among these are parallel creation narratives (see Genesis): an omnipotent creator who made Man in his image, and the resemblance of Catholic saints to animal and ancestor patrons of Crow religion. Thus, the Crow were receptive to Christianity, their main faith today.

Catholic Crows

According to the Tribal College Journal, Christian missionaries generally sought to suppress native spiritualities and assimilate natives into Euro-American society. The Crow, however, are the exception, retaining their customs while being unashamedly Christian. According to Native News, a significant number of Crow adhere specifically to Catholicism. Catholicism arrived with Jesuit Pierpaolo Prando, (via "Parading through History"), who catechized the Crow in their own language and their own cultural context, undoubtedly noting parallels between Crow spirituality and Catholic doctrine. He baptized Chief Iron Bull and his wife, both of whom adopted the Christian names Joseph and Mary, respectively, as the Christian "parents" of their tribe. Prando's translation of prayers and writing of Crow hymns quickly won over Iron Bull's band. The Jesuits converted other bands too, so when famous Crow chief Plenty Coups died, he had a Catholic-Crow funeral procession.

Unlike Protestantism, Catholicism allowed the incorporation of Crow customs. Thus, sweat lodges, purification rituals using cedar, and the use of the Crow language thrive to this day alongside crucifixes and Marian statues. The St. Charles Catholic Church on the Crow Reservation is decorated with Crow woodwork and embroidery. The Crow attitude towards this beautiful synthesis is encapsulated in the following slogan (via Indian Country Today): "Jesus is Lord on the Crow Nation."

They got their present lands in 1851

As the United States expanded westward, they encountered the Crow Tribe living on a large tract of land in the modern states of Wyoming and Montana — lands which the United States purchased with the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. According to Little Big Horn College, the Crow and the U.S. signed an 1825 friendship treaty to establish "perpetual friendship" between the two parties. In practice, however, it was a subjugation treaty. Under Article I, the Crow virtually surrendered their sovereignty, acknowledging the jurisdiction and supremacy of the U.S. government over their lands. They retained some degree of economic sovereignty, however, since the United States acknowledged them as a separate entity under American protection that the federal government transacted with.

Continuing problems with American settlers and tribal conflicts required a clearer treaty with all the Plains nations, so in 1851, the U.S. signed the Ft. Laramie Treaty (aka the Horse Creek Treaty) with the Crow and several other tribes. The treaty recognized the lands around the Yellowstone River as Crow territory, which rival tribes and the United States agreed to respect. However, there was no enforcement mechanism. According to the NPS, the tribes were not to attack settlers encroaching on their lands. When settlers entered the territory of the Crow's Cheyenne and Lakota rivals, war broke out and spilled into Crow territory, which soon was caught between two hostile parties. The Crow had no choice but to play their American and native rivals against each other in order to survive.

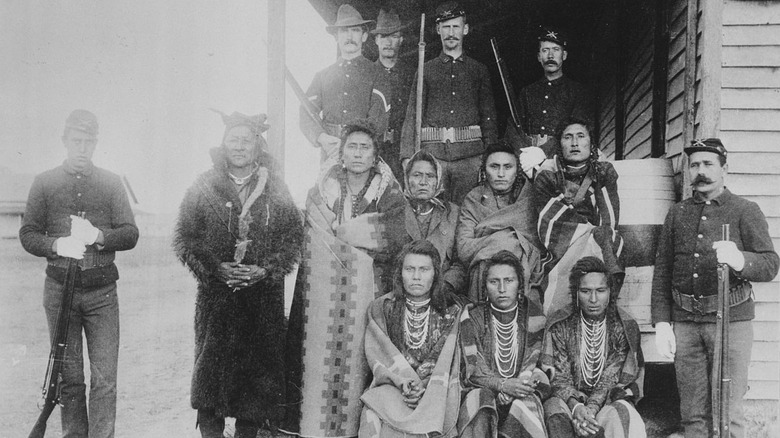

The shrewd politics of the 19th century

In 1862, a 14-year old chief Plenty-Coups, the last of the traditional Crow rulers, had the following dream, later recorded in his autobiography. The chief saw buffalo disappear from the Great Plains and get replaced with the cattle. He then was transported to a forest, which was promptly destroyed, leaving only a single tree: the house of the chickadee. In Crow tradition, the chickadee is the wisest bird that listens, learns, and minds his own business (or "pretends" to). According to the American Indian Relief Council, the chief's dream was interpreted to mean that Crow survival hinged on cooperation with American settlers and the United States government. Thus, the chief was told to educate himself on their ways and be ready to adapt to them.

According to the book "From the Heart of the Crow Country," the Lakota and the Cheyenne had become increasingly hostile to the Crow as settlers pushed them west out of the Dakotas. The Crow, caught between the United States and their rivals, allied with the latter. For this, other natives, according to Crow historian Olivia Williamson, labelled them traitors (via Great Falls Tribune). But Williamson noted that "you can't be a traitor to someone who is your enemy," suggesting that the Crow feared Lakota encroachment more than American expansion. Thus, the tribe provided the U.S. Army with scouts, which Sitting Bull's Lakota massacred alongside the U.S. 7th Cavalry at Little Bighorn. But the gambit paid off, and the Crow, who still inhabit their historic lands, commemorate the battle to this day.

A shrinking homeland

Despite their sympathies and alliances with the U.S. government, the Crow suffered from a gradual loss of land to settlers. According to the Crow Nation, the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 guaranteed the Crow a 38-million-acre parcel of land in Montana and Wyoming. But this land would be soon reduced. When gold was discovered in Montana, prospectors, hoping to get rich quick, trekked west using the Bozeman Trail through the Crow's Wyoming lands (via WyoHistory.org). Although the Crow helped protect miners from Sioux raiders, the U.S. government reduced their landswith the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. Under the new treaty, according to Intermountain Histories, the Crow surrendered 38 million acres in return for an 8-million-acre reservation in Montana. Wyoming was given over to ranching and American settlement.

Congress modified the Crow lands three more times. Railroad, ranching, and farming interests all played a role as the U.S. government sought to attract tourism and economic development to the area around Yellowstone National Park, a historical Crow hunting ground. The Northern Pacific Railroad cut through this area, and Chief Iron Bull was invited to speak, where he claimed to know the reason behind his invitation. His cryptic words suggest that by giving the final spike of the railroad to be laid, he was symbolically surrendering Crow lands. Thus, he believed, his people's days were "almost numbered." But although the reservation was cut to 2.3 acres, around 6% of the original territory, the Crow have survived, just as Chief Plenty Coups had hoped.

A matrilineal tribe

Plains natives had a variety of kinship systems. The Omaha, for instance, are strongly patrilineal. The Crow, however, are strongly matrilineal, according to the American Museum of Natural History. The Crow kinship system, which anthropologists use to describe all systems that resemble it, gives weight to the female line. The Crow system is relatively straightforward. According to the University of Idaho, the mother's female relatives were all called "mother." Biological sisters and their daughters are "sisters." Maternal uncles, nephews, and biological brothers are "brothers." Children of maternal uncles are just "children." Members of the father's matrilineal line are considered fathers (helpful visualizations are also out there). Thus, it is clear that the mother's ancestry was considered the focal point for tracing descent, and it showed in daily life.

Naturally, the matrilineal system emphasized clan identification with the mother's family. According to Native News, all children belong to the their mother's clan, not the father's, and trace their descent in this way. All matrilineal female relatives are expected to act as mothers to all clan children, while matrilineal males are expected to fulfill the traditional role of uncles, that of a second father who helps build up the child's esteem and confidence. Parents and matrilineal male relatives, however, are not responsible for discipline. The male paternal relations discipline children and ensure they stay on the right path. As a result, although they are not important for tracing descent, they are the most important and respected people in a child's life. But matrilineal does not mean matriarchal. Although women played an important role and could even become chiefs, such as Pine Leaf (pictured above), most Crow leaders were still men.

The badé

The term "Badé," according to Indian Country Today, is usually translated as "two spirit." This translation is a catch-all term that the Indian Health Services notes traditionally refers to Native Americans that took on roles and dress (such as above) traditionally ascribed to the opposite gender. Thus, a skilled male weaver or potter, or a particularly compassionate man, was a badé. So were women that enjoyed hunting, riding, and war. Since Badé had the gift of seeing the world through the eyes of both genders, they often held religious roles in Crow society.

The Badé are one of the more misunderstood aspects of Crow society because today, the term colloquially refers to LGBT+ Native Americans. Although Badé did sometimes engage in same-sex relationships, occasionally with the widow or widower of a close friend, things were a bit more complex. Although Badé were considered a distinct gender, it did not limit their participation in norms consistent with their biological sex. Thus, taking part in domestic tasks did not prevent a male Crow Badé from fighting in war or a female Badé from working in the home.

The badé institution was one of the first targeted by Europeans. Europe's Christian society had distinct gender roles that did not tolerate the fluidity seen in the Native American world. Thus, the badé were forced to conform to their biological sex and get out of same-sex relationships. Conversion to Christianity among the natives suppressed the tradition definitively, although there have been attempts since the 1960s to revive it.

They gave their name to a partition attempt

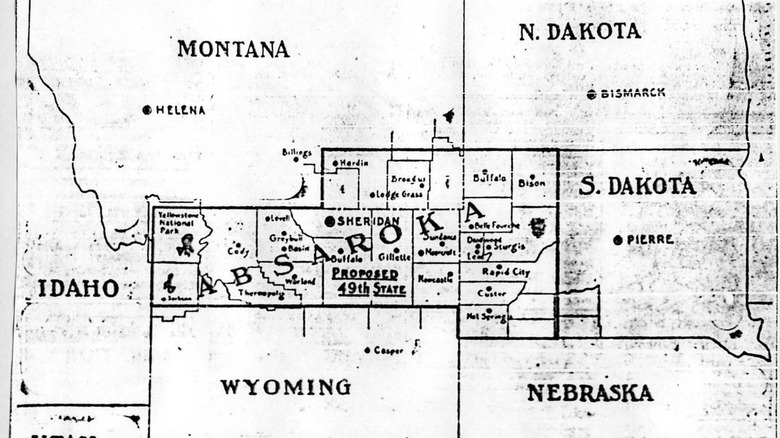

Today, the Crow Nation exists on its reservation in Montana. There is no Crow state (although the reservation is technically sovereign per the NCSL), and generally, Crow culture ends at the reservation's borders. But there was a time when the Crow tribe gave its name to an attempt to create a new state out of Montana, South Dakota, and Wyoming.

In 1939, Republican and libertarian voters of Northern Wyoming were increasingly disenchanted with the distribution of President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal funds. According to South Dakota Magazine, Wyoming's Democratic Party favored larger towns and industries in the south of the state, over the rural, mostly-Republican north. So the inhabitants of Northern Wyoming, joined by Montanans and South Dakotans, set up their own state called Absaroka with its capital at Sheridan. The new state's boundaries included the Crow reservation.

It is unclear why the partition's proponents chose a Crow name for their state. Absaroka's core lands in Wyoming, which historically belonged to the Crow under the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty. But there is nothing that speaks to the tribe's view on the venture. One can speculate, however, that they probably opposed it. According to Little Big Horn College, the Roosevelt Administration appointed Crow chief Robert Yellowtail as superintendent of the Crow reservation, the first Native American to hold the post. Yellowtail engineered the cession of over 40,000 acres of land to the Crow Tribe from White ranchers and used federal money to economically develop the Crow lands. Thus, it is possible that the ranchers that supported Absaroka were in part motivated by these land disputes with the Crow. How ironic, then that the new state should have been named after the tribe.