What Is The Ancient Egyptian Ebers Papyrus?

So we all know that ancient Egypt was big on the afterlife, right? Embalming, mummification, preparation for the journey into the world of the dead, and so on. As Dr. Stephen Buckley, archaeologist from the University of York, told the BBC, "The afterlife was just a continuation of enjoying life. But they needed the body to be preserved in order for the spirit to have a place to reside." Buckley goes so far as to say, "Egyptian mummification was at the heart of their culture."

It makes sense, then, that ancient Egyptians took extra pains to take care of their body when they were alive. Healthcare and medicine, personal cleanliness, even the application of cosmetics: All of it blended together into one cultural, spiritual bundle. Keeping things fresh and healthy helped prep the body for death. For instance, World History Encyclopedia goes into detail about daily beauty regimens that rival ours today, for both men and women, commoners and royalty: baths, wigs, tooth brushing, skin creams, deodorants, and more.

This kind of attentiveness to the body, exemplified in the painstaking process of mummification, illustrates exactly how well ancient Egyptians understood human anatomy. Granted, they didn't discover penicillin, use microscopes, or develop vaccines based on cellular biology. But, they were big into what today we call homeopathy. One vital historical document, in particular, illustrates the extent of their medical knowledge: the Ebers Papyrus.

Diagnoses, treatments, the gods, and homeopathy

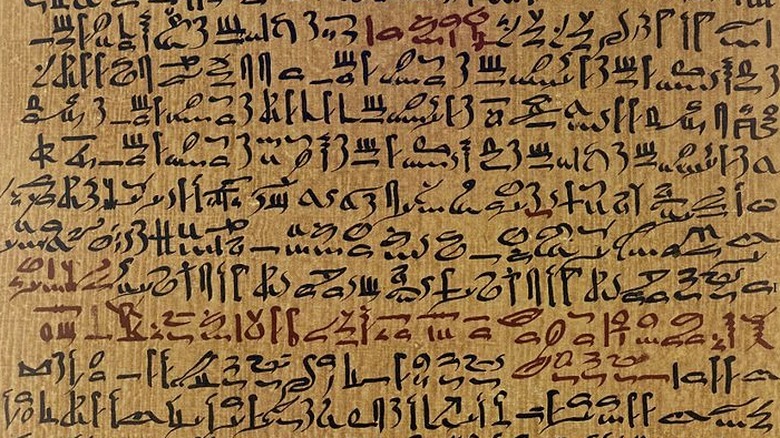

So you know "Gray's Anatomy"? Not the TV show, but the 1858 landmark medical textbook that stands as a benchmark for surgeons even today. The ancient Egyptian Eber's Papyrus is kind of like proto-modern version of that, plus a comprehensive diagnostic and treatment manual. It covers conditions ranging from asthma to arthritis, diabetes to gastrointestinal problems, as well as contraception and fertility treatment, how to set broken bones, how to surgically remove tumors, and much more (as sites like Ancient Origins and Egypt Today state).

To be clear, the Eber's Papyrus's 877 rubrics (sections with headings) and 108 columns contain lots of talk about the gods, pseudo-magical stuff, and plant-based remedies. The document also focuses on the flow of fluids through the body, particularly as how they relate to the heart and cardiovascular system. Its language isn't technical, either. Line 763, for instance, reads, "Flow out, fetid nose, flow out, son of fetid nose! Flow out, you who break bones, destroy the skull and make ill the seven holes of the head!" This basically sounds like grandma's advice for a cold: get all the snotty, sneezy garbage out of your body.

Additional excerpts on CME30 focus on pregnancy. They advocate breastfeeding for three years, the use of oil and fat to induce an abortion, and rubbing the abdomen with saffron powder and beer to help with a difficult childbirth.

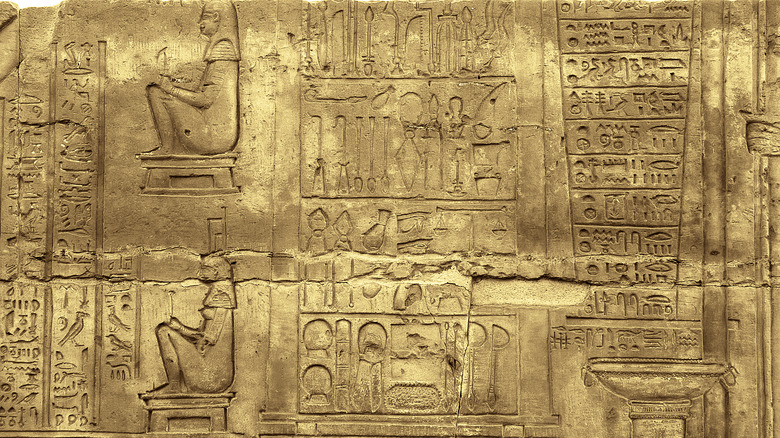

Discovered between the legs of a mummy

As Ancient Origins relates, the Eber's Papyrus dates to the beginning of Egypt's New Kingdom (1550–1070 BCE, per the Australian Museum). Specifically, it dates to the reign of King Amenhotep I (1525-1504 BCE), second king of the 18th dynasty (1550–1295 BCE). However, its information likely dates back to the Middle Kingdom's 12th dynasty (1981–1802 BCE), about 600-700 years after the Pyramids at Giza were built (2589-2503 BCE, per History). This means that the Egyptians had been refining their medical methods long before they were put to paper in some sort of official, codified way. It was also written in Egypt's everyday script, hieratic, not the pictorial hieroglyphics folks commonly associate with them.

As the History of Information states, the Eber's Papyrus first cropped up along the antiquities circuit in 1862. It was apparently first discovered "between the legs of a mummy" in Thebes, the main city of Upper Egypt in the south, and bought by American dealer Edwin Smith. It stayed with Smith, who also owned the eponymous "Edwin Smith Papyrus" (another medical codex), until he sold it in 1869. From there it was bought by German Egyptologist Georg Ebers in 1872, from where it gets its current name. At present, it's located in the University of Leipzig Library in Germany. We're lucky that the papyrus, a fragile and easily destroyed material, survived long enough to pass along to us such a crucial piece of our picture of ancient Egypt.