The Untold History Of The Aba Women's Protest

When the British colonized Nigeria, they paid little attention to the preexisting power distributions and instead installed their own form of rule. In doing so, they stripped the women of the region of many of their traditional rights and freedoms. After 15 years of indirect rule, as a rumor circulated that the women of Southern Nigeria were about to receive another blow, women came together to stand up against this colonial imposition.

Also known as the "Ogu Umunwanyi" in Igbo, "Ekong Iban" in Ibibio, and the Women's War, the Aba Women's Protest bewildered colonial officials, who didn't understand the traditional protest methods used by the women (per Global Nonviolent Action Database). But even if British colonial forces didn't understand what was going on, they realized that a protest by thousands of women was a force to be reckoned with.

There were numerous uprisings against colonial rule during Nigeria's history. The Aba Women's Protest is notable in being one of the first major protests against British rule.

Indirect rule in Southern Nigeria

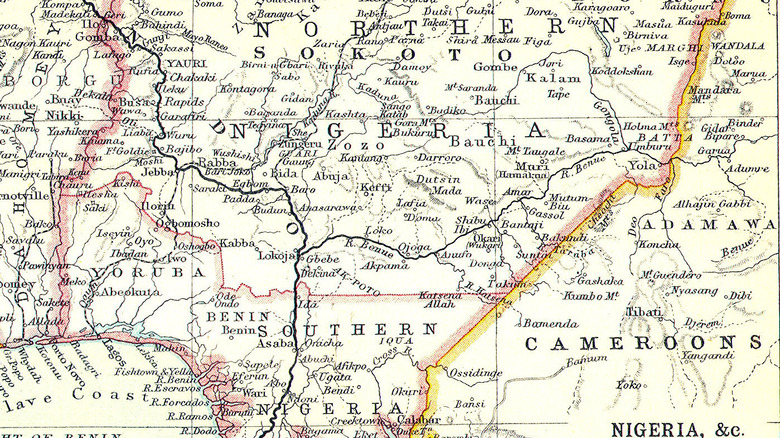

On January 1, 1914, Lord Frederick Lugard consolidated the Northern Nigeria Protectorate and the Colony and Protectorate of Southern Nigeria to create the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, Lugard's wife, Lady Flora Shaw Lugard, was the one responsible for coining the name "Nigeria." Lugard instituted a system of indirect rule in Southern Nigeria, where Igbo individuals were appointed to be "warrant chiefs" by British administrators to rule locally, Pulse writes.

According to the book "'Pogrom'" by Philip Eze Ehirim, Lord Lugard imported this administrative concept into Nigeria after having seen the policy in action during his time in India and Uganda. Lugard instituted indirect rule in northern Nigeria in 1900, well before the amalgamation of Nigeria. Ehirim writes that by 1928, indirect rule was introduced in Eastern Nigeria as well.

These warrant chiefs became "the enforced symbol of power" and before long, they became more and more oppressive and corrupt. According to Black Past, the warrant chiefs "seized property, imposed draconian local regulations," and imprisoned anyone who openly spoke out against them.

The colonial tax census

In September 1929, British colonial administrator Captain J. Cook decided that the taxable wealth of the Igbo people was to be reassessed and should also "count the women, children, and domestic animals." Between late October and mid-November, Mark Emereuwa, the representative for warrant chief Okugo, went to Oloko to conduct this tax census.

In the book "Colonialism and Violence in Nigeria," Toyin Falola writes that the news about the tax census turned into a rumor that Igbo women would have to pay tax as well. When Emereuwa asked Nwanyeruwa Ojim, a widow who was worked processing palm oil in Oloko, to "count her live stocks and people living with her," Nwanyeruwa Ojim understood this to mean that she was to be taxed based on the final outcome.

In response, Nwanyeruwa Ojim asked Emereuwa, "Was your widowed mother counted?" which expressed the notion that "women were not supposed to pay tax in Igbo society," according to Pulse. The two proceeded to get into a physical altercation and as they "seiz[ed] each other by the throat," per American Historical Association, Nwanyeruwa Ojim poured palm oil on Emereuwa. After getting away, she quickly spread the news of the incident, giving "the rumor the wings to fly."

The market women revolt

The women needed no further convincing. Although there wasn't actually going to be a tax on women, by that point they had more than enough actual grievances. In an oral interview, one woman stated that "The new Chiefs are also receiving bribes. Since the white men came, our oil does not fetch money. Our kernels do not fetch money. If we take goats or yams to market to sell, court messengers who wear a uniform take all these things from us," per "Colonialism and Violence in Nigeria."

Led by Ikonnia, Mwannedia and Nwugo, three leaders of the network of women in Oloko, news of the upcoming protest spread. According to the Global Nonviolent Action Database, the women sent out palm leaves to neighboring villages as a "symbol of invitation" for the protest being organized. After receiving a palm leaf, each woman passed on the leaf and the message.

Pulse reports that up to 10,000 women gathered in Oloko to demand a written assurance from Okugo that the women wouldn't be taxed. But although they were given the assurance, Okugo also took several protesters hostage and harassed them. In response, the protest only grew and women now called for Okugo to be removed. After two days, the women couldn't believe their good fortune when the British officials not only removed Okugo, but also sentenced him to two years imprisonment. Hearing of this success, the protest spread to wherever women wanted corrupt warrant chiefs removed.

Pre-colonial methods of protest

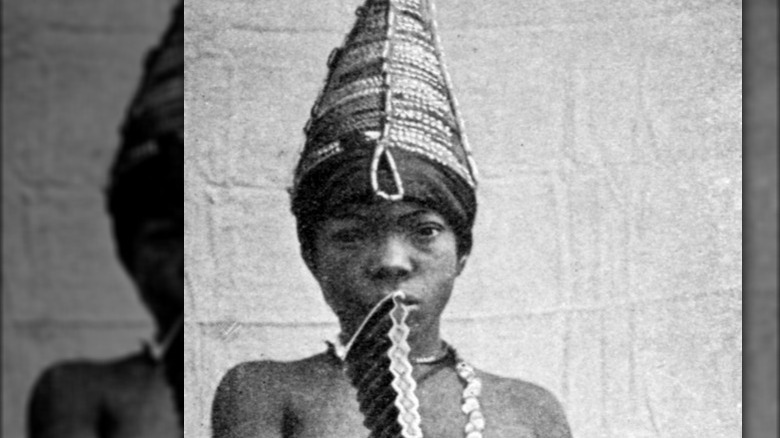

As the campaign to remove corrupt warrant chiefs spread, women called their protest "the Ogu Umunwanye," or "the Women's War." The campaign was understood as a women's movement, but it followed the pre-colonial understanding of gender, which can be seen in the method of protest.

During the Aba Women's War, the women protested by "sitting on a man," a method which involved publicly shaming a man who had acted disrespectfully. The Global Nonviolent Action Database writes that this entailed following warrant chiefs around, while dressed in traditional war garments, singing traditional war songs loudly day and night to inconvenience the man as much as possible. Because this form of protest was aimed at forcing the subject to pay attention, the man's hut would often be burned down as well.

According to "Recovering Igbo Traditions" by Nkiru Nzegwu (via Oxford Scholarship Online), this method of protest historically "afforded women a powerful constitutional check on male excesses in society, and assured that their views were adequately factored into policy decisions."

Black Past writes that as the protests continued to spread, the women attacked European-owned stores and Barclays Bank and released imprisoned people from prisons. They also burned down several district offices and 10 colonial Native Courts, seen as "as an extension of the practice of burning down a man's hut." A number of European factories were also looted.

The protests spread

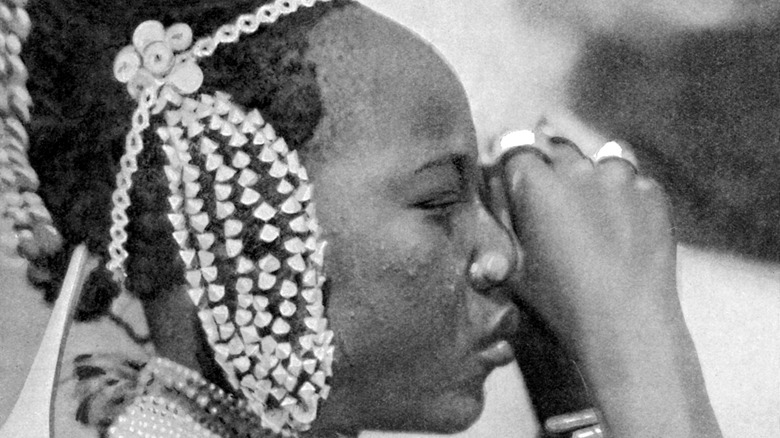

By December 1929, the protests spread from Owerri and Aba to Calabar and soon included numerous people from various ethnic groups, including Igbo, Ibibio, and Opobo. Women across Igboland saw that they didn't have to put up with corrupt warrant chiefs and that for once, the British colonial administration might listen to them.

However, as Nzegwu notes in Recovering Igbo Traditions, the women weren't protesting to overthrow colonial rule. Instead "they just wanted to be consulted on the selection of Native Affairs officials, and in the formulation of policies." While they did want the corrupt warrant chiefs and court clerks to be prosecuted, they advocated the introduction of "safeguards in the administrative system" rather than dismantling the system itself.

The protests lasted two months, and at least 25,000 Nigerian women were involved. The British administration didn't understand the women's motivations and forms of protest, however, and in mid-December, the British colonial administration called in police officers and troops, who shot into the crowds of protesting women, according to the Global Nonviolent Action Database. Pulse writes that the colonial police and troops killed over 50 women and one man in addition to wounding over 50 others.

Legacy of the Aba women's protest

The women's protest was also the "first major challenge to British authority in Nigeria and West Africa during the colonial period," writes Black Past. There were some significant victories. During the protest, several warrant chiefs were removed or stepped down "because of the [women's] constant pressure and nonviolent harassment," according to the Global Nonviolent Action Database. Some groups also received "written assurances" that a tax wouldn't be implemented on women.

The British colonial administration also realized that they had to offer more colonial power to women and couldn't easily impose the European patriarchal gender binary on the colony. Libcom writes that as a result, women were given the power to be warrant chiefs in some areas and were also able to be appointed onto the Native Courts. A commission of inquiry set up by the governor of Nigeria in 1930 also found that the women "had good grounds for supposing that [direct taxation] was afoot," per "Colonialism and Violence in Nigeria."

This wouldn't be the last time that women in Nigeria rose up in protest. Throughout Nigeria's colonial rule, the Tax Protests of 1938, the Oil Mill Protests of the 1940s, and the Tax Revolt of 1956 would all be inspired by the Women's War.