Medical Procedures That Existed In Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egyptians left quite a substantial number of medical texts behind which are an invaluable source of the various practices they used, writes Justin Barr in an article in the Journal of Vascular Surgery. The Edwin Smith Papyrus, The Brooklyn Snake Papyrus, and The Ebers Papyrus contain age-old conclusions on anatomy, physiology, pharmacology, and others fields.

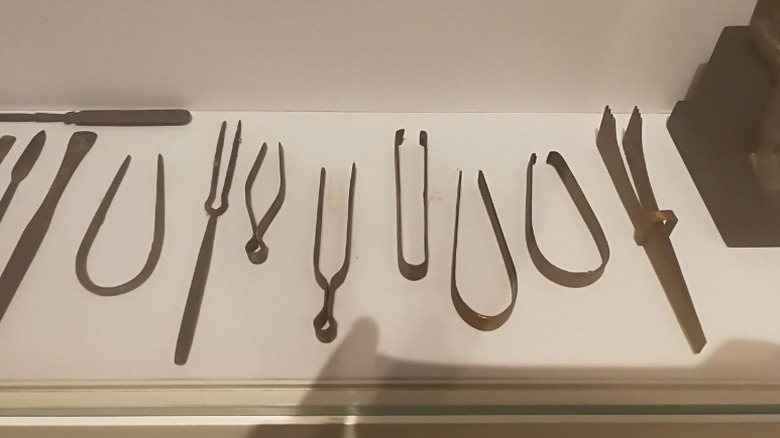

Not many surgical tools were found during archeological removals, and so far, only one portrayal of surgical medical procedure was found — depicting male circumcision. There was no evidence of considerable surgeries in any of the 30,000 mummies inspected, so the general idea of ancient Egyptians executing complex medical procedures is false. Archeologists did find some traces of amputations, healed fractures and treated wounds, but Egyptians spared most of their surgical magic for the dead.

Their view of the body was holistic, meaning they believed people have bodies and souls. As a consequence, there were different practitioners who took care of people's health: magicians, priests, and swnw, also known as natural healers. The latter most resembled modern-day doctors, using herbal medicine and — in some cases — even basic operations. They used some extreme measures for healing diseases, such as larvae and dung therapy, but more often they treated patients with herbs and other substances. Many of these substances are proven to contain healing properties, which shows that Egyptians knew more about pharmaceuticals then surgeries. Here are medical procedures that existed in Ancient Egypt explained.

Amputation

Although ancient Egyptian medical texts and wall scribing imply the idea that Egyptians executed complicated medical operations, archeological excavations show a different story. According to a research paper in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, a discovery in Dayr al-Barshā is the only confirmation that ancient Egyptians did use amputation with the intention to heal the individual.

Four different cases of amputation were found: two cases of both legs' amputation and two cases of arm amputations, one cut below the elbow and other one higher up near the shoulder. It seems that the patients who lost legs used some form of prosthetic accessory to replace the lost limbs. In one patient with arm amputations, the evidence shows the person was exposed to a traumatic event that injured the arm, so they cut it off, but the patient still died shortly after.

As noted in another article published in The Lancet, there are other cases that support the theory that amputation was a part of ancient Egyptian medical practice after all. One case reveals the amputation that followed some form of injury: The lower part of the arm was amputated, which resulted in "distal synostotic fusion of radius and ulna," an incorrect healing of the rest of the limb. Another case revealed a more complex medical interference, where a part of the skull bone was missing; the scientists believed it was removed through some kind of surgery.

Vascular surgery

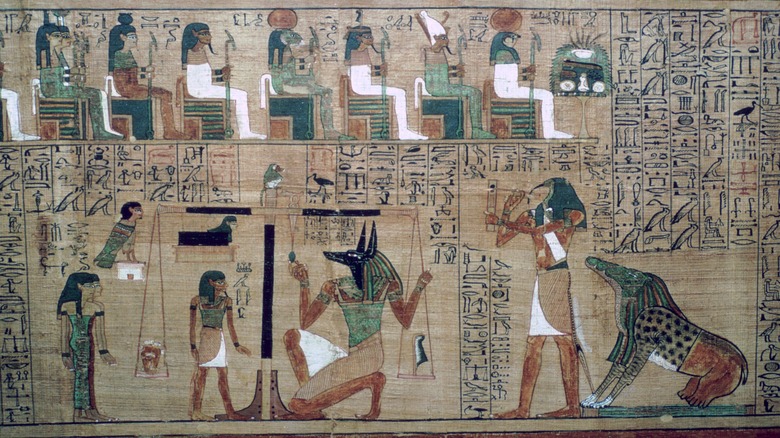

The heart was the most important organ for Egyptians, and they believed it was the essence of human experience, combining the body, spirit, and the soul, explains Justin Barr in the Journal of Vascular Surgery. According to The Papyrus Ebers, the heart is the center of the body, with vessels connecting different organs to it. Egyptians defined and counted these vessels very specifically, mapping the whole body with a simple version of the vascular system as we know it today. They believed that when the connection between heart and specific organ is disrupted, the result is disease.

Besides detailed information about the cardiovascular system, The Papyrus Ebers contains advice on how to treat specific vein disorders. If there are snake-like shapes filled with air all over the limbs, there "is an enemy of the vessel." Another description characterizes the oldest definition of arterial aneurysm, with instructions stating that a swelling vessel needs to be treated with a knife heated in fire. But it has to be noted, so far, no archeological evidence was found that would confirm that these types of operations were ever carried out.

Other solutions in The Papyrus Ebers are very simple, such as the one for dryness in the heart: If "he sighs often and his Heart is eaten up with anger; this is because his Heart is full of Blood, which in turn is due to drinking Warm Water and eating Bad Food." For diseases like this, a combination of honey, milk, and water is recommended.

Prosthetic Dentistry

Certain writings can be found in hieroglyphic texts which confirm that Egyptians did have dentists, explains R. J. Forshaw in an article published in the British Dental Journal. But again, the detailed research into the matter revealed that Egyptians mostly used pharmaceutical means to treat dental issues — even bodies of powerful pharaohs such as Amenhotep III and Ramesses II revealed the horrible state of their teeth.

There were some speculations, based on tens of thousands of excavated human remains from Dynastic Egypt, that Egyptians did use surgery for treating dental abscesses. In one example, described in 1917, two artificial holes were drilled into a tooth root, which could indicate that an ancient dentist tried to drain the abscess with this procedure. The case was later pronounced improbable, with a statement that Egyptians did not have the right tools to complete this kind of operation.

The idea of ancient Egyptians using prosthetic tools was also popular in the past. Archeologists found pairs of teeth connected with a thin gold wire, which held teeth in place. This resembled a modern-day tooth bridge, where the missing tooth is replaced by a fake one. But as it turned out, after close examination, the fake teeth were inserted post-mortem, maybe to prepare the individual for afterlife. The only case of tooth prosthetics, which could be defined as an actual medical procedure, were found in an individual who might have come from abroad — to be fair, Greeks and Romans were way more advanced when it came to dental surgeries.

Treating caries and gingivitis

Caries wasn't a common problem in Egypt, due to their diet lacking sugar. But, if a cavity appeared, they treated it by using different fillings that helped to heal and fix the tooth, as described in the British Dental Journal.

Seven out of 18 recipes and procedures described in medical papyri detail a method of applying different ointments and materials around and over the aching tooth: to fill the hole, fix the tooth, and relieve the pain. Egyptians used this as some form of tooth bandage, which hardened up, covering the aching tooth, and defended it from hard particles or additional inflammation. In one case, The Papyrus Ebers recommends a paste made out of crushed seeds, honey, and ochre powder. They used terebinth resin and malachite crystals frequently, along with cumin, carob, gum, oil, and other materials. Willow bark was used as well. It has to be noted, many of these ingredients did actually have anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties.

Fumigation and douching for gynecological issues

Egyptians, similar to Greeks, saw the womb as a mystical organ, sometimes traveling around the body. The disease of the womb was often guilty of causing other symptoms as well, such as eye problems or neck pain, so when treating the symptoms, one had to address the womb first. They had several different procedures, as Lesley Smith describes in an article in the Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care (via BMJ Journals), each for a specific problem, which included fumigation of vagina, abdominal massage, and pharmaceutical means, some inserted inside of the body, applied to skin, or consumed.

As per The Papyrus Ebers, a displaced uterus can be treated in several different ways. By drinking a mixture of wood mold and beer, or by soaking genitals in the fumes of burning wax or even dried human excrement. Another procedure prescribes rubbing the woman in honey and crude oil. Besides fumigation, they used vaginal douching as a therapeutic procedure as well. They often used a combination of garlic and cow horns, as they believed it healed many diseases.

Egyptians had a method for suspended or irregular periods as well, explains Petra Habiger, school health counselor and writer of "Menstruation, Menstrual Hygiene and Woman's Health in Ancient Egypt" (via Museum of Menstruation). A mixture of oil, fruit, and beer should be eaten for four days. Another herbal blood laxative was applied to the pubic region, followed by myrrh fumigation. They were even the first to use tampons, made out of papyrus plant material (via ThoughtCo).

Inducing and preventing labor

According to Lesley Smith's article in the Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care (via BMJ Journals), Egyptians had several means of contraception, and many people now may have heard about the infamous crocodile dung contraceptive method of ancient Egyptians, but the method is often understood wrong. The papyrus describes a prescription where "crocodile dung is inserted into vagina and packed against cervix as a contraceptive," but not through direct contact, but by burning the dung chopped over sour milk as an incense and fuming the vagina. Besides dung, they used another technique of sprinkling honey over the womb while a woman was laying on a bed covered in natron mineral dust. On other occasions, they used "incense, fresh oil, dates and beer."

As per The Papyrus Eber, abortion was done solely through non-invasive means, by mixing dates, onions, honey, and acanthus fruit, then applying the paste through a cloth inserted into a woman. They used this method throughout pregnancy. To induce labor on the other hand, they had a variety of techniques: from applying peppermint or pouring warm oil on genitals, plastering salt and herbs to the abdomen, to inserting wasp dung balls into vagina.

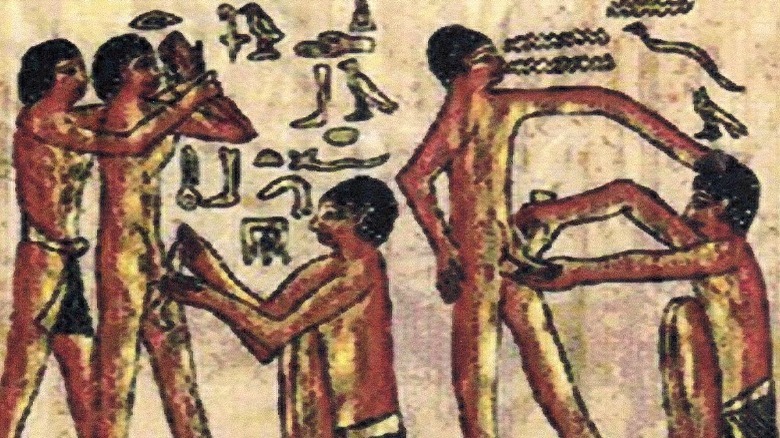

Circumcision

Although some scholars believe ancient Egyptians were the first civilization to invent circumcision, many cultures across Africa, Middle East and even Oceania practiced this ritual, according to Ancient Origins. In ancient Egypt, this ritual was not for everyone. They practiced it as part of initiation into priesthood, and the traces of the procedure were also found in bodies which belonged to the nobility class, so it is possible that it was used to differentiate individuals from commoners. And unlike circumcision in most western cultures, Egyptian circumcision was not complete — only a part of foreskin was removed.

There are several wall carvings portraying circumcision all over Egypt, with scenes depicting initiation. The oldest one discovered so far is in Ankhmahor's tomb, dating back to sometime between 2355 and 2343 B.C. The scene displays a young male being circumcised by a Hamitic priest using a knife, as explained by a study published in Voice of the Publisher. In fact, as per Beryl Hirschfeld in "The History of the treatment by extension of fractures of long bones," the stone knives used for circumcision are among the oldest medical tools found in human history.

On top of that, it is believed that Osiris, the first king of Egypt, introduced the practice of circumcision to Egyptians.

Bone fractures and dislocations

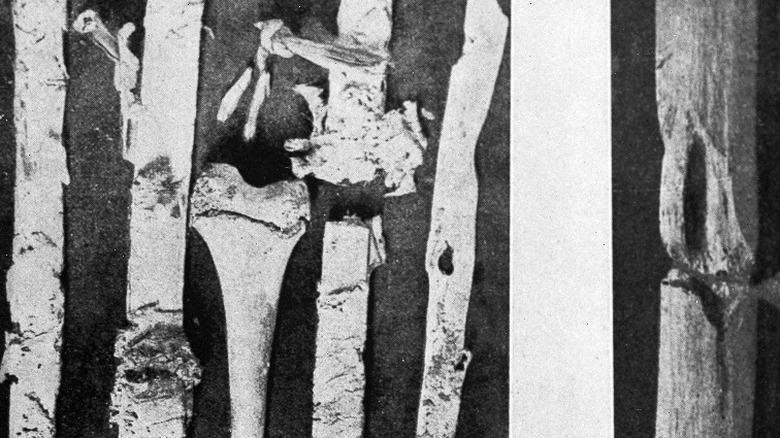

According to Beryl Hirschfeld in "The History of the treatment by extension of fractures of long bones," the oldest evidence of intentional fracture healing was found in ancient Egypt, near Luxor. The bodies belong to humans living between 4500 and 5000 years ago, showing clear signs of bone fractures treated with splints, the oldest ones in the world.

In one case, the researchers managed to confirm that the body belonged to a 14-year-old girl. She had a fracture of right thigh bone and was treated with a help of four splints, holding the bones in place. The splints were wooden, wrapped up in linen bandages. Unfortunately, no traces of actual calcification were found, meaning the treatment was not successful and the girl died. These unsuccessful treatments happened often, sometimes ending in bone "shortening, displacement and other deformities." Another case reveals a "compound fracture of both bones of the forearm." In this instance, the treatment was more successful, as they used a combination of grass padding and bark splints. There is some evidence in the texts from the early Egyptian period, 3000 to 2500 B.C., that Egyptians used same procedures on dead bodies as well. When tomb looting resulted in fractured mummies, they treated them to make them complete for the afterlife.

As per R. Sullivan in an article in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, ancient Egyptians knew how to treat dislocated bones as well. The procedure of relocating a jawbone, described in the Edwin Smith papyrus, hasn't changed until today.

Wound healing

Egyptians were really skillful when it came to treating wounds, applying bandages, and treating infection or inflammation. According to a study published in the World Journal of Surgery, their view on wounds was very peculiar — they believed that any kind of dangerous energy, such as demons, can enter the body through its holes. A wound was another hole which needed to be protected from this invasion, and they often chose animal dung to close this opening. They thought that demons would be repulsed by dung and leave the patient alone.

Egyptians knew very well about the healing properties of different substances to affect inflammation or infection, so they often used willow bark along with copper and sodium salts. They also used heliotherapy, exposure to the sunlight, and cauterization with fire flame. They were really good at wound dressing — think of the mummies — and used linen of different thickness for bandages. If the wound needed stitching, they closed it with adhesive tape or stitches as we know today. Sometimes, they applied fresh meat for the first day of therapy but continued with honey, grease, and herb ointments. They even used sour, moldy bread to prevent bacterial infections.

When it came to animal dung, they regularly treated wounds with fly muck — a combination of insect spit, excrement, and wall dust. Another therapy was larval therapy, where maggots are introduced to the wound, to clean and heal the tissue. Both therapies have proven medical efficiency and help to heal the wound faster.

Anus inflammation procedure

According to Justin Barr in a study in the Journal of Vascular Surgery, Egyptians put a lot of emphasis on the anus (the whole lower intestines, actually), describing it as an important organ, which produced wekhedu, "a poisonous substance that caused disease." This substance needed to be moved around or extracted, depending on the symptoms of the patient.

The Payprus Ebers describes a treatment procedure for the anus, which helps to "cool the anus ... reduce the smarting in the anus," and heal sores and diseases. The therapy started with a cooling anus remedy made out of the tail of the mouse, onion, honey, and water, mixed and taken orally for four days. The next step was an anal pill, containing antelope fat and caraway. After this, another anal suppository was inserted, made out of cow horn, dried oil, and wine yeast. When this was finished, they poured boiled milk, honey, wonderfruit, and ox bile on the anus for a day, finishing off with a paste of goose eggs and goose guts slapped over the anus.

Treatment of spinal injuries

There are six cases of diagnosed spinal injuries in the Edwin Smith papyrus described in detail: As explained in a paper published in the European Spine Journal, those diagnoses contained "highly accurate descriptions of signs and symptoms of different types of spinal injuries."

These descriptions show that Egyptians had an understanding on how important the spine is, even if they hadn't developed complex means to treat it yet. They defined "significant symptoms" for which doctors must look when diagnosing the patient, including lack of rotation and stiffness in the neck, how the patient contracts their legs when lying down, or "unawareness of both the arms and legs." They even described "autonomic dysfunction in spinal cord injury" — a condition where automatic processes, like breathing or digestion, are affected by spinal cord damage — by recognising "priapism, urinary incontinence and abdominal distention." Some cases include descriptions on how the patient was injured, showing they knew how important this is in such circumstances.

But, regardless of their correct descriptions, the treatments that followed weren't that effective. Two out of six described injures are labeled as incurable, and three of them were treated without medical surgery. Take case 32, for example: "Treatment instructions for a subsidence in a vertebra in the back of his neck." The Edwin Smith papyrus prescribed binding a patient over fresh meat and leaving him to rest, followed by loosening his bandages, applying ointment, putting the bandages back, and treating the patient with honey for the rest of the healing period. The patient needed to sit upright the whole time, which is really what the treatment actually amounted to.