What Hygiene In America Was Like 100 Years Ago

Correction 03/28/22: A previous version of this article stated that King Gillette invented the safety razor in 1904. He improved it with a patent for a disposable razor, not invented the safety razor.

Walk through any modern, 21st-century store and it's a guarantee there's an almost overwhelming number of hygiene products on the shelves. Whether it's meant to keep skin smoother, body odor at bay, or keep hair either thicker and more luxurious or gone altogether, Americans take their hygiene very seriously these days. It wasn't always like that, though, and it wasn't that long ago that deodorant wasn't on anyone's shopping lists. And soap? What's that?

According to the Smithsonian, 19th-century Americans had an interesting take on personal hygiene. A big ol' layer of dirt was thought to protect a person from things like the so-called "miasmas" that floated through the air and made a person sick, while things like regular baths were viewed as the sort of thing poncy Europeans did all the time. Americans were tougher than that — and they didn't have time for such nonsense.

Germ theory meant that things started changing with the Civil War, but for most Americans, baths and personal hygiene remained low on the to-do list until the end of the century. Then, things really started to change on a widespread scale as the nation came out of World War I and into the 1920s. It may have been just 100 years ago, but that generation helped to shape the way modern Americans care for themselves in some surprising ways.

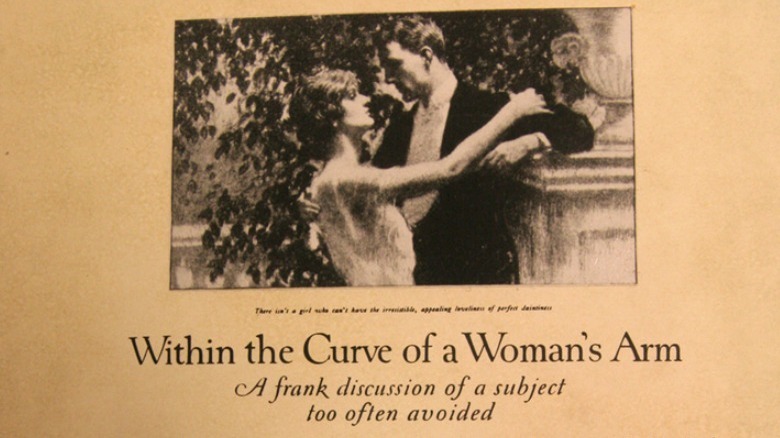

Deodorant advertisements were working

According to The Week, it wasn't until 1888 that the first commercial deodorant hit the shelves, but it was less-than-ideal. It took another two decades or so for another, less acidic deodorant to be invented, but it wasn't until the 1920s that marketing did some serious magic.

The concoction was originally invented by Edna Murphey's surgeon father, and it was meant to keep hands sweat-free. She named it Odorono and tried selling it to people for their pits, and it was initially a complete failure — until, that is, she hired a marketing team. Sales did just alright, and it wasn't until 1919 that marketing realized what the problem was: People knew there was a product out there that could stop body odor, but they just didn't know they needed it ... yet. So, the Smithsonian says they kicked off a campaign against B.O., taking out a series of advertisements with the same message packaged differently: Women, don't stink or you'll drive away the men.

It was the brainchild of a copywriter named James Young, who later wrote in his memoir that his suggestion that body odor was offensive did some serious damage to his own relationships with women, and while there was some serious outrage, Odorono sales rose 112% in that year. By 1929, it was a million-dollar company, and by the end of the 1920s, they had successfully convinced American women that deodorant needed to be a part of the daily hygiene regimen.

Germ theory gave rise to bathing and some serious competition

It wasn't until the end of the 19th century that bathing became a fairly regular thing, and according to the Smithsonian, a lot of America's hesitation was simply a lack of access to clean water. Bath houses started being built in the 1890s, but it took a while to catch on — and even when it did, bathing wasn't quite the same as it is today.

As the U.S. rang in the Roaring Twenties, it's safe to say that bathing was commonplace, but soap was less so. Even though some bathhouses had initially attracted some customers by handing out soap, cosmetics companies had also seen the trends and hopped on the bandwagon. Soap companies found that they needed to convince consumers that they should be using their product to get clean, and so-called "cosmetic cleansers" were such a threat that Big Soap organized into a trade association called the Association of American Soap and Glycerine Producers. They then created the Cleanliness Institute with the goal of teaching the public why soap was better than, say, bathing with cold cream.

Research from the University of Arkansas at Little Rock found the Institute's advertising, news releases, and hygiene materials ended up being a wildly important service to public health. Even schools started teaching children the importance of using soap, and by 1930, it was the norm.

Safe toothbrushes were new-fangled inventions

Dentistry has always been pretty horrible, and hey, that's one thing modern humans have in common with our ancient ancestors. Even though the University of the Pacific's School of Dentistry says that toothpicks have been used as far back as 5,000 years ago — if not back into prehistoric times — it was only in the 1920s that humankind got a decently pleasant toothbrush.

At the end of the 19th century, American toothbrushes were mostly made from bone handles and boar bristles, so that's gross. Attempts at getting rid of the bone resulted in toothbrushes with "inherent combustibility," and by 1920, the few Americans (about 20% of the population) who even had a toothbrush had one that was imported from Japan. What about the dental hygiene of that other 80%? The New York Times says they were probably just better off not brushing their teeth, as the brushes of the era were so stiff they could do more damage to gums than good to teeth. That's not really surprising: Look at boar bristles under a microscope, and can you blame people for not wanting to brush with tiny, hard spears?

That's not to say that people didn't care for their teeth. Falmouth Dental Arts says that the 1920s saw the development of things like x-rays for teeth, and the establishment of formal guidelines for dental schools. According to the Smithsonian, many employers had dentists on contract and available to see to the dental concerns of any employees.

There was a surprising hairnet campaign

In the 21st century, it's a basic bit of food service and prep hygiene: the hairnet. Absolutely no one wants hair in their food, after all, and this idea is only about 100 years old. For decades, long, sometimes floor-length hair was the height of fashion. That changed in the 1920s, says the Smithsonian, when women started chopping off their long locks for much easier-to-manage bob styles. It was great for women, but it sent some industries — like hairnet manufacturers — into a panic.

That's where Edward Bernays (pictured) comes in. According to The New York Times, Bernays — who was, interestingly, Sigmund Freud's nephew — became known as the "Father of Public Relations," and considered himself a "professional opinion maker." One of his first clients in this pioneering industry was Venida hairnets, who really wanted to make sure the styles of the 1920s weren't going to put them out of business.

To guarantee that, Bernays helped shift the focus of the hairnet and made it one of health, safety, and hygiene. Not only was it an invaluable piece of safety equipment that would keep hair from getting caught in factory machinery, but it was a matter of food hygiene. It might seem like that kind of goes without saying, but his campaign kicked off a new set of laws making hairnets mandatory in kitchens and for restaurant wait staff.

People were introduced to a new way to wash their hair

Today, people who are trying to cut down on how much plastic and packaging they use are discovering shampoo bars, but here's the surprising thing: 100 years ago, it was the norm for washing hair (via Green Queen). According to Holland & Barrett, liquid shampoo wasn't even invented until the 1920s, and instead, people used bars that were essentially cleaning ingredients compressed into a bar. It was used just like soap: Lather between the palms, and massage into the hair and scalp, then rinse. It wasn't just easy to wash your hair, it was easier — as they note, it's much quicker to rinse the lather from a shampoo bar out of hair.

The Independent Pharmacist says that a common alternative was using regular soap for shampoo, but that tended to leave a weird film. It wasn't until 1927 that the German chemist Hans Schwarzkopf invented liquid shampoo. At the time, it was pretty standard to only wash your hair once every few weeks, and it took a little while for the idea of liquid shampoo to make it to the states. (Procter & Gamble didn't make their version until 1934, says New Beauty.)

Bottom line? Great-great-grandma would have loved a trendy shampoo bar, and then wondered why so many people think it's a new thing.

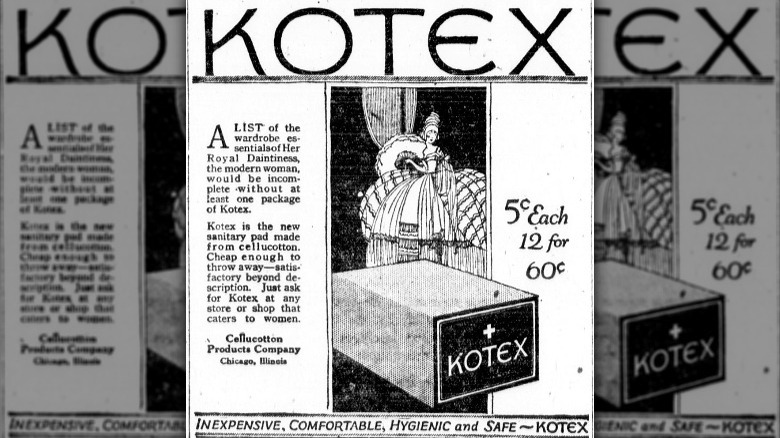

Kotex changed how women dealt with periods

Menstruation has always been a bit of a taboo subject, and that was definitely true in the 1920s — even though women suddenly had access to something that would revolutionize feminine hygiene forever: disposable pads. It's pretty fascinating how the whole thing came about, and according to the Smithsonian, it started with the development of something called Cellucotton. It was originally used for bandages during World War I, and frontline nurses quickly realized they could be used for more than just soaking up the blood from war wounds.

Kotex sold their first sanitary napkins in Chicago in 1919, but there was a huge problem: Female customers didn't want to tell male shop clerks what they needed. What followed was a massive advertising campaign emphasizing Kotex's reputation of being discreet, encouraging women to "Ask for them by name." And ask for them, they did: For the first time, they had what was defined as a "medically sanctioned, 'hygienic' product" to use, and were no longer forced to use whatever home solution — often cloth pads that were washed and reused — they came up with.

As the decade moved on, more and more women turned to using disposable sanitary napkins for the first time. Not only were they more hygienic, but they were much more reliable as well.

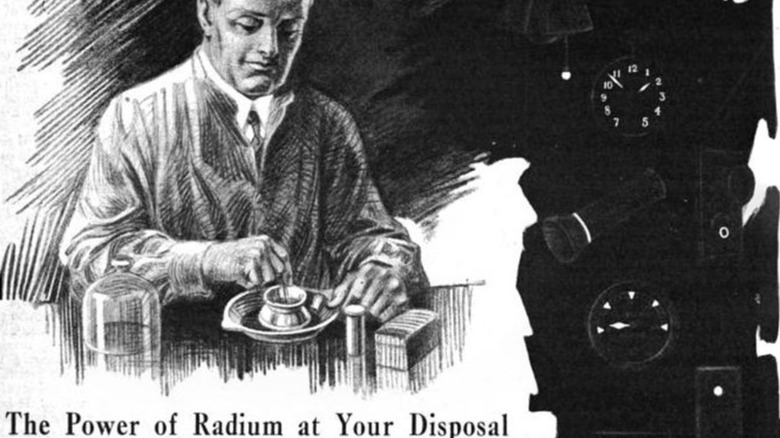

A daily dose of radiation

Good hygiene might help keep a person healthy, but in the 1920s, some products were so dangerous that skipping the typical daily beauty routine just might have been life-saving. It wasn't long after Marie and Pierre Curie discovered radium that people became downright infatuated with the glow-in-the-dark properties of it. It was used for painting watch dials, sure, but according to Georgetown University, it was even used to make a radioactive energy drink — called RadiThor — that was all the rage during the 1920s. Radium — and by extension, radioactivity — found its way into scores of hygiene products, too.

Throughout the 1920s — and into the 1940s — consumers were told that things like radioactive toothpaste, hair care products, and makeup were going to make them bigger, better, and stronger. (Spoiler alert: They didn't.) According to The Washington Post, some of these products packed a massive punch, and surviving examples still set off Geiger counters.

What kind of products? Radium Hand Cleaner boasted that it "Takes Off Everything But the Skin," while Radium Emanation Bath salts could be added to a daily bath solution in order to combat things like insomnia and relieve the pain of arthritis (via the ORAU Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity). There were also products like X-Ray Soap, which was advertised as being able to clean everything from clothes to cars.

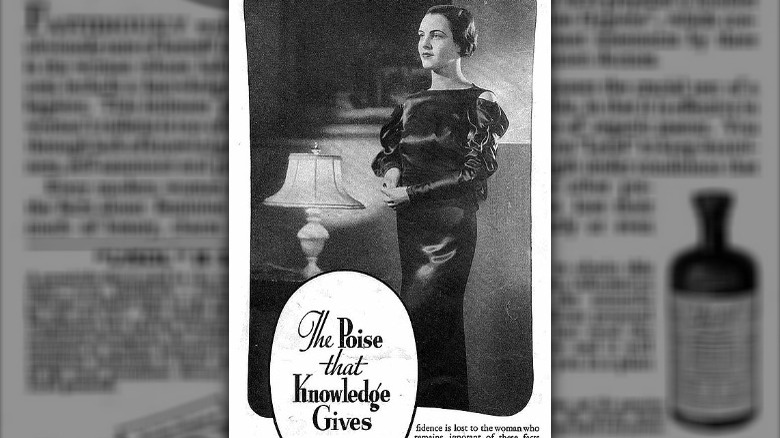

Lysol for feminine hygiene

Just the smell of Lysol is enough to let someone know it's hardcore, and it's probably not something that's going to be kind to the body's soft tissues. Still, 100 years ago, women were using it as a part of their feminine hygiene rituals.

And here's the terrifying thing: According to Mother Jones, doctors knew this wasn't a good idea as early as 1911. That's when they saw 193 women suffer from Lysol poisoning and another five die from the effects of using Lysol — also used for killing ringworm, the flu virus, cholera, and for disinfecting bathrooms — on their lady-parts.

Advertisers throughout the 1920s and even into the 1930s dubbed Lysol as the perfect product to use in the upkeep of "dainty feminine allure," and countless ads warned women that if they didn't spray some Lysol up there to keep fresh and clean, they were definitely going to chase their man away. Ads collected by the Huffington Post 100% blame women's hygiene — or rather, lack thereof — on failed marriages, and promoted it as being dual-purpose. Not only did they claim that Lysol "truly cleanses the vaginal canal," but that it was also an effective birth control. It absolutely wasn't — even though the pre-1953 formula that women were using contained cresol, which definitely burned, definitely caused severe inflammation, and sometimes, made people definitely dead.

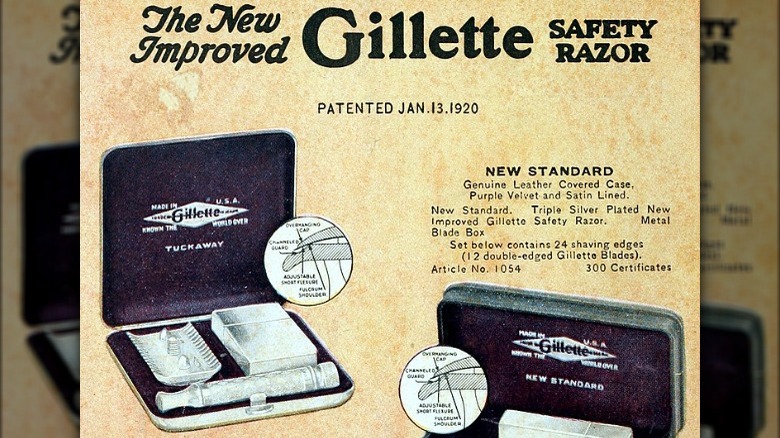

Men could more easily shave at home

By the 1890s, Allure says that the big, bushy beards of the Civil War had given way to a more finely groomed, carefully managed style of facial hair. At the time, though, the only option men had for facial hair hygiene was a straight razor — and given that it was also called a cutthroat razor, well, that pretty much explains what that's all about. It was that way for a long, long time — until about 100 years ago. In 1904, a man with the unlikely but awesome name of King Gillette improved the safety razor by patenting the first disposable one, letting Americans rely less on their barber and more on their own at-home routines.

That was just the start of things, though, and by the 1920s, Jacob Schick made things even more efficient. Schick, says Money Week, was living in Alaska when he decided he was going to overcome some major problems with safety razors. They were hard to reload, and anyone who didn't have water handy was out of luck. So, he invented a dry-shaving motorized razor that was inspired by the same mechanism that reloaded repeating rifles.

Even as men across the country were getting the hang of using these new-fangled razors, Schick introduced something even more revolutionary to the landscape of male grooming: the electric razor, invented in 1928. It took him just two years to sell a million of them, and they've been used to keep skin smooth and injury-free ever since.

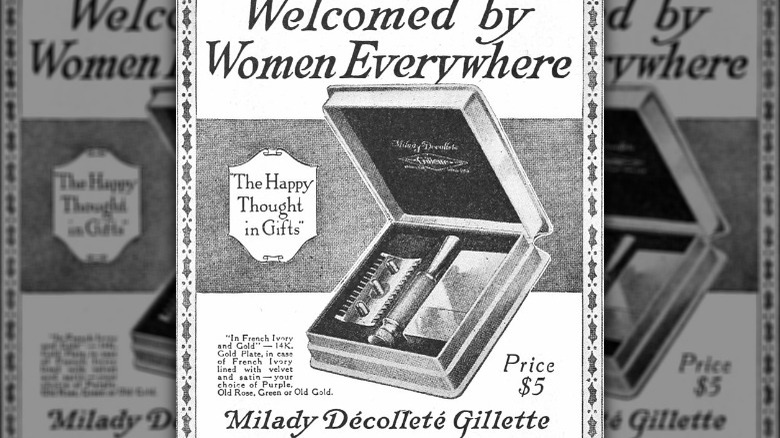

Women were being told armpit and leg hair was awful

Hygiene and personal grooming go hand-in-hand, and 100 years ago, the idea of what hair was acceptable for women to have was changing. According to the Smithsonian, it was around the turn of the century that removing hair became seen as hygienic. It got rid of places for lice, bugs, and bacteria to live, and when it came to body hair, here's where things get dodgy.

Body hair was considered masculine, and starting in the 1920s, something important was happening in women's fashion: dresses were getting shorter, and sleeves were disappearing. Parts of the body that had been covered during the Victorian era were now on display to the world, and companies that were marking newly invented safety razors to men realized they could market razors to women, as long as advertising campaigns made them feel enough shame about the hair growing on their legs and armpits.

Vox found that at the start of the decade, it was so uncommon that when one Kansas girl cut her leg shaving, it made the national news. But it wasn't long before advertisers were condemning underarm and leg hair as one of the biggest embarrassments a woman could suffer, and that meant it wasn't long before many were using all of the razors, blades, and creams that were flooding the market. By the 1940s, Harper's Bazaar declared: "If we were dean of women, we'd levy a demerit on every hairy leg on campus."

Toilet paper goes mainstream

Good hygiene down below is just as important as it is up top, and if 2020 showed the world anything, it's that we can no longer imagine a world without toilet paper. That wasn't the case until incredibly recently, though, and it was only about 100 years ago that America started using purpose-built TP.

Americans, says Mental Floss, spent years wiping their nether-regions with the Sears Roebuck catalog, even after the invention of what modern eyes would see as perfectly acceptable toilet paper. For the most part. Aloe-infused toilet wipes were invented way back in 1857, but they were considered medicinal — advertised as preventing hemorrhoids — until the 1920s. It took a long time to get the public on board with buying a product just for post-movement cleanup, and it took a genius marketing campaign from the Hoberg Paper Company to get people there. In 1928, they introduced a new kind of paper that wasn't medicated — it was soft and would make clean-up a gentle sort of experience, and it was called Charmin.

So, a century ago, Americans were just getting used to using TP on a regular basis, and if that's not weird enough, here's one final footnote on that from History: It wasn't until 1930 that a toilet paper hit the market that could be advertised as "splinter-free." Apparently, the so-called "good old days" weren't as good as we thought.

A clean body needed a clean house

In 2021, Apartment Therapy's Brentnie Daggett spent a week following some of the cleaning routines described in the 1920s-era "Good Housekeeping's Book on The Business of Housekeeping." At a glance, it didn't seem too bad, but once she got into it, it became clear that a 1920s homemaker had her work cut out for her. Every day was filled with scores of chores to keep the house as spic-and-span as the decade's people, and it included things like washing dishes three times a day, dusting, and mopping, but also setting the table and serving meals, plumping pillow and cushions, making sure there were fresh flowers in all the cases, airing out blankets and sheets, polishing mirrors and silverware, and making sure to clean guest bedrooms and bathrooms even if there was no guest in sight.

After a week, the verdict was that it was incredibly exhausting — the meal-making, the laundry, the twice-weekly changing of pillowcases, and the cleaning under things that are better just left unmoved was nearly impossible to keep on top of. It was by Wednesday that she declared: "The novelty of this project had officially worn off."

Bottom line? Hygiene doesn't stop at the person today ... or 100 years ago.