The Most Infamous Black Widow Serial Killers

Female serial killers are as fascinating and as multi-faceted as their male counterparts, but the most famous — or rather, infamous — variety is the so-called black widow. The thing that ties these killers together is target and motive. According to Psychology Today, the black widow serial killer is defined as a woman who had targeted and killed at least three men — usually husbands, fiancés, or boyfriends — in order to advance her own financial status. Many take out insurance policies before administering a fatal dose of poison or a bullet, and sometimes, it's only when someone realizes that they're leaving a trail of victims in their wake that suspicions are aroused.

For some, there's another component to the killing, too: sympathy. People tend to flock to those who have recently lost a loved one in a show of support, and for many black widows, this is a definite bonus.

Here's a weird little tidbit of information: For a long time, those involved in the upper echelons of law enforcement (i.e., men) thought that there was no such thing as a female serial killer. It was believed that women just didn't have what it took to commit murder after murder, and it turned out that was, of course, completely wrong. Ironically, that was a widely accepted belief at the time some of these infamous black widows were killing, enjoying the fruits of their labors, and then moving on to the next target.

Lyda Southard

Lyda Southard, says Time, was born Lyda Trueblood in 1893. The "Southard" part of her name came courtesy of her fifth husband, Paul Vincent Southard. Paul — who quickly divorced his wife after she was arrested for murdering her four previous husbands — probably saw all the pieces of the puzzle fall into place: She had been pushing him to take out a life insurance policy worth around $10,000 when she was arrested.

Lyda was certainly unlucky in love. Husband No. 1 was Robert Dooley, and his official cause of death had been typhoid. Not uncommon for the time, granted, but when "typhoid" also took their child, Robert's brother Edward, William Gordon McHaffie (husband No. 2), Harlan C. Lewis (No. 3), and Edward F. Meyer (No. 4), the life insurance companies that had been paying out started to say, "Hold on just a minute here." By the time law enforcement went to talk with Lyda, she'd already absconded to Hawaii and hooked up with Paul Southard. Investigators exhumed the bodies of the many deceased men and found they had all been killed by arsenic. (Easily obtainable back then, "The Poisoner's Handbook" author Deborah Blum says — via Wired: most flypaper was made with arsenic, and the deadly substance could easily be boiled out of it.)

The New York Times reported Lyda was arrested in 1921. After escaping from prison in 1931, she married husband No. 6 Harry Whitlock. He survived, though, and got the marriage annulled when she was arrested again. She was ultimately released into the custody of her sister in 1941.

Chisako Kakehi

CNN says the trial of black widow serial killer Chisako Kakehi was one of the longest in Japan's history, and it was one of the most terrifying, too — especially to those with elderly relatives. Kakehi was first married in 1969, and that 25-year union came to an end with the death (of natural causes) of her husband in 1994. But it wasn't until 2007 that Kakehi started using a matchmaking agency to be paired with available men ... who would invariably end up dead.

Kakehi's first victim actually survived. Toshiaki Suehiro was poisoned with a cyanide capsule, and would ultimately be taken to the hospital where he just managed to pull through. In 2012, Kakehi was talking marriage to Masanori Honda, who died in a motorcycle accident after mysteriously losing consciousness. Kakehi had been preparing, already seeing a few other men. By 2013, she was talking about marriage again to Minoru Hioki. This time, the cyanide capsule did the job.

A few months after Hioki's death, the black widow married Isao Kakehi. It was only after he died from a massive cardiopulmonary episode that people got suspicious, and when an autopsy turned up cyanide, the new Mrs. Kakehi was arrested. In 2017, CNN says the then-74-year-old was sentenced to death, and in 2021, the Supreme Court of Japan upheld the death penalty ruling.

Judy Buenoano

When Judy Buenoano was sent to Florida's electric chair in 1998, she had the dubious honor of being the first woman to be executed there since 1848 — a time span of exactly 150 years, says the United States District Court Middle District of Florida.

In 1983, Buenoano made an attempt on her fiancé's life. John Gentry had a $500,000 life insurance policy taken out on him, and lucky for him, his exploding car failed to kill him. But the Chicago Tribune says that attempted murder drew attention to Buenoano, and investigators realized the name of their chief suspect meant "Goodyear" in Spanish. It turned out Judy had legally changed her last name from that of her late husband James Goodyear ... and when he had died in 1971, the circumstances had been suspicious.

That kicked off an investigation that confirmed James Goodyear had died of arsenic poisoning. Also dead was their son, Michael — he had first been paralyzed when the arsenic failed to kill him, so Buenoano took him canoeing, where he drowned. In between those two deaths, she was also connected to the death of a boyfriend named Bobby Joe Morris. He had died in 1978 after showing symptoms of arsenic poisoning, and Buenoano collected on not just one, but three insurance policies.

When asked if she had any final words as she was led to the chair, she simply said, "No, sir."

Belle Gunness

It's not entirely clear how many men Belle Gunness murdered, but when law enforcement finally started digging in the pen where she kept her pigs, they found the remains of at least 12 bodies.

According to Cosmopolitan, Gunness's life as a black widow started on July 30, 1900. (Prior to that, she was implicated in the suspicious deaths of two of their children.) That date was pretty significant, because, in an amazing coincidence, it wasn't just the day her husband died of "heart failure," but it was also the only day he had two life insurance policies active at the same time, with one of them about to expire and the other just having started. After his death, Gunness moved, remarried, and killed again: Gunness claimed that man had been reaching for something on her stove when he caught alight and died from his burns. After getting away with that murder too, she got down to real business.

Gunness started by taking out ads in the lonely hearts columns of the country's newspapers. If a man came to meet her, invariably, they disappeared. There's no way to tell how many, but we do know the final one: Andrew Helgelien. When he disappeared, his brother raised the alarm. Gunness decided she needed to do something rash. When her house subsequently burned down, the remains found in the wreckage that were assumed to be hers didn't seem to quite match up with the stature she'd had in life, but law enforcement said, "Good enough."

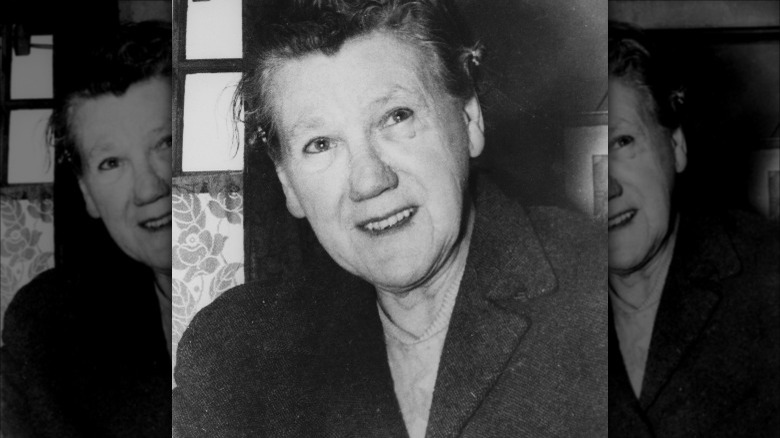

Mary Elizabeth Wilson

Mary Elizabeth Wilson earned herself the nickname "the Merry Widow of Windy Nook," in part because her husbands kept dying, and in part because she was predictably cheery about it. She was, after all, the one killing them. The BBC says that she wasn't shy about it, either, recounting the story of one of her weddings, where a guest commented on the large number of cakes and desserts. When asked what she was going to do with everything that was left over, she answered, "We'll keep them for the funeral."

That's definitely the sort of thing that causes a lot of gossip, and it was the sort of gossip that law enforcement kind of needed to notice. According to the Chronicle Live, they were suspicious enough to exhume two of her four rather short-lived husbands. It was 1957, and Wilson seemed not to take into account recent advances in forensic sciences when she told reporters, "I am not worried about what they are saying. I can go to the blessed sacrament — I am a Catholic — tomorrow."

She may have thought she was going to be forgiven in church, but the law was less forgiving. All four of her husbands were ultimately found to show signs of phosphorus poisoning, which had come from a widely available rat poison (or insecticide). She was found guilty and sentenced to hang, but a last-minute reprieve saw her facing life in prison. She died in 1963.

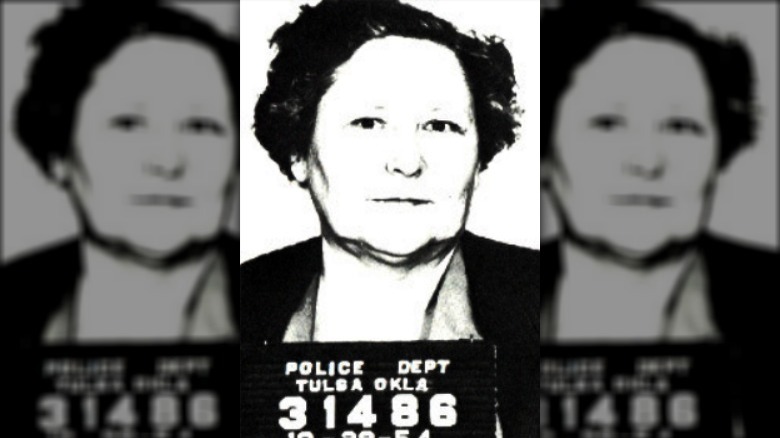

Nannie Doss

Say what you will about her beliefs regarding the sanctity of marriage, Nannie Doss is an undeniably fascinating person. Born Nancy Hazle in 1906, she was known as "Nannie" by the time she could walk. According to Alabama Heritage, that's also about the same time she suffered a head injury she would later blame for her tendency to kill her husbands. Her murderous habits were also blamed, in part, on her voracious appetite for romance novels; it was later suggested that she thought of herself as one of her beloved, fictional femme fatales. Whatever the reason, she started killing while with husband No. 1, Charles Braggs, but he sensed something fishy. After the mysterious deaths of two of their daughters, he left and divorced her.

Doss was married to her second husband for 16 years before killing him — after killing off a few grandchildren in the meantime — with a dose of rat poison. She married No. 3 two days after they met, and by the time he died with symptoms suspiciously like those caused by poisoning, she'd made sure everyone in town liked her more than him. The house he left to his sister burned down as Doss left, Doss' mother-in-law and sister both died suddenly ... while she was with them. In due time, she remarried and took care of husband No. 4 — with more rat poison.

When No. 5, Samuel Doss, died suddenly, an autopsy turned up traces of arsenic in his stomach. After Nannie Doss confessed to police and her other former husbands were exhumed, the evidence they found was enough to put her away for life.

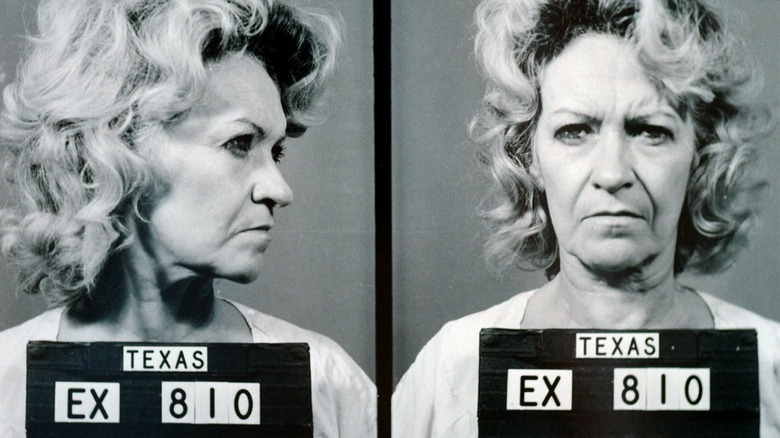

Betty Lou Beets

Things started going sideways for Betty Lou Beets in 1985, when the bodies of both her fourth and fifth husbands, Doyle Wayne Barker and Jimmy Don Beets, respectively, were found buried on her property. Both men had been shot and killed, and the Clark County Prosecutor says that it was the murder of Beets that got her the death penalty.

The verdict came in spite of claims that Beets had been acting in self-defense and had been physically abused by both men. According to the Crime Museum, there was a little more to it. She got married for the first time when she was just 15, and that rocky relationship ended in 1969. The next year, she married husband No. 2, a marriage that lasted just two years and ended in divorce when she shot and wounded him after he broke her nose. She married No. 3 in 1978 and tried to kill him — with help from her car — about a year later. That was the same year she married Doyle Wayne Baker.

When Betty Lou Beets was executed in 2000, CBS News said her death was witnessed by the sons of the two men she'd killed, including Jamie Beets, son of husband No. 5 Jimmy Don. Jamie recalled, "I just kind of focused on my dad. I seen my dad's face. I knew that he was smiling and it was over now."

Betty Neumar

When Betty Neumar died in 2011, she was 79 years old. The official cause was cancer, but according to Cleveland, she was so reviled by the families of her long-dead husbands that some didn't even believe she was dead.

Neumar had quite the track record of husbands with suspicious deaths, dating right back to No. 1. That was Clarence Malone, although they had been divorced for nearly two decades when he was shot and killed in 1970, while at work. Long before, Neumar had already moved on to No. 2: She had been married to James Flynn when he died in 1955, and she told two entirely different stories about his death. In one version, he froze to death in his truck, and in the other, he was shot and killed.

She was arguing with No. 3 when he was killed, although she was able to convince law enforcement that he'd shot himself. Evidence collected at the time — 1967 — suggested he'd been shot twice. No. 4 Harold Gentry died in 1986, and there was no doubt that it hadn't been from natural causes: He was shot six times. (It was his death that finally got her arrested and charged not with murder, but with "solicitation to commit murder" — and even that charge took two decades to stick). No. 5 died from a sudden onset of sepsis. He was immediately cremated, but that didn't stop investigators from noting that blood poisoning can present symptoms similar to poisoning with arsenic. Neumar maintained her innocence in all cases.

Mary Ann Cotton

History Collection says that Mary Ann Cotton was in the midst of death and tragedy almost from the day she was born, but to be fair, that was in 1834, and the same thing could be said of almost all Victorian Britons. In spite of that early tragedy, she seemed to have a promising career ahead of her, first as a nurse, then a dressmaker. And here's where things get a little shady, because documentation wasn't the most reliable at the time. By 1864, six of her nine children were dead. Did she kill some or all of them? Quite possibly. But the following year, she committed her first known murder.

That was the murder of her first husband, William Mowbray. She collected on his insurance policy, and by the time she married No. 2, George Ward, two more of her children were dead. Ward died in 1866. Her next husband, James Robinson, booted her out of the house when he caught her stealing money and pawning his possessions.

Next was the widower Frederick Cotton, who died mysteriously in 1871, then Joseph Nattrass, who died in 1872. More and more of her children and stepchildren died along the way, and it wasn't until she told a parish official that a current stepson would soon "go like all the rest," that the deaths surrounding her started to be investigated in earnest. Mary Ann Cotton went on trial in March of 1873, was found guilty, and hanged the same month.

Catherine Flannagan and Margaret Higgins

Catherine Flannagan (right) and Margaret Higgins were sisters living in the slums of Victorian-era Liverpool. At that time, one of the ultimate insults of a life of poverty was considered the indignity of a pauper's burial. In order to give even the poorest of England's residents a chance at a decent burial, so-called "burial societies" were set up. It was basically insurance: Customers would pay in a few pence at a time, and when someone died, the money in the accounts would be used to pay for their funeral.

Flannagan and Higgins realized that if enough people close to them who had joined a burial society died — and the two of them then kept their relatives' funerals cheap — they could rake in scores of cash. Criminal lawyer and historian Angela Brabin says (via History Today/Index Articles) that while it was the murder of Margaret's husband, Thomas Higgins, that eventually got the sisters hanged, their murder-for-money scheme went way beyond that.

Thomas's daughter, Mary, died about a month after he and Margaret were married, and when he also died — in spite of being in the peak of health — his brother pushed for an investigation. Three bodies — including Flannagan's son, Mary Higgins, and another young lodger — were exhumed, examined, and found to have died from arsenic overdoses. The recipients of their insurance policies and burial society money? Catherine Flannagan and Margaret Higgins. According to the BBC, it's estimated they killed around 17 people before their 1884 execution.