Nobel Prizes Given Out To Undeserving Winners

Typically, when you win a Nobel Prize, it's a well-deserved honor proving that you're the absolute best in your field. As Alfred Nobel wrote in his will, the prize is for "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind."

But sometimes after people win a Nobel, time proves they didn't deserve it. Other times, the winners make no sense immediately, like the Nobel Committee just awarded the first name they thought of, qualified or not. Here are some people who truly put the "no" in "Nobel."

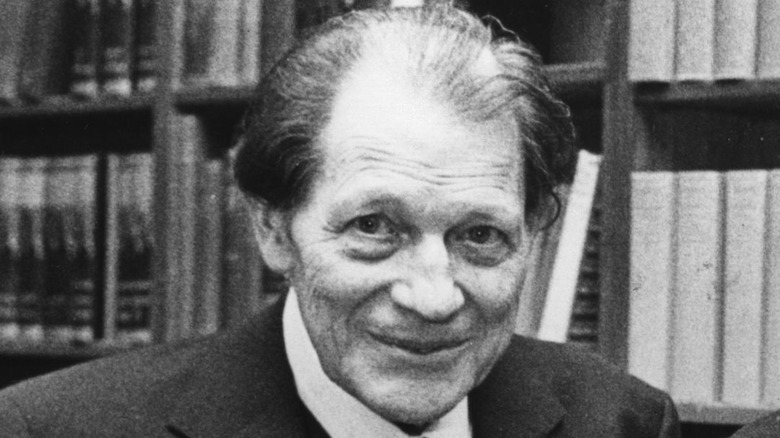

1949: Egas Moniz, Medicine

When you invent one of the most maligned surgical procedures of all time, it's pretty hard to justify getting rewarded for it in any way. And yet that's exactly what the Nobel Committee did in 1949, handing Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz the Nobel Prize for medicine, because he invented the lobotomy.

As the BBC recapped, in 1935 Moniz theorized that patients with "obsessive behavior" had issues deriving from certain areas of the brain. So he, as he explained in his creatively titled monograph "How I Came to Perform Frontal Leucotomy," "sever[ed] the connecting fibres of the neurons in activity." In short, he drilled a hole in a patient's skull, rooted around with a long needle called a leucotome, and disconnected the frontal lobe from the brain, like cutting the red wire to diffuse a bomb. This bit of brain-snipping became shockingly popular, and 14 years later, Moniz received the Nobel Prize.

The problem, as everyone is well aware by now, is that lobotomies are terrible, and do nothing to help the patients, but everything to stupefy them. Worse, as the Nobel website itself reports, there were significant hints — almost from the get-go — that poking, prodding, and slicing a brain isn't a terrific idea.

By the end of the 1930s, patients' lobotomies seemed to result in their developing negative personalities. Researcher Gosta Rylander studied many a lobotomy patient and their loved ones — some of what they told him was just plain heartbreaking (via "The Triune Brain in Evolution," by P.D. MacLean. One woman said of her lobotomized daughter, "She is ... a different person. She is with me in body but her soul is in some way lost." A friend of another patient said, "I am living now with another person. She is shallow in some way." And as Rylander himself reported, "Some of my patients have lost the ability to dream."

1973: Henry Kissinger, Peace

For many, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger has absolutely nothing to do with peace. He's seen by many as a war criminal, someone who allegedly orchestrated numerous secret bombings during the Vietnam War. As writer Christopher Hitchens put it in his book, "The Trial of Henry Kissinger," the man should be arrested "for war crimes, for crimes against humanity, and for offenses against common or customary or international law, including conspiracy to commit murder, kidnap, and torture." Need examples? It ranges from allegedly ordering a secret bombing in Cambodia that killed countless innocents, to aiding Chilean general Augusto Pinochet in murdering thousands of dissidents during a political coup (both mentioned by The New Yorker).

And yet, Kissinger has a Nobel Prize. For peace. That's because, while most of what people hate the man for has never been proven, it can be proven that he worked toward a ceasefire in the Vietnam War, something he achieved in January 1973. Later that year, he received the Peace Prize for those efforts, which was quickly undermined by the ceasefire not working. (The war didn't end until 1975.) Plus, at the same time Kissinger was negotiating this failed cease-fire, he was also organizing raids and bombings on Vietnam's capital, Hanoi (as reported by the Nobel site). You can practically smell the cognitive dissonance.

To Kissinger's credit, even he recognized how bad a look his winning a peace prize was. According to The Washington Post, he not only refused to accept it in person, he even attempted to give back his medal. This failed, as the Nobel Committee never revokes prizes ...though perhaps they should start.

1912: Nils Gustaf Dalén, Physics

Winning the Nobel Prize for physics typically means you've revolutionized your field somehow. Then, you've got Nils Gustaf Dalen, who won for minor improvements in how lighthouses work (via the Nobel Prize website).

In 1912, Dalen invented the Solventil, a solar valve that regulated how much gaslight was used in a lighthouse (via Britannica). With it, you could shut down a beacon when the sun rises, and automatically turn it back on when night falls. That's certainly a good thing — using less energy and resources is always welcome. But is it Nobel-worthy? Almost certainly, no.

As Burton Feldman wrote in his book, "The Nobel Prize: A History of Genius, Controversy, and Prestige," "This remains the least impressive award in any science category ... it seems to have happened because of the academy's deadlock over far more impressive candidates such as [Max] Planck."

As it turns out, Feldman wasn't too far from the truth. As revealed in 1977 (according to Francis Leroy's book, "A Century of Nobel Prize Recipients: Chemistry, Physics, and Medicine"), the committee's original idea was to give that year's prize to both Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla. Problem was, the two were in the middle of a financial feud and Tesla flat-out refused to share the award. Rather than give it to one or the other, the committee chose to forget both of them and awarded a guy who invented a decent lifehack for old-time lighthouses. That'll show those squabbling geniuses.

1994: Yasser Arafat, Peace

Whether you consider Yasser Arafat a violent terrorist or a freedom fighter largely depends on where you stand on the Palestine-Israel debate and conflict. Either way, however, it's hard to deny that Arafat's 1994 Nobel Peace Prize, given out for working towards peace in the Middle East, as per the Nobel Prize website, looks less impressive after more than 20 years of almost no Middle East peace at all.

According to History, in 1993, Arafat got together with Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres to work out a solution for the seemingly endless Israeli-Palestinian war. The result was the Oslo Accords, in which both sides exchanged handshakes (as famously moderated by President Bill Clinton in the picture above) and exchanged letters acknowledging the legitimacy of each others' territories (via the State Department). For that, all three received a share of the following year's Nobel Peace Prize.

Almost immediately, however, very non-peaceful events transpired — as reported by the Los Angeles Times, around the time of the award ceremony, an Israeli soldier who had been abducted by "Islamic militants" was shot to death during an Israeli rescue attempt. Just like that, Israeli-Palestine relations got thrown for a loop, and they haven't really recovered since.

So you may think Arafat uses terrorist tactics to force Palestine on the world. Or you may think he's in the right and is simply doing whatever it takes to win his people freedom and legitimacy. Regardless, you have to admit: a peace prize based on a peaceful agreement that almost immediately turned to violence isn't the best look.

1997: Dario Fo, Literature

Imagine winning a Nobel Prize not because you're incredible at what you do, but because the committee wanted to surprise everyone. That's basically what happened with Dario Fo in 1997. A long-time playwright and comic performer in Italy, Fo wasn't at all bad at what he did. He was actually pretty popular. According to the London Times, at one point he drew 16,000 people to see him perform a one-man show. So he'd clearly have a stranglehold on the Nobel Prize if it were a popularity contest. But, y'know, it's not.

Fo was up against heavy competition for the Nobel that year — legendary writers like Salman Rushdie and Arthur Miller. Fo, meanwhile, was apparently best known for a still-not-very-well-known 1970 play called "The Accidental Death of an Anarchist" — not exactly "Death of a Salesman" or "The Satanic Verses." He's mostly seen as a "brilliantly talented clown," to quote one critic. So why did he win?

Well, according to Fo's own publicist, Michael Earley, it may have been because doing so would've be unpredictable. Earley claims, in the aforementioned Times interview, that the committee told him they weren't voting for either Rushdie or Miller because it would be "too predictable, too popular." And so, Batman and Superman lost to the literary equivalent of Matter-Eater Lad, just so the Nobel Committee could look at the world and say, "gotcha!"

1958: Joshua Lederberg, Medicine

Esther Lederberg was an amazing microbiologist, but she doesn't have a Nobel Prize to her name. Her husband, Joshua Lederberg, does, though he did much less to deserve the award. However, it was 1958 and Esther was a woman. Thus her husband got the glory, and she got squat.

In 1958, Esther and Joshua Lederberg were working at the University of Wisconsin, where she made more than one major medical breakthrough, according to Stanford Magazine. First, she discovered the e-coli-centric virus lambda bacteriophage, paving the way for the study of other, more complex viruses. Then, she and her husband developed a technique called replica plating, where you move bacteria from plate to plate to show where mutations like antibacterial resistance occur. This ability to break down bacteria's life cycle had huge implications on how to develop innovations like antibacterial medicine, which you might recognize as something that's helped keep tons of people alive.

Esther spearheaded the research, even using the powder puff from her compact to make the initial bacterial movements. So the Nobel Committee acknowledged the real MVPs ... who were anyone but her, apparently. Her husband shared the Nobel with two other male scientists — as the committee noted, "bacterial genetics has been developed, primarily through the efforts of [Joshua] Lederberg and his co-workers, into an extensive research field in recent years." You'll notice not a single reference to "wife" or "Esther" anywhere.

Did Joshua Lederberg deserve a Nobel? Perhaps, but his wife deserved it more. Not only did she contribute equally, and possibly more so than Joshua, to developing replica plating, she also revolutionized viral research. Joshua either should've won with her, or she should've won alone. But that's what happens when a woman goes up against the '50s.

2009: Barack Obama, Peace

Barack Obama isn't the first American president to win a Nobel Peace Prize. Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson won while in office, and Jimmy Carter won long after he left Washington. But Obama is the first to win for basically no reason whatsoever. Regardless of whether you're Team GoBama or NoBama, it's hard to deny he won the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize after doing virtually nothing.

In 2008, Obama went from obscure one-term senator to president of the United States. A mere nine months later, the Nobel Committee decided he had done enough to warrant being a beacon of peace — despite sending 30,000 extra troops to Afghanistan at roughly the same time he was to be honored, according to The Washington Post. As the committee put it, he was rewarded "for his extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples." Remember, he had been in office for less than a year, and the Nobel people insisted he did all this. More likely, he was rewarded for simply not being his predecessor, George W. Bush.

Others agree. The New York Times opined that the award "seemed a kind of prayer and encouragement ...for future endeavor and more consensual American leadership." Republicans claimed he won the award mainly because of his "star power," a sentiment even some Democrats agreed with, according to the Times. Even Obama himself was shocked that he had won, saying during a Rose Garden speech, "To be honest, I do not feel that I deserve to be in the company of so many of the transformative figures who have been honored by this prize." He may have simply been humbled by the honor, but let's face it — he also stumbled upon the truth.

1974: Harry Martinson, Literature

In 1974, a poet/novelist named Harry Martinson won the Nobel Prize for literature, though it's probably more appropriate to say he won for living in the right country, and being buddies with the right people.

It wasn't that Martinson was a lousy writer — by most accounts, he was actually quite good. As the reference book "World Authors, 1950-1970" put it, he was "perhaps the most sensitive and original of the poets of his generation ... distinguished above all by the extreme precision of his language" (via the New York Times). The problem with making him a Nobel laureate is that, outside of his native Sweden, few people have heard of him, as the Times noted. Outside of his 1956 epic poem "Aniara," about a spaceship headed to Mars that misses its target and drifts off into space seemingly forever, you pretty much have to go to Sweden to learn anything about the guy who won an international award for his work.

But maybe you think that doesn't matter. After all, plenty of transcendent talents don't achieve worldwide recognition. And that's true. So here's another reason he probably didn't deserve the Nobel: he voted for the Nobel. Yep, in 1949, after publishing his novel, "The Road," Martinson was elected to the committee. While it can't be proven if he voted for himself or not, there's a real good chance he at least got votes because, to the committee, he was "one of them."

1992: Rigoberta Menchú, Peace

On the surface, Rigoberta Menchu seems like a perfect candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize. As the Nobel site put it, she won in 1992 "for her struggle for social justice and ethno-cultural reconciliation based on respect for the rights of indigenous peoples." A champion of Indian peasant rights and a resistor of Guatemalan oppression, her 1983 book, "I, Roberta Menchu," brought her and her people's plight to a worldwide stage, and she's been championing Indian peasants and their right to live ever since.

So what could possibly be wrong with honoring someone like that? How about a better-than-good possibility that her memoirs were semi-fictionalized propaganda?

While there's no concrete proof, a reporter for the New York Times named David Stoll visited Quiche, Guatemala, to speak with locals about the kind of violence Menchu spoke of. He came away with a vastly different picture from what Menchu painted, one where the resistance and the Guatemalan army were almost equally bad. As one villager put it, "Both the guerrillas and the army like trouble. But we're a civilian population; we just want to cultivate our maize." Another said, "They're using us as a shield because, when there are confrontations, the army sends patrollers to fight. And when the guerrillas [the resistance] attack, they bring civilians to fight with other civilians." In addition, Stoll found a savvy citizenry who knew how to use elections and the court systems to their advantage, as opposed to the helpless populace who could only fight with the guerrillas by their side whom Menchu documented in her book.

Stoll's extensive research, if true, seems to paint a picture the Nobel Committee would not want to hear — Menchu and her guerrilla army were just as violent as the Guatemalan army, but she won a peace prize by painting her side as benevolent Jedi, when they may have been more like a second Sith all along.

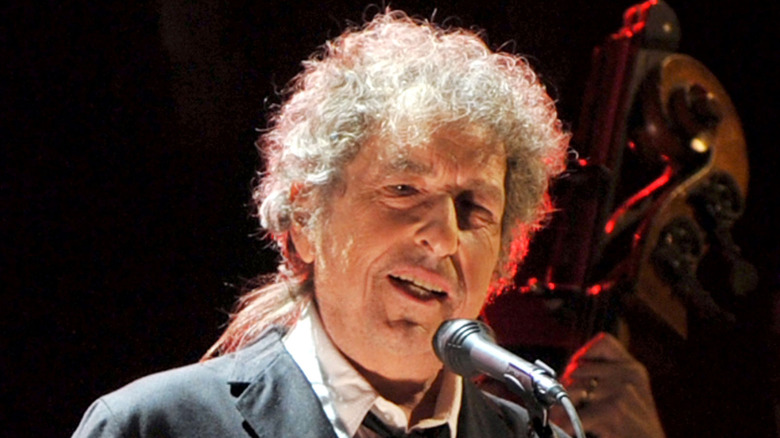

2016: Bob Dylan, Literature

Obviously, Bob Dylan is an amazing musician, and his lyrics are among the most unique in music history. However, the Nobel Committee awarding Dylan the 2016 Nobel Prize for literature — when what he does is decidedly not — makes almost as much sense as "It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry."

According to the Nobel Committee, Dylan won because "his influence on contemporary music is profound, and he is the object of a steady stream of secondary literature." But you know who doesn't get why the committee made such a big deal about him? Dylan himself, who barely acknowledged the award for months after his win, and refused to give his required lecture until almost the very last second, as per The New Yorker. When he finally did, he arrived in a black hoodie (according to The Local Sweden) and gave a speech that spoke of literature like "Moby Dick." Problem is, according to The Atlantic, his speech almost certainly plagiarized the Sparknotes summary of Herman Melville's book. Clearly, he cared about the honor just that much.

In one of the more original parts of his speech, he mentions that "songs are unlike literature. They're meant to be sung, not read. The words in Shakespeare's plays were meant to be acted on the stage. Just as lyrics in songs are meant to be sung, not read on a page." That's basically Dylan's very Dylanesque way of saying "this is ridiculous. A lit prize? Really?"

But even if you think music can be literature, Dylan has proven time and again that he's not interested in writing that way. As The Guardian points out, Dylan went out of his way to craft vague, random lyrics "to escape from people who thought they understood him." In the 2005 Martin Scorsese documentary, "No Direction Home," Dylan outright admitted he didn't have a message. To him, the best art is meaningless — almost as meaningless as a Nobel Prize.