The Most Infamous Serial Killer Nurses

It's safe to say that there are not many people who enjoy going to the hospital. There are not many who look forward to retirement in a nursing home or assisted living facility, either, and there are definitely not many who want to spend their final days in a clinical environment surrounded by strangers taking care of their most basic biological functions. That's a super depressing way to start, and it's only going to get worse.

Patricia Pearson is the author of "When She Was Bad: How and Why Women Get Away with Murder," and she estimates (via The Walrus) that in the decades since 1970, more than 2,600 nursing home and hospital deaths can be associated with the work of a serial killer. Those same decades have seen the arrest and conviction of around 90 of these killers, and that's more than a few each year.

Some kill because they like it, some because they can, and some believe they're doing the patient a favor by putting an end to their suffering. Regardless of motive, it can be incredibly hard to prove a nurse (or doctor) is killing by giving the wrong meds, incorrect dosing, or even just sort of administering a lethal dose of something seemingly harmless — like insulin. She says: "Like the red-light district and the lonely highway, institutional care settings are prime hunting grounds for the modern serial killer." Serial killers like these.

Joan Vila Dilmé

Joan Vila Dilmé isn't just a serial killer, he has the dubious honor of being the most prolific serial killer in Spain. His crimes first came to light in 2010, and here's the most horrifying thing: He didn't kill over a span of decades. His 11 victims — all between the ages of 80 and 96 — died between August 29, 2009 and October 17, 2010. The frequency of his kills had been steadily increasing, with five people dying in the month before his capture.

Questions started to be asked about the geriatric nurse from the Girona province in Catalonia after an 85-year-old woman was discovered to have died with chemical burns in her esophagus. When law enforcement started pressing staff, Vila confessed to having forced the woman to drink a syringe full of cleaning fluid. Further investigations into the people who died on Vila's watch uncovered more and more victims, killed first by insulin overdoses, and then, by the forced ingestion of cleaning chemicals.

Dr. Miguel A. Soria Verde of the University of Barcelona took an in-depth look at the case and wrote (via ResearchGate) that Vila isn't precisely considered an "angel of death," in spite of his insistence that he killed because he wanted to end his patients' suffering. He did quite the opposite, killing in a way that maximized suffering — a fact that was taken into account when he was sentenced to 127.5 years in prison.

Genene Jones

Texas Monthly says that it was 1981 when a pediatric nurse named Suzanna Maldonado went to her bosses at the Bexar County Hospital with concerns that had been circulating for a while. Children in the ICU weren't just dying, they were dying when one nurse in particular was working — and there were so many that it started to be known as the Death Shift.

When investigations finally started in earnest, it was found that there was no explanation for the high number of fatalities on Genene Jones's shift — but there was no proof that she was to blame, either, and it was possible to argue that children were just succumbing to bizarre complications. A lot. Amid the upheaval at Bexar, Jones quit and went to work with a pediatrician in another part of Texas. The high death rate went with her, and when a small-town pediatrician's office was suddenly seeing one sick and dying child after the other, it was a red flag that couldn't be overlooked anymore.

Jones's conviction for the death of one child and the attempted murder of another came in 1984, and according to USA Today, there was — at the time — a mandatory release law that very nearly saw her walk free in 2018. New evidence was brought, and five new murder charges were filed, though, and she was given another life sentence. It's unknown how many children she killed, but the Bexar County District Attorney's office suspects the number is somewhere around 60.

Elizabeth Wettlaufer

The idea of a serial killer preying on the most vulnerable demographic is a terrifying thing, and according to what Elizabeth Wettlaufer said (via CBC) after her arrest, she definitely had a preferred victim type: "Every patient I ever picked had some dementia and that was part of what became my criteria. If they had dementia, they couldn't report, or if they reported, they wouldn't have been believed."

Possibly even more terrifying is that no one had even suspected there was anything foul afoot, and it was only after she confessed her crimes to a psychiatrist at Toronto's Centre for Addiction and Mental Health that she was arrested and the deaths she'd been responsible for were finally investigated (via Global News). Worse? She had confessed multiple times before, to her then-girlfriend in 2007, then to another care worker, her pastor, an ex-boyfriend, a lawyer, and her Narcotics Anonymous sponsor. It wasn't until 2016 that someone did something about it, and convinced her to give herself over to law enforcement.

It was later found that Wettlaufer's preferred method of killing — with an overdose of insulin — wasn't just hard to detect in an autopsy, but it was pretty easy to miss from a drug control standpoint, as well. She later testified that she tried killing "just to see what happens," then used it as a way to relieve stress. She was ultimately found guilty and given a life sentence.

Jane Toppan

Jane Toppan, says the New England Historical Society, had a horrible start to life. Born to a poor immigrant family sometime in the mid-1850s, she wasn't yet a teen when she was dropped off at an orphanage. After, that is, her mother succumbed to tuberculosis, and her father — driven mad with grief — sewed his own eyes shut.

Raised in a well-to-do home as an indentured servant, she eventually ended up at the Cambridge Hospital, where she trained to become a nurse. Known as "Jolly Jane" for her bubbly nature, it was early on in her career that her supervisors became concerned by the fact that she seemed to like autopsies a little too much. That's about the same time she started experimenting with drugging patients and then getting in bed with them as they fell unconscious, a pastime that escalated into murder.

Victims included multiple landlords, friends, a foster sister, housekeepers, would-be lovers who scorned her... it's a long list. Her go-to method was poisoning with morphine, strychnine, or atropine, and after she was arrested, law enforcement found that her motives were just as varied. Sometimes people annoyed her, sometimes it was for the money, and when she killed her patients, she laid next to them for a "sexual thrill." In 1902, she confessed that she'd killed somewhere between 31 and 100 people. Declared insane, she spent the next 36 years at the Taunton State Hospital and died in 1938.

Austria's Angels of Death

In 2008, the upcoming release of the women dubbed "Austria's 'Angels of death'" was met with shock and outrage. It's no wonder — their crimes, says NBC, were the stuff of horror movies, and took place between 1983 and 1989.

That's when nurses' aides Waltraud Wagner, Irene Leidolf, and accomplices Maria Gruber and Stefanija Mayer killed at least 20 (and possibly as many as 42, says The Guardian) of their patients — all of whom were elderly. The method of execution was grisly: After filling their lungs with water, patients were injected with tranquilizers and insulin. Prosecutors said their victims faced "terrible suffering" before dying, so it's not surprising that when it was announced Wagner and Leidolf were going to be released in 2008, the Austrian public was not on board.

Gruber and Mayer had been convicted on lesser charges than their counterparts, and had already been released and given new identities. The entire case was causing many to give their justice system — with a policy of a maximum 15-year-sentence — a second look. Still, Leidolf and Wagner had apparently been enjoying a "prerelease program" where they were allowed to head out into nearby cities for day trips, while one woman summed the whole thing up like this: "... it's not fair to their victims' loved ones when a killer can look forward to a nice life outside prison."

Charles Cullen

It happens a lot: Someone is arrested for a series of crimes, and those closest to them say they suspected nothing. It's kind of a trope at this point, but according to The New York Times, it doesn't apply to Charles Cullen. Cullen's life was described as "a trail of signal flares," including his four stays in psychiatric facilities, and his tendency to spend his nights chasing cats.

Still, after graduating from nursing school in 1987, he got his first job in the field — and then, over the following decades, he went from job to job. The reasons for his terminations were always a little iffy, and it wasn't until 1993 that he was accused of murder for the first time. The accuser was the son of the victim, a woman who died after a nurse gave her a lethal dose of a chemical called digoxin. Cullen was pointed out as the nurse in question, but when the victim's autopsy didn't find anything suspicious, he was allowed to keep doing what he was doing.

By the time Cullen was finally arrested, he had been working as a nurse for an almost unthinkable 16 years. He confessed to killing between 10 and 20 people at each one of his many, many jobs, and CNN says that when the judge gave victims' families the chance to confront him in court, it took four hours. He was given 11 life sentences and ruled eligible for parole after serving 397 years.

Richard Angelo

Richard Angelo wasn't just a nurse, says ThoughtCo., he was also a volunteer firefighter and a longtime member of the Scouts. It makes sense, then, that his motivation for assaulting and poisoning patients under his care was so that he could rush in, appear to save the day, and be lauded for his heroism. After graduating from nursing school in 1985 and eventually settled down into Long Island's Good Samaritan Hospital. It was there that he decided to start killing patients so he could resuscitate them, and it didn't work a lot of the time. During his stint at Good Samaritan, 37 of his patients had medical emergencies while he was on duty, and only 12 survived.

Then, in 1987, one of the survivors was able to identify Angelo as the nurse who had given him a mysterious injection. Gerolamo Kucich testified (via The New York Times) that Angelo had come into his room and asked him how he was doing. He continued: "I say, not bad. He opened up his coat and pulled out something that looked like a pen. Then he say, 'Now, you are going to feel much better.' ... I became dead. I couldn't move my muscles."

Kucich's death was averted by another nurse, and others who had died under Angelo's care were exhumed, tested, and found to have traces of the deadly cocktail still in their bodies. Angelo was found guilty of a slew of charges and sentenced to 61 years to life.

Orville Lynn Majors

It's unknown how many people Orville Lynn Majors killed, but according to the BBC, he was convicted of the murders of six, but was believed to have killed up to 130. (To stress just how devastating that number is, 147 total people died at the hospital during the time he worked there — and only 17 weren't thought to be associated with him.) The murders that were definitively connected to him occurred at the Vermillion County Hospital in Illinois, where he worked from 1993 to 1995. During that period, The New York Times says the death rate in Majors' unit increased from 31 or fewer per year to 120 per year, so needless to say, it was pretty obvious that something was up. Especially, they note, when four patients died suddenly on the same day.

Investigations found that patients seemed to die when Majors was with them, and it was later found that he used a cocktail of potassium chloride and epinephrine to stop patients' hearts. Victims' family members testified that sometimes, he even administered the injections while they were standing there, leaving their loved ones to die before them.

Majors was found guilty and sentenced to 360 years in jail, but he would serve only a fraction of that time. He died in 2017 after suffering from undisclosed heart issues.

Niels Hogel

Niels Hogel was a German nurse, and like many serial killers in the medical field, it's uncertain just how many people he killed. The Local says that while he was originally convicted for the deaths of six people after being arrested in 2005, he was back in court in 2018. Now, he was being charged with 100 deaths, and investigators added that they thought the actual body count was closer to 200 — something which would never be proven, with the cremation of some of his suspected victims. In 2019, NPR reported that he had been found guilty on 85 counts and was sentenced to spend the rest of his life behind bars.

Hogel's victims were as diverse as his methods. Ranging in age from 34 all the way up to 96, they were killed after being injected with "a variety of drugs." There were so many that while Hogel admitted to some and could give pretty precise details, there were others he didn't remember too much about. As to why, he explained that sometimes he had just been bored, sometimes he needed to kill as a stress reliever, and sometimes, he just wanted the glory of saving a life — even if he'd tried to kill that person first.

His sentencing was bittersweet for many: While they knew he was behind bars, others needed to come to terms with the fact that they would never know for sure whether or not their loved ones were among his victims.

Beverley Allitt

Beverley Allitt is one of a number of serial killers to be given the moniker "Angel of Death," and according to Biography, she has the dubious honor of being one of the UK's most infamous killers.

After starting off going from doctor to doctor and hospital to hospital for her own treatment — most of which was unnecessary and done because she liked the attention she got after surgery — Allitt quickly became well-known throughout local medical circles for what was believed to be her Munchausen's syndrome. (That, says the NHS, is when a person makes themselves sick or pretends to be sick in order to get the attention they crave.) When looking for medical treatment for herself wasn't gratifying enough anymore, she decided to become a nurse.

After struggling through her nursing courses, she was taken on by an outrageously understaffed hospital in 1991. It was there that she claimed her first victim, a 7-month-old who was hospitalized with a chest infection. Her second — an 11-year-old with cerebral palsy — died within weeks, and other suspicious deaths followed. Autopsies and causes of death raised no alarms, though, and by the time she was charged in late 1991, it was for four deaths and 11 attempted murders. She was ultimately convicted and sentenced to 13 life terms (via the Independent).

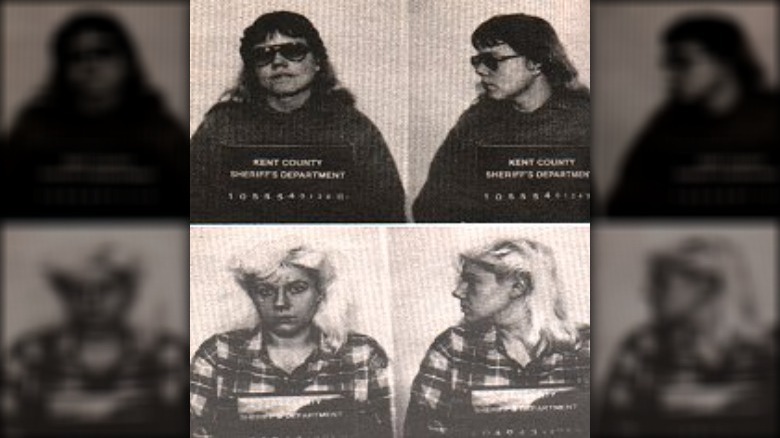

Gwendolyn Graham and Cathy Wood

Serial killers are typically a one-person show, but occasionally, they come in pairs. That was the case with Gwendolyn Graham (top) and Cathy Wood (bottom), a pair of nurses' aides who were working in a Michigan nursing home when they decided to kill — a move that Wood later said (via Oxygen) came when the then-lovers decided they wanted "something that would bind [them] together forever."

Their diabolical plan kicked off in 1985, when Marguerite Chambers entered the Alpine Manor nursing home. Although her family noticed that she seemed to often be dirty and frightened about something, reassurances from the staff were quick to come. Chambers passed away early in 1987, and it later came out that Graham had suffocated her with a washcloth — twice. When she survived the first attempt on her life, Graham returned to finish the job before taking Wood back to her house with an explanation that it was "a release."

Although Wood was originally thought to be a bit of a bystander in the whole thing, it later came out that she and Graham had planned to murder five people, selected on the basis of their first initial. They'd wanted their victims' initials to spell "MURDER" when combined, and Marguerite was the first.

After their arrests, Graham was sentenced to life and Wood to 20-40 years. According to People, she was released in 2019 after almost 30 years — and after inspiring an episode of "American Horror Story: Roanoke."

Kimberly Saenz

In 2018, there was a major problem at Lufkin, Texas's DaVita Dialysis Center. Patients were going in for their regular dialysis treatment, and then, they were suffering massive heart attacks and dying. The scale was unprecedented, and according to Oxygen, they saw 30 incidents in the month of April alone.

They knew early that something was horribly wrong, and consultants were sent in on April 2 to investigate the two deaths that had already happened. It wasn't until April 28, though, that two patients reported seeing a nurse named Kimberly Saenz prepping a bleach cleaning solution, and then not sanitizing the floors, but injecting that solution into patients' running dialysis machines.

Saenz initially said that she was just cleaning the lines, but she was first fired and then arrested. CNN says that she was ultimately found guilty of killing five patients, and that the jury didn't believe the defense that claimed she was just being blamed for deaths that weren't her fault at all. The murder charges — along with other counts of aggravated assault — resulted in a life sentence with no chance of getting out on parole.

Stephan Letter

When Stephan Letter went on trial in connection with the deaths of 29 of his patients, he explained (via The Telegraph) that he'd thought he was doing the right thing. He stated: "I wanted to help the victims, out of spontaneous sympathy, although I now know how catastrophically wrong my actions were." The prosecution, however, wasn't buying it, noting that just before they died, some were on the mend and looking forward to being released from the Bavarian hospital where Letter was working.

His last victim died in 2004, and most shocking of all is that when he was arrested, it was for offenses that included the theft of a fax machine and some missing drugs. It wasn't until Letter confessed that hospital authorities had any idea there was murder going on, says The Guardian.

Letter received a life sentence for his conviction on 12 counts of murder and 15 counts of manslaughter, says The Irish Times, but it remains unclear just how many he killed. There were 83 deaths at the facility while he was working there, and Letter had confessed that even he wasn't sure how many he had actually killed. The investigation saw the exhumation of 42 of those people, and while some examinations seemed to show signs of foul play, Letter's precise body count remains unknown.

Kristen Gilbert

Kristen Gilbert, says The Boston Globe, wasn't just a nurse at the Northampton Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, she was one of the most popular nurses. But it was only after her arrest that authorities realized that she had been present for around half of the 350 deaths that had occurred at the hospital in her seven years of working there. Unlikely to be a coincidence? They thought so, too, especially in the case of Kenneth Cutting. Cutting was one of her patients in February of 1996, and according to the Associated Press, all kinds of alarm bells went off when she asked her bosses to leave work early if he were to die. And then — he died. And yes, she left early.

That was about the time that officials started looking into what they were realizing was a high number of suspicious deaths, and although Gilbert left her position at about the same time, fellow nurse Kathy Rix had already figured out — and would later testify, says The New York Times — that Gilbert had been using epinephrine to kill.

Gilbert went to trial, and according to CBS News, she narrowly avoided the death penalty in conjunction with her convictions for three counts of first-degree murder, one count of second-degree murder, and two counts of attempted murder. Instead, she was given a life sentence.