Aliens Might Look A Lot Like Humans. Here's Why

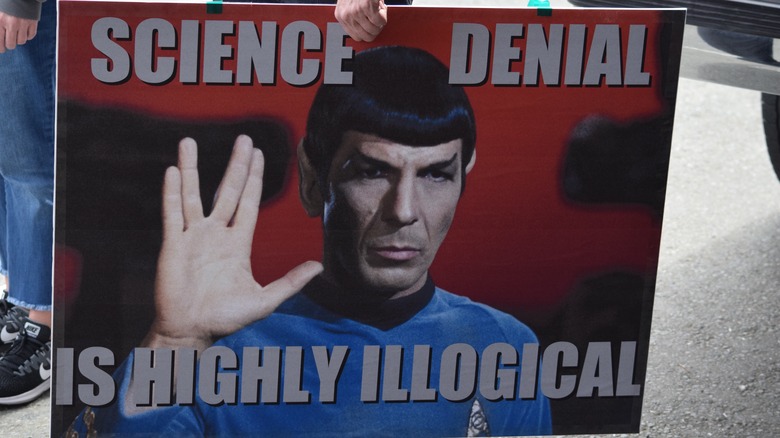

Sometimes "Star Trek" fans find themselves in the position where they have to defend all of the series' various rubber-headed aliens. Science-savvy folks naturally think, "There's got to be a huge variety of life in the cosmos. It's hubris and nonsense to think that alien intelligence would be bipedal humanoids. How would we even know life if we found it?" Fair point. Even the good folks over at PBS Spacetime did an episode about the possibility of life composed of one-dimensional cosmic superstrings living in the cores of stars. As the phrase goes, the absence of evidence is not the evidence of absence.

But at present, it really is the case — and this could be incredibly disheartening depending on where you stand — that life on Earth comprises the most complex forms of matter and energy that we know exist in the universe. Multicellular organisms, protein sequences, DNA and RNA, the neurochemical transmission of information — the best the universe has to offer. On the upside, the entirety of the observable universe and its 1 billion trillion stars is about 15 million times smaller in volume than the entire 23-trillion-light-year-in-diameter universe, per Forbes. Lots of room for improvement.

In all that vastness, though, aliens might look a like rubber-headed "Star Trek" species, after all.

Similar conditions, different places, same results

So think about this scenario: Two people from wildly different backgrounds — one from Ghana, the other New Zealand, one short, one tall, etc. — in their mid-30s wind up painting a single red tree against a green-tinted, rocky background. They meet each other, see each other's paintings, and say, "Oh my gosh, what are the odds?" and marvel at the unlikelihood of it all. And then they realize, "Oh. We're both using the same online store, admire the same artists, and have painted about 500 trees before."

That's a sociological version of what biologists call "convergent evolution" — when similar conditions at different locations produce the same result. This is why bald eagles can fly, and those really cute mouse-like sugar gliders (pictured above) can glide a bit. Bald eagles hail from Canada down to Mexico (per the National Wildlife Federation); sugar gliders hail from Australia, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea (per National Geographic). Never have the two met, and they evolved on totally opposite sides of the globe. We have to go back some 300 million years to find their common ancestor, amniotes, in a time when the Earth was a single continent, Pangea (per Field Museum).

But Canada and Indonesia both have trees, which produce height differences between objects along terrain. Both also have other flying creatures that can be caught for food. So, in the end, similar conditions yielded similar traits — winged appendages. "Feathers versus skin flaps" exemplifies convergent evolution.

Sharks, flowers, and Vulcans

Expand this line of reasoning to life forming on different planets. Imagine that the special cocktail of an Earth-like atmosphere (nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, etc.), temperature and distance from a star, strength of gravity, and so on exerts its influence on life developing on a distant world. Assume that molecules invariably form more and more complex chains, which develop into microorganisms, then single-celled organisms that compete for resources. Life needs to absorb nutrients, replicate itself, etc. In the end, this planet has a multicellular organism like the cashier at your local Trader Joe's.

This is exactly what some scientists — such as Simon Conway Morris — think is the case. Morris told The Independent: "If you want a sophisticated plant, it will look awfully like a flower. If you want a fly, there's only a few ways you can do that. If you want to swim like a shark, there's only a few ways you can do that. If you want to invent warm-bloodedness, like birds and mammals, there's only a few ways to do that."

Morris and others who agree — like those at Cambridge University behind the paper "Darwin's aliens" — say that if life becomes intelligent, it would necessarily want to exert control over its environment. For a being to exert control over its environment, it needs tools. Technological development would invariably move faster than biological evolution. And as such life strives to survive, it would organize itself based on rules. In the end, we've got Klingons and Vulcans.

One type of life amongst many

Before we go envisioning a galactic space federation of aliens chatting in English while quaffing Saurian brandy rather than regular old Earth brandy, it's important to look at some limitations of convergent evolution applied to alien species.

As zoologist and author of 2021's "Zoologist's Guide to the Galaxy," Arik Kershenbaum says on Mind Matters, "The trouble is, we don't know what aliens have for genes. So this is something we can't say is quite as universal as some of the other constraints of biology on Earth. It may be that the way that alien life forms are related to each other is completely different, and so their sociality may be completely different as well." In other words, the key feature of biological life on Earth is the transmission of attributes from generation to generation via genes. Without that copy-paste mashup mechanism, how could life on a whole persist (if it's mortal)? Also, we have no way to know whether or not alien life would relate to itself in collaborative terms, with cognitions and emotions like ours.

In the end, it might be helpful to think not of a galaxy or galaxies teeming with variously foreheaded aliens but rather consider that our particular version of life — if it exists elsewhere — might not be too dissimilar. And we could still live in a universe of incorporeal intelligence, complex cosmic strings hanging out in the cores of stars, or anything else not yet discovered or disproven.