The Untold History Of Amelia Earhart

Most people know that Amelia Earhart was a legendary pilot who mysteriously disappeared during her most daring journey. But the aviatrix was much more than that. In every aspect of her life, she fought against the strict gender roles of 1920s society. The fact that her disappearance was never solved is only one of the fascinating facts behind this record breaking pioneer.

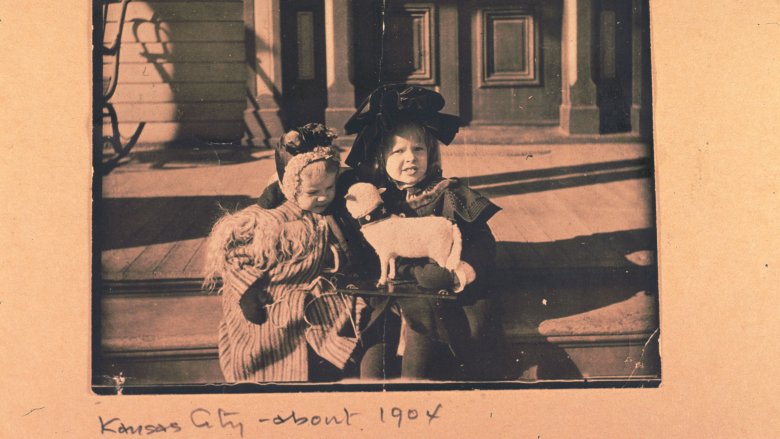

She came from a broken home

Earhart learned early on that a woman's life can't revolve around a man. That sounds like a pretty obvious piece of advice, but for a girl living at the turn of the century, it was revolutionary. Earhart was born in 1897 and lived a happy life as a tomboy in Atchison, Kansas until her dad, Edwin, picked up a new hobby — alcoholism. According to the book Amelia Earhart: Flying Solo, Earhart and her sister lived in constant fear of what their dad might do if he came home drunk. When Edwin decided that getting wasted was more important than supporting his family, Amelia's mother Amy moved the girls to Chicago to start over.

Now, this isn't a single-mother sob story. It was a daring move for Amy to leave her husband, but the family didn't end up destitute on the mean streets of Chicago. Amy had a healthy trust fund to keep the family afloat, according to Flying Solo. Still, a teenaged Earhart saw firsthand that a woman can be the breadwinner and life goes on whether you have a man or not.

She was a war nurse in World War I

Earhart was devoted to her studies in Chicago. Flying Solo explains that, before she enrolled, Earhart had to check out every high school herself to make sure that their chemistry and physics programs were up to snuff. Earhart planned on continuing her education after high school — until she saw the horrors of war.

In 1917, Earhart went to visit her sister in Toronto and came face to face with the many wounded soldiers from World War I. Suddenly, her esoteric studies seemed frivolous. "I'd like to stay here and help in the hospitals," Earhart wrote to her mother. "I can't bear the thought of going back to school and being so useless."

Though nursing was never on her radar, Earhart gave up everything to stay in Toronto for a year and help the wounded. It changed her life forever. While working as a nurse, Earhart would spend her few free hours at the airdrome, fascinated by the graceful, yet fragile planes in the sky. Earhart left Toronto knowing that life was short and shouldn't be wasted. So, she was going to fly.

She studied pre-med at Columbia

After her year of nursing, Earhart said in her memoir that she developed an infection behind her cheek that got bad enough to require surgery. She desperately needed rest, so it wasn't a great time to start a flying career. After so much time in hospitals as a nurse and a patient, Earhart wanted to study medicine and perhaps become a physician.

In 1919, Earhart enrolled at Columbia University and began a pre-med program. She enjoyed her studies, but she soon began to wonder if she really wanted to be a doctor after all.

"Visions of [medicine's] applications floored me. For instance, I thought among other possibilities of sitting at the bedside of a hypochondriac and handing out innocuous sugar pellets...This picture made me feel inadequate and insincere," she wrote in her memoir. So, after a year, Earhart ditched her doctor dreams and moved out to California.

By 25, she bought her first plane

Once Earhart really committed to aviation, she didn't mess around. Earhart left Columbia in 1920 and got her flying license in 1921. Her flight instructor, Neta Snook, described Earhart as a natural flyer and a "serious student." According to the book Amelia Earhart: The Sky's No Limit, Earhart bought her first plane in 1922 for $2,000. The bright yellow Kinner Airster, nicknamed The Canary, wasn't the most reliable piece of equipment. Snook described it "like a leaf in the air." With a 60 horsepower engine, it's not shocking that The Canary wouldn't win any awards for speed and stability. For perspective, your average Ford Focus has 160 horsepower and one engine from a Boeing 777 puts out more than 110,000 HP.

Still, Earhart loved her little plane and flew as often as possible. On one flight with Snook, a clogged cylinder in the Canary forced Earhart to crash into a line of trees. Snook crawled out of the wreckage to find Earhart pleasantly powdering her nose. "We have to look nice when the reporters come," she said. It was the beginning of Earhart's role as the face of female aviation.

She broke records by crossing the Atlantic twice

Earhart got her big break when pilots Wilmer Stultz and Louis "Slim" Gordon planned a flight across the Atlantic and invited her along. She wouldn't get to fly the plane, but would be the first female passenger to cross the sea. Quite a feat for the time.

If sitting on a plane doesn't sound like much, remember that flying in 1928 was a lot harder than boarding a Southwest flight. In Earhart's book, Last Flight, she described a harrowing scene. In flight, a cabin door broke and Earhart recalled, "Slim came within inches of falling out when the door suddenly slid open. And when I dived for that gasoline can, edging towards the opening door, I too had a narrow escape. However a string tied through the leather thong in the door itself and fastened to a brace... held it shut." The flight made it and Earhart became a national celebrity.

Still, Earhart wasn't content to win praise for just being a passenger. In 1932, she piloted her own plane across the Atlantic, the first woman to try the daring flight. At one point she went into a vertical spin of 3000 feet, according to Last Flight. "How long we spun I do not know...As we righted and held level again, through the blackness below I could see the white-caps too close for comfort." Earhart made it out alive and cemented her place in aviation history.

She had the first celebrity fashion line and wrote for Cosmopolitan

Earhart became America's beloved aviatrix. She was a huge celebrity, so she decided to leverage that power to make money for her upcoming flights. Known for her boyish flight wear, Earhart started a clothing line to give her style to the masses and build funds for her future adventures. Way before the Kardashians, Earhart pioneered the idea of a celebrity fashion designer. Her clothes were basically sportswear, though Earhart told journalists that she'd always add "something characteristic of aviation, a parachute cord or tie or belt, a ball-bearing belt buckle, wing bolts and nuts for buttons." The clothing line was meant to give women across the country the freedom to move and find adventure.

Cosmopolitan Magazine jumped on the new flying frenzy. At the time, Cosmopolitan offered female advice that went beyond "Things to do in bed that'll drive him wild!" and they made Earhart their "Aviation Editor." Yes, they wanted enough material about aviation that they needed a full-time editor on staff. Earhart used her articles to answer questions about flying and to encourage girls to pursue aviation. Earhart cherished her opportunity to speak to a wide range of women about the field she loved so dearly.

She had a secret wedding

Though Earhart was a self-driven woman determined to be a pioneer in flight, she had some help along the way from George Putnam. Putnam was a successful publisher and married man who managed Earhart's career after her first transatlantic flight. The two worked together on her books and public appearances and the friendship quickly developed into an affair. Putnam and his wife divorced, but Earhart didn't want to rush into marriage, according to an article in Connecticut Magazine.

Earhart wrote to a friend, "I am still unsold on marriage . . . I may not ever be able to see [it] except as a cage until I am unfit to work or fly or be active." That didn't stop Putnam from proposing. After his sixth attempt, Earhart gave him a letter detailing everything she needed in order to marry him, as explained by Slate. "I want you to understand I shall not hold you to any midaevil [sic] code of faithfulness to me nor shall I consider myself bound to you similarly."

She continued, "Please let us not interfere with the others' work or play." And "I must exact a cruel promise and that is you will let me go in a year if we find no happiness together." Putnam agreed to the terms and according to Connecticut Magazine, they married in a tiny, secret ceremony in 1931. Though she eventually revealed her secret wedding, Earhart never took his last name or sacrificed her independence for marriage.

Before her final trip, she declined a chance to learn a new navigation technique

On Earhart's final flight, she and navigator Fred Noonan got lost somewhere over the Pacific Ocean and disappeared, never to be seen again. Leading up to the fatal flight, Earhart was given a chance to learn new techniques of navigation, but turned it down.

Navy Lt. Commander Phillip Van Horn Weems was an innovator in celestial navigation and taught his techniques to many pilots, including Charles Lindbergh. With his technique, a pilot would use a sextant and the sun or stars to get an accurate read of their position. That was worlds better than the nearly blind flying Lindbergh and others had to do.

After Earhart's first transglobal flight attempt crashed on takeoff and was a complete disaster, Weems reached out to offer his navigational knowledge. In a letter to the pilot, Weems pleaded for Earhart to study celestial navigation with him before making another around the world attempt. But Earhart wanted to get back in the air as soon as possible. So, Putnam declined on her behalf and Earhart began her last flight in June of 1937.

There are lots of conspiracy theories around the disappearance

The nation was utterly shocked by Earhart's disappearance. It seemed impossible. Most people believed she got lost, ran out of gas, and crashed into the ocean, but that theory was never confirmed. Without a concrete story for her disappearance, conspiracy theories ran rampant.

For instance, some people believe that Earhart wasn't just a pilot — she was a spy! Hired by FDR! To spy on the Japanese! Their theory is that Earhart crashed, the Japanese found out she was a spy, and killed her. The fact that Earhart never got anywhere near Japan didn't seem to bother theorists. The 1943 Rosalind Russell movie about Earhart, Flight For Freedom, promoted the conspiracy further.

Meanwhile, in the 1970 book Earhart Lives, the authors claim that Earhart's disappearance was just a ruse. According to the book, Earhart wanted out of the spotlight, so she faked her death and lived out her life in New Jersey as Irene Bolam. The big problem with that theory of course was the real Irene Bolam, who denied being Earhart and sued the book's publishers for $1.5 million. The suit was eventually withdrawn, and Bolam died in 1982.

The theories don't end there, however. Rumors also swirled about the Bermuda Triangle being to blame for her disappearance, but she never flew anywhere near the vile vortex. Of course, there's always aliens. Some think either by accident or through her work with the government, Earhart was whisked away to another planet. They did make a Star Trek Voyager episode out of that story, so it's at least the most entertaining of the theories.

Did she survive as a hostage in Japan?

Probably not, but let's take it from the top. As reported by NPR, producers of History's new documentary Amelia Earhart: The Lost Evidence said they uncovered an old photo of Amelia Earhart in the Japanese-controlled Marshall Islands. It shows people on a dock, including what appears to be a short-haired woman. Despite either crouching or sitting with her back to the camera, the producers argued this was Earhart. (And the man on the far left was supposedly her navigator, Fred Noonan.) They believe the Japanese found her on Mili Atoll Island and held her hostage on the Marshall Islands. What's more, according to the documentary, the U.S. might've known Earhart was a prisoner and still done nothing.

From the start, this theory was widely criticized. Richard Gillespie, head of the International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery, thinks it's just random people on a dock. According to an early interview with The Guardian, he believed the woman's hair was too long to be Earhart's. Besides, his team has done multiple excavations of Kiribati Island, and he believes she crashed and died there. Meanwhile, the Japanese claim no records of Earhart as a prisoner.

But the big nail in the coffin came a couple weeks later. According to The Guardian, a Japanese military history blogger needed only 30 minutes to find the photo in a travel book that was published almost two years before Earhart's flight. Sorry, folks.

The mystery is likely solved

The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) have been diligently researching the Earhart crash for years and the believe the Earhart mystery is solved. According to their theory, she never actually crashed. Instead, she died a castaway on a deserted island.

In 1940, three years after she disappeared, British authorities found a partial skeleton on Nikumaroro, a tiny island near Earhart's intended landing place. At the time, they ruled that the bones were male. But according to The Telegraph, TIGHAR consulted with a forensic imaging specialist, Jeff Glickman. By comparing the records of the bones' measurements and photographs of Earhart, Glickman found that the bones were very likely a match for the missing pilot.

Speaking with CNN, TIGHAR's executive director Ric Gillespie explained, "There are historical documents that prove official airlines received radio calls for help in 1937. If we look at the press of the time — people believed she was still alive. It was only when planes were sent to fly over the islands where the distress signals were coming from and no plane was seen that the searches shifted towards the ocean."

So where'd the plane go? According to TIGHAR's explanation, the plane was washed into the ocean from the reef with the tide. Moreover, rescuers did find "signs of habitation" on Nikumaroro. They assumed it was from natives of the island — but in truth, it had been uninhabited since 1892. TIGHAR later excavated the site and found evidence of campfires, parts of a woman's shoe, and a box that once held a sextant. All matches for what Earhart had on the plane.

Though we'll never know for sure, evidence seems to suggest that TIGHAR's castaway theory is true. Earhart wasn't a woman lost at sea, but a pioneer who struggled to stay alive in the darkest of circumstances.