What An Asteroid Strike Would Really Do To Earth

Let's make one thing clear: the chances of an asteroid hitting Earth are very, very small. Yes, it's happened before, and things were pretty rough afterward. But keep in mind that the last major asteroid impact happened about 66 million years ago, and the dinosaurs around at the time didn't have the sort of monitoring equipment we do now. So, while it's worth considering what might happen, please don't consider this an opportunity to get out your "The End is Nigh" sign and take up a spot on your local street corner.

But as much as asteroid strikes of smaller size are fascinating and can have serious impacts in the immediate vicinity of the hit, they don't have the same Hollywood blockbuster-style effects as a really big one. So, we're going to mainly concentrate on the worst-case scenario in order to understand what a mountain-sized hunk of space rock can really do when it slams right into our planet.

We've got a pretty decent model for that. About 66 million years ago, an asteroid more than 10 miles wide slammed into the Yucatan peninsula, leaving behind a 12-mile deep, 93-mile-wide scar now known as the Chicxulub crater (via The Harvard Gazette). It's not the largest known crater on our planet — that would be South Africa's Vredefort Crater, which NASA reports was created some 2 billion years ago. Yet, Chicxulub's more recent impact gives us greater information on just what a humongous asteroid could really do to Earth.

The effect depends on the size and impact location

According to Scientific American, Earth is struck by relatively small bits of rocky matter, like meteors, all the time. Meteors, for what it's worth, are effectively small bits of an asteroid that have chipped off a parent rock. We can deal with most of those just fine. Meanwhile, it's easier to spot the really large asteroids that may be hurtling towards our planet, thanks to more advanced monitoring techniques. The ones in the middle, sometimes dubbed "city killers," are more concerning, namely because they're harder to spot in the vastness of space and yet can still cause serious damage. Even the relatively small 60-foot meteor that disintegrated over the Russian city of Chelyabinsk in 2013 caused some injuries from a shockwave that generated broken glass, as the New York Times reported.

Even if an asteroid is relatively large, where it strikes our planet really matters. The asteroid that caused the Chicxulub crater and effectively wiped out most of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago was made all the more destructive because it hit land, says the Natural History Museum. If it had struck further to the east, it would have impacted in deeper water and therefore thrown up less debris. With less debris floating around in the atmosphere to rain fire down below and block out sunlight, the resulting impact winter — where the particulate matter in the atmosphere blocks out sunlight and lowers global temperatures — may not have been so bad.

If an asteroid were big enough, it's the wind that could do you in

Now, of course, if you happened to be standing in the center of what would be the Chicxulub crater 66 million years ago, it's all but certain that the intense heat and pressure generated by the plummeting asteroid would have spelled your doom. At least it would have been fast. But, if you were to move outside of the immediate zone of doom, what would be the agent of your destruction instead? Would it be a firestorm? A pressure wave? A really big chunk of rock flying in your direction?

Ultimately, it could have been any of those things, but it's more likely that you would get done in by the wind. Of course, this isn't just any sort of wind, and it's definitely not some gentle breeze blowing through the park on a balmy spring day. According to Vox, the wind generated by a Chicxulub-size impactor would be enough to smash buildings to the ground in an instant. Plus, the shockwave that would accompany such a wind would do nasty things to your internal organs, making it all but impossible to survive such a blast. Ultimately, this intense wind would end up being the number-one killer in the event of a large asteroid impact, at least in the immediate aftermath of a strike.

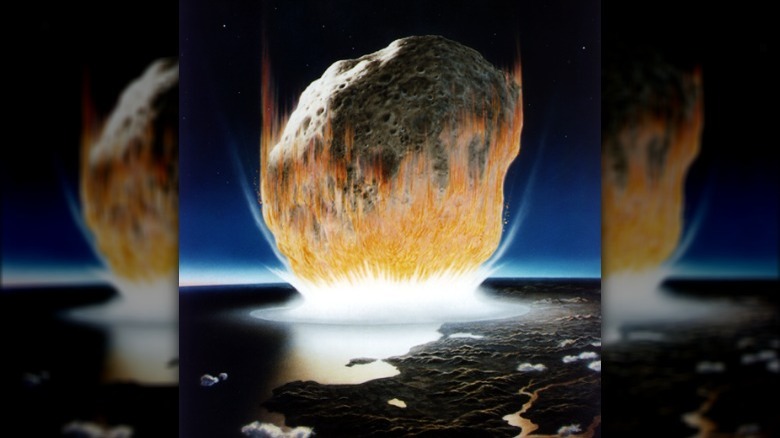

The atmosphere would be superheated

For most of our lives, we probably don't think about the air around us. We absolutely need to breathe it in to survive, of course, but it's generally colorless, easily accessible, and offers little to no resistance when we're moving around. That might change a bit on a particularly windy day, but the fact remains that we don't really consider the physical nature of our atmosphere. But if a gigantic rock were starting its descent into that atmosphere, we'd become aware of the unique nature of air very quickly. That's because, with a sufficiently large asteroid, the atmosphere around it resists the incoming force, compresses, and becomes incredibly hot, as WIRED notes.

How hot? Bodies of water in and immediately around the impact zone would be vaporized in a near-instant, for one. The relatively shallow water that covered at least part of the impact zone pre-Chicxulub would have been blasted away to nothing. Rock in the area would move in a wave like water, too. It simply has to, given the very fast transfer of kinetic energy from the asteroid to the surface of the planet. And that energy moves so quickly that the rock effectively melts. As per WIRED, it's briefly enough to make things hotter than the surface of the sun, so much so that the resulting shockwave isn't just full of deadly wind or melting rock, but also ionized plasma to add an extra cherry on top of that disaster sundae.

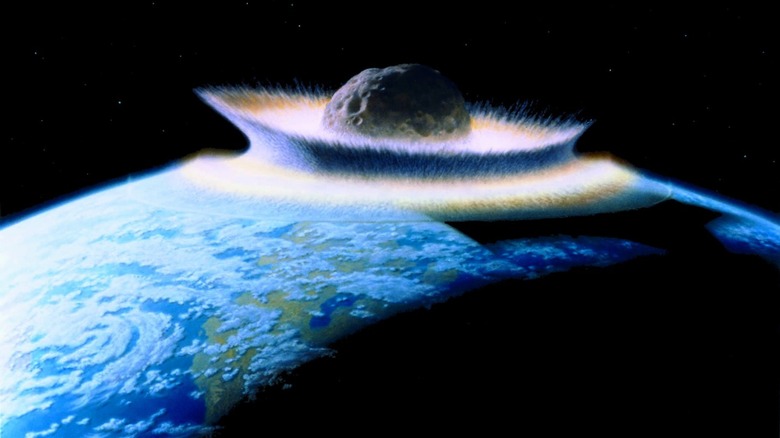

Everything would move very, very fast

It's estimated that the Chicxulub impactor went through the atmosphere in about three seconds, plummeting through 60 miles of gasses and clouds before slamming into the earth (via WIRED). Or, in other words, a smaller mile-wide meteor (the Chicxulub impactor is estimated to have been three times as large) would travel through the atmosphere and hit the surface at a speed of about 30,000 miles per hour, according to How Stuff Works. All of this is to say that many of the first-wave effects of the asteroid strike, like crater formation, superheated atmospheres, and shockwaves, would happen in very quick succession.

Even if you were as far as possible from the asteroid strike site, you would know about it in short order. Dinosaurs and other creatures on the opposite side of the planet from Chicxulub would probably have felt the ripples of the asteroid's impact within a mere half-hour, according to WIRED. That's because the wave of pressure generated by the event would be traveling somewhere in the neighborhood of 1,000 miles per hour. Need more numbers? The rock of the crust would move in a wave outward from the epicenter of the strike at a rate of about 2.5 miles per second, generating such violent acts in such a short amount of time that earthquakes and tsunamis would result in short order.

A big asteroid would create big tsunamis

Let's say you survived the shockwave. You also managed to escape any immediately awful injuries from earthquakes or falling debris. Perhaps, at this point, you think that you might just have a chance of making it. And you might — so long as you're not in your beachside condo.

That's because a really large asteroid will also generate considerable tsunamis worldwide. Just how big? Going back to the Chicxulub impactor, scientists estimate that it would have created waves that were up to a staggering 1,500 meters high, or nearly 5,000 feet (via Eos). What's more, that would have been just the first set of these things. As water flooded back into the massive crater, it would have triggered yet more waves that then spread out across the planet. Even if you were as far away as the Pacific Ocean at that time, you could have seen towering walls of water up to 45 feet tall. Given that we don't know exact details about what shorelines would have looked like 66 million years ago, we can't be sure of the specific effects of these tsunami waves. Regardless, they were likely devastating.

For a more modern point of view, the International Tsunami Center notes that a roughly 3-mile-wide asteroid hitting in the midst of the Atlantic Ocean would produce waves that would wash over the Eastern seaboard and all the way to the Appalachian Mountains. Coastal cities from New York to Miami would be obliterated.

Flaming debris will be a major issue

If you've managed to get out of the way of the asteroid's pressure wave and the immediate splash of liquified or rocky debris, you're still not in the clear. In fact, you should take cover as quickly as you can.

According to WIRED, an asteroid like the Chicxulub impactor would have thrown up some 25 trillion tons of our planet's crust. All of that rock and dirt gets thrown around, with some reaching just the right trajectory and speed to escape Earth's gravity. But a lot of that debris will get tossed up into the atmosphere for a little while before zooming back to the surface. During the course of that trip from the upper atmosphere to the ground again, the debris superheats and becomes glasslike, turning into what's known as tektites.

Okay, glass hail is bad enough. But the collective movement of all these bits, regardless of how big or small they may be, will be enough to generate some serious friction and heat. In this case, the atmosphere turns into a superheated oven in some places, setting the lands beneath it on fire. Even places thousands of miles from the crater will have to deal with this deadly aftereffect. The best solution? Hide. Back in the Cretaceous, it appears that burrowing animals and those that could lurk in water fared best. For humans, a properly deep cave or doomsday bunker may be our best bet.

You would also need to consider wildfires

It should perhaps come as no surprise that, with the intense heat generated by a large asteroid strike, not to mention all of the flaming debris plummeting from the skies, that wildfires would be an issue after an impact event. This is one event that, even if you're on a part of the planet that's far removed from the immediate crater, will be pretty hard to escape.

According to the Lunar and Planetary Institute, a large asteroid impact would lead to wildfires across the planet, both from heated debris and superheating of the atmosphere. We know that it happened after the Chicxulub crater was formed, given the amounts of soot and ash in the geological record, found as far afield as Denmark and New Zealand. What's more, paleobotanists uncovered evidence that, right after the impact, ferns were shedding spores like crazy. After modern wildfires and similar events, ferns and other angiosperms grow quickly and produce a high volume of spores, too. While ferns may have been happy, few other plants and animals would have done well. Wildfires certainly devastated habitats and removed vital food resources for herbivores and carnivores alike.

Smoke would, naturally enough, be another major issue. Ash would pollute the atmosphere, as well as a variety of gases that didn't exactly help things grow and recover in the aftermath, like carbon dioxide, methane, and an estimated one trillion metric tons of carbon monoxide that swamped the planet after the Chicxulub impact.

Watch out for the deep freeze

So, an asteroid of massive proportions has hit the Earth. You've avoided the impact zone, flaming hail, deadly winds, and massive tsunami waves currently lapping at the Appalachian Mountains. Even the widespread wildfires have passed on by. Lucky you! Well, kind of, since we're not done yet — not by a long stretch. Now, we've got to deal with a serious winter.

According to a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the impact winter after the Chicxulub crater was formed occurred thanks to particulate matter in the atmosphere. Dust was thrown into the upper reaches of our atmosphere, where it blocked significant amounts of sunlight from reaching the surface below. How significant? The study found that sea temperatures plummeted by as much as 12.6 degrees Fahrenheit. What's more, the atmospheric and temperature disturbances appear to have kicked off massive hurricanes.

For many creatures around at the time, this was the final death knell. A paper from Geophysical Research Letters reports that more than 75% of our planet's species went extinct around the time of the impact, though the authors admit that picking out just what killed each animal is difficult 66 million years later. That said, any creatures living at high latitudes (closer to the poles) had a better chance of survival, or at least experienced less environmental disruption. Perhaps, in a modern impact scenario, some sort of polar bunker with good heating would serve you well.

There are some places you might survive long-term, but it's tricky

At this point, it may seem like surviving an asteroid impact is all but impossible. Yet, we know that the various asteroid strikes throughout our planet's history did not wipe out all life on the face of the Earth, despite the towering waves, killer firestorms, and devastating impact winter that followed events like the Chicxulub impact. So, take heart. There's clearly a way to make it through, even if you don't have the benefit of a bunker or a seat on some billionaire's rocket to the Moon.

Ultimately, however, long-term survival is based on luck. For the Cretaceous extinction kicked off by the Chicxulub asteroid, creatures that lived on tropical islands on the other side of the world from the crater had the best chances. According to WIRED, they would have escaped the worst of the climate changes after an impact (maybe we should rethink that polar bunker, after all).

What's more, they would have had the greatest supply of available freshwater. That's because, in the event of a massive chill, much of the available water would stop evaporating. With water locked up in ice, rainfall could drop by as much as 80%. Outside of these islands, unfortunate Cretaceous critters not only had to deal with increased cold and decreased food sources, but they were likely to have to do it all in a nearly rain and snow-free desert.

Other animals might survive an asteroid impact

We must face the unfortunate fact that we are rather clunky creatures. We're smart, sure, and we've got these neat opposable thumbs. But, because of those big brains and relatively large bodies, we're also energy hogs (though, as Duke University notes, we're not as bad as some other animals). If some of us managed to survive the immediate effects of an asteroid strike, the resulting impact winter would make growing, gathering, and harvesting food potentially very difficult.

Then again, maybe it would be best to be a different animal entirely. According to WTTW, animals with diverse diets appear to have done better during the Cretaceous extinction than their more single-minded counterparts. Specialist herbivores probably fared the worst of all, given that their food sources were likely devastated by the effects of the asteroid strike. Small mammals may have also made it because they required fewer calories and were able to wait out the worst aftereffects in burrows. These almost certainly included our own distant ancestors, the squirrel-like plesiadapiforms, who emerged from their likely burrows to proliferate in a dinosaur-free world (via Inverse).

Humans might figure things out, though. We (or at least our hominid ancestors) have in the past, when smaller though still pretty sizeable asteroids have hit the planet, says Big Think. Living deep underground in geothermally-heated bunkers could work, or perhaps sturdy habitats on the surface could help mitigate the effects of an impact winter.

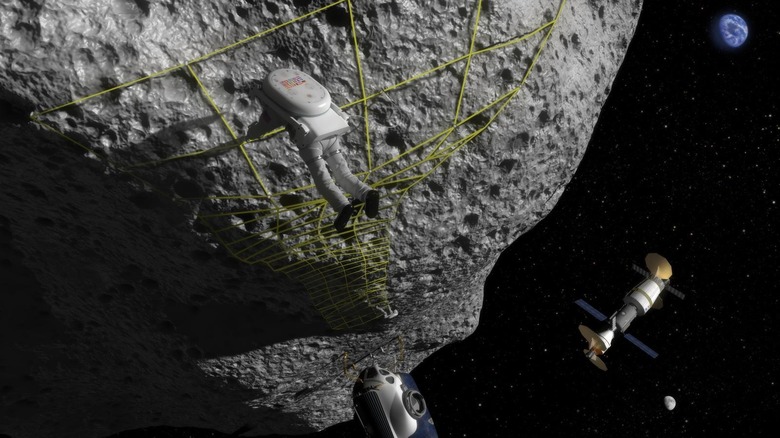

A big asteroid could mobilize a serious human effort in space

Though medium-sized asteroids could theoretically catch us by surprise, the massive sort of space rock that contributed to the Cretaceous extinction would be more likely to catch our attention. That's because we're watching the skies with programs like NASA's automated Sentry system (via Jet Propulsion Laboratory).

If a program or human observer spots a really big one hurtling towards Earth, we might already know how to deal with the threat. In 2021, NASA launched its Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) as a dry run for just such a situation. According to NBC News, DART will impact a small and generally non-threatening asteroid, Dimporhos, in fall 2022. By crashing DART into the smaller body, scientists will be able to study how we could change the rock's course. Dimporhos also orbits a larger asteroid, Didymos, giving scientists even more information to work with in the aftermath.

That said, getting our act together to deflect an extinction-level sort of asteroid would take a lot of effort. DART alone cost $325 million, for instance. And Forbes notes that it's not all on NASA. There are quite a few different space agencies, from Russia to China, that would need to play nice with each other for a mission to really work. And while some people left behind on Earth would be building bunkers, others might take to the Moon or even Mars to establish colonies should the worst happen to our own planet.