The Mystery Of The Lost Colony Of Roanoke

American history is full of unsolved mysteries, from Amelia Earhart to D.B. Cooper, but none are quite so eerie as the lost colony of Roanoke. In 1587, over 100 English colonists landed on an island off the coast of modern-day North Carolina. Three years later, they'd all vanished. The fate of the colony still puzzles historians to this day. And while there are plenty of fascinating theories about what might've happened, researchers are still trying to solve the mystery of the lost colony of Roanoke.

The first two expeditions

The mystery of Roanoke all started with Queen Elizabeth I and her favorite explorer, Sir Walter Raleigh. Elizabeth wanted to establish a base in the New World where colonists could search for gold, preach to the locals, and keep an eye on their Spanish rivals. So in 1584, Raleigh sent an exploratory mission to the Carolina coast, and according to most accounts, the English explorers got along relatively well with the people living on Roanoke Island. In fact, they even took two natives back to England when they finally returned home, as per Boston University.

The second trip in 1585 was not so successful. Hoping to establish a more permanent colony, Raleigh sent an all-male group of soldiers and laborers to Roanoke. But unfortunately, these newcomers thought the best way of making friends with their neighbors involved attacking villages, taking hostages, and beheading one of their chiefs, according to Encyclopedia Virginia. Naturally, this didn't sit well with the natives who decided to get revenge. When you couple that with a severe food shortage, you can see why the English decided to give up on the colony and sail back home.

If they'd only waited a little while longer, they would've received a boatload of new supplies. But when reinforcements arrived, they found Roanoke deserted. Not wanting to give up their foothold in the New World, 15 soldiers were left behind to watch the colony, and Sir Walter Raleigh got busy gathering a third expedition, one that would sail across the Atlantic — and never return.

The third expedition

After the first two expeditions, Sir Walter Raleigh decided to send one more group in 1587. Only this time, the colony would be comprised of men, women, and children — a total of 117 souls striking out for the New World. The expedition would be led by Gov. John White, an artist involved in at least one previous expedition, as per Encyclopedia Virginia. However, the colonists weren't originally going to say on Roanoke. The plan was to drop by, pick up the 15 soldiers left behind, and sail on. But after landing, master pilot Simon Fernandez refused to go any further, forcing the colonists to set up shop on the North Carolina island.

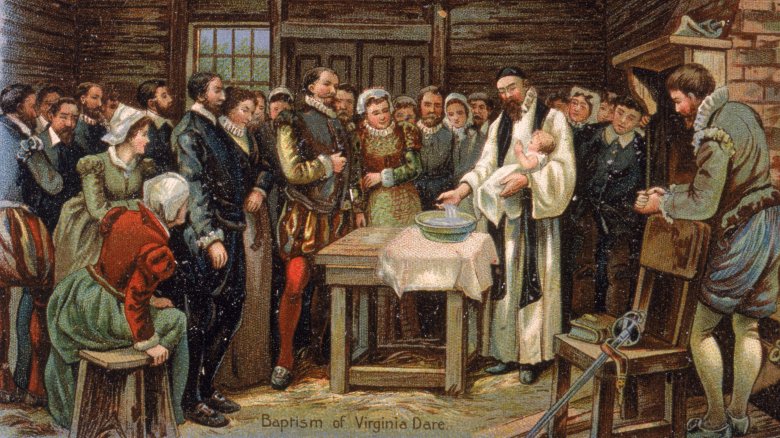

Upon arriving on Roanoke, the settlers found the bones of one of the 15 soldiers and not much else. This wasn't a great start for the new colony, but White was able to patch things up with the Croatoans, a tribe living on the nearby island of, well, Croatoan (today known as Hatteras Island). Unfortunately, things weren't completely cheery, as one colonist was killed by a different band of natives. Making things worse, the Roanoke settlers needed more supplies, so White was chosen to sail back to England and get help from Raleigh. White wasn't particularly thrilled about leaving, especially since his daughter had given birth to his granddaughter, Virginia Dare, just days before. Virginia was the first English child born in America, but as August 1587 came to an end, White left his family behind and sailed for Europe.

The disappearance of 1587

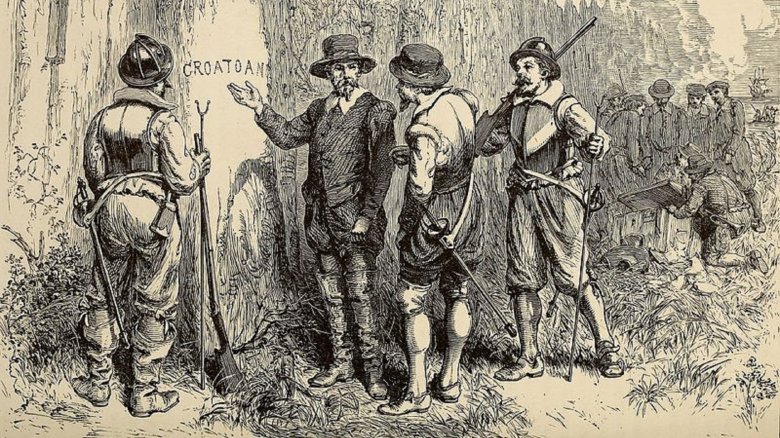

Unfortunately, thanks to England's war with Spain, it was three years before Gov. John White could return from the British Isles. And when he showed back up on Roanoke, he found the colony abandoned. He immediately began looking for Maltese crosses, signs the colonists were supposed to leave if they were in trouble, but he only discovered the letters "CRO" etched into a tree and the word "CROATOAN" carved into a post (via the North Carolina History Project).

White also noticed there was a new fort, and that the colonists had dismantled all their homes, as per How Stuff Works. It looked as if they'd packed up camp and moved out, but sadly, White wasn't able to launch a rescue party. Bad weather, impatient sailors, and a damaged ship kept him from searching for the missing settlers, and White was forced to return to England, leaving his friends and family behind to whatever mysterious fate had befallen them.

So what caused one of the most famous disappearances in American history?

The drought theory

Well, if you asked College of William and Mary archaeologist Dennis Blanton, he'd probably aim the blame for the colony's disappearance at Mother Nature. In 1998, Blanton co-authored a study (published in Science) that claimed the "Lost Colony" was hit with one of the worst droughts in North American history. But how does Blanton know this? Well, you see, the truth is all in the trees.

As explained by The New York Times, Blanton and his fellow researchers examined cypress trees in Virginia and North Carolina. These trees live for hundreds of years, and scientists can get a pretty good idea of what the weather used be like by studying the rings inside. And after looking at their size and shape, Blanton realized the Roanoke settlers were living through the worst American drought in the past 800 years. In fact, things were at their water-sucking worst in 1587, right as the colonists were getting settled in their New World digs.

This would've made things incredibly difficult for the colonists, especially since they didn't have any crops. The English expedition kept alive by hunting for food and trading with nearby tribes, and a drought would've had a major impact on both the nearby wildlife and the locals' willingness to hand over their much-needed corn. So Blanton theorizes the colonists called it quits and headed off to find somewhere with a little more food. It seems like these poor Englishmen were suffering from a case of rotten luck. As historian and Roanoke expert Karen Ordahl Kupperman puts it, this "was the worst possible time to start a colony" (via Gizmodo).

The assimilation theory

One of the more popular theories about Roanoke says the colonists left their homes and assimilated with friendly native tribes, such as the Croatoans. This is supported by some anecdotal evidence, as Jamestown search parties heard interesting stories as they looked for the missing settlers. As pointed out by Brian Dunning of Skeptoid, one Englishman named William Strachey described hearing of an Indian village where there were "howses built with stone walles and one story above another, so taught them by those Englishe who escaped the slaughter at Roanoak." More convincing still, another described seeing a young boy dressed as a native, even though he possessed "a head of haire of a perfect yellow and a reasonable white skinne ..."

This theory seems to hold water, especially if there wasn't a lot of water on Roanoke at the time. As explained by archaeologist Luke Pecoraro, if there was really a mega-drought going on, joining forces with the locals would've kept the settlers from dying off. This would've also led to intermarriage, thus explaining accounts of natives with "gray eyes" or European-dress.

Going even further, Josh Clark of How Stuff Works posits the marriage between Roanoke settlers and native peoples gave birth to the Lumbee tribe. As Clark points out, the Lumbee were known for speaking English, and many members have last names like Hyatt and Taylor, similar to some of the colonists who disappeared. Plus, in their oral histories, the tribe actually claims to have descended from the Roanoke colonists. Not everyone buys this particular theory, but it's a lot more compelling — and a lot more pleasant — than some of the other theories out there.

The murder theory

As Brandon Fullam writes in "The Lost Colony of Roanoke," by 1609, the English government thought the colonists had fallen to some powerful enemy. Word had gotten round that Chief Powhatan (of Pocahontas fame) had killed off the settlers, and that he'd supposedly confessed his dirty deed to none other than John Smith, pictured above.

While the famed explorer never wrote about this in any of his books, he allegedly shared the story with an Englishman named Samuel Purchas, who printed the tale in his own book, "Hakluytus Posthumus." But there are some problems with this whole angle.

For starters, why would Powhatan confess to killing English colonists to an English explorer? That seems like a risky move. Plus, we only "know" about the Powhatan confession from a third-hand account, so it's possible Smith or Purchas made the whole thing up, that the Indian chief was lying, or that Purchas was misinformed. Overall, this theory's built on a lot of conjecture without much solid proof. And Powhatan isn't even the only suspect.

Some believe the Lost Colony was killed by the Spanish, who wanted revenge against England for that 1588 Spanish Armada debacle. On top of that, Roanoke was a key location for controlling the eastern coast. However, as pointed out by Shawn Miles of Ohio University, if the Spanish had really planned an invasion of the English island, there'd be some paperwork somewhere — an order, a ship log, a manifest — proving the government had actually okayed an attack. But as there's no documentation anywhere, it looks like the Spanish are in the clear.

The conspiracy theory

Anthropologist Lee Miller, author of "Roanoke: Solving the Mystery of the Lost Colony," has a different theory. She believes that a key player in Queen Elizabeth I's court conspired to make sure the colonists stayed lost for good.

According to Miller, Sir Francis Walsingham — Elizabeth's secretary of state and spymaster — plotted to betray the Roanoke colonists in order to discredit his political rival, Sir Walter Raleigh. After all, the two men didn't see eye-to-eye on how to deal with Spain, plus Raleigh had a patent to colonize the New World, which Walsingham allegedly wanted for himself. Moreover, the super spy supposedly wanted to control Roanoke for his own interests.

As part of his supposed scheme, Walsingham had John White's pilot, Simon Fernandez, drop the colonists off at Roanoke instead of taking them to Chesapeake Bay, their original destination. Walsingham allegedly believed the colonists couldn't survive on such a small island. Miller also argues that Walsingham tipped off the Spanish as to the settlers' location, hoping they'd wipe out the colonists.

Then, Miller says, when White went back to England for supplies, Walsingham prevented him from leaving for three years. As a result, the colonists were forced to move inland, where they were captured and enslaved by warring Indian tribes. Admittedly, this is all rather elaborate, and real-life conspiracies have a way of falling apart, or at least getting exposed, after a few centuries. Still, at the very least, Miller's theory would make for a pretty thrilling HBO series.

The Dare Stones

In 1937, a man named Louis Hammond made a fantastic discovery. While driving through North Carolina, he allegedly came across a piece of quartz covered in old-timey writing. Curious, he took the stone to Emory University and offered to sell the rock for $1,000. While most of the professors weren't interested, Haywood Pearce Jr. was incredibly keen to purchase the 21-pound chunk of quartz, as he believed it contained a message from Eleanor Dare, the daughter of Roanoke's governor, John White.

According to the text scratched into the stone, it appeared this rock was a tombstone for Dare's husband and her daughter, Virginia. It also contained a message explaining how the lost colonists were decimated by disease and Indian attacks, and at the bottom, there were the initials "EWD," which supposedly stood for Eleanor White Dare. Pearce and his father, the head of Brenau College in Gainesville, Georgia, eagerly bought the rock and soon offered $500 for a second stone that was mentioned in the carving.

As NCPedia details, that's when a guy named Bill Eberhardt showed up, claiming to have found 13 additional "Dare Stones." In fact, between 1939 and 1940, Eberhardt provided the Pearces with a whopping total of 42 rocks. And — surprise! — a couple of Eberhardt's friends also found some additional stones, bringing the total to 48. Sure, this all seems a bit fishy, but the Pearces were ecstatic, believing they could now trace the route of Elizabeth Dare as she traveled across the south. And the father-son duo weren't the only ones excited about the discovery, as it's said movie mogul Cecil B. DeMille considered making a film about this amazing discovery.

Unfortunately, everything fell apart when the Saturday Evening Post exposed the rocks as a hoax, explaining how Bill Eberhardt was a fraudster and how the writing and spelling on the stones didn't match other 16th-century texts. However, some say the first rock found by Louis Hammond might actually be the real deal. While it's never been verified, there are quite a few curious minds who wonder if the original Dare Stone might actually reveal the truth behind the Lost Colony.

The revelation of Site X

According to The New York Times, the North Carolina non-profit the First Colony Foundation (FCF) asked the British Museum to check out a map drawn by Gov. John White. Sure, this document (known as the Virginea Pars map) had been examined before, but never with modern tech a la x-ray spectroscopy. When the museum staff finished looking over the parchment, they made a pretty crazy discovery.

As it turns out, there's a patch on this map. Underneath, there's a little "X" about 60 miles west of Roanoke. That matches up almost perfectly with White's theory that the settlers had moved 50 miles into the mainland. So naturally, the FCF got busy digging at this so-called "Site X," and they found all sorts of artifacts, ranging from flintlocks to a jar for preserving food.

Most importantly, the archaeologists found fragments of ceramics called Surrey-Hampshire Border ware. According to Gizmodo, this stuff stopped showing up in America after the Virginia Company folded in 1624. So this discovery implies a lot of these artifacts come from the early 1600s or late 1500s, which coincides with the lost colonists leaving Roanoke.

However, archaeologist Nicholas Luccketti doesn't believe all the settlers moved to Site X. He theorizes maybe fewer than 12 were there briefly, while the others possibly moved to Croatoan, the nearby island home to their Indian allies. While there's still plenty to consider, Site X is one of the most exciting archaeological finds in the Roanoke saga.

But where's the actual settlement?

Just when you think you might have one mystery solved, another one pops up and takes its place. While archaeologists are getting closer to determining what happened to the lost colonists, they're not exactly sure what happened to the colony itself. While there have been multiple digs on Roanoke since the 1940s, nobody has actually found the 1587 settlement. Sure, they've found proof of the 1585 expedition, but when it comes to the fabled Croatoan crew, it's like all the evidence has just vanished from the Earth ... and possibly into the water.

According to a 2004 article in National Geographic, at least 600 feet of Roanoke has been swallowed by the sea. And if the colonists set up camp on the northern end of the island — as indicated by Gov. John White's records — then it's possible the lost colony is resting under the waves. For proof, researchers point to a 16th-century well and an old-timey ax head that were both found on the northern tip of the island, submerged underwater. It seems as if the land eroded away over time, plunging the colony into the Atlantic and keeping it hidden from would-be explorers. In other words, if archaeologists ever want to find this place, they might need to put on some scuba gear.