The Secret History Of The First Dollar Ever Made

Although the U.S. dollar is one of the most recognizable currencies in the world, it's likely that few are familiar with its humble beginnings. Americans today view the dollar as equivalent to green banknotes officially called Federal Reserve notes. But the first dollar was not made of paper or cotton as they are today (via CNN Money). In fact, according to the Mises Institute, the Founding Fathers abhorred the kind of paper currency used today, seeing it as a road to debt and slavery.

The "flowing hair" dollar of 1794, the first dollar ever minted, was the lynchpin of a new silver-based monetary system developed in response to the rampant inflation that had plagued the Thirteen Colonies before and during the Revolutionary War. This first dollar marked the birth of a rich yet turbulent tradition of American coinage. The system underwent numerous reforms and changes, and would end in favor of the current fiat monetary system in 1971 (via Investopedia). Here is the fascinating story of how the first U.S. dollar was born and how it, and its descendants, eventually died.

Before the Revolution

The story of the first dollar goes back well before the American Revolution. Money was a bit of a messy business in the Thirteen Colonies because there wasn't much of it to go around. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, early English settlers often bartered goods or used Native American wampum as money. English law banned the colonies from minting coinage, so settlers emitted bills of credit, which were promises to pay money in the future. But as with most paper currency, the non-standardized colonial bills were victims of rampant inflation from overprinting.

Massachusetts was the first state to mint its own coinage in defiance of the ban. These "pine tree" shillings were all stamped with a date of 1652 regardless of their actual date of creation. They never caught on much. Instead, colonists conducting trade with Spanish and Portuguese colonies in Latin America and the Caribbean introduced the milled Spanish dollar. According to the National Museum of American History, these dollars were machine-minted in Mexico and spread throughout the Americas through colonial commerce.

Colonial Williamsburg reports that the practice of milling created distinct grooved edges (similar to modern U.S. coinage) that made it easy to identify mutilated and counterfeit coins. But there were not enough Spanish dollars to pay for an expensive war, so when the American Revolution finally broke out in 1775, the Continental Congress had to find alternative ways to finance the conflict.

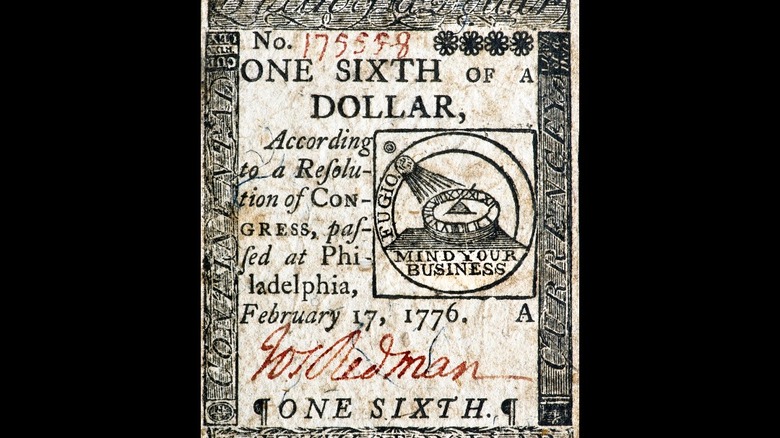

'Not worth a Continental'

In 1775, with the battles of Lexington and Concord, the "shot heard around the world" ignited the American Revolution. The next year, the Continental Congress issued the Declaration of Independence, heralding the birth of a new nation called the United States. Although the Revolution began in 1775, it took an eight-year war for the United States to achieve British recognition with the Treaty of Paris in 1783. The Revolution, like all wars, was expensive. According to the Mises Institute, the Continental Congress turned to the classic method of financing, printing bills of credit (aka paper money).

According to the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank, the Continental was not backed by precious metals. Instead, it was backed by the expectation that congress would recoup the bills in taxes from the states, take them out of circulation, and issue new currency. But the paper currency came with a myriad of problems.

First of all, few valued them due to their lack of real value. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts declared any opponent of the Continental "an enemy of the country" to force their acceptance. Second, they were easy to counterfeit. And third, the states never levied taxes on their citizens, who had no interest in paying them (remember "no taxation without representation!").

Thus, the Continental Congress issued new currency without withdrawing previous cash infusions. In 1780, Congress nearly went bankrupt (via Journal of the American Revolution). The Continental lost its remaining value. The resulting inflation forced local authorities to engage in price controls and other interventionist solutions to keep the war effort alive.

In the Founders' own words

In 1783, Great Britain recognized the United States. Now came the hard part: building a functioning country ("e pluribus unum") from 13 states whose interests often clashed. Among the major debates of the 1780s was the problem of money. According to the State Department, the United States was saddled with French and other debts. For the founders', it seems that currency printing was not a viable option.

George Washington, the first president of the United States, was at the forefront of opposition to paper currency printing. In a 1787 letter to Rhode Island governor Jabez Brown, Washington noted that paper money did nothing but "ruin commerce — oppress the honest, and open a door to every species of fraud and injustice." Washington did not elaborate, but it is likely that his experience with the worthless Continental to pay his soldiers influenced his view.

Thomas Jefferson's letters bluntly contextualize Washington's criticisms: "paper is poverty," he wrote. In a 1788 letter to Virginia statesman Edward Carrington, Jefferson noted that paper money is not money. It is not a safe, stable store of value, but "the ghost of money." As the Bank of England explains, notes are effectively an IOU that are redeemed for precious metals. An economy built on paper currency, according to Jefferson, collapses in hard times. Alexander Hamilton had warned of such a problem in 1783, since paper money depreciates as more is printed and eventually lands governments into unmanageable debt. To fix this problem, the United States needed hard currency. But disunity placed obstacles to this goal in the form of the Articles of Confederation.

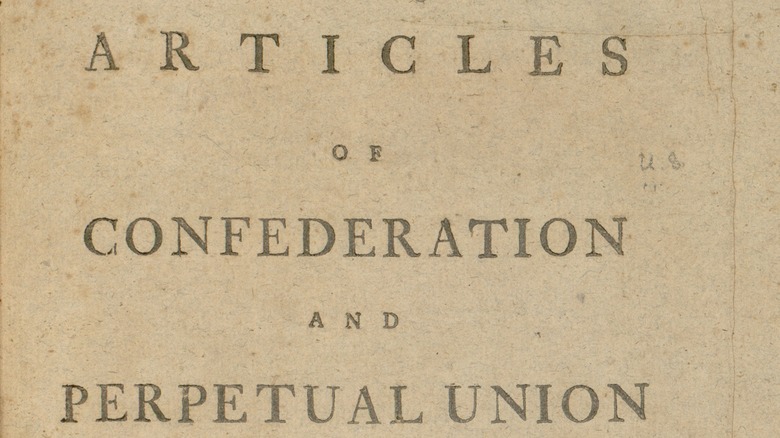

Commercial chaos under the Articles of Confederation

During its early years, the United States was hardly a unified nation. After the Revolution, the country was governed by a document called the Articles of Confederation (via Our Documents). According to the National Constitution Center, the Articles of Confederation created a loose union of 13 states that functioned de facto as independent countries. There was no executive branch, and the legislative branch had limited powers mostly related to common defense. It could not tax or levy troops without the consent of the states it represented.

Among the powers that congress did have was the power to coin money and set its value as put forward in Article IX. However, Article IX did not ban the individual states from issuing their own legal tender alongside that of the central government. So, Massachusetts, for instance, had its own dollar certificates from 1780. But not all states' currency was equally valued, making interstate commerce difficult at best. Furthermore, the United States was deeply indebted to France and other European countries that had financed the Revolution, so a national currency to create a functioning, unified economy and pay down national debts was desperately needed.

Congress gets the power to mint

To fix the mess that the Articles of Confederation had created, America's founders convened during the hot summer of 1787 in Philadelphia to draft a new document that would serve as the country's legal framework. The result was the Constitution of the United States. The document's strongpoint was the clear separation and enumeration of rights and duties to the states and the federal government. The federal government had the responsibility of national defense and guaranteeing basic constitutional rights, such as free speech, religion, and the right to bear arms. All rights and responsibilities not reserved to the federal government were delegated to the states or the people under the Tenth Amendment.

Among the rights that the states lost was the right to issue their own currency. Article I, section 8 of the U.S. Constitution (via Cornell Legal Information Institute) gave congress the right "to coin money [and] regulate the value thereof..." States, meanwhile, were forbidden under section 10 from emitting bills of credit (IOU's) or issuing their own money. Congress alone could issue money (but interestingly, not bills of credit), and by the words of the Constitution, as Forbes notes, it had to be gold and silver coinage, the only accepted state-level tender according to section 10. Such was the Founders' disdain for paper that according to the Mises Institute some wanted federally issued paper banned. Instead, they would establish a mint that would set the standards for American money whose value would be based on gold and silver, not government fiat.

The Coinage Act of 1792

On June 21st, 1788, the U.S. Constitution became the law of the land following New Hampshire's ratification and giving congress the two-thirds margin needed to enforce its provisions. But because there was no mint, the Spanish dollars, among other foreign coins, were still the favored medium of exchange in the United States. One of the hallmarks of a sovereign nation, however, is the issuance of its own coinage. Five years after the ratification of the Constitution, congress finally created the blueprint for the United States Mint.

The Coinage Act of 1792 was a monumental piece of legislation, although it is by and large forgotten today. Among the important provisions of the act was the creation of standard U.S. coins, some of which lasted into the 20th century. Section 9 listed that the mint would strike coins of gold, silver, and copper (unlike today's, which are made from base metal). Among these were eagles ($10), half eagles ($5) and quarter eagles ($2.50) alongside the more familiar dollars, half-dollars, quarter-dollars, dismes (today's dimes), half-dismes (nickels), and cents. Each coin had a set, legally required amount of gold, silver, or copper, which presumably helped guard against counterfeiting and prevent debasing of the currency. The integrity of the national currency was taken so seriously that debasing currency as an employee of the Mint was a capital felony. Imagine if this were still in force today.

What is a dollar?

The Coinage Act's archaic language and units make it difficult for modern audiences to grasp its importance. The number and units do not mean much to people today because the popular definition of a dollar has changed. If someone today were to define a dollar, they would undoubtedly pull out a $1 bill. These bills, however, are Federal Reserve Notes. Each is a bill of credit, which is a promise to pay money. It's an excellent example of Jefferson' "ghost of money." It is not what sound money proponents refer to as a "constitutional dollar" (via Mises Institute) since it is not made of precious metal.

Fortunately, the Coinage Act defined the dollar as well. In fact, it created an immutable standard based on Spanish antecedents that historically served as the reference point for all US coinage. The Coinage Act of 1792 defined the dollar as a silver coin containing "three hundred and seventy-one grains and four sixteenth parts of a grain (0.7734375 troy ounces) of pure, or four hundred and sixteen grains of standard silver" (~90% Ag,~10% Cu). The content of gold coins was usually adjusted according to this silver dollar standard, which has never changed and is technically still in force today. With the standard set, Congress could finally order the creation of the nation's first coinage, the hallmark of a truly independent and sovereign nation.

The Flowing Hair is born

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Congress tasked engraver Robert Scot with the design of the first U.S. dollar in 1794. Scott, in accordance with federal regulations, placed an eagle on the reverse of the coin. Congress insisted that Scot also add a wreath, which Numismatic News Magazine notes was a classical symbol of victory. The obverse featured a design of Lady Liberty wearing a "liberty cap."

According to the Architect of the Capitol's office, the liberty cap was a combination of two different hats. One was the Phrygian cap, worn in Greece as the symbol of a freeman, and the pileus, worn among emancipated Roman slaves. This piece of headwear became popular in America as the symbol of the Revolution and resistance to monarchical rule. Despite its associations with liberty, Congress removed the cap, leaving Lady Liberty hair flowing loosely behind her shoulders. Thus, the coin gained the nickname "the flowing hair dollar."

Although the coin's release should have been an occasion to celebrate, its reception was underwhelming. According to the National Museum of American History, the coins were poorly stamped because the machinery used to make them had been intended for minting half-dollars and other smaller denominations. Furthermore, the obverse die was damaged, so the impression of Lady Liberty was weak and even more poorly done than the eagle of the reverse. As a result, only 1,758 coins were minted, most of which were distributed as souvenirs. By 1795, Congress had pulled the coin from circulation.

Following the precedent

Although the Flowing Hair Dollar was a bit of a fiasco, it set the United States down the long, hard road towards a stable money system. According to the U.S. Mint, the United States had trouble achieving a functional money system in the first 80 or so years of its existence. Often, the precious metals to mint coins were provided by banks, and there was not always enough. When banks received their coins, they preferred the large denominations, although the average person used fractional coins such as dimes and quarters for daily transactions instead of gold eagles or half-eagles. By 1857, the U.S. Mint expanded operations by opening branches across the country. This allowed small change coins to be distributed where they were needed and produce enough coinage to cover the needs of the entire nation.

Although the silver dollar seemed to be working, much of the world had moved to a gold standard. The Coinage Act of 1873 (via the U.S. Mint) demonetized silver. Silver dollars would continue to be erratically issued in the late 19th century, but the standard was now based around gold instead of the old 1792 standard. But even this would not last long, as banking interests and the federal government would soon replace America's precious metal coins with currency.

The end of American coinage

Despite the late-19th century battles over silver, coins were still expected to be made of precious metals, while bills of credit were still redeemable for precious metal. All this changed in 1933, when President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6102 (via the American Presidency Project). Under the order, Americans were to surrender gold coins and certificates and "redeem" them for $20.67 in Federal Reserve notes (via Investopedia). The Gold Reserve Act then transferred all gold to the ownership of the U.S. government. This effectively amounted to theft/confiscation, because as soon as the gold was collected, the price of gold rose from $20.67 to $35, cheating people out of $15.

While Roosevelt's actions were questionable enough, the worst was the long-term effect. Private ownership of gold over $100 was banned outside of commercial or artistic uses, with the exception of rare coins. Individuals, banks, and the U.S. Treasury were forbidden from converting Federal Reserve notes to gold. Thus, gold was no longer money, but a commodity. The first nail in the United States' monetary system had been driven in.

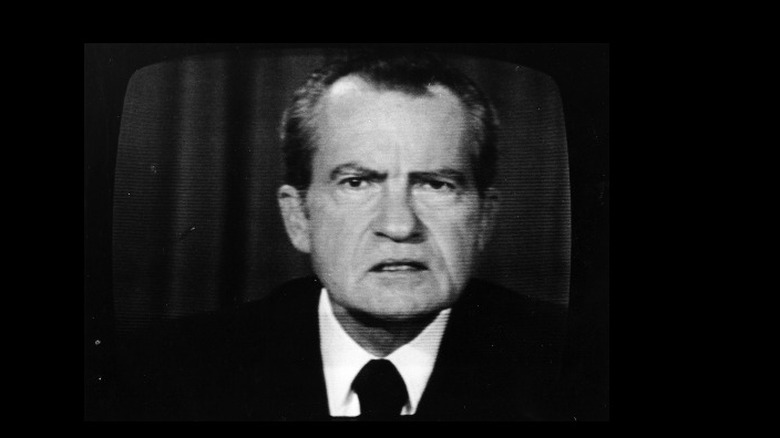

The birth of fiat

Although gold coins were melted down and converted into bars, silver continued to circulate. The U.S. Treasury emitted silver certificates redeemable in silver, most recently under Executive Order 11110 during the Kennedy Administration. Dimes, quarters, and half-dollars remained 90% silver. This all changed on November 22, 1963, when President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed on a visit to Dallas. His VP, Lyndon Johnson, took over.

In 1965, Johnson signed another coinage act which removed silver from U.S. coinage and replaced it with base metals, although it took a few years to implement. Without silver to give it value, coins could now be debased too. This was the second nail in the coffin. Now, the dollar's value was dependent solely on its tenuous link to gold, which would be severed for good six years later.

The final nail came in 1971. Although Congress had banned gold convertibility in 1934, it was still possible for foreign nations holding dollars in reserve to exchange for gold held in US reserves. According to Bloomberg, the prospect of a gold run threatened to drain America's gold reserves. In response, Nixon slammed the gold window shut, officially ending the dollar's convertibility to gold completely. The dollar became a fiat currency backed by government diktat and debt, making it easy to debase through printing. The storied tradition of American bullion begun in 1794 with the Flowing Hair dollar had come to an end and the Founders' greatest fear had come true.