The Untold Truth Of Taxidermy

Although some taxidermists today attribute the origin of taxidermy to Egyptian mummification, there are significant differences between the two. While both mummification and taxidermy are both performed on a body after death, mummification isn't concerned with a lifelike appearance. Taxidermy, on the other hand, not only works towards a lifelike appearance, but is also intended for display. This motivation towards exhibition ultimately distinguishes taxidermy from mummification as its own form of engagement with a dead body.

Arising in Europe, taxidermy soon spread to the United States, but the animals collected would come from every far-reaching corner of the world. And on at least one occasion, taxidermists threatened to extinguish entire species.

While taxidermy is no longer as popular as it was in its heyday, some people are trying to resurrect taxidermy as a conservationist technique. Paleontologist Michael Novacek believes that amalgamating taxidermy and conversation "can preserve nature's legacy." But what of taxidermy's own legacy? This is the untold truth of taxidermy.

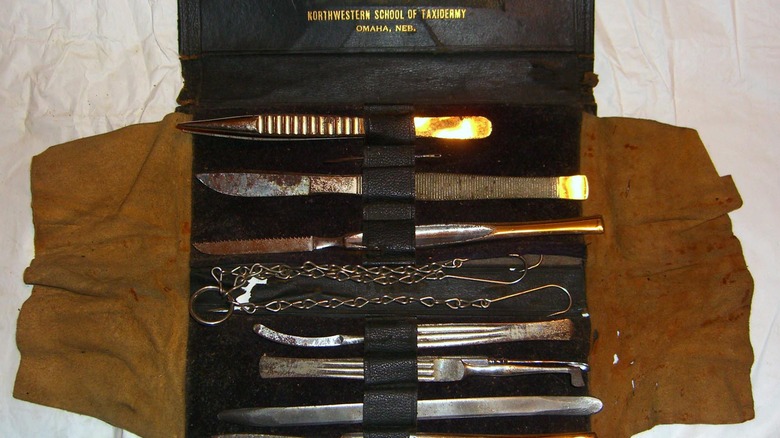

Methods for taxidermy

Taxidermy is the preparation of the skin of an animal so that it can be preserved for display. Initially, taxidermied creations were called "stuffing," likely because it's how many of them were created. According to "Taxidermy Vol. 12," after the animal was skinned, its skin would be stuffed with "straw, excelsior [shavings], or other similar material until it looked something like the living animal." However, this method is no longer used, and, instead, most taxidermists try to make the taxidermied creature appear "as lifelike as possible."

Nowadays, there are multiple main methods for taxidermy: traditional skin-mounts, freeze-dried mounts, and study skins. Animal Family writes that traditional skin-mounts typically use fresh skin, which is "immediately preserved or tanned" to prevent decay. The mounts may be made of wood, bound wool, or wire frames, but the original bones may also be used. With freeze-dried mounts, the creature is entirely frozen, and after its internal organs are removed, it's positioned into its final pose. Afterwards, a machine dehydrates the body using vacuum pressure and cold. This can take up to several months to do properly in order to avoid affecting the creature's appearance. In addition, this type of taxidermy requires upkeep. Study skins are primarily concerned with "scientific study" rather than "showcasing the animal." And since preservation is the main goal, the skin will be preserved using natural materials like cedar dust instead of chemicals. The body is typically stuffed with cotton or acid-free tissue to maintain the original shape.

Taxidermy and conquest

Taxidermy originated in Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries, coming directly out of European conquest and colonization. Traders brought back animals from Africa, Asia, and the Americas to be preserved and collected primarily by rich people in their "cabinets of curiosities," according to Smithsonian Magazine. As Pauline Wakeham notes in "Taxidermic Signs," taxidermy is "a product of the colonial enterprise."

One of the first documented attempts of taxidermy comes from the 1500s, when a wealthy Dutch businessman tried to "retain in deceased form" some birds that suffocated in transport from the East Indies. Other early examples include a crocodile from Egypt and a dodo bird from Mauritius. Taxidermy soon became a key component for Carl Linnaeus' classification system as he sent his students around the world to collect and mount samples in the 1700s. Many taxidermied creatures were especially valued if the skin came from an animal recently killed in its country of origin, "as if an element of its environment travelled with the creature," according to History Today.

In this way, taxidermy became a way to not only collect nature, but to legitimize it through conquest towards a "systematization of nature." In "Imperial Eyes," Mary Louise Pratt writes that "The eighteenth-century classificatory systems created the task of locating every species on the planet, extracting it from its particular, arbitrary surroundings (the chaos), and placing it in its appropriate spot in the system (the order — book, collection, or garden) with its new written, secular European name."

The confusing platypus

When the first reports of a platypus came back to Europe, no one could believe that such a creature actually existed in the world. According to "The Art of Taxidermy" by Jane Eastoe, the platypus was first encountered in Australia in 1798. Afterwards, a drawing of the full animal was sent back to Britain along with its pelt. However, upon seeing the creature, "scientists decreed it an improbable taxidermy hoax."

In 1799, a full platypus was brought to biologist George Shaw in England preserved in alcohol. Atlas Obscura writes that Shaw proceeded to cut the beak off the platypus, convinced that he would find the stitching of an expert taxidermist. And despite finding no evidence that the creature was a fake, Shaw still couldn't believe that it was real. In "The Naturalist's Miscellany," Shaw would write that the platypus "naturally excites the idea of some deceptive preparation by artificial means." This wouldn't have been the first time that someone tried to convince the scientific community of a creature's legitimacy. But although the platypus was as genuine as they come, people like anatomist Robert Knox called the creature a "freak imposture."

In an attempt to convince the European scientists of the platypus's authenticity, during the 1830s and '40s, "literally thousands of preserved and stuffed platypus and their uteri were shipped back to Britain for research. It's a miracle they still survive today after such slaughter" (via International Science and National Scientific Identity).

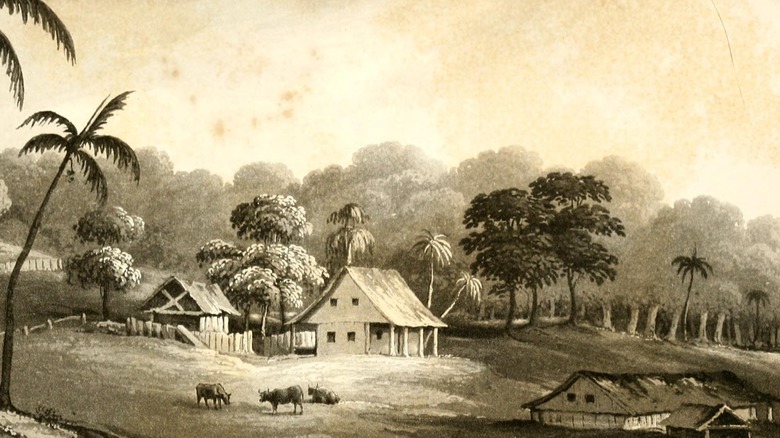

How did Darwin learn taxidermy?

Charles Darwin became famous with the help of the Galapagos birds he taxidermied and used as evidence for his theory of evolution, but without the tutelage of John Edmonstone, who knows if Darwin's birds would've been as convincing. According to Think Africa, Edmonstone was born into enslavement on a timber plantation in Demerara, Guyana, and his enslaver was Charles Edmonstone, from whom Edmonstone got his last name. The naturalist Charles Waterton visited the plantation numerous times and went on expeditions to catch and taxidermy birds. Edmonstone accompanied Waterton several times and learned from Waterton how to do taxidermy. Atlas Obscura writes that due to the humidity of the jungle, they had to "skin and stuff creatures on the spot, before they had a chance to decay."

The U.K. Natural History Museum writes that Edmonstone went with his enslaver to Scotland in 1817, and because enslavement was outlawed in Britain, Edmonstone was effectively a free person upon entering Scotland. Before long, Edmonstone was teaching taxidermy at the University of Edinburgh and making specimens for its zoological museum. And in 1826, he ended up with Darwin as an apprentice after the young medical student realized that he had no interest in medical school. For an hour a day every day for two months, Edmonstone tutored Darwin on how to taxidermy birds.

Unfortunately, little is known about Edmonstone's personal life or career, and he's historically been treated as a "footnote in Darwin's biography."

London's Great Exhibition of 1851

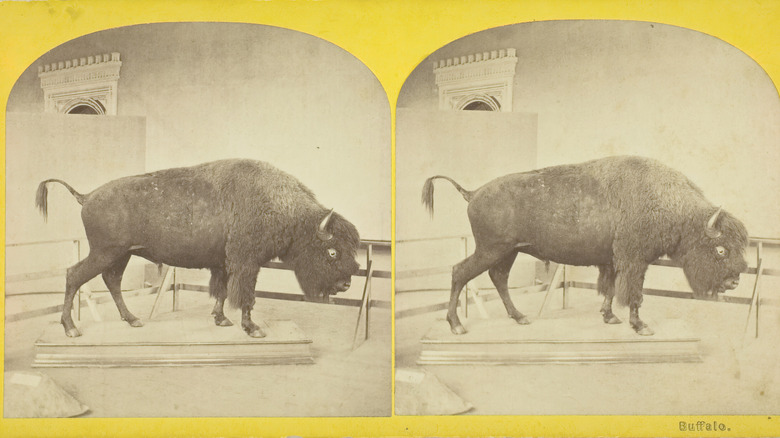

Housed in Hyde Park in London, the Great Exhibition of 1851, also known as the Crystal Palace Exhibition, was partly created in order to display industrial advancements to the public. But as Atlas Obscura notes, it was also a "public relations device to boost the image of British superiority."

And without fail, taxidermy was numerously represented at London's Great Exhibition of 1851. For the centerpiece of the India display, which was still under British company control but would come under the Crown's rule in seven years, an elephant was demanded. Although an old elephant skin was found at the Saffron Walden Museum, it was a far cry from an Asian elephant. According to History Today, the elephant that was used came from South Africa in the 1830s and was an African elephant rather than an Asian elephant. As a result, the back was longer and wasn't the correct shape for the howdah that was to be strapped onto its back. But the display was put up regardless and "nobody seemed to mind that this African skin was found in Essex and exhibited in London as an Indian animal."

In addition to the elephant, the dioramas by German taxidermist Hermann Ploucquet also "enraptured the Victorians." Using taxidermied animals such as mice, rabbits, and hedgehogs, Ploucquet created action scenes from folk tales as well as popular paintings of the time, and the public was delighted by his dioramas. Even Queen Victoria described them as "really marvelous."

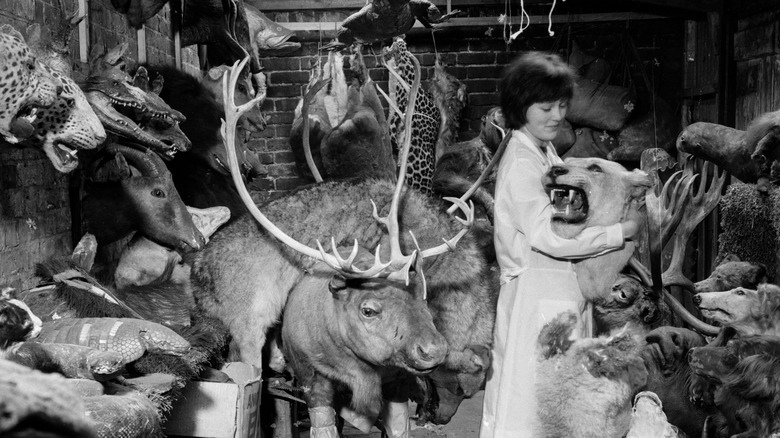

Paired with Victorian morbidity

As more and more exhibitions displayed taxidermied animals in 1871, 1886, and 1887, Victorians became obsessed with taxidermy. The Victorian era would become known as the "golden age of taxidermy," and stuffed birds could be found in most parlors in Britain. Many taxidermied creatures would have even gone from being a pet to a household ornament to a museum exhibit.

The creatures were propped into poses or "integrated into human society" as a chair or a lamp. Some women even wore hummingbird earrings. In "Beastly Possessions," Sarah Amato writes that "these objects reflected the Victorian and Edwardian belief that animals should be useful to humans, even in death." But even if the animal wasn't tied to an appliance, they were twisted into morbid manifestations, some of which are said to contain "the perfect tension between the cute and the perverse," according to Joanna Ebenstein, co-founder and creative director of the Morbid Anatomy Museum, per BBC.

One of the most popular examples of this is Walter Potter's "The Kitten Wedding." Featuring a number of kittens dressed up to a wedding in human-style, "The Kitten Wedding" was one of Potter's many anthropomorphic taxidermy creations. His collection ended up becoming quite famous and first opened as a museum in a pub's summer house in 1861. By the 20th century, it was an incredibly popular tourist destination.

Human taxidermy

Although taxidermy is typically reserved for animals, the colonial mindset of possession allowed for the practice to be extended towards people as well. In 1831, Jules and Édouard Verreaux went to Cape Town in South Africa, then part of the British Empire, where they attended the funeral of a person who was part of the Sān people. The Guardian writes that after the funeral, "the Verreaux brothers dug up the man's body and had him stuffed, mounted and shipped back to France." Known as "El Negro," the Sān person was displayed at fairs in Paris as late as 1872. And after passing through different hands, he ended up as an exhibit in the Darder Museum of Natural History in Banyoles as "Bushman of the Kalahari."

In "Disorientations," Susan Martin-Márquez writes that Alphonse Arcelin was one of the first to publicly express outrage about the taxidermied body in 1991. He also informed the International Olympic Committee of the taxidermied body, and, as a result, the museum was closed during the 1992 Barcelona Games. After almost a decade of protests, the body was finally repatriated.

However, despite evidence that the Sān person was from South Africa, the body was repatriated to Botswana because the South African government didn't ask for repatriation. And as a final insult, all that was returned were the skull and bones, since Spanish museum professionals took it upon themselves to "scrap[e] the skin from the bones," according to "Witnesses to History."

A taxidermist in every town

The public's desire for taxidermy was so great that taxidermy as a trade flourished in both Europe and the United States. In 1891 in London, the census lists 369 taxidermists, and rural villages also included taxidermists within their ranks. According to Smithsonian Magazine, this essentially amounted to "one taxidermist for every 15,000 Londoners." The taxidermist was as much of an everyday job as being a butcher or a barber. In the United States as well, most large urban areas "had at least one taxidermy shop," John Parascandola writes in "King of Poisons."

However, the exhibition of taxidermy occurred largely in Europe. Although the Society of American Taxidermists was founded in 1880, they only held three general exhibitions before breaking up due to a "lack of cooperation among the taxidermists of the day," according to "Taxidermy Vol. 8." But although there weren't yearly exhibitions like the ones in England, this isn't to say that taxidermied creatures weren't seen by the public.

Many museums in the United States, like the American Museum of Natural History in New York, created large, elaborate, and permanent diorama exhibits in which to display their taxidermied creatures. Taxidermy pervaded so many aspects of social life that even in the Hardy Boys' 1945 adventure "The Short-Wave Mystery," the best friend of the detectives, Chet Morton, "dabbl[es] in taxidermy."

The use of arsenic

Arsenic started being used in taxidermy as early as the 18th century, and its use continued up until the 1980s. But according to Radford University, arsenic's use as a preservative started as early as the fifth century B.C. when it was "placed in the underside of the skin of an animal to help preserve and protect it from insects."

Jean-Baptiste Bécœur, a French ornithologist, discovered arsenic's potential towards taxidermy in the mid-18th century, and he became known for his arsenical soap, which museums used around the world (via "Conservation of Leather and Related Materials"). Taxidermists also mixed arsenic with things like aloe and cinnamon to make the taxidermied creatures smell better.

Exposure to arsenic can result in arsenic poisoning, and although the use of arsenic in taxidermy has been banned since 1980, gloves must be worn when handling taxidermied creatures made before 1980. And although mercury was also used as a preservative, the Indiana Historical Society writes that it's best to assume that any taxidermy made before 1980 may contain arsenic. In 2009, two staff members at the Museum Victoria required medical attention after working with older taxidermied creatures that were later found to have high levels of arsenic. Thankfully, both workers were fine in the end. The Age writes that the arsenic in the taxidermied creatures only poses a health risk if touched, so despite having hundreds of creatures that "likely still contain arsenic," there's little concern among museums as long as the proper precautions are taken.

Taxidermied eagles are special

In 1940, the United States Congress passed the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, which made it illegal to "possess, sell, hunt, or even offer to sell, hunt or possess bald eagles." This act protected not only living eagles, but extended its protection to their feathers, nests, eggs, or even body parts, according to Michigan State University. This meant that even taxidermied eagles fell under the protections of the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act. The penalty for violating the act can be $5,000.

The Indiana Historical Society writes if a museum wants to display a taxidermy eagle — or even a single part of it — they must first contact the National Eagle Repository. If the National Eagle Repository agrees, then the museum can receive a special permit in order to display the taxidermied eagle or its remains.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, the law also stipulates that members of Indigenous groups in the United States, including the Osage, the Zuni and the Arapaho, can also get a permit to access golden eagle and bald eagle feathers. This is where the National Eagle Repository comes in. They are the ones who send eagle feathers to Indigenous groups who need them for religious and cultural ceremonies. Between 1996 and 2015, the repository increased their number of fulfilled orders from 2,400 to 4,500 per year.

Taxidermy today

Although the Victorian era was called the golden age of taxidermy, taxidermy is seeing a revival in the 21st century. The World Taxidermy & Fish Carving Championships (WTC) is held every year in the United States in Springfield, Missouri, and in 2015, there were over 1,200 attendees. According to Smithsonian Magazine, taxidermists can also find jobs restoring museum displays or even work on extracting DNA from preserved bodies.

Taxidermied creatures also found fame as unusual and humorous images of taxidermy spread across the internet. Memes like "Stoned Fox" came into existence after Adele Morse created a taxidermied fox with a spaced-out face in 2012. By 2013, "Stoned Fox" was named Meme of the Year. And Stoned Fox isn't the only meme to come out of a taxidermied creature. "Persian Cat Room Guardian," "Depression Dog," and "Sphere Cow" are all memes that are based on a taxidermied creature, according to Know Your Meme.