Things You Get Wrong About The Puritans

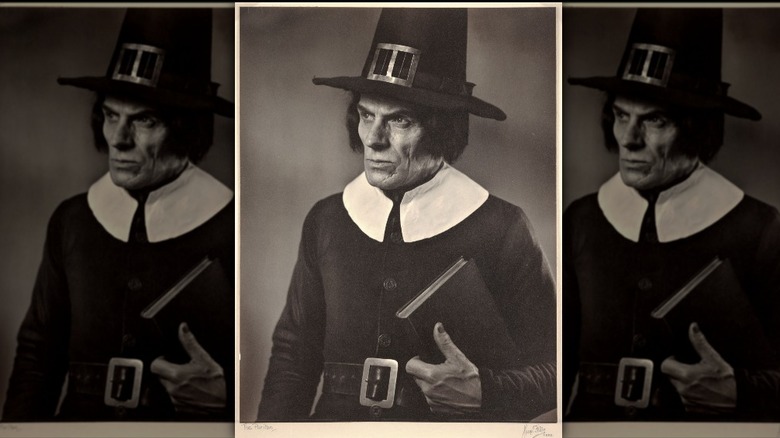

How did the first settlers in America celebrate Christmas? According to the Week, not at all. America's earliest settlers were members of the Calvinist Puritan denomination that hated Christmas and banned it, scolding their children from participating in it at all (as pictured above). This is just one example that has given the Puritans a bad reputation in American popular imagination, even among other Protestants. They have been seen as strict theocrats, who, to paraphrase the words of journalist H.L. Mencken, were haunted by the fear that "someone, somewhere, might be happy."

But was this reputation deserved? Probably not, as the truth behind the Puritans, as usual, was more complicated and nuanced. While New England Puritan society did enforce strict social mores, many of the negative stereotypes arose later, are distortions of the historical record, or arise from judging the Puritans using modern standards. In reality, the Puritans were crucial to the creation of the United States' first schools and colleges. They found joy in life's simple pleasures and, although they railed against excess, were not against fun. Although their society did not last, they left their mark upon society in the form of the United States Constitution, which according to the First Amendment Encyclopedia, owes a great debt to the Puritan intellectual tradition. Here are some common misconceptions debunked.

The Pilgrims were Puritans

Who were the Puritans? Popular American history equates them with the Pilgrims, who made landfall at Plymouth Rock in 1620 and celebrated the first Thanksgiving (really a harvest festival) there. Newsweek notes that although the two groups had the same general beliefs, they differed in their attitudes of resolving the issue of Catholic holdovers within the Church of England .

The Pilgrims were known in their day as "Separatists." According to PBS' American Experience, the Church of England's opulent liturgies and hierarchical structure with wealthy and influential bishops at the top irked many Puritans. The ecclesiastical courts suffered from deep-running corruption, undoubtedly due to the church's intimate connection to the state through its head, the English king. The Separatists, according to British Heritage, wanted to do away with these Catholic trappings. But in 1605, they broke with the Church of England and settled in the Netherlands for a few years. Eventually, a few returned to England and went on to America.

The Puritans, like the Separatists, wanted to "purify" (hence their name) the Church of England of Catholic remnants. In fact, as the SBTS notes, the name was originally a slur. But according to the Library of Congress, the Puritans hoped to accomplish this through internal reform of the Church of England, not by destroying or leaving it. For this, the Puritan clergy was persecuted, although much of it was political. Their solution was to leave for America and establish their own churches with minimal hierarchy that the Church of England could emulate.

They were fleeing religious persecution

According to Christian History Institute, a major myth posits that Puritan immigration to America stemmed from persecution. This myth is partially true. As the Library of Congress notes, the Puritan clergy, who were officially part of the Church of England, were sometimes brutally punished for falling out of line. High officials with Puritan sympathies, according to British Heritage, lost their jobs and often their property, too. According to the National Archives, however, this persecution had a political dimension. Criticism of the Church of England equated to the crime of lèse majesté, since the king was the church's head. Puritan ministers, as Church of England clerics, per the royal website, swore to uphold royal authority. If they criticized the church, they criticized the king, violated their oaths, and committed treason. Thus, Puritan ministers had good reason to leave England. But not so much for ordinary people.

Christian History Institute notes that many Puritans followed their ministers to America to partake in a grand experiment. They envisioned a new society in the New World that is best captured in Governor John Winthrop's 1630 sermon en route to Massachusetts Bay. In his Exodus-inspired sermon, Winthrop (pictured above) exhorted his followers to build a "city on a hill," a beacon to guide the world to God. Should the Puritans stray, God would punish them as an example to the world. Witnhrop's followers and their successors must have believed in the vision to risk everything in a new, foreign land. Little did they know, their "city on a hill" would sow the first seeds of a new nation.

They sought to establish religious liberty

The Puritans did not seek to build a religiously free society. WNET Thirteen notes that toleration of other faiths was unknown and illogical to them. After all, a righteous "city on a hill" could not be a beacon to the world if it tolerated falsehood. Such an attitude would incur divine wrath. Instead, Puritans sought to overthrow non-Puritan governments whenever the opportunity arose.

Massachusetts Bay and Maryland illustrate the Puritan attitude towards other faiths, especially Catholics. According to Boston Magazine, the city ironically known as an Irish Catholic bastion originally considered Catholics "devils" and the Pope the antichrist. Catholic priests were banned from Massachusetts on the pain of banishment for the first offense and death for repeat offenders, although the law's effectiveness was questionable.

Massachusetts was built by Puritans for Puritans. But Maryland was a different story. As History notes, Maryland was chartered as a colony for Catholics to worship freely. Despite the colony's Catholic identity, the 1649 Act of Toleration gave Protestants religious freedom and, according to Christianity Magazine, even banned religious slurs, including the word "Puritan." But, as the State of Maryland notes, a small Catholic elite connected with the founding Calvert family lorded over a steadily-increasing Protestant population. Fed up with Catholic dominance, a Puritan named John Coode assembled a militia and overthrew the Catholic-dominated government. Coode's rebels, according to the Bill of Rights Institute, promptly outlawed Catholicism and drove it underground. Hardly a paragon of religious freedom.

They hated Native Americans

European and Native American relations are uncritically and one-dimensionally portrayed in contemporary historiography. The natives are victims, and the Europeans as hateful oppressors. But the reality is more complicated, and the Puritans were in the middle of it all. Relations between Puritans and Native Americans were mixed. The Puritans did not hate Native Americans. They did, however, disapprove of Native American religion and sought the conversion of the New England tribes to Christianity. According to Dartmouth College, Eleazer Whitelock founded the school in order for this very purpose. According to VOA, around a quarter of New England's Native population embraced Christianity.

Despite Christianity's modest success among the tribes, relations between Native Americans and Puritans were tense. But the animus appears political and economic, not racial. According to Connecticut History, the expanding Puritan colonies needed more land to support their populations, while the Wampanoag leader Metacom sought to check them. But the spark was ironically the death of the Christian Native American interpreter John Sassamon. According to American Antiquarian, he warned the New England colonies of an impending Wampanoag attack and was murdered, likely by his own people, as a traitor. The subsequent execution of three of Metacom's men ignited King Philip's War, which saw massacres of Natives and Europeans alike. But even this conflict was not clear-cut, since the Pequot and Mohegan tribes allied with the colonists. As the alliances of the war show, Puritans did not seek the extermination of Natives, but rather sought to convert them and civilize them according to their own standards. They reserved their hatred for the popish antichrist in Rome and their archenemies, the Quakers (via LOC).

They were inflexible and dogmatic

The narrative of a "city on a hill" suggests that in order to keep God's ways in this beacon to the world, Puritans had to inflexibly follow their theology to the letter. In certain matters, such as public morals, they were quite strict. But religions often bend their rules to accommodate the ordinary people that make up their congregations. The Puritans were no different. As the numbers of church rolls declined in the late 17th century, they removed barriers to church membership previously thought as sacrosanct.

According to the National Humanities Center, baptized Puritans entered full communion with the Congregationalist Church through conversion. In practice, it entailed a public account of conversion before the congregation. Now, according to the book "Congregationalists in America," the number of conversions began dropping among the colonists' children. So when a grandfather sought to baptize his grandson in 1634, the church denied him because the parents were not converted. The subsequent split between advocates for closed and open membership triggered a debate on Puritan identity. Open membership without conversion would place Puritanism on par with the Church of England, which they sought to recreate, or even worse, the Catholic Church. But according to Britannica, declining numbers forced the clergy's hand and they voted in 1657 to pass the Halfway Covenant. This compromise extended baptism to all children of baptized (but not converted) parents and allowed them to be partial church members, a sign that the denomination was not constrained by its rules if it needed to adapt.

The Puritan colonies were theocracies

Theocracy is a dirty word today — and a misused one. Professor John Rees, writing in the online journal e-International Relations, notes that it is often a slur of anti-religion activists to silence their political opponents. According to the Cambridge Dictionary, a theocracy is a government run by religious leaders. Partnership of Historic Bostons notes that the Puritan colonies are referred to as such throughout literature (The First Amendment Encyclopedia even does so). But they were not theocracies in the proper sense of the word.

The New England colonies had civil governments, a tradition that probably began with the explicit rejection of English theocracy. In England, the king was the highest religious and civil authority. Bishops served as judges and ministers, a marriage that encouraged church corruption. Excommunicants lost their careers, possessions, and lives. In contrast, New England rejected theocratic government. Puritan ministers were explicitly forbidden from holding any political office and could not deprive excommunicants of their political rights or property.

Although Puritan society was not theocratic, it did believe in secular enforcement of Christian morality. The First Amendment Encyclopedia correctly states that the civil authorities of New England were expected to punish public sinners and extirpate heresy from society. After all, they were building a beacon of light for the world to follow. But this was not theocracy; it was a government informed by religious tenets.

They were tee-totalers

"If Puritans were still around, would alcohol be considered a drug?" This headline graces a 1994 story in the Orlando Sentinel. Many would probably answer yes, revealing a common but incorrect notion that Puritans were tee-totaling killjoys. But if the Puritans were still around, there probably would be no minimum age law to drink. As the BBC notes, the Puritans, like most people of the American colonies, were drinkers who loved their alcohol.

According to the U.S. National Archives' Spirited Republic exhibit, the Puritan minister and president of Harvard Increase Mather, called alcohol a "good creature of God." In keeping with his sentiment, American colonists of all faiths drank with every meal, and children often started their day with a dram of whiskey. This attitude to alcohol was a fairly healthy one, stressing moderation of good things and avoidance of excess and self-indulgence. From a health perspective, it made sense too. According to U.S. History Scene, alcohol was safer than possibly contaminated water.

Drunkenness was another story. Puritanism didn't only scorn drunkenness; it was a criminal offense. According to the New England Historical Society, certain crimes were punished by having the guilty party wear the first letter of the offense in question (hence "The Scarlet Letter" and "A for adultery"). Thus, drunks were forced to wear a prominent "D" on their clothing to shame them for their behavior. This was supposedly the harsh punishment. The lesser punishment was wearing a sign on one's back that said "Drunkard."

They were closed-minded

Arthur Miller's 1953 play "The Crucible" depicted Puritan New England as a closed-minded, zealous society with little regard for reason. Although Miller's play was not a faithful representation of 17th-century New England life, Patheos notes that American schools portray it as such. But American students also dream of attending top universities, including Harvard (pictured above), Yale, and Dartmouth. Ironic that Puritans founded all three schools.

Colleges such as Harvard were the pride of New England. But it was a hard road to get in. The Puritan system expected college-bound students to master the Greco-Latin classics apart from the "three R's". According to Memoria Press, Puritan grammar schools (which at the time meant "Latin school"), drilled students in classical languages as early as age 7. Cotton Mather, son of the famous pastor and Harvard president Increase Mather, was fluent in Latin by age 12 and graduated Harvard at 15, a testament to his abilities and the excellence of Puritan education. He mastered logic and rhetoric, too, and believed that faith and reason were always in dialogue, not in contradiction. Certainly not very "Puritanical" of him.

Religion explains the Puritan emphasis on education, which sought to create faithful, exemplary citizens who could outwit Satan. According to the New England Historical Society, ignorance made sinners. The Old Deluder (Satan) could easily tempt the ignorant with his lies. Thus, "the idle fool is whipped at school" for his own good and families contributed "college corn" to support Harvard. Regardless of intention, the system worked. According to Freedom Trail, of the Declaration of Independence's signatories, five were products of the Puritan intellectual tradition.

They hated sex

Returning to social mores, Merriam-Webster defines "puritanical" as something pertaining to "rigid morality." Among the synonyms are "straightlaced" and "prudish," which, in popular parlance, describe people who reject open sex and therefore, must hate sex. But the definition is based on a false premise. The Puritans loved sex and wrote about it, too.

Puritan society held prudish views towards pre-marital sex and homosexuality. According to Boston Magazine, these were crimes of fornication and unnatural relations, respectively. As seen in Nathaniel Hawthorne's "Scarlet Letter," fornicators were publicly humiliated, while homosexuality was a capital offense. But marital sex was a bonding experience and a duty to be enjoyed. According to Desiring God, Puritan couples were expected to channel their passions into a loving, Godly, and, yes, passionate sexual relationship. As a result, according to The Beauty and Glory of Christian Living, families averaged eight children or more.

The Puritans openly expressed their love of proper sex in writing. Governor John Winthrop of Massachusetts Bay passionately conveyed his desire for "a more familiar connection" with his wife in their letters. Although G-rated to modern observers, editors redacted his letters as late as the early 20th century. Puritan poet Anne Bradstreet pined for her husband's "warmth," which melted the "frigid colds." In his absence, she turned to "those fruits which through [his] heat [she] bore" her children. This open talk of sex was scandalous between unmarried people, but between spouses, it was normal and certainly not sinful.

They were paranoid witch hunters

Puritanism is synonymous with witch hunting. The Salem Witch Trials of 1692 epitomize Puritan zealotry and paranoia in popular imagination. But the journal Pneuma Review writes that the association of Puritanism with witch hunting is false. Rather, Salem provided fodder for the "devil's victory" as the trials' historical context was distorted and presented as something uniquely Puritan. Yet, virtually all 17th-century European societies believed in witchcraft, which, in the Old World, was subject to mob justice. But according to Historic Bostons, accused witches (men and women) in Puritan New England had the right to an investigation and trial if the evidence warranted one. In practice, the vast majority of accusations were dismissed.

The Salem panic was anomalous, and according to History, the reaction of some members of the Puritan clergy was remarkably measured, even though they all believed in witchcraft. Increase Mather opposed aggressive prosecution whose only evidence was dreams. When the trials went ahead against his advice, Mather (via the Bill of Rights Institute) famously declared that it was better for "ten suspected witches should escape, than that one innocent person should be condemned." His words birthed the American principle of presumption of innocence.

Excluding Salem, the numbers don't lie. Witch paranoia in New England was rare. Only 65 trials and 16 executions out of a population of approximately 100,000 are attested between 1638 and 1697.

They always wore black

The stereotypical Puritan man was depicted wearing all-black and a hat with a buckle on it. Black seems like a modest, neutral color, which makes sense in a society that valued modesty and eschewed ostentatiousness. But contrary to tropes, the Puritans did not always wear black. In fact, black was considered immodest because it was expensive and was reserved for high-status individuals. Everyday Puritan dress came in a variety of colors drawn from the English countryside.

According to Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America, the Puritans simply adopted the folk dress of their home regions. For most, this was the dress of England's East Anglia region. The East Anglia region was famous for its "sadd colors," even before the appearance of Puritanism. Such colors included russet, various dark shades of green, purple, and liver. Such clothes were loose-fitting, modest in shade, and did not arouse the sexual passions of others.

According to the New England Historical Society, Puritan fashion was a reaction to the courtly fashions of the English nobility. English haute-couture was designed to flaunt both the wearer's physique and wealth. To prevent the spread of immodesty and ostentatiousness, the Puritan colonies had a number of sumptuary laws on the books, which according to Elizabethan, were laws that restricted the wearing of certain types of clothing. Generally speaking, gold and silver lace and silk were initially forbidden, although exceptions were unsurprisingly made for the rich and powerful. As Puritanism's influence waned, New Englanders discarded modesty in favor of European haute-couture.