The Untold Truth Of Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer

The most widely known and celebrated fantastical, mythical figure associated with Christmas lore, second only to his kindly boss Santa Claus, of course, is Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. The most famous reindeer of all, he has a shiny red nose that at first branded him a freak of nature and pariah amongst all of the other reindeer in Santa's employ, until the man in the big red suit called upon Rudolph to use his unique gift and trait to guide his sleigh through a woefully stormy Christmas Eve, thus saving Christmas for all the boys and girls the world over.

That's the stuff of legend, and Rudolph is one of the most enduring pillars of modern mythology, his moving and inspiring story a beloved part of Christmas for young and old alike, told eternally through storybooks, movies, an indefatigable television special, and one of the most popular Christmas pop songs ever recorded. Here's everything you may not recall about the reindeer who went down in history: Rudolph, the red-nosed one.

Rudolph was born amidst tragedy

In early 1939, according to NPR, a manager at the Chicago offices of Montgomery Ward department stores wanted to entice customers for the upcoming holiday season. The idea: Give away a children's book, produced in-house. The employee tasked with creating the storybook: a catalog copy writer in the advertising department named Robert L. May, who had a knack for telling funny stories and reciting limericks at office parties. May somewhat welcomed the assignment, a respite from the usual drudgery, and which was more in line with what he'd actually wanted to do. "Instead of writing the great American novel, as I'd once hoped, I was describing men's white shirts," he recalled in a 1963 interview (via Time).

May's life was in disarray at the time he was asked to write a Christmas book he didn't really feel like writing. "My wife was suffering from a long illness and I didn't feel very festive," he'd later tell the Gettysburg Times. May's wife died later that year, leaving him the single parent of a five-year-old daughter and in serious medical debt. His boss at Montgomery Ward, retail sales manager H.E. MacDonald, offered to pull May off the Christmas book, but he refused. May saw the project through, and it was wildly successful — in the holiday season of 1939, Montgomery Ward's American outlets handed out more than two million books written by May, the tale of an unliked underdog who does a monumental favor for Santa Claus.

Rudolph was inspired by the author's self image and fog

During the early stages of devising that Christmas storybook, Montgomery Ward copywriter Robert L. May quickly got the idea to write about reindeer because they're so strongly associated with Santa Claus and because his daughter personally loved them, fascinated by a group of the animals at Chicago's Lincoln Park Zoo, according to Time. As Santa's reindeer already had names (Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Donner, Blitzen), May invented a new one, and wanted to give him an "R" name, for the sake of alliteration, and rejected Rodney, Roddy, Rudy, Rollo, Roland, Reginald, and Romeo (per NPR), before settling on Rudolph. According to a 1963 interview, May thought Rudolph "rolled off the tongue nicely."

The name Rudolph described a lonely outcast of a reindeer, one shunned by all the other reindeer because of his glowing red nose. "It was his opinion of himself that gave rise to Rudolph, I think," May's daughter, Barbara May Lewis, told NPR. The author and copywriter considered himself a nerdy misfit who struggled to socialize. The metaphor manifested as a big red nose when May, staring out of his office window at the dense fog rising up from Lake Michigan and enveloping downtown Chicago, thought about how Santa Claus would have a tough time flying his sleigh through all that. Then, May thought, what if a reindeer had a naturally helpful nose to light the way for the magical sleigh.

How Rudolph got his look

In 1939, Robert L. May turned in an early draft of what would become "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer" to H.E. MacDonald, the head of Montgomery Ward retail sales who'd asked him to write a customer premium storybook. May only handed in the text, and the supervisor bluntly didn't care for what the catalog copywriter had put on the page. "Can't you come up with anything better?" May recalled to the Gettysburg Times in 1975 (via NPR). According to Ronald D. Lankford Jr.'s "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer: An American Hero," MacDonald specifically didn't like the idea that the major and plot-driving characteristic of the main character in a book meant for children sported a red nose, because, at the time, such a physical trait was visual shorthand for drunkenness.

To separate Rudolph from his red nose would ruin the story, so May set to work on proving to MacDonald that what he had was viable. He enlisted Denver Gillen, a friend and colleague who worked in the Ward's art department, to draw some adorable sketches of deer to accompany the manuscript. May, his young daughter Barbara, and Gillen gathered one Saturday at Chicago's Lincoln Park Zoo to observe the deer. May rejected Gillen's first sketches — one reindeer looked too old, another's antlers were too much. Finally, some drawings of Rudolph looking extra small (with an extra-big nose) won over MacDonald, and the book could proceed.

Montgomery Ward abandoned Rudolph

Because of "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer," the book, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, the bit of Christmas iconography, became a cultural phenomenon, instantly absorbed into the general celebration of the holidays. Meanwhile, the character's creator, Robert L. May didn't see any notable financial gain despite having a book with millions of copies in circulation — he'd written "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer" as a work assignment, so Montgomery Ward controlled the rights (and enjoyed any benefits) and simply continued to employ May as a copywriter for its catalogs, according to NPR. However, just after the end of World War II, Ward's CEO Sewell Avery gave up the rights to everything Rudolph, handing them over to May.

"It was just this silly little almost booklet," May's daughter, Barbara May Lewis told NPR, convinced that the department store chain thought the character had fulfilled or worn out its usefulness as a promotional tool after nearly a decade. May quickly jumped on what he thought was a plum business opportunity, seeking out ways to expand the Rudolph franchise and exploit what he knew was a valuable intellectual property.

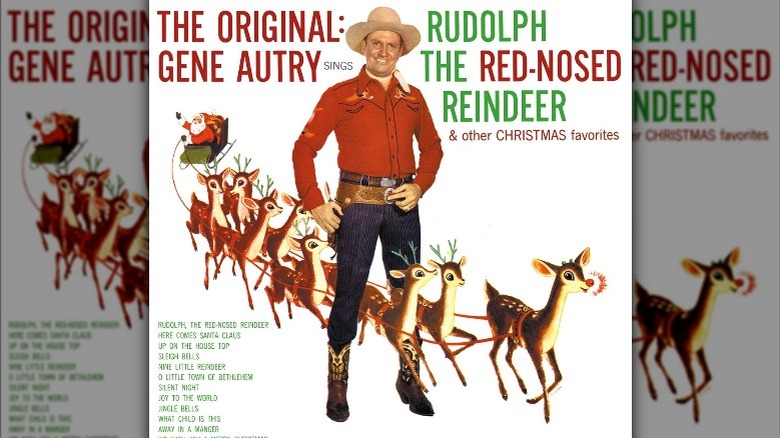

How Rudolph became the subject of a hit song

One of the first ways that Robert L. May sent his creation into other media was with a song. According to Holly George Warren's "Public Cowboy No. 1: The Life and Times of Gene Autry," May's brother-in-law was pop songwriter Johnny Marks, and he allowed him to write a holiday tune about the character, the first version of which apparently wasn't very good. "That song was easily one of the worst songs ever written," Marks recalled. "Then about a year later I was walking down the street when a new melody came to me. It's the only time that ever happened, and I have to admit, it's a great melody." Marks made a demo for label RCA Victor in hopes that Perry Como would record it, but he turned it down, as did other big stars Dinah Shore and Bing Crosby. The demo made its way to country star Gene Autry, who, actively looking for a seasonal follow-up to his Christmas-themed smash hit "Here Comes Santa Claus," agreed to make the song, and he laid down his vocals in 1949.

More than 500 other artists would record "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer," which retells the story from May's book, but Autry's version is the standard. In 1949, it went to #1 on Billboard's pop and country charts, and according to NPR would eventually sell in excess of 25 million copies, making it the second-best-selling single (holiday-themed or otherwise) behind Crosby's "White Christmas."

The origin of the additional, unofficial lyrics to 'Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer'

Almost as memorable and memorized as the lyrics to Johnny Marks' original song, "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer," as made famous by Gene Autry in the first recording of the song in 1949, are the jokey, sneering, alternate lyrics shouted out as punchlines after almost every line in the song. For example, "reindeer" is repeated after the first line, and his nose glows "like a light bulb!" There are regional variations and crude takes, and it's a viral phenomenon that spread long before the internet and in their primitive form, these extra lyrics date back almost as far as the song they parody along the way.

In the mid-1950s, children's and novelty label Cricket Records released a 45 rpm record (per Discogs) of "Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer," credited to Don Janse & His Children's Chorus. The arrangement features children singing on the song, some of whom echo and repeat the lines, one of the first recorded instances of lyrical alterations. Those would evolve over time, and become popularized and solidified in the mainstream with the very first episode of "The Simpsons" in 1989 (pictured). Over the end credits, the extended Simpsons family sings "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer," and Bart and Lisa, to the chagrin of dad Homer, add in off-color lyrical additions.

How the classic Rudolph TV special was made

"Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer" the book came first, which inspired the song, which directly led to a stop-motion animated television special. Produced by stop-motion animation house Videocraft International (later renamed Rankin/Bass after founders Arthur Rankin Jr. and Jules Bass, per CBR), screenwriter Romeo Muller wrote the 47-minute "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer" necessarily bolstering the plot-scant original book and short pop song by adding in a lengthy plot and multiple characters. According to TV Guide, Muller didn't really have a choice but to create elements like the Island of Misfit Toys, Hermey the North Pole elf who really wants to be a dentist, Bumble, Sam the Snowman — he'd intended to pen a more straightforward adaptation of May's book, but when he was writing, he couldn't locate a reference copy.

"Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer," (per the CBC) debuted on NBC on December 6, 1964, and it's been a perpetually rerun holiday special ever since. It's now the longest-running Christmas special of all time, and in 2014, the U.S. Postal Service commemorated its 50th anniversary with a set of postage stamps honoring the stop-motion versions of characters Rudolph, Santa, Hermey, and Bumble.

Scientists have looked into the redness of Rudolph's nose

Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer is deeply embedded in the culture for supposedly saving some Christmas long ago. While the world knows the what of Rudolph, there's always been a question of how and why — how does Rudolph's bright red nose glow so bright, and why does it do that?

In 2012, according to the National Library of Medicine, "The British Medical Journal" published a study that sought to "characterize the functional morphology of the nasal microcirculation in humans in comparison with reindeer," or rather to determine the physiology of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer's red nose. The researchers' thesis: that Rudolph's bright red nose is such because of a denser and more concentrated than usual framework of blood vessels. Scientists set up a study in Tromso, Norway (not far from the real North Pole) and in the Netherlands and observed the noses of six human volunteers and two adult reindeer. Their findings: Ultra-thin capillaries in the reindeer noses were indeed full of red blood-cell rich capillaries, with a vascular density 25 percent higher than that of humans. According to the researchers, Rudolph's nose blood pathways are merely extra active and extra thick, and they also help regulate the temperature of his brain and keep his nose from freezing (such as during high altitude flying sleigh rides).

There's a little-known Rudolph big-screen movie

Following a hit storybook, holiday standard, and stop-motion TV special that's aired every season for more than 50 years, the next major entry in the Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer media empire was a traditionally animated feature film. Released in 1998, and despite the name and content recognition and goodwill that comes with Rudolph, "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer: The Movie," was a disaster, commercially and critically. Hitting just 102 movie screens in North America, according to The Numbers, Rudolph earned just over $113,000 at the box office, pulled out of most multiplexes after slightly more than a week. Even with a voice cast that included Bob Newhart, Whoopi Goldberg, Debbie Reynolds, and John Goodman (as Santa), audiences weren't interested, and critics were unmoved; for example, Alex Sandell of Juicy Cerebellum called the movie "torturous."

Perhaps filmgoers were turned off by the fact that "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer: The Movie" dared rewrite the story of its titular character, entrenched in the culture from a book, song, and TV special. The film's story (from novice screenwriter Michael Aschner) involves heretofore unmentioned Sprites of the Northern Lights and a vengeful Ice Queen named Stormella who, angry at the accidental destruction of ice statues by a couple of Santa's elves, creates a Christmas-cancelling blizzard (which Rudolph helps the sleigh navigate).

Rudolph has a lot of reindeer relatives

The origin story of "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer" is that it was a department store promotion. The origin story of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, the character, in the mythological Christmas universe of Santa Claus and his North Pole based magical gift-making operation, isn't so straightforward. In Robert May's original story, Rudolph's parentage isn't stated or even implied, nor does the popular Christmas carol give many clues to how the red-nosed reindeer came to be. In the 1964 animated TV special, writers had the space and inclination to flesh out Rudolph's backstory, and a few lines of dialogue imply that the most famous reindeer of all is the son of Donner, traditionally one of Santa's original eight reindeer. However, in the 1998 animated "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer" feature film, another one of the major eight is Rudolph's father: Blitzen.

Meanwhile, according to other, non-canonical entertainments not related to the original "Rudolph" franchise, the titular reindeer has a bigger family tree. According to Joe Diffie's 1995 song of the same name, Rudolph is related to Leroy the Redneck Reindeer. Rudolph has a brother named Rusty in the 2006 TV special "Holidaze: The Christmas That Almost Didn't Happen" (pictured), and in the "Over the Hedge" comic strip, he's got a troubled, jealous older brother named Ralph the Infrared-Nosed Reindeer whose nose can do little more than cook toast.

There are book sequels to Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer

Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (fictionally) saved Christmas and subsequently became a (real) media touchstone, but before he was the subject of a song, TV special, or movie, he was a literary character, appearing in a 1939 giveaway storybook for Montgomery Ward. Writer Robert L. May, after securing the rights to his creation in the mid-1940s (per NPR) returned to Rudolph's literary roots, publishing a not widely known sequel in 1954 called "Rudolph Shines Again." The plot, according to Publishers Weekly (via Barnes and Noble), finds little changed among the reindeer community at the North Pole. Despite safely guiding Santa's sleigh through a foggy Christmas Eve and all the reindeer declaring him a hero, Rudolph has once more been relegated to the bottom of the social chain, assigned menial tasks and excluded from anything fun by all the other, and mean, reindeer. Rudolph runs away from the North Pole and rescues a couple of lost bunnies before once again lighting Santa's Christmas journey.

May actually wrote a different sequel to "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer" before "Rudolph Shines Again." According to WBBZ, May penned "Rudolph's Second Christmas" back in 1947, but it wasn't published until 1991, 15 years after the death of its author.