The History Of The Maccabees Explained

The Jewish holiday of Hanukkah is a minor one when compared to high holidays like Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, but it has gained significant prominence in mainstream culture thanks to its proximity to Christmas, arguably the most dominant holiday in the culturally Christian European-American year. But while many non-Jews might be familiar with some of the superficial aspects of the celebration of Hanukkah such as the nine-branched menorah, eating latkes and other fried foods, and spinning the dreidel, the reason for this 8-day celebration may not be as well-known.

Part of the reason for that is that the origin of Hanukkah lies within the military successes of the Maccabees, a family of revolutionaries whose exploits are recorded in a series of texts called the Books of Maccabees. 1 and 2 Maccabees are considered canon for Catholic and Orthodox churches; 3 Maccabees is only Orthodox; 4 Maccabees only Ethiopian Orthodox; anything else is fully apocryphal. So who were these Maccabees, why do they have so many books written about them, and how was their story so important to inspire a Jewish holiday based on an account that isn't even canon in Jewish scripture?

Judea in the time of the Maccabees

By the time of Alexander the Great's sudden death in 323 BCE, he had conquered most of the known world, with his Hellenistic empire stretching from the Ionian Sea to northern India. However, as the Jewish Virtual Library explains, his death with no legitimate heir led to a succession crisis amongst three of his generals–Seleucus, Ptolemy, and Antigonus–that saw Alexander's empire divided into three. Antigonus claimed control of Greece, while Seleucus took Syria and Asia Minor, and Ptolemy took Egypt and Israel. The placement of Israel in between Egypt and Syria meant that it was smack in the middle of two rival empires for over a century, and the Seleucids and the Ptolemies battled over it for about 125 years.

By 198 BCE, the Seleucids had gained control of Israel and Judea when Seleucid emperor Antiochus III defeated the Ptolemaic Egyptians in battle and annexed Judea into his empire. For some time, Antiochus III left the Jews to relative autonomy, but he eventually decided that the Jews should assimilate to his Greek way of life, and so a campaign of Hellenization was begun. This process of forced assimilation only became worse for the Jews with the accession in 176 BCE of Antiochus IV, who refused to allow any religious exemptions for the Jews as his father had. It is during the reign of Antiochus IV that the Maccabees rose to prominence.

Desecration of the temple

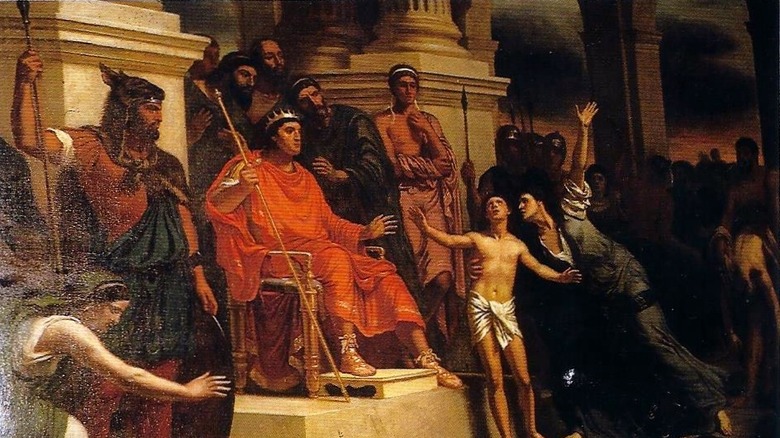

As My Jewish Learning explains, the Seleucid emperor Antiochus IV had the official epithet of Epiphanes ("God manifest"), but he was unofficially known by his subjects as Epimanes ("the madman"). For him, the complete Hellenization of the Jews was simply a step to his ultimate goal: the defeat of the Ptolemies and the conquest of Egypt, which he felt was an essential step to resisting the encroaching might of the new major player on the world stage: the Romans. As such, Antiochus took the assimilation of the Jews very seriously. He began by replacing the Jewish high priest with one loyal to him and sympathetic to his assimilationist campaign. A succession of non-legitimate priests continued until one priest robbed the temple of sacred objects, which led to riotous protests in the streets by the Jewish common people.

When Antiochus heard of this rebellion, any last shred of leniency he had shown the Jews was eliminated. He came to Judea himself, killed thousands of people, and eventually straight up outlawed Judaism. The sacred practices of circumcision, studying the Torah, and keeping kosher were now expressly forbidden. Worst of all, however, Antiochus desecrated the holy Jewish temple in Jerusalem by placing a statue of Zeus on the altar and sacrificing a pig–the prototypical unclean animal–there before despoiling it of all its sacred vessels, gold and silver, and the seven-branched golden menorah that was the symbol of the temple.

Mattathias' five large sons

It is at this low point in the forced Hellenization of the Jews–according to 1 Maccabees 1:11-15, some Jews even reversed their circumcisions in order to appear more Greek–that a family of heroes rises to the stage. 1 Maccabees chapter 2 introduces Mattathias, a priest from the city of Modein, and his five large adult sons: John Gaddi, Simon Thassi, Eleazar Avaran, Jonathan Apphus, and the most famous of all, who actually should have been listed third but is last for dramatic reasons, Judah Maccabee, also known by the Greek version of his name, Judas Maccabeus. As the Jewish Encyclopedia explains, the family is more rightly known as the Hasmoneans, but they and their descendants are popularly remembered as the Maccabees due to the prominence of Judah as a leading figure. The word "Maccabee" is traditionally understood to mean "hammer," which the Jewish Virtual Library explains refers to the hammer-like blows he dealt their enemies.

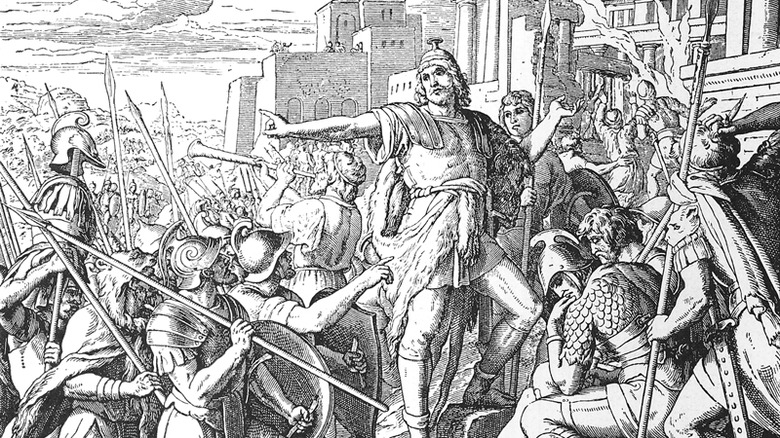

Mattathias sparked a revolt among the Jewish people when he murdered a Greek official rather than be forced to make a sacrifice to a pagan god. Uniting other disgruntled anti-assimilationists, Mattathias and his five sons launched a revolt against Antiochus that began in 167 BCE. According to 1 Maccabees, Mattathias continued as the leader for about a year, at which point he died, seemingly of natural causes, leaving his third son Judah as the commander of the revolt.

The Hammer falls on Antiochus

According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, the early victories of Judah Maccabee were not in open battle, but rather in surprise night raids against villages and border towns in order to destroy the pagan altars and drive out the Seleucids and their sympathizers. Although Judah and his brothers initially had only a small troop of men with them, these successful raids gathered more supporters until they had a large enough force to face the Seleucids in open combat. Initially, Antiochus paid little attention to the Jewish revolt, underestimating their strength of will. Only a local official named Apollonius bothered to even go out to face the Maccabean army; Judah's forces destroyed them and Judah carried Apollonius' sword for the rest of his life.

After this and other victories by the Jewish forces, Antiochus sent more experienced men of war against Judah and his brothers, while he himself went into Persia seeking more money for his battles against his real concern, the Romans. These Seleucid commanders led 40,000 infantry and 7,000 cavalry against the Maccabeans, an army so large that the Greeks had already lined up deals to sell Jewish prisoners as slaves in anticipation of their victory. However, the will and the strategy of the Jews was not to be underestimated, and the Greeks were routed, with Judah alone reportedly killing 9,000 Seleucid men.

The origin of Hanukkah

Judah Maccabee's greatest victory, however, the one at the very heart of the Festival of Hanukkah, came in the autumn of 165 BCE, when he and his forces defeated Antiochus' lieutenant Lysias in a battle south of Jerusalem. According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, despite having lesser numbers, Judah's forces once again used strategy to defeat the more powerful Greek army and force their retreat to the Seleucid capital of Antioch. This cleared the way for Judah's army to make their way to Jerusalem and the temple contained therein.

The account in 1 Maccabees 4:36-61 tells that when Judah and his brothers arrived at the temple, they found the altar profaned, the gates burned, and the sanctuary empty and overgrown with weeds. Tearing his clothes in mourning at the sight of this holy place in ruins, Judah sent men to fight the Greek forces at the citadel of Jerusalem while he and some priests purified the temple. Judah tore down the old altar that had been polluted with unclean blood and built a new one according to ritual law, and he and the priests built new holy vessels and replaced the old lampstand. On the morning of the 25th day of the Jewish month of Kislev, a proper sacrifice was offered at the temple for the first time in years. This is the act that the Festival of Hanukkah commemorates.

But what about the oil?

If you're familiar at all with the holiday of Hanukkah, the account of Judah Maccabee's restoration of the temple might have had you scratching your head and asking, "But what about the miracle of the oil? The eight days and eight crazy nights?" Well, you won't find that account in any of the Books of Maccabees. As My Jewish Learning explains, the story of the miracle of the oil, so central to the modern celebration of Hanukkah with its 9-branched menorah and abundance of oily fried foods, didn't arise until centuries after the institution of the celebration.

What was the reason for the addition of the story of the miraculous oil that burned eight times longer than it should have? There were a few reasons, actually. First, the rabbis felt that it was better that a religious holiday should celebrate a miracle rather than a militaristic and bloody victory. Secondly, following the destruction of the temple by the Romans and the deadly consequences of a later revolt had made the Jewish people wary about bragging about past military victories over the Gentiles. Additionally, a lot of rabbis simply didn't care for the Hasmonean dynasty established by Judah and his brothers. They were seen as usurpers of both the role of the high priest and of king, as the Hasmoneans were not part of either of those hereditary lines.

Antiochus dies of poop disease and worms

After Judah and his brothers had defeated all of Antiochus' generals, 1 Maccabees chapter 5 records victories in neighboring areas by not only Judah, but also his brothers Simon and Jonathan. Chapter 6, however, returns to Antiochus himself, still making a futile attempt to plunder cities in Persia to fund his campaign against the Romans. When the report is brought to him that his general (and guardian of his young son) Lysias had been forced to flee by the Jewish army, Antiochus is shaken to his core. He falls fatally ill from the news of this loss and dies fully believing his death is divine justice for his mistreatment of the Jews.

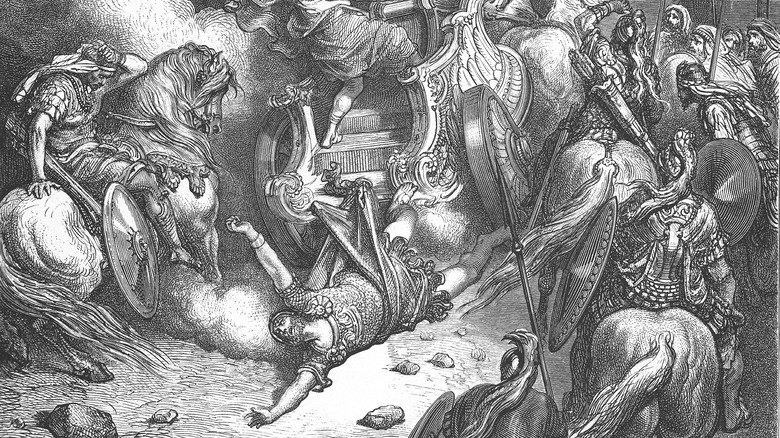

The version of the death of Antiochus recorded in 2 Maccabees is, uh, somewhat different. 2 Maccabees chapter 9 says that the news of Lysias' defeat enraged Antiochus so much that he told his charioteer to drive him to Judea without stopping, swearing "When I get there I will make Jerusalem a cemetery of Jews." At that very moment, God strikes Antiochus with a terrible poop disease that makes him fall out of the chariot and break all of his bones. His body is subsequently plagued with worms, and the smell of his rotting flesh repulses his entire army. God only allows Antiochus to die after he promises that his successor will be kinder to the Jews.

Death of the Hammer

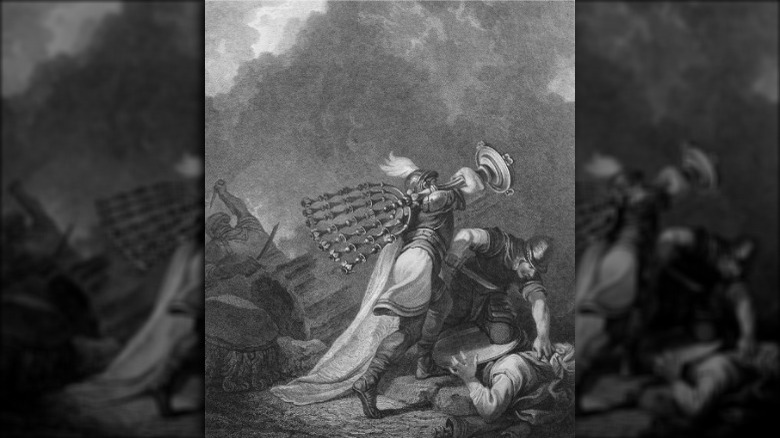

Following the rededication of the temple and the death of Antiochus IV, there was a brief period of peace for the Jewish people. However, as the Jewish Encyclopedia explains, they soon experienced attacks from neighboring tribes who didn't like seeing the increase in Jewish power. Following victory in these battles, Judah next aimed to destroy the Seleucid citadel in Acra. At this point, Antiochus IV's general Lysias and the new nine-year-old king Antiochus V marched a large army complete with war elephants to end Judah's siege. In one battle with this army, Judah's brother Eleazar died in the coolest, most heroic way possible: sliding under a war elephant and slashing it from beneath, being crushed by its gargantuan corpse. Following this, the Jews and the Seleucids reached a peace accord in which the Jews were granted total religious freedom in exchange for living by Seleucid law.

However, certain factions of Hellenized Jews rankled under the leadership of Judah and sought sympathy from the next Seleucid king, Demetrius I. After defeating this renewed wave of hostile forces, including most notably the king's general Nicanor, Judah establishes an alliance with the burgeoning Roman state. Even this was not enough, however, in the face of the next wave of assault from Demetrius, in which the Jewish forces were crushed and Judah himself killed in the thick of battle.

Building a dynasty

As 1 Maccabees chapter 9 records, Judah was succeeded by his younger brother Jonathan Apphus, who took the roles of both military leadership and high priest. According to the Jewish Virtual Library, Jonathan switched up tactics from the way his brother had done things, gaining great success by making clever alliances and bargains with his enemy's enemies. Jonathan managed to increase the glory of Judea and make new alliances with Rome and Sparta, but he was ultimately double-crossed and killed by a treacherous Greek official who feared Jonathan would block his attempt at the Seleucid throne. Jonathan was succeeded as leader by his older brother Simon Thassi, who finally managed to capture the Seleucid citadel in Jerusalem, thereby ridding Judea of the last bits of foreign control (though at the expense of increased Hellenization through foreign alliances with Rome and Sparta), establishing an independent Judea for the first time in 500 years.

As the Jewish Encyclopedia explains, following the assassination of Simon by his son-in-law, his third son, John Hyrcanus, became the first in a line of priest-kings ruling an independent Judea in what would come to be known as the Hasmonean dynasty. This dynasty would last for just over 100 years before being overtaken by the Herodian dynasty, which ended the independent Judea by making it a client state of the Roman Empire.

The gruesome deaths of the Maccabean martyrs

In various Christian churches, August 1 is a feast day for a group of saints known as the Holy Maccabees, or sometimes the Maccabean martyrs. However, as the Orthodox Church in America explains, these Maccabees aren't Judah, Jonathan, or Simon, but rather a number of Jews who died during Seleucid persecution during the Maccabean era. These martyrs included Eleazar, a 90-year-old scribe and teacher who was tortured to death rather than be forced to eat unclean food, and seven young men and their mother who were students of Eleazar. These brothers died in horrific ways, with each one having his tongue, scalp, hands, and feet cut off before being thrown in a giant frying pan. The mother was forced to watch each of her seven sons die one by one in front of her, which she suffered stoically and without giving in to the demands of the Gentiles. She then dies last of all, though the cause of death is not specified.

This doesn't even get into the guy in 2 Maccabees chapter 14, who, rather than be taken captive by the Seleucids, stabbed himself with his own sword, jumped out of a window, ripped out his own intestines and threw them at his enemies until he died. With the gruesome accounts of these martyrs in 2 Maccabees and 4 Maccabees, it's no wonder "Maccabee" is thought to be the origin of the word "macabre."

The Egyptian Maccabees avoid death by elephant

The book of 1 Maccabees is the most thorough account of the deeds of the sons of Mattathias and the Maccabean revolt against the Seleucid Empire; 2 Maccabees is a more sensationalized account that focuses on a briefer period of time and adds cool stuff like flying ghost armies; 4 Maccabees is a homily rather than a narrative, focusing on the lessons we can learn from the faithfulness of the Maccabean martyrs; 5 Maccabees is a wide survey of events from this period of history. As the Jewish Encyclopedia explains, however, 3 Maccabees is a horse of an entirely different color. For one thing, there aren't even any Maccabees in it.

The narrative of 3 Maccabees takes place in Egypt decades before the Maccabean revolt in Judea. It tells the story of Jews suffering persecution under Ptolemy IV after the Egyptian king is miraculously refused entry into the Jewish temple. Ptolemy subsequently returns to Egypt and tries to have all the Jews there executed. When he first tries to have them all registered, their great numbers cause a paper and ink shortage in Egypt. He then has them all thrown into an arena where they are to be crushed to death by 500 drunken elephants. However, after a series of divine interventions including angels coming down and terrifying the elephants, Ptolemy gives up his anger and honors the Jews instead.

The mysterious Ethiopian Maccabees

One final collection of Maccabean stories are collected in the biblical canon of Ethiopian Jews and Christians. These are the books of 1, 2, and 3 Meqabyan, also known as the Ethiopian Maccabees. Despite the name, however, these three books are not about Judah Maccabee and his brothers, nor are they about the Maccabean martyrs, or even the Alexandrian Jews of 3 Maccabees. Nevertheless, these texts, which until extremely recently were only available in the ancient Ethiopic language of Ge'ez, do tell the stories of various Judean revolts against tyrannical foreign kings in the Maccabean tradition.

The book of 1 Meqabyan tells of a man from the Judean tribe of Benjamin called Meqabis, who, together with his three sons Abya, Seelah, and Pantos, refuses to worship the idols of the cruel king Tseerutsaydan. The Meqabyans elude capture by the cruel king only to give themselves up when he threatens to destroy the city. The brothers are tortured, burned in a fire pit, and go to Heaven. Tseerutsaydan tries to dispose of their bodies, but is miraculously prevented from doing so, and the ghosts of the Meqabyans taunt him about the uselessness of his idols. A second group of brothers–Yihuda, Meqabis, and Mebikyas–are introduced later in the book and lead a revolt against the tyrannical king Akrandis of Midian. The books of 2 Meqabyan and 3 Meqabyan are weirder, but also shorter.