The Weirdest Things That Happened To Presidents' Bodies After They Died

While they might live relatively normal lives when they are younger, once someone becomes the president of the United States, everything changes. These days, they can never live a normal life again, unable even to drive themselves places, and always surrounded by Secret Service members, even after they leave office. While things were a little laxer in the olden days, the early ex-presidents still would have found their lives drastically changed after their time on the world stage.

But for all of the micromanaging of presidents' lives that goes on while they are still living, things can go very differently once they are dead. You'd think the reverence and ceremony that surrounds the head of the executive branch would carry over to their corpse, but sometimes that just isn't the case. Some truly bizarre things have happened to the bodies of presidents after their deaths, some immediately, some not until a century later. The intentions behind these very un-presidential incidents were often good, but the problem is that the remains of a president are more ... desirable than your run of the mill dead person. This means people will keep trying to get their hands on them.

You probably learned plenty about their lives in your high school history classes, but for some reason teachers seem to think the story ends when a president dies. In reality, for some of them, the excitement is only beginning. Here are the weirdest things that happened to presidents' bodies after they died.

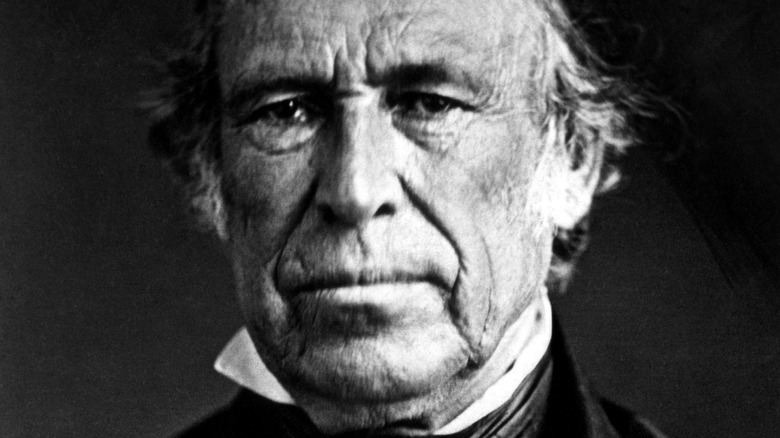

Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor, the 12th president of the United States, is definitely not one of the more famous ones. But his death managed to be so weird that people were still obsessing about it almost a century and half after he died in 1850. Taylor died a little over a year into his first term, at the age of 65. While this was a ripe old age in the mid-19th century, Taylor had been fine only days earlier, even attending a Fourth of July ceremony, according to Politico. Five days later, he was dead. Immediately, some people theorized he'd been poisoned. The motive, so the conspiracy theory goes, was to get Taylor out of the way because he didn't want slavery to become legal in the country's western territories. So pro-slavery people poisoned the milk and cherries he ate at the Independence Day party.

This was such a prominent conspiracy that, just to find out once and for all, in 1991, the body of the former president was exhumed. After lots of scientific tests, it turned out ... no poison. Kentucky's chief medical examiner explained they found evidence of "a myriad of natural diseases which could have produced the symptoms of gastroenteritis."

Anyone who is still desperate to hold on to the conspiracy can use the fact that tests did find some arsenic in Taylor's body, but it was a super low amount, which they determined was "naturally occurring." Who knew people were just walking around with a bit of arsenic in them?

Abraham Lincoln

The assassination of President Abraham Lincoln was a shock. No U.S. president had ever been assassinated before, and it was happening at the very worst time, when the country had only just come to the end of a long and bloody civil war. For a public already reeling, the upheaval and grief must have seemed almost impossible to process. At a time when there was no mass media, the Washington Post reports it was decided that Lincoln's body would go on an extensive journey around the country, thus making "the unreal real for millions."

Lincoln's body was embalmed, something that had only just come to the public's attention due to soldiers being embalmed for shipment home when they died on the Civil War battlefields. But the technology was not yet perfected, and Lincoln's corpse was about to go through a lot: 19 days in an unsealed coffin, traveling on a train, being moved for public viewing in 13 different cities. Even today, that would be asking a lot of an embalmer. Back then, the embalmer had to travel with Lincoln's body and re-embalm it at every stop just to give the chemical façade a chance of working.

Based on the reviews from the time, it didn't. The New York Times wrote about Lincoln's body when the funeral train stopped in that city and predicted, "It will not be possible, despite the effection of the embalming, to continue much longer the exhibition, as the constant shaking of the body aided by the exposure to the air, and the increasing of dust, has already undone much of the ... workmanship."

Abraham Lincoln, Part 2

The strange odyssey of Abraham Lincoln's corpse wasn't over after his very long funeral journey ended and he was finally entombed in a marble sarcophagus in an Illinois cemetery. Turns out, in 1876, some rapscallions thought they would nip in and grab the body, then ransom it off for $200,000. As U.S. News and World Report explains this would be a lot easier than you'd think. There were no guards at the tomb and the sarcophagus itself had just been lightly sealed. The only thing stopping any ole person from entering Lincoln's tomb was one regular padlock. Back then, people were a lot more trusting, apparently, and it wasn't even imaginable that someone would steal Lincoln's body — despite graverobbing and body snatching still being a common occurrence.

Amazingly, even though it should have been ridiculously easy, the gang of Chicago counterfeiters behind the planned crime managed to blow it by asking for help from a guy who was a government informant. When they got to the tomb, Secret Service agents were watching from out of sight. The men filed through the padlock and were attempting to open the heavy cover of the sarcophagus when a gunshot from outside made them scatter.

In order that Lincoln would not risk being corpse-napped by criminals who were better at their job, the president was secretly buried in the tomb's basement. Finally, in 1901, he was disinterred again and buried in a steel cage, 10 feet deep, under tons of concrete.

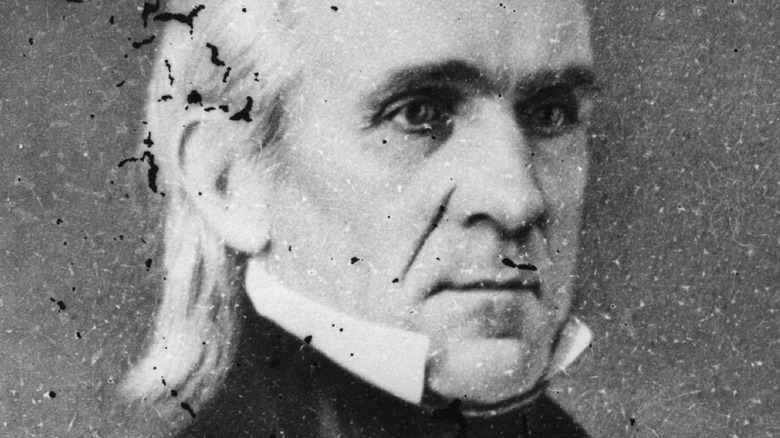

James K. Polk

According to the Washington Post, 11th U.S. president James K. Polk died in 1849, only a few months after his presidential term ended. His cause of death was cholera, which was a very scary disease at that time, and it meant his body had to be buried in a mass grave in order to keep others from getting sick. Obviously, a former president couldn't have that be his final resting place, though. After a year in the common grave in the Nashville City Cemetery, his remains were moved to Polk Place, the estate where he died. But that house and land were sold by the Polk family in 1893, so he needed to be moved again, this time to land occupied by the Tennessee Capitol Building in Nashville.

Surely that must be the end, right? Well, it might be. Or might not. The situation could have changed since you started reading this sentence. That's because in 2017, Tennessee lawmakers started the process of moving Polk yet again, this time an hour away to a home in Columbia that Polk once lived in, NPR explains. The issue is Polk's last will and testament. In it, he said he wanted to be laid to rest at Polk Place, but people have different ideas about why. Was it because the estate was in Nashville, and he loved that city? Or was it because it was his residence, and he'd want to spend eternity at one of his houses, regardless of which one?

In 2018, the final resolution to move Polk a fourth time passed the Tennessee legislature (via AP), but six months later it was put on hold, since they couldn't get permission from the Tennessee Historical Commission.

John F. Kennedy

If you, like thousands of people every year, go visit John F. Kennedy's grave in Arlington National Cemetery, just know that you aren't standing on top of all of him. Yes, the body in the grave is missing a key bit: the brain. Even worse, no one actually knows where it is.

So how did someone lose the brain of one of the United States' most famous and revered presidents? Well, after JFK was assassinated in 1963, his body was autopsied, and the brain was placed in a "a stainless-steel container with a screw-top lid" (via Vanity Fair) which was then "stored in a file cabinet in the office of the Secret Service." From there, it was placed in a "footlocker" and brought to a "secure room" in the National Archives. This must have made sense to someone. But then, according to James Swanson, author of "End of Days: The Assassination of John F. Kennedy," "In October 1966, it was discovered that the brain, the tissue slides and other autopsy materials were missing—and they have never been seen since."

This is obviously a conspiracy theorist's dream, but Swanson's reasoning on why the brain disappeared might shock even them. "My conclusion is that Robert Kennedy did take his brother's brain—not to conceal evidence of a conspiracy but perhaps to conceal evidence of the true extent of President Kennedy's illnesses, or perhaps to conceal evidence of the number of medications that President Kennedy was taking," he said.

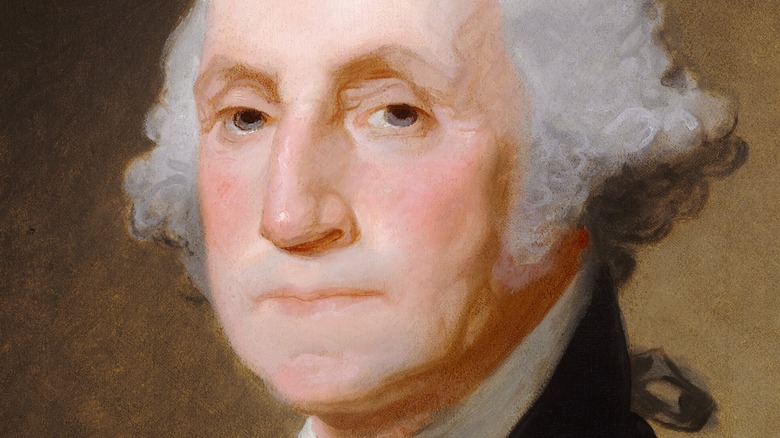

George Washington

Before George Washington died in 1799, he made his will and was quite clear on where and how he wanted to be buried. According to the official website of the first president's plantation Mount Vernon in Virginia, he wanted to stay close to home, but he wasn't happy with the current options. He explained, "The family Vault at Mount Vernon requiring repairs, and being improperly situated besides, I desire that a new one of Brick, and upon a larger Scale, may be built at the foot of what is commonly called the Vineyard Inclosure ... In which my remains, with those of my deceased relatives (now in the old Vault) and such others of my family as may chuse to be entombed there, may be deposited."

That didn't happen at first. Washington's wishes were completely ignored by Congress and his widow, and a crypt was planned under the U.S. Capitol building, but by 1830 that hadn't happened. So Washington's remains were still in the old rundown crypt he'd said needed fixing more than 30 years before.

Then, as explained in "Stealing Lincoln's Body," John Augustine Washington II, who was the childless George Washington's nephew and heir, fired a gardener at Mount Vernon. In retaliation, the gardener decided to steal the late president's skull. But the tomb was in such bad shape that bones of around 20 people were scattered all over and mixed together, meaning the gardener ended up with the skull of one of Washington's distant relatives. After that, a new tomb was erected within a year.

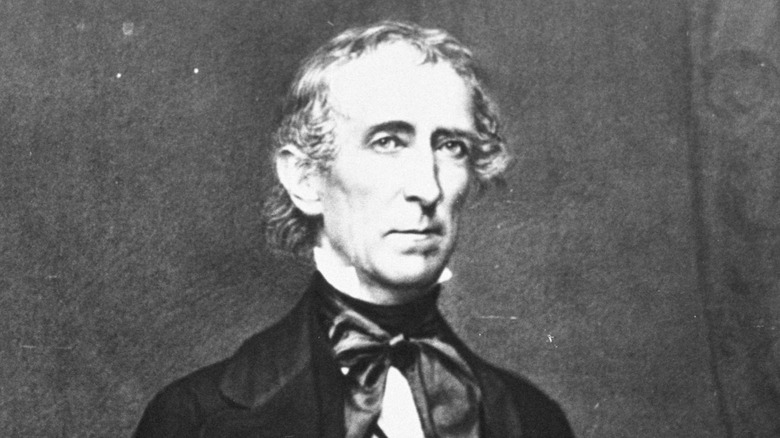

John Tyler

In order to understand how weird John Tyler's post-life situation was, you need to know two things: He was a Southerner, and he died in 1862. This meant that in the middle of the Civil War, the 10th president of the United States was a citizen of the Confederacy. And now the rebels had his body, a potent symbol of statehood. They were not going to miss out on the chance to make a huge deal about it.

In the New York Times' obituary for Tyler, the author did not hold back on how the ex-president was a traitor, and that the Virginian had done "all he could there to take the State out of the Union," reminding readers that after secession Tyler had been elected to the Confederacy's legislature. The scathing obituary continued, "He ended his life suddenly, last Friday, in Richmond — going down to death amid the ruins of his native State. He himself was one of the architects of its ruin; and beneath that melancholy wreck his name will be buried, instead of being inscribed on the Capitol's monumental marble, as a year ago he so much desired."

Tyler was laid to rest in Richmond's Hollywood Cemetery. Their official page explains that despite his expressed wishes for a simple funeral, President Jefferson Davis threw a "grand event" and made quite the statement by draping Tyler's coffin in a Confederate flag. As a result, Tyler's death wound up being "the only one in presidential history to not be officially recognized in Washington D.C."

Warren G. Harding

In 1923, President Warren G. Harding was relaxing with his wife Florence in a San Francisco hotel, when he suddenly dropped dead. He hadn't been feeling too great recently, but then he was on a stressful cross-country speaking tour, and had gotten food poisoning. But he wasn't suddenly-stop-living sick.

Despite the fact that the sitting president of the United States had died for no obvious reason, PBS reports his widow refused an autopsy and insisted her husband be embalmed immediately. The presiding doctors were furious. "We shall never know exactly the immediate cause of President Harding's death since every effort that was made to secure an autopsy met with complete and final refusal," one wrote (via Constitution Daily). The public first blamed the doctors, but in 1930 a former Harding administration official/conman with a grudge wrote a book making an outlandish claim about why Florence made these weird decisions: She'd poisoned her husband, probably because he was constantly cheating on her.

But there's another mystery around Harding that almost led to him being exhumed. According to the New York Times, Harding had an affair with a woman named Nan Britton, which produced a child. But considering there wasn't any way to be sure back then, it was just an allegation. In 2020, that child's child wanted to prove he was Harding's grandson, because even though there was ancestry and DNA evidence, some of Harding's legitimate descendants questioned it. However, once exhumation became a possibility, the holdouts relented, and said there was no need to dig up the late president.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt was a very ill man when he died in 1945, having served three full terms as president and seeing the country through the Great Depression and World War II. But even though he was obviously unwell, his actual death was sudden. According to "Til Death Did Us Part, The Story of the Health and Death of Franklin Delano Roosevelt," the president was at one of his vacation homes with his former mistress when he said he had a "terrific pain in the back of my head" and passed out. He would die three hours later.

Time was of the essence, since embalming works best the sooner it's done to a body. However, in Roosevelt's case, the undertaker wasn't even contacted until four hours after Roosevelt died, then they had to wait until Eleanor Roosevelt showed up since she was next of kin. It had been nine hours when they finally began the embalming process, and as the undertaker F. Haden Snoderly recorded in great detail afterwards, there were lots of issues. In a 15-page memo, he explained that "Rigor mortis had set in," the president's "abdomen was noticeably distended," but worst of all, "the arteries were sclerotic," which made getting the embalming fluid in his veins almost impossible: "[with] the time element ... you can readily understand and realize what a difficult case we had to prepare."

Rumors circulated that Roosevelt hadn't been able to be embalmed at all because he'd been poisoned, and his body turned black. Despite this accusation appearing in a book in 1948, it is not true.

Honorable mention: John Harrison

John Harrison wasn't a U.S. president, but he was the ultimate U.S. president-adjacent person. John, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, was the son of William Henry Harrison and the father of Benjamin Harrison. And unfortunately for the then-future-president Benjamin, something weird happened to his father's body after he died.

John was 73 when he died in 1878, three years before Benjamin was elected, according to the Indy Star. Cincinnati Magazine reports that the Harrison family had learned about a grave in the cemetery that had been robbed recently, and the body of a man named Augustus Devin was stolen. To be sure that wouldn't happen to John, they buried him with extraordinary precautions, topped off with a guard watching over the grave for a full month. After the funeral, Benjamin and his brother decided to help out the Devins and search local medical schools for Augustus' body. But they'd get more than they bargained for.

At one college, they noticed a rope going down a shaft, and realized a body was on the other end, so they pulled it up. In a New York Times article, Benjamin is alleged to have revealed, "Attached to the rope by a hook was the body of my own father. They had known at the college whose the body was. They had taken this fiendishly ingenious method of moving it from floor to floor as we in our search had moved from one floor to another." Somehow, John Harrison had been removed from his grave, and Benjamin Harrison was the one to find him.