How The Nazi Ideology Ruined And Reshaped Christmas

If there's any nation in the world that's most in love with Christmas, it's Germany. So many of the Western world's Christmas traditions come from Germany, it's pretty mind-blowing. It's where the idea of the Christmas tree started, and according to The German Way and More, they were also the ones who started making the first ornaments. That was way back in the 16th century, when glassblowers created stunning decorations that today's mass-produced ornaments can't hold a candle to.

Those open-air Christmas markets that are so much fun, especially with a steaming cup of mulled wine spiked with brandy or rum? Yep: German. The Guardian says the first Christkindlmarkt was held in 1384. Oh, and that drink? The Romans may have first made mulled wine, but it was the Germans who made it Gluhwein and hailed it for supposedly curative powers (via The Kitchn). So, it's safe to say that Germany loves Christmas.

Well, most of Germany.

It was the Nazis who had a major problem with Christmas, and it's easy to see why they wouldn't be down with the entire country spending a month celebrating the birthday of a Jewish man. But Christmas was such a part of the nation's cultural landscape that banning it altogether just wasn't going to work. What's a Fuhrer to do? Co-opt it, give it an overhaul, and try to make it into something completely different.

Why Hitler hated Christmas

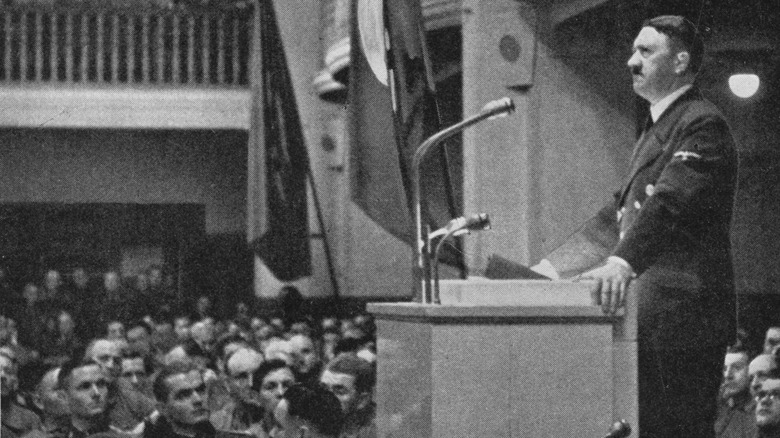

Joe Perry is a Georgia State University history professor, and he says (via The Conversation) that Adolf Hitler started hating on Christmas really, really early on in his career, and some of his early statements are sort of surprising.

It was around Christmastime of 1921 that he gave a speech in Munich, and it was very foreshadow-y, to say the least. While overlooking a major part of Jesus's story (remember, he was not only Jewish, but the scholar Jaroslav Pelikan points out — via PBS — that in several places in the scriptures he's given the title of "Rabbi"), Hitler made it very clear that Jews were the villains of Christmas. He shouted about "the cowardly Jews for breaking the world-liberator on the cross," and he kind of set the stage for his plans about the Holocaust. It was in regard to Christmas that he promised "not to rest until the Jews ... lay shattered on the ground," and this was more than a decade before he was installed in a position of real power.

But there was more to it. Hitler, says Fast Company, also hated the idea that Christmas promoted peace — and it extended to everyone. That's pretty much the exact opposite of what Hitler had in mind for the future of Germany, so there was only one thing left to do: Remodel Christmas.

Nazis set themselves up as defenders of the holiday

One of the biggest questions that comes with the Nazis is, "How the heck did any of this happen?" That goes for their overhaul of Christmas, too, so it's worth mentioning just how they set themselves up in a position to co-opt the nation's most beloved holiday.

Gerry Bowler is the author of "Christmas in the Crosshairs," and says (via the Oxford University Press) that there was a lot going on in Germany in the beginning of the 20th century. Christmas had become something to fight over. While the Communist Party condemned it for being the embodiment of both capitalism and religion, the Social Democrats had their own issues with it. They hated it because it put a very twinkly spotlight on the hypocrisy of well-to-do people who preached charity and good will, at the same time the poor struggled to put food on the table. It got so bad that there were calls to cancel Christmas all together, and that's where Hitler's National Socialists stepped in. "Oh, no, no!" they said. (We imagine.) "You can't cancel Christmas, and we're here to make sure that doesn't happen!"

Hitler's Sturmabteilung — the brownshirts — even took to the street to rough up anyone who was suggesting Christmas needed to be canceled. That escalated to the foundation of a welfare campaign that came around every Christmas, and by the time the Nazis really got to work, they were Christmas champions in the minds of many.

Julfest and Rauhnacht, the Rough Night

Imgard Hunt grew up in Obersalzberg, and she lived under the shadow of Hitler's alpine retreat. Her memoir, "On Hitler's Mountain," recounted what it was like to grow up in Nazi Germany, and one of the things she wrote about (via The New York Times) was how they tried to change Christmas.

At the heart of the co-opting was an attempt to de-Christianize Christmas and return it to the old ways. They wanted Christmas to return to something like it would have been in the pre-Christian, pagan era, and that means renaming it. The entire season became known as Julfest — or Yuletide — and folded into that was a celebration called Rauhnacht. That translates to the "Rough Night," and it was a callback to an era that predated things like running water and gas heaters. People needed to be tough to survive the winters, and the traditions of Rauhnacht gave the holiday season a little bit of that hard edge back.

To be clear, Rauhnacht wasn't a Nazi invention, they just really liked to promote it. Invest in Bavaria says it goes back to at least the 1720s, and it's typically observed between the winter solstice and Epiphany (January 6). That's when people performed ritual cleansings to rid their home of the evil spirits that were thought to roam the earth during these long nights, while others would don homemade — and horrible — masks to parade through the streets and send those spirits on their way.

Christmas got a complete re-branding as an old pagan holiday

Every Christmas, there's a debate: Is saying "Xmas" taking Christ out of Christmas? (No, says Vox: That "X" is sort of a shorthand for Jesus.) The Nazis, on the other hand, really did try to remove any and all mentions of Christ from the holiday. That, says DW, started with the rebranding of the holiday as Julfest, but it definitely didn't end there. Instead of being all about the birth of Christ, Georgia State University history professor Joe Perry says (via The Conversation) that the Nazis tried turning the holiday into something that celebrated the origin story of the Aryan race instead.

It became a sort of neo-pagan celebration of the winter solstice and the return of the sun. They explained the overhaul by insisting that this was the way their people had done things when they were still "racially acceptable," and before they were corrupted by modern religions. Gone was the idea of God and a divine being, and it was replaced with olde-timey rituals that focused more on lights, candles, and calling the sun back.

Not only was Christianity removed, but the Nazis also took the opportunity to turn the holiday into some antisemitic propaganda, too. Jewish businesses were boycotted, shops and catalogs boasted they were Aryan-owned, and the resulting message was very clear: Julfest was Aryan-only, and it celebrated Aryan roots.

Family was at the center of a Nazi Christmas

Christmas is all about family, and for the Nazis, that was both true and different. The Nazis were all about families ... as long as they were the right kind. According to The Guardian, families were also encouraged to celebrate Julfest together, and were sent gifts — like Julfest candles — to be used in the observance of the new, Nazi-fied holiday.

Georgia State University history professor Joe Perry says (via The Conversation) that images released to promote the new holiday had a few purposes. Not only was German media flooded with illustrations of blond-haired and blue-eyed families celebrating Julfest in the "proper" way in order to get families on board with that but adds that it was also used to further ideas about what the perfect family was. Women in particular were targeted, lauded as "protector of house and hearth," and told that it was up to them to make sure their homes were properly Germanic.

In order to really get their point across, they co-opted something else, too. According to DW, Nativity scenes were changed from the traditional depiction of Mary and Joseph looking down at the little baby Jesus, and turned into blond-haired, blue-eyed parents and their blond-haired, blue-eyed baby, to better represent the Nazi ideal. The Nativity stayed, but it looked very, very different.

Writing and rewriting Christmas carols to Nazi standards

Christmas isn't Christmas without the carols, and the Nazis had their hands in co-opting these, too. According to The Telegraph, it was Heinrich Himmler who was put in charge of rewriting carols into something more appropriate. That meant taking religious references out of all of them, and they did. "Unto Us a Time Has Come," for example, was rewritten to remove mentions of Christ, and here's the really shocking thing: The religion-free, Nazi version is the one that stuck, and it's still sung today.

DW says that in other cases, entirely new carols were written — like "High Night of Bright Stars." And yes, the Nazis went a few steps further, because of course they did: Barbara Kirschbaum of the National Socialism Documentation Center says: "The Nazis tried to ban some of the Christmas carols with open Christian content."

And finally, in a "if you can't beat 'em, join 'em" kind of way, Fast Company says that whenever the Savior was mentioned in a carol, the Nazis insisted that be replaced with "Savior Fuhrer."

Santa had to go

Santa is such a popular figure in Germany that there are a couple gift-giving old men that pop 'round during the holiday season. The one that's associated with the Santa Claus of other countries is called Weihnachtsmann, and then there's also St. Nikolaus, who shows up on December 6 and fills shoes with toys and coins. Similar, says The Local, but completely different people.

The Nazis found that Santa was so popular that while they could get rid of Christ, they had no chance of getting rid of the gift-giving figure of Father Christmas. What's a Nazi to do? The answer, says Spiegel, was to claim that it wasn't the Christian saint Nicholas of Myra who was dropping toys into shoes, it was the Norse god Odin.

Fast Company adds that the Nazis kind of doubled down on this one, too. They claimed that this was nothing new and it had always been Odin: Christianity had taken the ancient figure of Odin and assigned him the name and origin story of St. Nikolaus. The Nazis, it went, were just restoring things to the proper and original ways. Once again, they could market themselves as the defenders of the true holiday.

Stars were banned and replaced ... for obvious reasons

Stars have been an important part of Christmas decorations for a long, long time — the Star of Bethlehem appeared in the sky when Christ was born, after all. But according to Spiegel, that's not why the Nazis felt the need to get rid of them. The star meant something else to the Nazis: With six points, it was the star of David used to identify the Jews, and with five points, it was the one won by the Soviet Army.

Fast Company says that the Nazis had a whole list of acceptable symbols to replace the star. When it came time to put something on the very top of the tree, they suggested a swastika — which were, incidentally, also popular for ornaments, allowing for a whole Nazi-themed tree. Other suggestions were the German sun wheel, which the Anti-Defamation League says was co-opted by the Nazis from Old Norse and Celtic mythology, and the lightning bolts of the SS. Those were plucked from a pre-Roman alphabet, and while they're now associated with things like white supremacy and, of course, the Nazis, they were at one time called the sun rune, or sowilo.

Meanwhile, other decorations got replaced, too. Traditional cookie cutters were swapped for swastikas and sun wheels, while ornaments in the shape of grenades, guns, eagles, Iron Crosses, and even little Hitler figures were hung from trees.

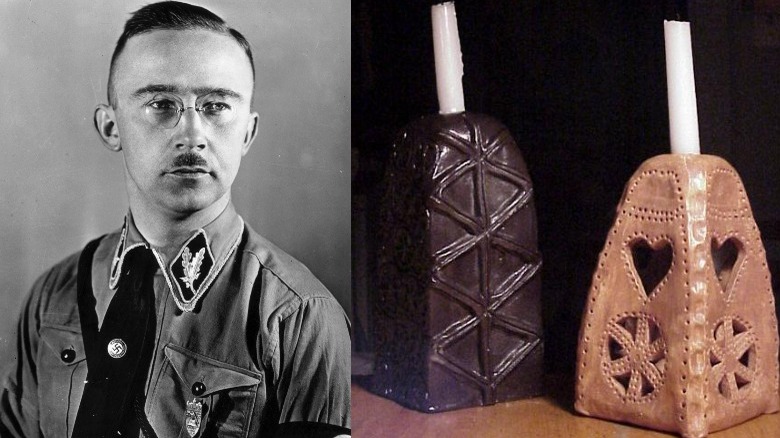

Heinrich Himmler and the Yule Lantern

Just because the Nazis tried to remove both Christianity and Judaism from Christmas, that doesn't mean it was religion-free. Anyone looking for unusual Christmas decorations to add to their holiday celebrations today can still buy the lantern called the Julleuchter, or Yule lantern. They're essentially a kind of lantern or candlestick, and while their distinct design was inspired by earlier Nordic lanterns, NS Kunst says that the concept was purely the invention of Heinrich Himmler.

The purpose of the Julleuchter was described in Fritz Weitzel's book "The Celebrations In The Life Of The SS Family." According to the text, it was to be displayed prominently in an "SS-corner" of the home, which would include "all those things ... which strengthen the voice of our blood and the duties to land and Folk, everything that demonstrates our beliefs." While other things around the Julleuchter would change based on the season, the lantern would always be there.

Himmler wanted every member of the SS to have a Julleuchter specially gifted from him, and there were a lot made — by, says Spiegel, the prisoners at Dachau and Neuengamme. It's unclear how many were produced and how many were used by their intended recipients, but they still have managed to hold on as a lasting reminder of the Nazi influence on the Christmas holiday.

How successful was it?

Here's the million-Reichsmark question: Did people buy into this new Nazi Christmas? Georgia State University history professor Joe Perry says (via The Conversation) that it's hard to tell, but there are some documents that give us an idea of what the reaction was like, particularly among the women who were dubbed "priestesses" of this new holiday.

The National Socialist Women's League (NSF) was, says UNC-Chapel Hill, the women's corner of the Nazi Party. There were more than 2.3 million members as of 1933, and they brought some major pushback against the remodeled Christmas. Records speak of "much doubt and discontent" within the organization, while churches went very public with their condemnation of the Reich's new winter holiday. Scores of women cited Julfest as their reason for not joining the NSF, and it probably didn't hurt that in some places, their churches had made it quite clear that they would be excommunicated for joining.

That said, reports compiled by the Nazi's secret police reported on how popular Julfest was. These were the families that wanted traditional celebrations reserved for the Aryan families, but still, there were plenty that still put that star on the top of their trees.

Christmas and Julfest as the war dragged on

By 1944, pretty much everyone was sick of the war — and Nazi propaganda around the winter holiday actually reflected that. While much of the correspondence from early in the war involved things like how to make Nazi-fied cookies, Spiegel says that as the war dragged on into 1945, the Nazi powers-that-be tried to reinvent the holiday again, and make it a commemoration for the soldiers who had died protecting the homeland. Every year, holiday propaganda circulated — and that year, Traces of War says it included stories like the tale of a German man who only wanted to return to Germany to die.

A speech written by Thilo Scheller was published in "Die Neue Gemeinschaft," or "The New Society." It was supposed to be read out in military hospitals where German soldiers lay injured and dying, and reminded them that "our Fuhrer Adolf Hitler ... will not forget those who cannot celebrate Christmas with their loved ones." Every celebration, they wrote, should include "all our dead comrades from all the battlefields of Europe."

Now, the holiday turned into a "cult of death," with illustrations of decorated trees over graves marked by Iron Crosses. Official recommendations for celebrations included lighting candles for "the mother, the poor, the dead, and the Fuhrer," setting a place at the dinner table for the dead men of the family, and lighting red candles in their memories.

Christmas in the camps was brutal beyond belief

The Nazi party didn't just have their official guidelines for how Christmas was going to be celebrated under the regime, the SS guards in charge of the concentration camps had their own ideas, too — and it was brutal. Auschwitz-Birkenau, for example, had a Christmas tree. It was set up in the area where roll call was taken every day, and that Christmas in 1940 was the Christmas when prisoners were greeted with a grisly sight: Piled beneath the tree in lieu of brightly wrapped packages were the corpses of the recently dead. The Memorial and Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau has collected testimonies of camp survivors, and it was Karol Swietorzecki who recalled the guards referring to the bodies as "a present."

On Christmas Eve in 1941, around 300 Soviet POWs were killed in a holiday sacrifice, and that same year, prisoners were forced to stand outside in the freezing temperatures as they listened to Pop Pius XII's Christmas speech. Dozens died where they fell.

The grisly Christmas tree was back in 1942, and in 1943, they were allowed actual gifts from their families. By 1944, it wasn't about what the Nazis wanted anymore, not entirely. Primo Levi was a prisoner there for that Christmas, and later wrote (via Tablet), "At night, when all the noises of the Camp had died down, we heard the thunder of the artillery coming closer and closer."

Liberation came just after New Year's, on January 18.