What Christmas During World War II Was Really Like

It's one of the most fundamental — and sometimes cruel — of all truths: It doesn't matter what's going on in your life, what you're feeling, or what you're dealing with, time will still keep ticking away. Days will keep passing whether you want them to or not, and if things like birthdays or Christmas seem like too much to deal with right now, well that's just too bad.

There's perhaps no time that's more evident on a large scale than during World War II. Nothing was right in the world — men and women on the front lines didn't know if the next breath would be their last, families on the home front wondered if their loved ones had died since they got that last letter months ago, and children just didn't know where their family had gone. It was an unspeakable time, and it's safe to say that even during Christmas, people may not have felt much life celebrating.

Still, stiff upper lip and all that. During the war years, families at home and away all found ways to at least recognize the holiday — and remember those that were so very far away, along with those that were gone forever. And others? Well, they just tried their very best to survive, in hopes that the next Christmas might be better.

Christmas 1944: One of the war's bloodiest battles

The Christmas of 1944 was as far from the Christmas spirit as anything can get: According to The Washington Post, the death toll of the fighting around the town of Bastogne, Belgium was staggering, with 19,000 dead, 23,000 taken prisoner, and nearly 50,000 wounded. There's really no better way to talk about the Battle of the Bulge than from the point of view of those who were there, like John Prior. A doctor with the U.S. Army, he spent that Christmas Eve sifting through the bombed remains of the apartment building that he'd been using as a hospital. Among the dead was his nurse, Renee Lemaire. He'd later recall that he had returned her body to her father, wrapped in parachute silk that he'd saved for her. She had hoped to make a wedding dress from it.

The entire saga is riddled with horrible snapshots into some of the most brutal fighting of the war. Around 100 women and children were executed by the German advance outside Stavelot. At Malmedy, 84 American prisoners were executed, and just days later, Germans surrendering to another group of Americans were massacred in retribution. The suburb of Noville became "a shooting gallery." It all happened as temperatures dropped to below freezing, and men froze and died where they fell.

Inside, soldiers still standing had dinner: A hamburger patty and a handful of mashed potatoes, eaten with bare, dirty hands. And then, on Christmas Day, the real fighting began.

Christmas dinner and rationing

What families were able to serve for Christmas dinner changed as the years went on and rationing got stricter. War History Online says that 1940 was the first year that Christmas dinner was hit by rationing in the European Allied countries, and by 1941, even basics like cheese, milk, and eggs were scarce.

In the UK, the government published pamphlets to give families ideas for homemade gifts and Christmas meals. Some of the suggestions from the Ministry of Food (via the BBC) included serving things like carrot soup, carrot fudge, and candied carrots, carrot cake with cream, and boiled carrots. They also suggested things like parsley and celery stuffing, but it's safe to say that Christmas dinner in Britain was very carroty. As far as meat goes, rabbit was a suggested substitute for the traditional Christmas bird, and according to Historia, another common replacement was ox heart and offal.

People at home went without so those on the front lines could have hearty meals, and according to genealogist and historian Gena Philibert-Ortega, they did. She found (via Genealogy Bank) that many Allied soldiers were able to enjoy roast turkey dinners with stuffing, cranberry, and all the fixin's. In 1943, Captain George Nabb Jr. wrote to his family (via The National WWII Museum): "We all drank a toast just before dinner to our next Xmas in the U.S.A. I hope and pray we shall be there." They were not.

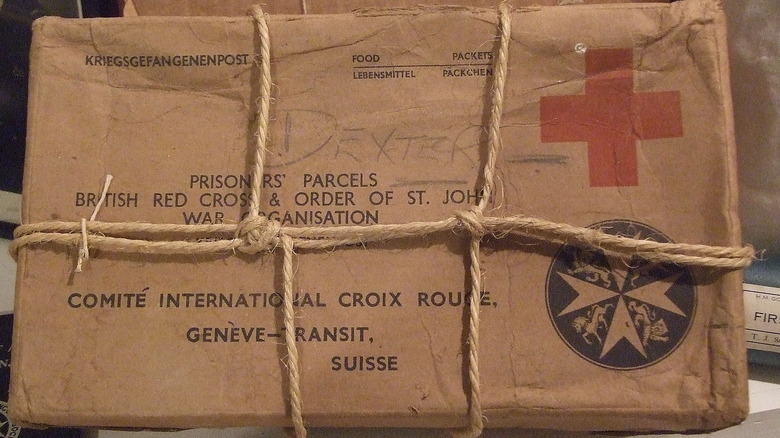

POWs looked forward to Red Cross packages

According to the WWII U.S. Medical Research Centre, the almost 1.4 million Allied POWs received over 27 million Red Cross relief packages during the course of the war. Most of the everyday packages contained things like canned fish and corned beef, soap, coffee, pate, and other non-perishable food items, along with hygiene items and clothing.

In 1944, they organized around 75,000 Christmas packages that were shipped to Allied POWs held in German camps. The National WWII Museum says they were packed and shipped during the summer to make sure they got there in time for the holidays, sent via Swedish ships and then transported into the heart of Germany.

Getting these packages must have been like a very real visit from Santa. They included things like butter, honey, candy and gum, turkey, sausages, and ham, pipes and cigarettes — along with tobacco — and playing cards. For those POWs being held in Stalag Luft III — who celebrated with a massive party — it was a bright light before what would be a very dark January: Less than a month after Christmas, the camp was evacuated. Thousands of men were forced to march through the snows of one of the coldest winters in living memory, and many would die.

Christmas in the camps: The horrors of a Christmas tree

Think of WWII, and it's the concentration camps that come to mind first. Christmas came and went there, too, and according to the Memorial and Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau, accounts of those who survived the camp's horrors describe holidays both horrifying and inspiring. The first Christmas for Auschwitz-Birkenau prisoners came in 1940, and the thing about the concentration camps is that they're more horrible than any work of fiction anyone has come up with. Ever.

The SS absolutely had their own Christmas tree in the middle of the camp, fully decorated and underneath it, they piled the corpses of prisoners who had died during the morning's roll call. Survivors recalled that it was the work of Lagerfuhrer Karl Fritzsch; it's a name that isn't widely known, but important: He was, AD says, the man who was disliked by his fellow Nazis but got some street cred for coming up with the idea to use Zyklon B for mass executions. He was there for that first Christmas, and told everyone that the corpses under the tree were their gifts.

The grisly Christmas tree was back on display in subsequent years: In 1942, men from the labor camps were chosen and told to gather dirt. Those who came back with the smallest piles of dirt were killed and put beneath the tree.

Christmas in the camps: Getting through the day

While Nazi guards took the chance to create grisly, horrible scenes of atrocities, the Memorial and Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau says prisoners retreated to their cell blocks to do something else: comfort each other. Jozef Jedrych was in Block 10a, and later wrote that even as the Germans sang their carols, Polish prisoners began to sing theirs, too. "Everyone exchanged warm, cordial embraces and cried for a long time. There were those who sobbed out loud ... Such a grand moment never fades from memory. That Christmas is fixed forever in my heart and memory."

Some prisoners smuggled in little Christmas trees of their own, decorating them with carvings created in secret. They gathered together, sang carols, and some even lit candles that they, too, had smuggled into the camps. By Christmas of 1944, Nazi commandants who knew the end was nigh lifted some restrictions. Midnight mass was celebrated, and some of the women in Birkenau were allowed to sew gifts for the children.

Liberation would come weeks later.

The real-life Father Christmas who organized holidays for POWs and children

In 1942, The Atlantic ran an article written by a pretty incredible person. His name was Josiah P. Marvel, and as a Quaker, wasn't permitted to serve in a combat role, but he was a member of the Quaker Emergency Service. When The New York Times reported on his death in 1959, they noted that he was the only Allied social worker that had express permission from the Gestapo to enter prisons in occupied France, and care for the people there. And that included organizing Christmas parties.

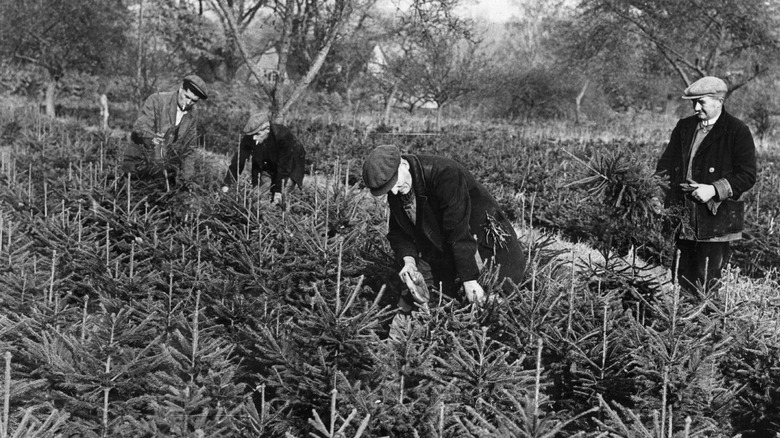

His description of what went into the parties is wild, and it started with borrowing German trucks to head out and collect Christmas trees, which were then set up on each prison floor. German officers helped him compile a list of the prisoners who had never received any packages from the outside, and Marvel bought them extra gifts — like clothing and toiletries — in addition to the apples and oranges that he purchased for hundreds of prisoners. He traded some of his own rations to get a baker supplies to make a cake, along with a fruitcake for each of the British prisoners.

He organized meals, set up trays of desserts and chocolates, and listened — and cried — as prisoners and guards alike sang carols together. It was bittersweet, and he wrote, "'Peace on earth, good will to men' — the words we had sung seemed hollow. ... I wondered if it could, if it would, ever come about."

During the Blitz

Christmas of 1940 brought with it devastation from above for the city of Manchester: According to the BBC, 684 people were killed, 2,300 were injured, 8,000 families lost their homes, and entire sections of the city were turned to rubble on December 22, as Luftwaffe planes dropped waves of bombs. That year, Christmas carols were replaced by air raid sirens, and survivor Susan Jones described it like this: "It was a dreadful thing. I looked up at the sky and it seemed like everything was on fire. There was an acrid smell of burning and from the guns."

In the midst of it all, a German radio broadcast boasted (via the Manchester Evening News): "The Manchester people have bought their turkeys for Christmas, but they won't be cooking them."

Things weren't much better to the south. Fear of bombing raids led to city-wide blackouts, meaning that Christmas lights and decorations were absolutely forbidden, says the BBC. The Imperial War Museums says that by Christmas of 1940, London had been subjected to 57 nights of continuous bombing. That meant many headed to the relative safety of underground air raid shelters, and by 1941, underground canteens had been set up to give people a place to go to at least have a hot drink and a bite to eat as they "celebrated" the holiday, and wondered if their homes would be there when they returned to the surface.

Christmas for the kids

It's often said that Christmas is for the kids, and it really is. But Christmas during the war meant that many kids, too, had to change what they thought of the holiday. With London and other major British cities being major targets for German bombing runs, many families made the hard decision to evacuate their children to the countryside. According to the BBC, those parents were told not to let them come back for the holiday — it was going to make the separation that much harder, and many just weren't going to want to leave again.

Presents were hard to find, and many children received gifts related to the war. That might be a miniature military uniform, card games, or books explaining what was going on in the very weird world they were living in. Historia adds that many were given homemade gifts that were often practical, and when you're away from home for months on end, suddenly a sweater or toy made by your mom takes on a whole new meaning.

When the U.S. entered the war, they brought a lot of much-needed goodness with them, and sometimes, it came from surprising places. From 1942 onwards, Christmas time in Britain changed for the kids as American troops threw Christmas parties on military bases and shared their rations and care packages with British families.

The Nazis took Christ out of Christmas

Christmas in Nazi Germany looked like no Christmas had before or since, mostly because — perhaps predictably — DW says they completely overhauled a holiday that was celebrating the birth, life, and sacrifice of a Jewish man. It became Julfest instead of Christmas, and it was said to be based around the winter solstice.

Joe Perry, a history professor at Georgia State University, says (via The Conversation) that Nazi officials decided to remake Christmas by rewriting a little bit of history. Based on the idea that the whole thing had grown out of old pagan rituals — the true Germanic tribes that had existed before they were corrupted by Christianity and Judaism — they turned Christmas into "a celebration of pagan German nationalism."

Gone was any mention of Christ, and the long-observed version of Christmas was replaced (officially, at least) with an adoration of the Nordic and the Aryan. Carols were rewritten to be up to Nazi standards, homes were decorated with swastika ornaments and Odin's Sun Wheel, and even Christmas cookies were given a redesign into shapes promoting things like the reproduction of the Aryan race. Oh, and the traditional Nativity scene? That was redesigned to feature blond-haired, blue-eyed figures that represented the "perfect" German family.

The only documented Christmas truce

The Christmas truce of 1914 is perhaps one of the most famous stories to come out of World War I, but according to the American Battle Monuments Commission, the same thing didn't quite happen during the second go-around. If anything, the fighting was even more fierce in 1944, building up to the D-Day landings at Normandy. There was, however, a single documented instance where there was a small-scale truce, and it happened in a little cottage nestled in the forest of Huertgen.

That was where Fritz Vincken and his mother had moved after their home was destroyed, and it was Fritz that recorded the events of that very same Christmas Eve, when his mother answered the door to find three American soldiers there. It wasn't long after they got them settled that there was another knock at the door, but this time, it was four soldiers of the Wehrmacht. Knowing they could be executed on the spot for treason, they had no choice but to allow them in as well. They did — with a quick plea from Fritz's mother, who asked that if for one night, they could just remember that it was Christmas Eve, and coexist in peace.

They did — conversing in French, they found out that the Americans were only 16 years old, and the oldest of the Germans was 23. They ate together, said prayers, looked up at the stars, and finally, slept. The next morning, they shook hands and returned to their opposing sides.

Christmas ornaments were changed forever

For decades, Christmas and Germany went together like egg nog and brandy. Not only did the Germans love a great Christmas, but they shared that love in the form of ornaments. During World War I and II, the most beautiful of hand-made ornaments came from Lauscha, a small mountain town that Homes & Antiques says was the home of hand-blown ornaments. That was fine — most of the time — but during the war, the last thing Allied families wanted was German decorations on their trees.

The National WWII Museum says that many families threw away their German ornaments, and that meant directing some serious creative energy into making new ones. Paper chains were made from newspapers and magazines, says Historia, while toilet paper was used to very, very carefully cut snowflakes for hanging in the windows. Fortunately for those Americans who loved decorating, it was another German — immigrant Max Eckardt — to the rescue. He, says Pennsylvania Wilds, founded Shiny Brite, the first company making mass-produced ornaments. With help from Corning, they made 40 million ornaments in 1940 alone.

Natural decorations, too, were all the rage. Historic UK says that while Christmas lights weren't allowed, families were encouraged to head outside and cut boughs of holly, mistletoe, and other evergreens for decorating inside. They even recommended dipping the greenery in Epsom salts: "When dry, it will be beautifully frosted."

There were tons of difficulties in getting trees

It might seem logical that families on the home front would at least be able to find a little Christmas cheer by getting their own Christmas tree, but trees were actually in short supply. The National D-Day Memorial Foundation says that was for a few reasons. For starters, any places that had their trees grown elsewhere and shipped in were out of luck, because commercial and industrial transportation was being dedicated to the war effort — as were the trees themselves, a valuable source of lumber. There was also a shortage of workers that were ready, willing, and able to head out and cut the trees in the first place, and that all drove prices through the roof. Pre-war, a Christmas tree would set the average family back about 75 cents. Once the U.S. got involved in the war, though, that same tree would sell for around $35 dollars. (That's the equivalent of around $575 in today's money.)

It's no wonder, then, that Christmastime during World War II marked the first year they purchased an artificial — and, more importantly, reusable — Christmas tree.

For soldiers living and fighting abroad, Christmas trees were just as important. Many would cut nearby trees and decorate them with whatever they happened to have handy, and for those in the Pacific, that often meant using palm trees.

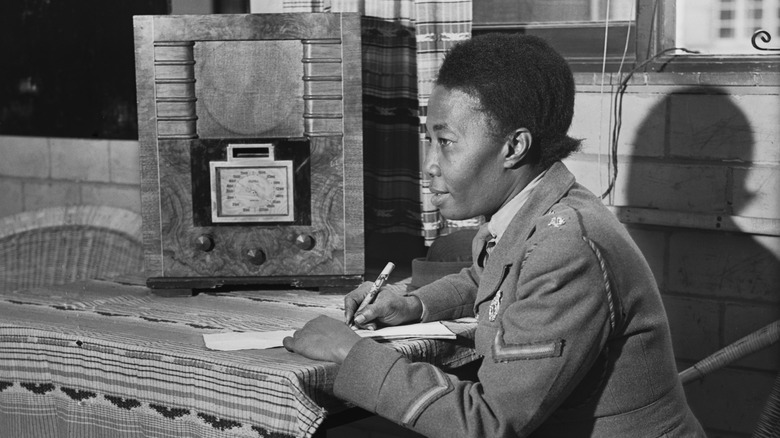

Together across the miles: The Command Performances

The most defining feature of holidays during wartime is the knowledge that loved ones are so very far away — and that's where The Armed Forces Radio Service came in. "Command Performance" was a huge deal to enlisted personnel — it was a variety show that starred some of the biggest names of the day, and according to The National WWII Museum, it remained mostly a military thing until Christmas Eve of 1942.

That's when the Office of War Information, the American Forces Network, and the Armed Forces Radio Services decided to team up with civilian broadcasters, and broadcast the same thing across the airwaves. It would allow servicemen hunkered down across the European and Pacific Theaters to know they were listening to the same thing that their loved ones were listening to on the home front, and that's a lovely idea.

That first edition featured names like Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, the Andrews Sisters, and even comedy by Red Skelton. They were back for other Christmas Eves, and it was such a huge success that other shows were added. Those tuning in on Christmas Eve of 1944 would have heard "The Jack Benny Program," and in 1945, the Christmas broadcast celebrated the end of the war.

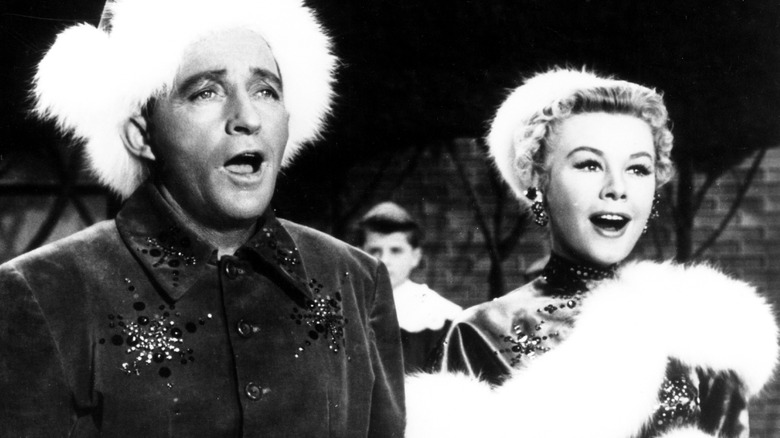

The most popular Christmas carols of the Allied airwaves

It's no secret that with Christmastime comes the same dozen or so songs, played on repeat, 24/7. Many of these songs are pretty modern, so what were people listening to during World War II?

There were two songs that defined Christmas of the war era, and the first was Bing Crosby's "White Christmas." According to The National WWII Museum, the song debuted just after the attack on Pearl Harbor brought war to America's doorstep, and at the time, it wasn't that big of a deal. Americans had other things on their minds, but by the holidays of 1942, it was sitting comfortably at the top of the charts. It's easy to see why: There's nothing about war, but it taps into a feeling that everyone had at the time — a longing for holidays to be like they were before the world went all sideways and upside-down. For millions, there would be no more white Christmases.

Then, 1943 saw the debut of another wildly popular song, one that History Daily says was regularly requested throughout the year. "I'll Be Home For Christmas" was also by Bing Crosby, and it spoke to entire generations. There were soldiers wishing they were home, families desperately wanting to hug their loved ones, and children wondering where their fathers and brothers were. It was so moving, in fact, that it was banned by the BBC for being too depressing. But the truth is, for many, that's what Christmas was: sad.