The Dark Side Of The Silent Film Era

The golden age of silent movies spanned from approximately 1910 to 1927, an era that witnessed seismic upheavals in technology, economics and social values. As movies became cheaper to make and studios streamlined production and distribution, the medium slowly but surely began to replace vaudeville as the number one form of entertainment.

Unlike live shows, movies could reach audiences across the country. Suddenly someone in New York could be watching the same performers as someone in LA. This, coupled with early fan magazines that were heavily directed by the studios, created the very first movie stars. They were simultaneously relatable and glamorous: aspirational figures who nonetheless felt like friends.

However, behind the stage scenery, pancake makeup and early special effects were stories of drug and alcohol addictions, sexual harassment, and stars behaving in not very starry ways. These blemishes on Hollywood's close-up were covered up using studio clout. But some stars would discover that clout worked both ways. Hollywood ran on open secrets: Rumors everyone heard but no one discussed, until it started interfering with the industry's image. Sometimes these stories made it out to the press — including several supposed murders — and even the courts. And sometimes it took decades for observers to look back and understand just how toxic a situation really was. This is the dark side of the silent film era, including the extent of studios' control over their stars and their product, and murder mysteries worthy of the movies.

Hollywood studios controlled their stars' images

In the first decade of the motion picture industry, actors didn't use their own names. Between 1906 and 1909, one of the most popular actresses was known only as The Biograph Girl, after the studio where she got her start. Her real name was Florence Lawrence — as the public found out when the boss of her new studio pulled a publicity stunt to put Lawrence's real name in lights. She became the first movie star, a box office draw in her own right, Vanity Fair reports.

The reluctance around revealing actors' names came down to studio executives' concerns — which were correct, it turned out — that if actors got famous on their own terms, the balance of power would shift in the performers' favor.

These executives sought to control actors not just on set, but in everything they did. Under what came to be known as the "star system," actors signed lengthy contracts with one studio, which then dictated their public persona. One of the most extreme examples of this storytelling/propaganda is the remodeling of actress Theda Bara, real name Theodosia Goodman. In 1915, Bara was cast as a vamp (a sexy Goth) in Fox's movie "A Fool There Was." The studio remade the bookish Cincinnati native in her character's vampy image: Picture metal bikinis and skeletons. Bara's contract with the studio banned her from riding public transport and going out during the day. Celebrities today lose their privacy: Silent movie stars lost their identities.

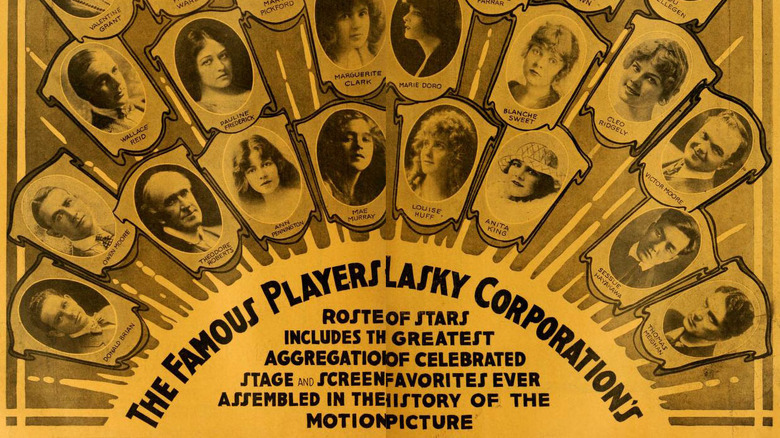

Hollywood studios were charged with operating monopolies

In addition to exerting control over stars, Hollywood studio executives in the silent era and beyond used monopolizing tactics to maximize profits, bully distributors, and shut out competitors. The major studios bought their own movie theater chains. Making their own movies the only show in town ensured ticket sales. Studios also resorted to other methods of controlling distribution, as explained in a 1928 lawsuit filed by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) against the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation (later Paramount) and nine other studios. For example, the practice of block booking forced movie theaters to buy a studio's blockbusters in an expensive package with its duds. According to the Department of Justice (DOJ), the studios also fixed ticket prices, and entered into exclusive deals that prevented certain theater chains from showing movies (known as circuit dealing.)

These practices accelerated throughout the silent era, and only ended in 1948. That year, Variety reports, the Supreme Court ordered the five major studios — MGM, Warner Bros., Paramount, RKO and 20th Century Fox — to sell their theater chains. These big studios and three smaller-but-powerful ones — United Artists, Universal and Columbia —were forced to agree to what became known as the Paramount Decrees, which outlawed practices such as block booking.

However, in 2019, the DOJ under then-President Trump asked a court to end the decrees, given, it said, how much the movie industry has changed in the decades since.

Studio fixers covered up stars' indiscretions

Signing a contract with a studio didn't just get you acting work and a makeover. It was in studios' best interests to protect their stars from falling foul of turn-of-the-century morality police. As the New Yorker reports, if stars found themselves wrapped up in a scandal, the studio would flex its influence to cover it up. The scope of the incidents that got this hush-hush treatment ranged from public drunkenness, illegal abortions and homosexual relationships, to fights, car wrecks, rape and murder.

The Hollywood studios employed "fixers," who did exactly what their job title implies. MGM had two of the most effective and most notorious. Howard Strickling's official job title was Head of Publicity, but he acted more like a spin doctor and sometime briber. Meanwhile, his colleague Eddie Mannix (pictured) could politely be called the muscle. He intimidated not only witnesses who saw too much, but stars who repeatedly crossed the line.

If a star kept causing issues for their studio, they could find themselves on the wrong end of the fixers' skill sets. For example, in 1930, silent movie superstar Clara Bow got involved in a lawsuit against her former secretary, who spilled the beans on Bow's already much gossiped-about sex life. Instead of protecting its star, Paramount spread more rumors, which ultimately gave the studio the excuse it needed to fire the out-of-favor actress.

Homosexuality was repressed

One of the silent era's most lauded stars caused a battle of the sexes. Italian-born Rudolph Valentino was the archetype of the "Latin lover" persona. Female fans saw him as the epitome of the tall, dark and handsome stranger, a romantic hero. But straight men saw Valentino as effeminate, and therefore as gay — scandalous, as far as they were concerned. As Vanity Fair reports, in 1926, a Chicago Tribune editorial "blamed" Valentino for American men becoming "feminized."

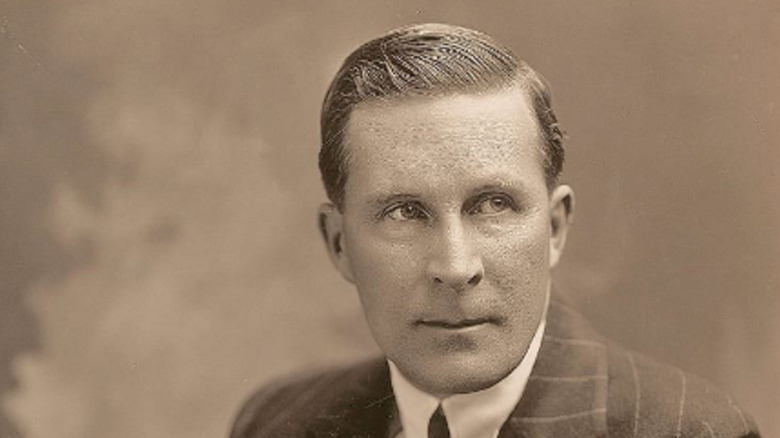

Valentino (whose sexuality is still contested) reacted to these criticisms of his masculinity with denials, and an offer to box the editorial's writer. Being openly gay in the 1920s would likely have ruined his career. However, some movies and stars operated in a grey area. The 1922 movie "Manslaughter" featured a romantic same-sex kiss, and the very first Best Picture Oscar winner, "Wings," featured a soldier kissing his dead comrade on the lips. In the late '20s, it was well known (but not discussed) among everyone in Hollywood that William Haines (pictured), the most famous romantic male lead, lived with his male partner.

There were also a significant number of bisexual and lesbian women, including actors and people behind the scenes. Superstars Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich were far from the only women in Hollywood who had same-sex romances. This not-entirely-secret subculture was based at Russian-born actress Alla Nazimova's Hollywood haven, the Garden of Alla, where she hosted parties known as "sewing circles" for women to meet other women.

People of color were ostracized in Hollywood

The major Hollywood studios in the silent era didn't typically hire non-white actors for leading roles. If a story included a character of color, more often than not, they were played by a white actor in blackface or yellowface. That's the practice of using makeup to present a white actor as a Black person or someone of Asian descent, respectively. These characters were usually little more than stereotypes. For example, when she wasn't being passed over for white actresses, Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong (pictured) was often cast as mysterious and untrustworthy femme fatales.

The success of one silent movie in particular suggests that Hollywood wasn't just ignoring people of color: it was promoting narratives that put them in danger. D.W. Griffith's 1915 movie "Birth of a Nation" was a three-hour-plus piece of Ku Klux Klan propaganda. It immediately became a successful recruiting tool for the domestic terror group. It was also the "Avengers: Endgame" of its day, both in terms of box office success, and in that it created an appetite not so much for a certain genre of movie, but for feature movies generally.

However, Black people both appeared in and made movies away from Hollywood. As the Smithsonian reports, there was a thriving industry staffed mainly by Black cast and crew making so-called "race films," about and for Black people. In 1920, one movie, "Within Our Gates," which repudiated Griffiths' hateful rhetoric, became popular even with white audiences.

Sexual harassment was considered normal

The term "casting couch" became prevalent in headlines during the peak of Hollywood's #MeToo scandal in 2018. It refers to actresses being pressured to do sexual favors for powerful movie executives, in exchange for roles or other career help. By then, the concept was over 100 years old. According to the Atlantic, the term originated in the offices of the Schubert brothers, the trio who made Broadway the heart of America's musical theater scene.

When movies replaced musicals in the publics' hearts, the casting couch moved to Hollywood. As the Guardian reports, actress Louise Brooks, considered one of the ultimate flapper idols, recalled hearing about young aspiring female stars receiving contracts at major studios after such meetings with executives. These manipulative arrangements were something of an open secret.

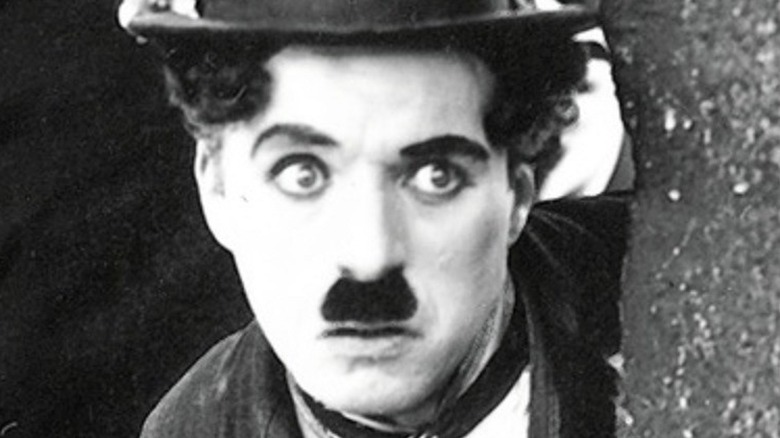

It wasn't just executives abusing starlets. Charlie Chaplin (pictured), arguably the most famous silent movie star to this day, was notorious for dating and marrying teenage girls. He was 29 when he married his first wife, who was 16 at the time; 25 when he married his second wife, who was 16 by then but had been 12 when they met; and 54 when he married his third (maybe fourth) wife, who was 18.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Safety standards were dangerously low on sets

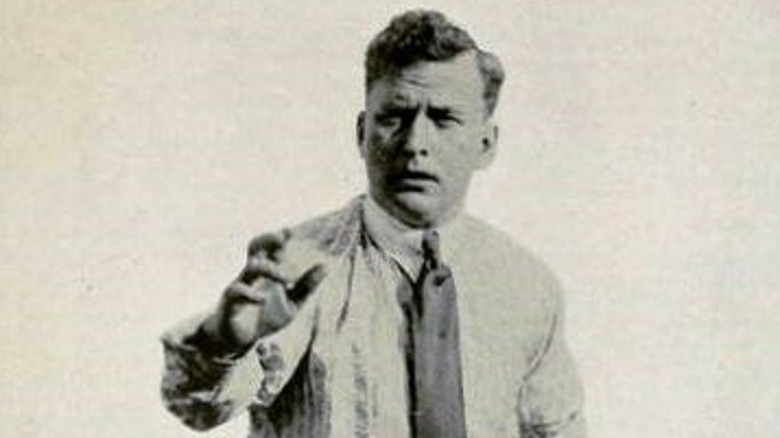

In the scrappy, DIY silent era, safety precautions were much lower down the list of priorities on busy sets than they are today. Particularly if you happened to be Buster Keaton (pictured). Keaton became famous for his daredevil stunts, and broke a few bones in the process. If you've seen the footage of the front of a house falling on a man, who happens to line up perfectly with a window, that's Keaton. Keaton and his contemporaries like Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd came up with inventive ways to minimize risk while still getting dangerous-looking shots. And according to the Guardian, Keaton sometimes stepped in for other, less daring actors. But typically, actors were expected to do their own stunts, without training.

Some actors embraced this rough-and-ready approach. Douglas Fairbanks, for example, became famous for his fight scenes and other swashbuckling stunts. But others were less thrilled. Gloria Swanson, for example, was made to dive into deep water, mostly naked, even though she couldn't swim. And in 1914, actress Grace McHugh and cameraman Owen Carter drowned while shooting "Across the Border."

Fire was also a hazard. Florence Lawrence, formerly known as the Biograph Girl, was injured in a fire on set. And actress Martha Mansfield was killed during a break when a lit match fell into the car she was sitting in, igniting her costume.

Hollywood stars injured on set were given addictive painkillers

Drug addiction was another of Hollywood's open secrets. Some stars started taking pain medication while recovering from injuries sustained on set, at the encouragement of their studios. If a lead actor couldn't perform, the set would have to shut down, and that meant losing money. Better to numb their pain enough that they could finish the shoot, and worry about the health consequences later.

Take the sad story of Barbara La Marr (pictured), for example. In 1923, the charismatic actress and screenwriter sprained her ankle while filming a musical number for the movie "Souls For Sale." According to the LA Times, she was prescribed heroin, and became addicted. She also used lots of cocaine. La Marr collapsed on a set in late 1925, and died a few months later, aged just 29.

Wallace Reid had a similar experience. He was prescribed morphine after sustaining serious injuries during a bloody accident that occurred while he was shooting a scene for "Valley of the Giants." He was praised for not missing even a day of work, but by the end of the shoot, he was addicted to the drug. He died of a morphine overdose in 1923. The studios were more than willing to prioritize healthy budgets over healthy stars.

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Prohibition-era audiences were scandalized by Hollywood's parties

Not all drug use started as medicinal. Drugs and alcohol flowed at Hollywood's freewheeling parties, despite the fact that the manufacturing, transportation and sale of alcohol had been outlawed in 1919 by the Eighteenth Amendment. Alongside booze, cocaine became the drug of choice for many of Hollywood's most famous stars, including slapstick pioneer Mack Sennett and his Keystone Kops.

Unfortunately, the party had to end some time. In 1921, Hollywood stumbled into an unwelcome spotlight, when beloved comedian Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle was put on trial for murdering actress Virginia Rappe, who had died at a boozy party. Arbuckle was eventually acquitted of her murder, but the media used his trial as an excuse to criticize Hollywood's decadent ways, the New Yorker reports. The scandal eventually contributed to calls for movie censorship.

The studios could protect stars from being photographed stumbling out of a speakeasy, but the abundance of drugs and alcohol took a toll on their health. Buster Keaton became addicted to alcohol, while Arbuckle and Norma Talmadge were both addicted to cocaine. Alma Rubens was committed to a mental asylum to "treat" her addiction to cocaine and heroin, but was arrested for drug possession a year later, and died of pneumonia a few weeks after that. Actress Jeanne Eagels died of a heroin overdose in 1929. The long hours and intense pressures that came with stardom, plus easy access to prohibited substances, made stars vulnerable to drug and alcohol abuse.

Whoever murdered this director was never caught

In February 1921, just months after Fatty Arbuckle's second trial (which ended in a hung jury), Hollywood was rocked by another murder. William Desmond Taylor, prolific director and head of the Motion Pictures Directors' Association, was found shot dead in his apartment. Robbery was ruled out as a motive: The killer hadn't even bothered to take the cash Taylor had in the apartment or on his body. As the Guardian reports, the first people to examine these clues were not the police, who weren't called until 12 hours after the body was found. Supposedly, the first people on the scene were Paramount executives.

It didn't take long to draw up a list of suspects. Actress Mabel Normand was the last person known to have seen Taylor, and his rumored lover. Many people thought Taylor was killed by Charlotte Shelby, the mother of another alleged lover, Mary Miles Minter, who herself was also accused of the murder. There were also claims about occult practices, and a possible gay love affair that turned deadly.

The investigation incidentally revealed that Taylor had an abandoned wife, although she wasn't a prime suspect. Comedy king Mack Sennett, Normand's boss, was, however, and supposedly even confessed on his deathbed. Sennett apparently claimed that he didn't like that Taylor was gay (making it a homophobic hate crime), and wanted to protect Normand from accessing drugs through Taylor. However, 300 other people also confessed. The murder was never solved.

The death of a movie mogul is still unsolved

Producer and director Thomas Ince's name has been mostly lost to history, but at the time of his mysterious death on November 19, 1924, aged just 43, he was one of the most influential people in Hollywood. In the days before his death, Ince attended a party on newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst's yacht. Other guests included Hearst's lover Marion Davies, and Davies' rumored lover Charlie Chaplin. By the end of the trip, Ince was dead, rumored to have been shot, and Hearst and Chaplin were denying they had been present.

So what happened? According to the LA Times, the version supported by Ince's widow claims that Ince had a heart attack on the yacht, and after an emergency docking in San Diego, he was taken home by train, where he died.

However, this story was complicated by Chaplin's secretary's claim that Ince had a bullet wound. Also, the accounts published by Hearst's newspapers were littered with obvious inaccuracies. New stories emerged. After stumbling on Chaplin and Davies together, Hearst had shot Ince by mistake while aiming for Chaplin. Or maybe he'd found Davies with Ince. Public pressure forced the District Attorney to examine the case — but not wanting to open Hearst up to accusations of flouting Prohibition, he quickly closed the investigation. As Snopes points out, rumors of murder persist to this day — and in a meta twist, the story has been turned into a movie, 2001's "The Cat's Meow."