10 Things About Embalming Your Funeral Director Won't Tell You

Death is a mystery to everyone, in both the metaphysical and the practical sense. No one knows with certainty what happens after we pass on, and the last thing anyone wants to do when someone close to them dies is engage in a crash course on the funeral business. At such an emotional time, most of us just want to celebrate our loved one's life and have as few details to deal with as possible.

As a result, most of us know precious little about the process of death in the modern world. It's all abstracted from us — hospitals transport the remains to funeral parlors, where sympathetic funeral directors guide us through our options. One of those options is almost always embalming, a process that restores something like the appearance of life and preserves the human body for the viewing or memorial service.

Embalming has become so common that few people actually question it, but even fewer understand the actual process. And our reluctance to talk about death and how we deal with a dead body works in favor of funeral directors, who very much doesn't want to have those conversations with you. Here are 10 things about embalming that your funeral director won't tell you.

Embalming doesn't preserve the body indefinitely

If you've ever seen an embalmed body, you might be forgiven for assuming that the posed, waxy countenance of the recently departed means that they will be preserved forever. Some people assume that the embalming process transforms a corpse into a statue of sorts, and that if properly stored, the departed will look fresh and lifelike for a very long time.

According to author and funeral director Caleb Wilde, however, that just isn't the case. Wilde explains that the purpose of embalming is to "reduce the presence and growth of microorganisms, to retard organic decomposition, and to restore an acceptable physical appearance." The words reduce and retard give the game away: none of the effects of embalming are permanent. The Funeral Consumers Alliance notes that the body will still decompose after embalming, and the rate of that decomposition depends on variables like the strength of the chemicals used and the humidity and temperature of the burial site.

The Daily Undertaker explains that the amount of formaldehyde — the most common embalming chemical in use — can vary. Bodies embalmed for funerals receive a lower amount in order to maintain a lifelike skin tone and texture. Bodies preserved for medical study, for example, receive a more powerful treatment. This keeps them "stable" longer, but at the cost of their visual appearance. But no amount of formaldehyde or other chemical will preserve a body forever.

The body's fluids just go to the sewer

The Morning News explains the process of embalming a body. Aside from cosmetic considerations, it says that the main goal is to remove the bodily fluids and replace them with preservative chemicals. You might think that since the fluids we're talking about include blood, feces, urine, and other stuff, there must be a special procedure for disposing of it all, and that it's probably considered hazardous.

And you would be wrong. In his book "Grave Matters," author Mark Harris notes that one 90-minute embalming produced 120 gallons of funeral waste that went directly down the drain into the local sewage system. This waste was totally untreated, and contained both bodily fluids and excess chemicals. Harris also notes that if the body harbored any disease, it too was flushed into the community drainage system.

Many communities allow this practice, and even in areas where it isn't explicitly allowed it's still frighteningly common. Gizmodo reports that when Austin, Texas discovered that funeral homes were draining waste into the public sewers, the Texas Funeral Service Commission executive director noted that this was officially taught in mortuary educational programs statewide. He also argued that typically there's little danger as the fluids and chemicals resulting from embalming are pretty diluted by water.

It is usually not required

If you've ever been involved with arranging a funeral, you may know that some funeral directors act as if embalming is assumed, and might even imply it's required for public health and safety. In almost every case this is pure hogwash — embalming is almost never required by law, and you can almost always choose not to do it.

The most obvious reason you would skip the embalming, as noted by author Caleb Wilde, is because the body is being cremated. When the body is set to be burned, no preservation is necessary. As noted by Fox News, if you choose to have an immediate burial with no viewing, there's also no need for embalming — in most cases the body can be preserved adequately via refrigeration. There may be state laws that require embalming under specific conditions, however.

The funeral home you hire may have a policy regarding embalming, which is its right as a private business, but you can take your business elsewhere, and not every state even requires you to hire a funeral director at all. You may also be able to hold a private viewing that would not require embalming as long as it was organized quickly. Funeral directors tend to promote embalming and may even allow you to assume it's legally required due to the obvious profit motive.

Embalming a body doesn't make it safer

One reason that's often offered to justify the cost and trouble of embalming a body for a memorial viewing is health and safety. It's easy to believe that being in the same room with a naturally decaying corpse might pose a threat. After all, decomposition is messy.

But as author Mark Harris explains in his book "Grave Matters," there's very little evidence that embalming makes dead bodies any safer to be near. In fact, it's very possible that embalming is less safe than letting the decomposition process proceed as nature intended. Cutting open a corpse that's carrying an infectious disease, after all, is a surefire way to release that disease to everyone it comes in contact with.

As noted by the Funeral Consumers Alliance, while a typical human body is jam-packed with bacteria and other organisms, they are typically harmless. Almost none of this stuff poses a threat in the natural process of decay. The bottom line is that a dead body infected with a disease isn't more dangerous than a living body infected with a disease — and may even be less so as your chances of getting up close and personal with a cadaver are probably low.

It might stop us from moving on

Many cultures have a ritual component to death in which loved ones and members of their community gather to memorialize them. Often this includes having their body on display. This can strike some people as odd or morbid, but there may be a very necessary psychological factor in viewing the body.

Inverse notes that studies have shown people have an easier time accepting the death of a loved one (or even a pet) if they can see the corpse — especially if the corpse displays obvious signs of death. People who have little or no contact with the remains often experience "false positive" moments when they forget their loved one is deceased, and can experience grief and pain all over again. Author and funeral director Caleb Wilde explains that people who don't see the body often experience "complicated bereavement."

But as noted by author Sallie Tisdale in Time, the embalming process can actually inhibit the grieving process. The whole point of embalming is to make the deceased look almost lifelike, as if they are peacefully sleeping instead of dead. This can confuse someone grieving for them, compromising the necessary acceptance of the person's death.

Embalming fluid is very environmentally un-friendly

Many people assume that burying a body is just part of the natural cycle. Living creatures are organic parts of the living world, after all, and nothing could be more natural than a body decomposing and being absorbed back into the earth.

But as Business Insider notes, burying human bodies has a very negative impact on the environment — in part because of the embalming process. The chemicals that are pushed into a corpse to preserve it for a few days will slowly leech into the ground, potentially getting into groundwater.

The danger grows over time as not only the bodies but the coffins they're contained in decompose and fall apart. And it is hardly a new concern. According to Smithsonian Magazine, many communities are dealing with Civil War grave sites leaking 19th century embalming fluid into the ground. Back in those days, one of the main components was the poison arsenic, and now it's turning up in water tables. One study in Iowa City found that groundwater near an old cemetery had three times the legal limit of arsenic levels.

The bottom line, as explained by funeral director Caleb Wilde, is that the only environmentally friendly way to bury a body is to skip embalming.

It's kind of a recent phenomenon

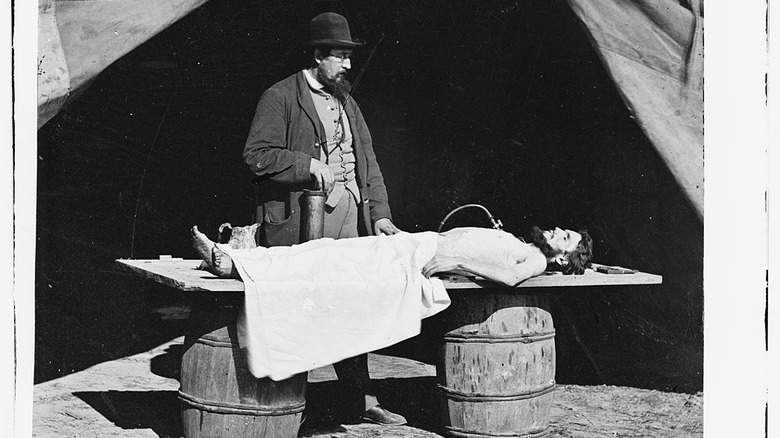

According to Britannica, embalming is a pretty ancient practice that goes back thousands of years. The ancient Egyptians famously practiced it on their Pharaohs and other important folks, after all. But it was usually reserved only for people considered to be really important, and wasn't widespread at all until the 18th century, when arterial embalming, the method of replacing blood and other fluids with a preservative, became more common.

In fact, according to "Grave Matters" by historian Mark Harris, in America there was intense opposition to embalming up until the mid-19th century. Many Americans considered it a violation of Christian principles. What changed everyone's mind was the Civil War — according to Time, so many men died far way from their homes in that conflict that a way to preserve their bodies for transport home was desperately needed, and primitive embalming became common. When President Lincoln was assassinated, his body was embalmed and traveled the United States, allowing people to see firsthand what the procedure could accomplish.

As Harris notes, the rise in popularity of embalming also led to our modern funeral industry. Families were always capable of washing, dressing, and burying their dead on their own. But embalming is a complex procedure requiring some surgical skill and medical knowledge — knowledge that people were suddenly willing to pay for. According to The Funeral Consumers Alliance, in the modern day only two countries commonly embalm their dead: Canada and the United States.

Embalming involves massage and moisturizing

While some might joke about resting when they're dead, very few people imagine that being embalmed resembles a trip to some sort of macabre spa. But the fact is the typical embalming procedure actually does resemble a kind of spa day.

As noted by the New York Times, when a body turns up on an embalmer's table, it's usually been a while since they died, so a process of muscle stiffening called rigor mortis sets in (per Yale Scientific Magazine). That means the body is quite stiff and resistant to posing, so one of the first things an embalmer will do is massage the body to loosen up its limbs and facial features so they can be manipulated into the restful, peaceful pose and expression you see at the viewing. The Guardian reports that a secondary massage may be performed when the embalming fluid is introduced in order to facilitate its circulation.

Being dead is hell on your skin, as you might imagine. Author Mark Harris notes in his book "Grave Matters" that the embalmer will also rub in moisturizer in order to keep the skin on the body's face and hands from drying out too much. The embalmer will also shampoo the body's hair and perform other cosmetic treatments like manicures and the application of makeup.

The facial features must be set

If you've ever been to a wake or viewing of a dead body, you may have observed the peaceful expression on the deceased's face. As you might imagine, people don't naturally look like that when they die. The embalmer has to create that expression through a process known as "setting the features."

In his book "Grave Matters," author Mark Harris notes that setting the features has to be done before the actual embalming procedure, which stiffens up the skin and muscles, making it more difficult to alter them. According to the Guardian, setting the features begins with closing the eyes and packing the mouth with cotton to ensure a "natural" look.

In her book "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes," mortician and author Caitlin Doughty explains that the deceased's ears, nose, and mouth must be cleaned out using cotton swabs — and there's a risk of the body "purging" fluids from the stomach as this process is going on. Things can get pretty weird from there. Eyes tend to slide open and jaws tend to drift, so plastic eye-caps are placed on the eyeball to both maintain its shape and hold the lids closed. Using a device called a needle injector, the jaw is wired shut. If that fails to hold the jaw in place properly, the embalmer will often resort to superglue.

Orifices must be plugged up

After death, the human body begins the decomposition process almost immediately. While embalming is designed to delay the obvious effects of this for a short time, it doesn't do anything to reanimate the body. Muscles remain slack, and that means the usual ways the body keeps stuff inside aren't working any more. As noted by author Tomás Prower in his book "Morbid Magic," morticians have a very simple term for the result: leakage. Mortician Caitlin Doughty notes in her book "Smoke Gets Your Eyes" that bodies often regurgitate fluids while being worked on, which is a highly unpleasant experience even for people used to handling corpses.

The Funeral Consumers Alliance explains that bodily openings like the anus and vagina will be stuffed with cotton or gauze to prevent leakage. Author Mark Harris notes in his book "Grave Matters" that many funeral supply companies offer "A/V closure" devices that can be inserted to create a tight seal.

According to author Christine Quigley in her book "The Corpse," sometimes an embalmer will go beyond cotton and plastic plugs and surgically close the esophagus and trachea entirely to prevent any fluids from leaking out of the body.

There's often a gas problem

Becoming an embalming professional isn't easy. According to author Christine Quigley in her book "The Corpse," morticians train for up to 5,000 hours in order to be licensed. Indeed reports that embalmers need an associate's degree in mortuary science at minimum, and then must serve in an apprenticeship before applying for their official embalmer license.

So the person embalming bodies is a highly trained, highly educated individual. But there are aspects of the embalming process that no amount of training can prevent. According to mortician and author Caleb Wilde, one of those aspects is something called tissue gas.

The Health Board explains that tissue gas is caused by a bacteria called Clostridium perfringens. This bacteria occurs naturally in the body, but after death can experience explosive growth because the immune system stops functioning. Once this process begins, the body will swell and discolor very quickly, filling like a balloon. Wilde explains that once this happens, not only is it impossible to make the body look presentable, tbut he bacteria can often spread wildly, infecting other bodies. It can even get on instruments and linger, spreading to the next body the embalmer works on.

Once tissue gas begins to spread, it can be very difficult to control. There are antibacterial agents that can be added to the embalming fluid, but often an outbreak of tissue gas requires that the body be buried or cremated quickly to stop the spread.

There's something called skin slip

In the list of terrible things that can happen during the embalming process, one of the most horrifying is definitely skin slip. According to ScienceDirect, skin slippage is a "loosening and sloughing of the epidermis (i.e., the skin)." In other words, the skin simply slides off the body. Medical News Today notes that when this happens on the corpse's hands, the skin can come off in what's known as a "glove formation" which is exactly what you think it is. In fact, the skin often comes off the hands so cleanly that according to author Ann Bucholtz in her book "Death Investigation," the glove can be used to get fingerprints from the body.

Author Carl Lewis Barnes notes in his book "The Art and Science of Embalming" that skin slippage is one big reason that formaldehyde is used in modern embalmings. The chemical actually tans the skin, hardening it and making it more rigid. This makes it much more difficult for the skin to become separated from the body and slide off.

Aside from the cosmetic concerns of skin slippage, in their book "Dealing with Death" authors Micheal and Jennifer Green explains another problem it can cause: excess fluid leakage. The skin serves to hold the body together and acts as a container for the rapidly increasing fluids inside the corpse, so slipped skin can allow those fluids to leak everywhere.