The Tragic Komagata Maru Incident Explained

In the first year of the COVID pandemic, it's estimated that EU member states illegally pushed back against at least 40,000 asylum seekers. These illegal operations are also linked to the deaths of over 2,000 people. Meanwhile, in the United States, border patrol kept up to 30,000 people from seeking asylum in September 2021, with the border patrol agents seen on horseback whipping asylum seekers with their reins.

The enforcement of immigration law has a proven history of racism in both the United States and Europe, but Canada often finds itself conveniently left out of such conversations, despite the fact that its own history of racism in immigration policies is intimately tied with those of the United States and Great Britain.

The Komagata Maru incident is just one such example of racism in the history of Canada's immigration policy, in which Indian immigrants were rejected by the Canadian government and then subsequently massacred by the British government. And people of Indian descent weren't the only ones singled out in Canada's immigration policies. Canada imposed a $500 entry tax on all Chinese immigrants, and also imposed restrictions on Japanese immigrants as well. But the Komagata Maru incident isn't only about immigration. It's also about a fight against colonial rule. This is the tragic Komagata Maru incident explained.

Who was Baba Gurdit Singh?

Baba Gurdit Singh, also known as Sardar Gurdit Singh, was born in 1860 in Amritsar, India during British rule. His grandfather, Rattan Singh, had fought against the British during their imperial takeover of India during the Anglo-Sikh Wars as a high-ranking military officer in the Khalsa Army.

When Gurdit Singh was young, his father went to Malaysia, then known as British Malaya, where he ended up settling down as a contractor, while Gurdit Singh continued his schooling in Amritsar. According to Sikh History, Gurdit Singh ended up leaving school at an early age due to the harsh treatment he received from a teacher. However, around the age of 13 he was able to privately receive enough of a primary school education to be able to exchange letters with his father, who was still in Malaysia.

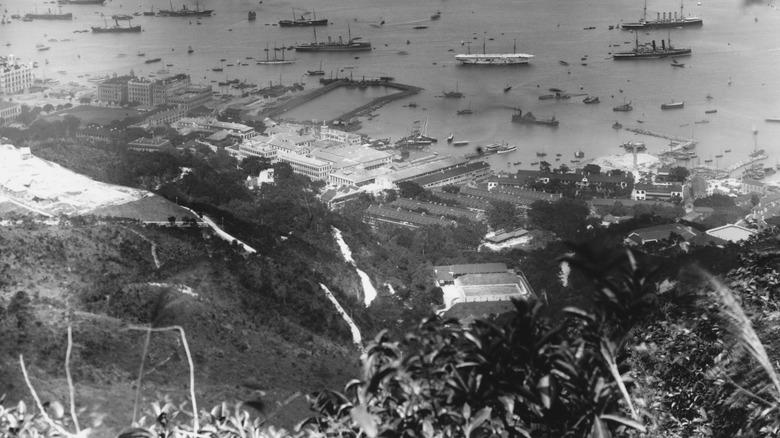

In "From Policemen to Revolutionaries," Yin Cao writes that Gurdit Singh soon followed the path of his father, traveling to both Malaysia and Singapore in the 1880s and becoming successful as a businessman in the food industry. In Malaysia, he also spoke out against forced labor, writing to the government about officials who forced villagers to work without payment. When the government never wrote back, Gurdit Singh encouraged villagers to stand up against and refuse forced labor. By December 1913, Gurdit Singh's work had taken him all the way to Hong Kong, then known as British Hong Kong.

What was the Ghadar Movement?

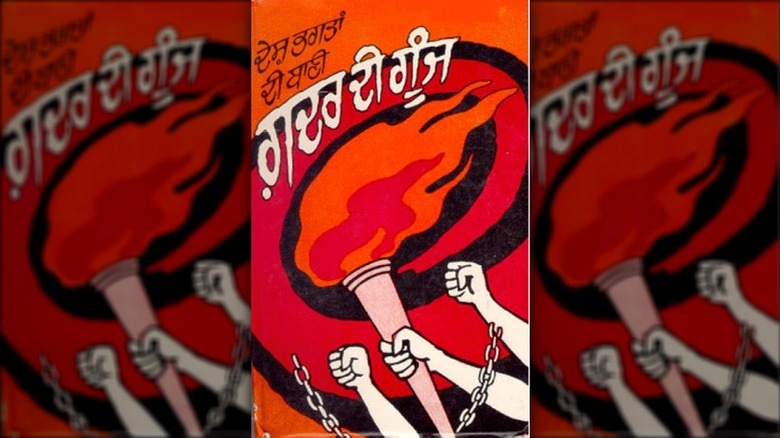

As British rule in India transitioned from rule by the East India Company to rule by the British Crown, Indian immigrants across the world were unsettled. In response, several organizations were formed outside of India "dedicated to supporting self-rule in India," according to The Pluralism Project.

One of these organizations, the Ghadar Party, was organized in California by Lala Har Dayal Singh Mathur, Sohan Singh Bakhna and Pandit Kanshi Ram in 1913. The Wire writes that the movement was religiously diverse, composed of Hindus, Sikhs, Muslims, and Parsis, but they were also relatively elitist. But as the movement expanded, rural Sikh farmers in California began to make up a majority of the party. Pushing newspapers in both Punjabi and Urdu, the Ghadar Party was able to recruit thousands of members outside of India who were invested in supporting the overthrow of British rule in the country. With thousands of members, the Ghadar Party decided to add their physical support to the cause of Indian self-determination while Britain was preoccupied with World War I. Members were to be sent to India in groups with money and weapons.

In response to the Ghadar Movement, and "in direct response to the anticipated arrival of the Komagata Maru" the British passed the "Ingress Into India Ordinance," according to Professor Renisa Mawani. This ordinance granted sweeping powers to the police, allowing them to stop, search, arrest, and detain anyone who was suspected of being anti-British.

Immigration to Canada from British India

Although there were only a few thousands South Asians in Canada at the beginning of the 20th century, racist lobbies pushed to stop people from immigrating to Canada from India. According to The Canadian Encyclopedia, as a result, Canada passed two regulations amending the Immigration Act in 1908 that for all intents and purposes were meant to keep people from Asia from entering Canada.

The first regulation was known as the "Continuous Journey Regulation," which stated that Canadian immigration officials had the option to block someone's entry into Canada if they didn't come using a continuous journey from their country of origin. The Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 writes that essentially targeted people who were coming from India and Japan, since there simply wasn't an option for direct passage to Canada for those countries on the main immigration routes.

The second regulation gave Canadian immigration officers the power to refuse entry to any person of Asian descent who had less than $200 upon arrival, "eight times the amount required of white immigrants." Although neither of these regulations singled out people from India specifically, which meant that "British imperial officials in India could deny the existence of any laws in Canada that barred Indian immigration," they effectively suppressed immigration from India. The regulation was challenged on several occasions, including in 1914, when the Komagata Maru had made its way to Vancouver's Burrard Inlet.

Chartering the Komagata Maru

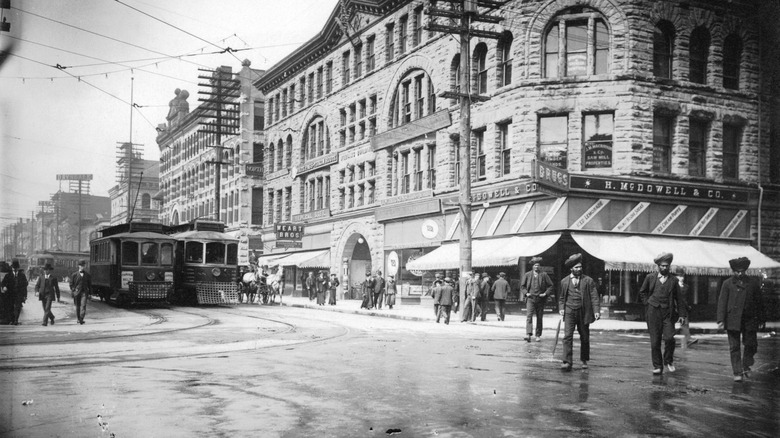

During his travels to Hong Kong for business, Gurdit Singh would visit the local gurdwara, places of assembly and worship for Sikhs. According to The Canadian Bazaar, Gurdit Singh met many Indian people at the gurdwara who found themselves stranded in Hong Kong because none of the ships going to Vancouver, Canada would allow them passage.

After Gurdit Singh's help was sought due to his connections and influence, he decided to charter a ship for Indian passengers and sail it to Canada in 1914 in order to challenge their immigration laws. Initially, he wanted to charter a ship directly from India, but because the Government of India was worried that the ship would violate Canada's immigration laws, Gurdit Singh's application to charter a ship was rejected, according to "From Policemen to Revolutionaries."

Canada's immigration laws took a beating around the same time in November 1913, when the British Columbia Supreme Court ruled, in the case regarding the passengers of the Panama Maru, that the continuous journey and $200 requirement regulations were invalid, Times Colonist reports. Prime Minister Robert Borden's cabinet soon rushed in to reword both regulations so that they "conformed to the immigration law." As a result, when the Komagata Maru was to arrive in May 1913, they would face a more arduous legal battle, as would J. Edward Bird, the lawyer who represented the passengers of both the Panama Maru and the Komagata Maru.

The Komagata Maru sets sail

Around February 1914, after Gurdit Singh began advertising in Hong Kong about passage to Canada, he finally found a ship to charter, the Komagata Maru, from a Japanese company. Gurdit Singh chartered the Komagata Maru for 11,000 Hong Kong dollars per month for approximately a six-month journey.

The Komagata Maru was scheduled to depart in March 1914, but two days before the departure date, Hong Kong Police arrested Gurdit Singh "for selling tickets for an illegal voyage," writes South Asian Canadian Heritage. However, Gurdit Singh was released on March 24, 1914, and was given permission to set sail on April 4. However, before giving the ship permission to sail, Governor of Hong Kong F. W. May had telegraphed both London and British Columbia to let them know that "Indian Sikhs have chartered steam from here to British Columbia," according to "The Voyage of the Komagata Maru."

On April 4, 1914, the Komagata Maru left Hong Kong with roughly 150 Sikh passengers. The ship would stop at Shanghai, Moji, and Yokohama to pick up more people who wanted to immigrate, gathering a total of 376 other passengers to sail to Vancouver, according to The Canadian Bazaar. One day before the Komagata Maru arrived, Sir Richard McBride, Premier of British Columbia, stated, "To admit Orientals in large numbers would mean the end, the extinction of the white people. And we always have in mind the necessity of keeping this a white man's country."

Arriving in Vancouver

After almost two months at sea, the Komagata Maru arrived in Vancouver on May 23, 1914. However, the Canadian government tried everything they could to prevent Gurdit Singh and his passengers from entering Canada. When the Komagata Maru arrived, officials wouldn't give Gurdit Singh permission to land, in order to keep him from accessing his banks and having the required funds to enter the country, writes the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. And when the passengers hired J. Edward Bird to represent them in court, immigration officials prevented Bird from meeting privately with the passengers.

The Komagata Maru was kept in Vancouver's Burrard Inlet for two months and on July 6, 1914, five judges ruled against Bird and decided that the passengers on the Komagata Maru wouldn't be allowed into Canada based on the regulations that Bird had, less than a year earlier, argued successfully against. In the end, all but 20 "who already had resident status" were denied entry into Canada. The time spent aboard the Komagata Maru was unpleasant as well, consisting of "fighting, no food on the ship, [and] lots of suffering," according to the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21.

On July 23, a little over two weeks after their appeal was rejected, the Komagata Maru was escorted by the HMCS Rainbow, a Canadian warship, all the way out of Canadian waters.

A massacre in Budge Budge

After being rejected by the Canadian government, the Komagata Maru turned back to spend another two months sailing all the way back to India. The Komagata Maru reached Kolkata, then known as Calcutta, on September 26, 1914, according to South Asian Canadian Heritage. As they approached, they were ordered to stop by a European gunboat. The gunship ended up escorting the Komagata Maru to Budge Budge Ghat, where police seized the ship. According to The Canadian Bazaar, after being forced off the ship, Gurdit Singh and his passengers were told to board a train in the railway station. But they refused, "saying that they are now in their own country and free to go where they want."

Meanwhile, British authorities believed that the passengers of the Komagata Maru were part of the Ghadar Movement and when they arrived, they started asking for Gurdit Singh. When the former passengers of the Komagata Maru refused to answer, the police tried to take Gurdit Singh's six-year-old son, who was among the passengers.

The passengers refused to let the child be taken and as a fight broke out, policemen fired into the crowd of passengers. Up to 22 people were killed and at least 40 others were injured during the police assault. According to the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, the rest of the surviving passengers ended up being imprisoned and dozens remained unaccounted for.

Baba Gurdit Singh in hiding

Gurdit Singh and his son were able to avoid capture during the Budge Budge riot and escaped with four other men. In an attempt to keep his son safe, Gurdit Singh sent him to the Sarhali village to live with his grandfather Hukam Singh. The Canadian Bazaar writes that Gurdit Singh lived in hiding for almost seven years in an attempt to avoid the authorities, who blamed him for the massacre that had occurred.

According to Komagata Maru Journey, while Gurdit Singh was in hiding he met with several nationalist leaders, but even they had a negative view of the Komagata Maru incident and he had to fight against "the suggestion that he and the passengers had been the authors of their own misfortune." During this time, he started writing his version of the incident in a serial publication. The subsequent book was titled "Voyage of Komagata Maru or India's Slavery Abroad."

Gurdit Singh's eventual capture

Gurdit Singh remained in hiding until 1922, according to Canadian Sikh Heritage, when Mahatma Gandhi encouraged him to give himself up "as a true patriot." In "Across Oceans of Law," Renisa Mawani writes that Gurdit Singh hoped that a court hearing would allow him to reveal the full story of the passengers of the Komagata Maru, especially "Canada's hideous crime under the cover of law."

After giving himself up to the authorities on November 15, 1921, during an annual Sikh festival in order to ensure maximum publicity, the court ultimately found Gurdit Singh guilty of defrauding his passengers. In the end, Gurdit Singh ended up being imprisoned for five years. After being released from imprisonment, he worked with Gandhi on the Indian independence movement.

Gurdit Singh died in 1954, at the age of 95, living long enough to see both Indian independence and a monument to the Komagata Maru raised at Budge Budge in his lifetime.

Inspiring support for the Hindu–German Conspiracy

By the time the Komagata Maru was told to leave Canadian waters, its story had already spread amongst the Indian community around the world. According to "Underground Asia," meetings for organizations that were concerned with the liberation of India were "attended by hundreds of people."

In "Trials that Changed History," M.S. Gill writes that around August 1914, Ghadrites, members of the Ghadar Movement, also set sail for India. And on the way, when they found out in Penang what happened to the passengers of the Komagata Maru at Budge Budge, they knew that they were in for a similarly cold welcome. Upon arrival, all 8,000 aboard the ship were arrested. Out of the 8,000: 5,000 were released; 2,500 were restricted to their villages; and 400 were kept imprisoned.

News of the Budge Budge massacre also led to the galvanization of what became known as the Hindu–German Conspiracy. According to Scroll.in, many were motivated "by anger at the racism and exploitation they witnessed and were subject to" and joined the Ghadar Movement to fight for India's self-determination. The Hindu-German conspiracy involved a "secret shipment of arms and rebels" from the United States to India. However, the plot failed and was revealed in 1917 when some of its key participants were arrested. The subsequent trial against nine Americans, nine German citizens, and 17 Indians ended up lasting 155 days and cost the United States government $450,000.

Canada issues a formal apology

In 2016, Prime Minister of Canada Justin Trudeau issued a formal apology in the House of Commons for the 1914 Komagata Maru incident. Trudeau stated that "Canada does not bear alone the responsibility for every tragic mistake that occurred with the Komagata Maru and its passengers, but Canada's government was without question responsible for the laws that prevented these passengers from immigrating peacefully and securely, for that, and for every regrettable consequence that followed, we are sorry," per CBC News.

This isn't the first time that a Canadian Prime Minister has issued an apology for the Komagata Maru incident. In 2015, Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologized while speaking to a crowd of 8,000 people in Surrey, British Columbia. However, as soon as Harper left the stage, members of the Sikh community like Jaswinder Singh Toor, president of The Descendants of Komagata Maru Society, denounced his apology as "unacceptable" and said that the apology should've been made formally on the floor of the House of Commons.

According to the City of Vancouver, the Vancouver City Council also issued a formal apology on May 18, 2021. The formal apology reportedly comes out of a 2019 Council decision of engaging in a "broader ongoing effort to recognize historic discrimination against the South Asian community."