Attica's Most Notable Inmates

The United States, it turns out, is home to an almost mind-boggling number of correctional institutions. Between federal, state, and local facilities alone, the Prison Policy Initiative says that as of 2020, there were 6,849 jails and prisons in the country, housing somewhere upwards of 2 million people. That's a ton of prisons, and among those, there are only a few that have some serious name recognition. They're places like Alcatraz, Sing Sing, and, of course, Attica.

Attica was catapulted into the headlines in 1971, when inmates — sick of inhumane treatment — rose up and took control of the prison. September 9 to the 13 was a standoff between inmates — with hostages — and state police, and it didn't end well. Negotiations weren't working, and after governor Nelson A. Rockefeller gave the go-ahead for state troopers to storm the place and retake the prison, it kicked off a bloody firefight that left 29 inmates and 10 hostages dead, and a further 89 people wounded (via History).

Since then, Attica has been synonymous with the problems inherent in the country's correctional system, and that's made it easy to overlook what else it is. Built in 1931, Prison Insight says the maximum-security facility has long been used to house some of the deadliest and most violent men in the state. Around 2,000 people can be held there at any given time, and over the years, some of the most notorious criminals in the nation's history have walked through Attica's gates.

Mark David Chapman

In 1972, John Lennon released "Some Time in New York City," which included the track "Attica State." Lyrics included (via Genius) "Free the prisoners, Jail the judges, Free all prisoners everywhere, All they want is truth and justice, All they need is love and care," and that's kind of ironic, given that the man who murdered him eight years later would ultimately be sent to Attica.

It was one of the most shocking assassinations in music history: On December 8, 1980, Mark David Chapman shot and killed former Beatle John Lennon. By the time police arrived, he was still at the scene, calmly reading "The Catcher in the Rye" and waiting for his arrest. He was found guilty and given a sentence of 20 years to life: By 1981, he was in Attica — where, Oregon Live says, he would spend the next 31 years, before being moved to the nearby Wende Correctional Facility. According to Newsweek, he'd spent much of those 30+ years working in the kitchen, the library, and as a legal clerk.

Chapman has been denied parole every time he's been up for it, and in 2020, he apologized (via the BBC) for what he'd done. He said (in part): "I have no excuse. This was for self-glory. I think it's the worst crime that there could be to do something to someone that's innocent ... It was an extremely selfish act. I'm sorry for the pain that I caused to [Yoko Ono]. I think about it all of the time."

David Berkowitz

It wasn't until the killer stalking New York City in the late 1970s left a signed note behind that he got the name "Son of Sam," and up until then, he'd been called the ".44 Caliber Killer." The shootings started with an attack on Jody Valenti and Donna Lauria in 1976, and it would come to an end when David Berkowitz was arrested on August 10, 1977. He pleaded guilty, saying he'd only been following instructions he'd been given by a demonic entity that spoke through his neighbor's dog. (Later, says Men's Health, he would go on to say he had actually believed he was paying a debt to Satan that would end his loneliness.)

Berkowitz was sentenced to Attica, and he was there by 1979. It was July of that same year that he was in headlines again, and The New York Times was reporting that after he was attacked by another inmate, he'd needed between 50 and 60 stitches to close a gash across his neck, back, and shoulder. He had been distributing water to prisoners in protective custody — who had access to a single razor blade at a time — and he refused to say who attacked him.

When World interviewed Berkowitz in 2020, he was no longer at Attica. High-profile, high-risk inmates tend to be moved often, and he was at Shawangunk Correctional Facility. He identified himself as a Messianic Jew, and reportedly spends his time in prayer, working for the chaplain, cleaning, and writing.

El Sayyid Nosair

When the Los Angeles Times did their piece on El Sayyid Nosair in 2013, they called him "the first Islamic jihadist to commit murder in the United States," and for that murder, he was sent to Attica. In 1990, Nosair shot and killed Rabbi Meir Kahane. Kahane was the head — and founder of — a group called the Jewish Defense League, and Nosair said, had "openly advocated genocide and ethnic cleansing." Nosair was actually acquitted of murder charges but ended up being handed the maximum sentence a judge could give him just based on gun charges, and that was 22 years. He headed to Attica, where he was — according to prosecutor Andrew C. McCarthy — "a star and a hero in the jihad."

That definitely wasn't the end of his story, though. In spite of the fact that federal agents closely monitored everything from his visits to other communications, Nosair would ultimately be named as one of the conspirators and planners of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing (via NPR). After the bombing, The New York Times said it quickly came out that two other inmates had given Nosair access to their phone codes, allowing him to call out under their identification numbers. After getting caught abusing phone privileges, he was moved to solitary confinement.

He later claimed that he absolutely couldn't have been involved in the bombing (because, he claimed, he was actually being trained to fight "Soviet forces in Afghanistan,") and was denied a new trial.

Sam Melvile

Sam Melville was arrested in November of 1969, says The New York Times, and it was in March the following year that he tried to flee from the Federal Courthouse where he was on trial as the explosives expert in a group accused of plotting to bomb six Manhattan buildings. Within months, Melville admitted that yes, he had been involved in a plot to bomb skyscrapers that included Chase Manhattan Bank, and went on to say, "I did place a bomb in the Federal Plaza."

The confession ended with a 13- to 18-year prison sentence, and although there was the potential he could be paroled before he hit that 18-year-mark, that wasn't going to happen. On September 15, 1971, Melville was back in the headlines — this time, The New York Times was reporting that he was one of the inmates that had been killed in the Attica prison riot.

Melville had been active in organizing the riot from the inside, writing treatises — like "An Anatomy of the Laundry" — and reaching out to his attorneys to describe "the basic terror that people live under in prison." He said that at the time the riots kicked off he had just spent several weeks in solitary confinement as a punishment for taking an extra piece of bread, and at the time he was killed by a sharpshooter, it was said that he was in possession of several homemade bombs, and was making a run for a 500-gallon fuel tank.

Joel Rifkin

Getting a glimpse into the mind of a serial killer can be a terrifying thing, and Oxygen's documentary "Rifkin on Rifkin: Private Confessions of a Serial Killer" is certainly no different. Rifkin has admitted to killing 17 women between 1989 and 1993, targeting sex workers who he picked up then killed. At the time he was arrested, The New York Times reported that his mother testified that once she had learned about the murders, she'd asked her son about them. "I did question my son, and he assured me there were no more than 17," she explained in front of the Nassau County Court.

After his first conviction in 1994, sorting out the other charges and sentences took another two years. It wasn't until 1996 that he went to his final sentencing, and his sentence for the murder of 25-year-old Iris Sanchez raised his finally tally to more than 200 years in prison.

He was originally sent to Fishkill, but when his old friend, former police officer Robert Mladinich, reached out to him and started the series of conversations that would ultimately be made into the Oxygen documentary, Fox News says he was at Attica. According to Biography, he was placed in solitary confinement after altercations with other inmates, where he stayed for four years. A 2000 lawsuit that claimed his rights were being violated by his treatment failed, and he was transferred to another prison, with other high-risk inmates.

Colin Ferguson

On December 7, 1993, Colin Ferguson boarded a Long Island Rail Road train, and then, he started shooting. When the incident was over, six people were dead and another 19 were injured, including a woman who had been seven months pregnant when she was shot (via ABC News.)

History says that while Ferguson's original lawyer claimed a defense of "Black rage" that had made Ferguson angry at everyone in the entire world — including himself — Ferguson fired that attorney. He later swore that it hadn't been him at all, but another man with the same name, a defense that fell through when he asked all the survivors who the shooter had been, and the 100% responded that it had been him. When it came time for sentencing, it was a hearing that lasted for three days and ended, says NBC, with Judge Donald Belfi giving him six consecutive life sentences.

In 2018, NBC reported that not only was the train car that was the location of the shooting still in active use, but Ferguson was, at the time, being held at the Upstate Correctional Facility. He'd been in Attica just a few years before, until he found himself back in court again on charges of trying to incite a riot. It was reported (via the New York Post) that on Sept. 11, 2011, guards at Attica had overheard him trying to get other inmates on board with killing guards. He was found guilty.

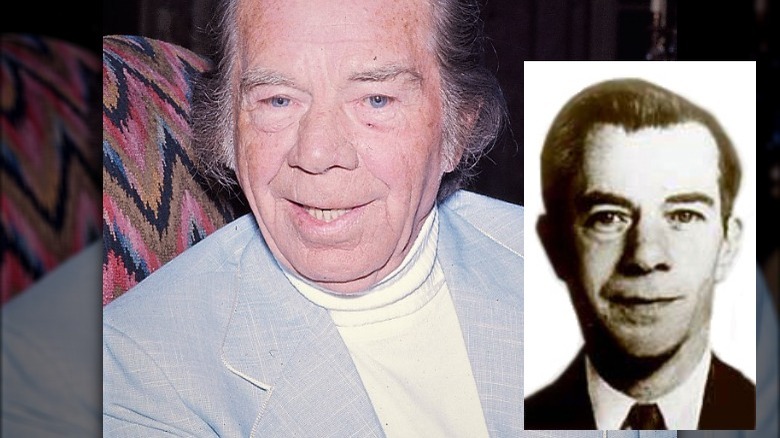

Willie Sutton

Willie Sutton is definitely the sort of criminal that might be described as "colorful," and his story's absolutely incredible. He was born in 1901, and according to the FBI, his life of crime came to an end when he was released from Attica on Christmas Eve in 1969. During those nearly seven decades, he robbed somewhere around 100 banks (along with the occasional jewelry store), stole millions, and escaped prison an almost ridiculous number of times.

Those attempts included his 1947 except from the Philadelphia County Prison. He was spotted by a guard, but when he yelled, "It's ok!," they allowed him to go on his way. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle says that he had pioneered what were essentially ground-breaking techniques for robbing banks, and when asked why he did it, he famously (reportedly) replied: "Because that's where the money is." He was finally added to the FBI's Ten Most Wanted list, and he was turned in to authorities in 1952. At the time, he still had a full life sentence and another 103 years left to serve, and another 30 years was tacked on to that. He would only spend another 17 years in jail, though, in Attica.

There's an epic footnote to this: After he was released, he was featured in a television campaign for New Britain, Connecticut, Bank and Trust Company, and he was the face of advertising their photo-bearing credit cards. He died in 1980 and was buried in his native Brooklyn.

Kendall Francois

Originally, Kendall Francois entered a not guilty plea when he was put on trial for the murder of eight women, and according to The New York Times, the angry reaction from the crowd — which included family members of his victims — simply made him laugh. While everyone's supposed to be innocent until proven guilty, there was some pretty convincing proof in Francois's case: Police found the bodies of those eight women in the house he shared with his mother.

He eventually pleaded guilty in what was a surprisingly controversial decision, as it would spare him from the death penalty that prosecutors wanted, but it would also keep the most gruesome, sordid details of the murders from being publicized. Just a few weeks later, he was sentenced to eight consecutive life terms. One woman — who escaped him when he started choking her and, after running to the police, was ultimately responsible for his arrest — told him, "I hope they kill you in prison." Given that parole was off the table, it seemed like he would die in prison — and he did.

He was sent to Attica to serve his sentence, but by the time he was incarcerated there, he had already been living with HIV for at least five years. In 2014, the Poughkeepsie Journal announced that shortly after being transferred to the medical unit of nearby Wende Correctional Facility, he died of what was being called natural causes.

Joseph Christopher

The holiday season of 1980 was anything but jolly, especially for Black men living in New York City. According to the New York Post, a stabbing spree that ended with four men dead and two others wounded was absolutely terrifying, but it made law enforcement wonder: Were these attacks connected to a similar rash of violence that had happened in Buffalo, just a few months prior?

In September, the city had been terrorized by a rash of killings. Four Black men were killed in random shootings, all separate incidents, all using .22 caliber bullets. Ultimately, they would learn that those killings were connected, as were the murders of another man in Rochester, and yet another Buffalo man, both of whom were killed at the end of December. Law enforcement got a tip from Georgia's Fort Benning Army base. They'd been having issues with a new recruit, who had attacked another man in the shower. After his arrest for that incident, he attacked several others — all of whom were Black or Puerto Rican.

Joseph Christopher was ultimately arrested and put on trial for the killings and attacks in New York. According to The New York Times, he insisted on representing himself, and after a series of verdicts, appeals, retrials, and psychiatric evaluations, was ultimately found guilty and handed a series of sentences that, the AP reported, would see him spending the rest of his life in jail. He did — he died in Attica, in 1993.

Valentino Dixon

At a glance, it seems straightforward. In 1991, a fight broke out in front of a Buffalo hot dog joint. One person, Torriano Jackson, didn't walk away. Police later arrested Valentino Dixon for the shooting, and he was ultimately sentenced to 38.5 years in prison — most of which he was going to be serving in Attica. That comes with a huge "but" though: Dixon didn't do it. After his arrest, another man confessed to the shooting, but no one ever followed up on the confession.

Dixon took solace in something he hadn't explored in a long time: art. And here's where things took an incredible (albeit slow) turn, when one of Attica's correctional officers asked him to draw one of the greens of the Augusta National Golf Club. He did, and was so inspired that he started drawing more golf courses, eventually writing to Golf Digest about his art, his conviction, and how important the works had become.

The so-called "artist of Attica" was ultimately featured in a piece at the magazine, and that got him some serious attention. In 2018, a group of Georgetown University students decided to reinvestigate the case, and they actually came up with enough new evidence that it started a review process. After 27 years in prison, Dixon was found innocent and released. He went on to start an organization called Art of Freedom, which advocates on behalf of those wrongfully convicted (via CNN). He gave Michelle Obama that original drawing.

H. Rap Brown/Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin

The National Archives says that when H. Rap Brown was campaigning to have his Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee join up with the Black Panthers, he didn't really have much luck in convincing others to see eye-to-eye with him. That likely had something to do with the criminal charges he was avoiding, and it wasn't until 1971 that he was finally arrested, put on trial for armed robbery, and sent to Attica.

The Los Angeles Times says that he only served four years of his five-to-15 sentence, and while he was there, he converted to Islam (and would later become a cleric), afterwards becoming known as Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin. After he was paroled, he spent some time living in Georgia and running his own grocery store in Atlanta, but he was back in court in 2002. This time, it was on murder charges, following a run-in with two police who were trying to carry out a bench warrant that had been issued after Al-Amin was accused of impersonating law enforcement and theft.

Al-Amin was ultimately convicted, and when he appealed to take the case to the Supreme Court, the Associated Press reported that they denied him.