The Myth Of The Furies Explained

Ever wish there were some conveniently all-powerful beings that could be tapped on the shoulder and told, "Yeah, that's the guy that wronged me! Sic 'em!"? Anyone living in ancient Greece or Rome would have known about exactly those sorts of beings, but they weren't exactly beholden to anyone or anything ... except, of course, the idea of justice. And no, it definitely wasn't justice of the swift sort. The Furies — known as the Erinyes in Greece and the Dirae in Rome — didn't just come down and deliver the sort of karma that involves a sudden and embarrassing death; they tormented guilty souls for all of eternity.

The idea of these divine, sometimes monstrous women who saw the wicked and the evil punished for their misdeeds is an incredibly old one, and according to The Eclectic Light Company, they've been immortalized in art for centuries. Usually, it's pretty dark stuff, transforming the guilty into the victim, and serving up a healthy helping of something that could be called vengeance instead of justice.

So, who are these women, and were they worshipped alongside some of the more mainstream gods? Absolutely. It's ... just a good idea, really.

They're the most ancient of Greek mythology

One thing most religions and belief systems have in common is the telling of creation myths — stories that explain how the world came into being. There are a few different versions of what's essentially the same story told by the Greek writers Hesiod and Homer, but according to The Collector, they agree on the basics. Along with early entities like Gaia/Ge (the Earth), Uranus (the Sky), and Nyx (the Night), there were the Furies.

It was in the seventh century B.C. that Hesiod wrote "Theogony," his treatise on the creation of the world. In it (via Gods in Ancient Greece and Rome), he told the story of the Titan (and eventual father of Zeus) Cronus. Cronus (pictured) led a revolt against his father, Uranus, and ended the whole thing by castrating him. When his severed genitals fell, they didn't just fall on the earth, they fell on the embodiment of the earth, Ge (or Gaia). Ge then gave birth to two groups of offspring.

The first was the giants — or Gigantes — who would later be such a thorn in the side of Zeus and the other Olympians. The second was the Erinyes, the personification of revenge and justice. (And a quick aside: Yes, this is the same castration that also created Aphrodite/Venus, making her the ... half-sister of the Furies? It's a weird story.)

There were originally a lot more

In the original stories, there was never a concrete number of Furies that were born from this ultimate act of rebellion by a son against his father (a detail that becomes important later in their story). It wasn't until Virgil was writing — which the Poetry Foundation says was around 38/37 B.C. — that the Furies were named and reduced in number to just three.

He describes them in "The Aeneid" (translation by Robert Fagles, via Allen Fisher), starting with Tisiphone. She sits at the gate of Tartarus, perched on the top of a tower overlooking hell's River of Fire, and "crouching with bloody shroud girt up, never sleeping, keeps her watch at the entrance night and day."

Then there's Allecto. She's called the "mother of sorrows," loathed by her sisters, and when she's summoned, she descends on the home of King Latinus, plucks a snake from her hair, and drives it into the chest of the queen. She feels absolutely no pain, but "the horror drives her mad to bring the whole house down" as the snake envelops her.

And finally, there's Megaera, who heads to earth and, seeing her target, transforms into a tiny bird that sings a song that seizes the soul of anyone who hears it, filling them with the kind of dread that can ruin even the bravest. She attacks, fluttering and screeching, and the sister of her target laments that there's nothing more she can do for her brother.

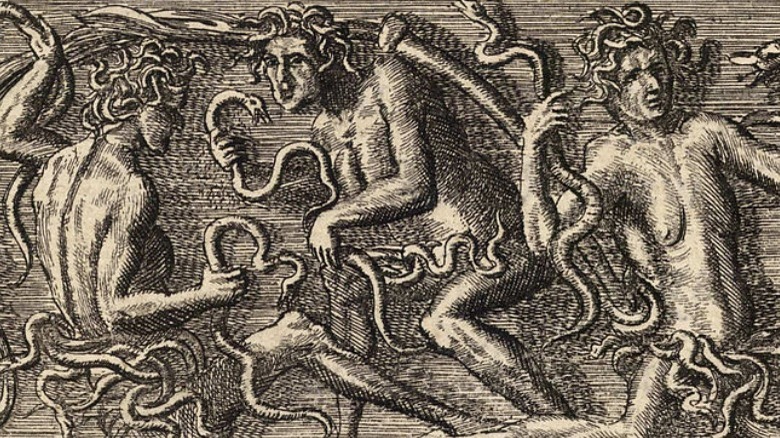

Here's what they looked like

Early descriptions of the Furies made it clear that anyone who caught a glimpse of them could tell exactly what they were in for.

In the fifth century B.C., Aeschylus described them (via Theoi) as being dressed entirely in black, and being covered with slithering snakes. He likened them to the Gorgons, a trio of winged demons with snakes for hair. (The most famous was the only mortal one, Medusa.) Strabo later elaborated, saying they wore long, floor-length cloaks and belted tunics, and walked with the help of canes. Ovid gets super graphic in his "Metamorphoses," describing the white hair of Tisiphone, her blood-soaked torch, and her bloody, gore-covered robes. He made their snakes living, venom-spitting entities of their own, with some crawling freely over and around them, and others tangled in their hair. They were associated with the screech-owl as well as with snakes, along with the yew tree.

Interestingly, Pausanias — who wrote the travelogue "Description of Greece" in the second century A.D. — noted that texts described them as bloody, snake-wearing demons. But when they appeared in murals and in imagery connected to their cult, they were often shown as having a generally human form, massive wings, and were often clad in boots and a short hunting tunic, similar to the devotees of Artemis.

The Furies were about more than just vengeance

Here's where the Furies often get misunderstood. While it's true that they were responsible for delivering vengeance — or justice, depending on your point of view — they were also, by extension, seen as protectors of the innocent.

World History Encyclopedia says that they were particularly concerned with the protection of certain people, particularly parents and the oldest siblings of a family. Should a mother, father, or any elder sibling issue a curse on anyone else, the Furies were likely to listen. And that kind of makes sense, given that they were born after a son cut off his father's genitals. They were fiercely protective of those who existed on the fringes of society, and they were also the divine beings that acted as a sort of guarantee when anyone swore an oath to another. Anyone who didn't keep their word would very quickly realize that was a terrible idea.

For obvious reasons, they were also associated with the appearance of bad omens. Hesiod and Virgil both wrote (via Theoi) that the "fifth day" was the day they attended the birth of Horkos, so that was unlucky. The appearance of a screech-owl was said to herald their inevitable arrival, and a solar eclipse was said to occur when the Furies blotted out the sky with their swooping darkness.

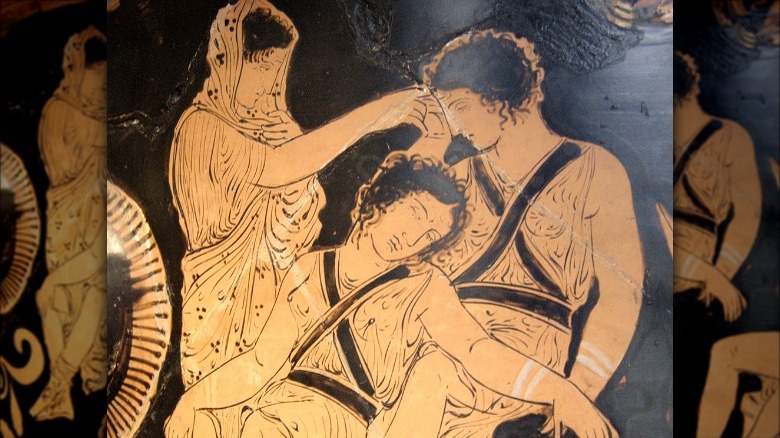

Orestes was their most famous victim

The Department of Greek and Latin at University College London calls the story of Orestes one of the most widely depicted tales in classical art, and it allows the Furies to show just what they're capable of.

Aeschylus's Orestes trilogy — "Agamemnon," "Libation Bearers," and "Eumenides" — tells a story that's connected to the Trojan War. Before the Greeks could head out to Troy, they needed to appease Artemis. It's unclear why, says "Mythology Unbound", but the answer was the sacrifice of Agamemnon's daughter, Iphigenia. Aeschylus' trilogy picks up as Agamemnon returns from war. His wife, Clytemnestra, sends their son Orestes away, then kills her husband for sacrificing their daughter. The second part picks up when Orestes has aged up into his late teens, and Apollo tells him he has to avenge his father by killing his mother. He does, and in doing so, calls down the Furies.

The Furies are particularly offended by anyone who commits crimes against their family and proceed to drive Orestes mad. Even Apollo is powerless to step in and call them off, but he does help Orestes get to Athens for a trial, overseen by Athena. The vote is split, and when Athena casts the deciding vote, she votes for Orestes' innocence. It's still not enough to dissuade the Furies, and they only agree to show mercy if they are given a place of honor in the shrines of Athens. They are, and become known as "The Kindly Ones."

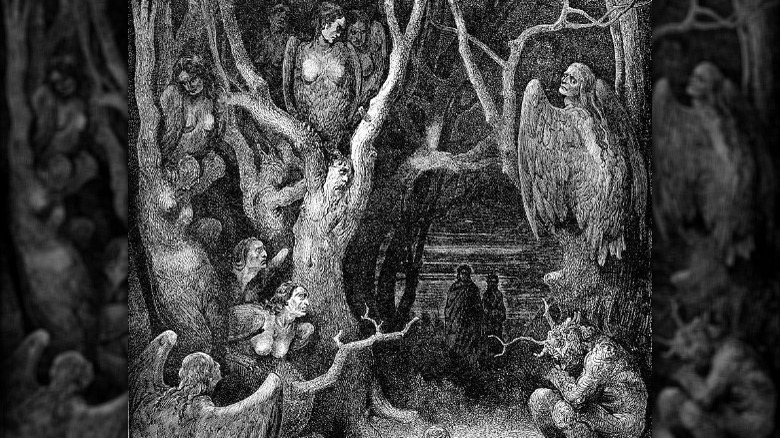

The Furies in hell

The Furies had a few other duties, too: They didn't just torment the living. They were also the ones responsible for seeing the souls of the damned delivered to their particular place in the underworld, where they would suffer continued torment for the rest of eternity.

As The Eclectic Light Company says, the Furies weren't bringing fire and brimstone down on mortal men and women all the time — when they weren't being dispatched to the world of the living, they slept in the underworld. Scores of classic pieces of art from masters like Jan Brueghel depict the Furies in their place in hell, and they show up in Dante's "Inferno," too. When they appear in the Fifth Circle (via the University of Texas at Austin), Virgil introduces them, and for the first time, he's not as all-powerful and invulnerable as Dante thought he was.

The ancient stories said that when someone died, they went before a trio of judges that would decide where they were going to spend eternity. Whatever was decided, it was the Furies who would enforce it: They'd escort them into the section of Tartarus where they were going to see their eternal punishment begin, but according to Plato (via Theoi), they would also escort the not-good, not-bad people to a lake called Akheron. It was kind of like the Christian Purgatory — there the Furies would purify their sins and then finally let them move on.

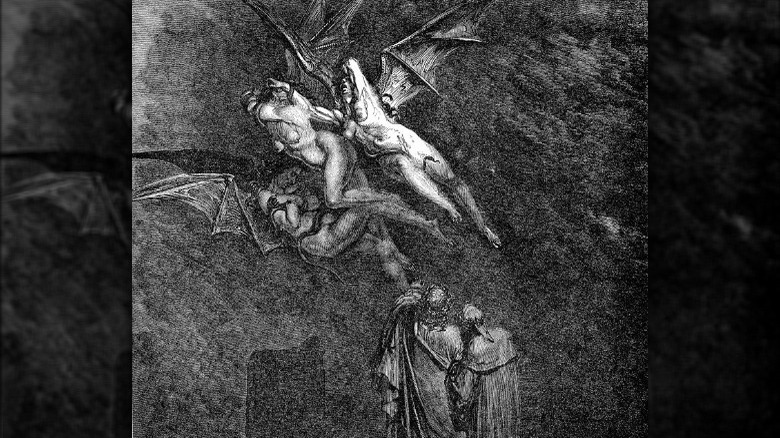

They weren't working alone

There were a lot of people doing a lot of terrible things, and it would have been a lot of justice-bringing for just three Furies. Fortunately, they had a whole slew of assistants and attendants who helped.

The harpies were storm spirits, creatures that were half woman and half bird. Sometimes depicted as beautiful blonde women and sometimes said to be terrible, monstrous creatures (as pictured), they were often associated with Zeus as his enforcers. But they were also said to do the bidding of the Furies: Homer wrote (via Theoi) that they were the ones that stole the orphaned daughters of Pandareus and gave them to the Furies as handmaidens, instead of allowing them to live the happy lives Aphrodite had wished for them. There were also a series of demigods and demons that were said to work alongside the Furies to torment mortal evil-doers. Ovid wrote that Tisiphone frequently traveled with the personifications of Grief, Terror, Mania, and Dread, while Quintus Smyrnaeus also gave a shout-out to the "nightmare-fiend of Mania."

They were also connected to a demonic spirit called Poine, who was said (via Theoi) to be the personification of everything the Furies loved: retribution and punishment. Sometimes, she's even described as their mother, and while the Furies concern themselves mostly with crimes against family members, Poine avenged other victims and punished those who had committed other crimes.

The Furies weren't concerned with free will, circumstances, or status

It's no secret that the Greek gods were fond of toying with mortal humans — just look at the mess that was the Trojan War. That came from three goddesses demanding some poor guy name one of them the most beautiful, and everyone knows that no good can come of that.

When it came time for the Furies to deliver their brand of justice, they really didn't care whether the offense had been carried out under a person's own free will, or if they'd been manipulated by the gods. Ovid wrote (via Theoi) of the unfortunate Myrrha, who was punished by the Furies for falling in love with her own father, in spite of the fact that Eros' interference was the only reason she did. (She was later turned into a tree and gave birth to Adonis, says RCT.)

Commit a crime by accident? It didn't matter to the Furies: When the Amazonian Penthesileia killed her sister in a hunting accident, she was haunted by the Furies for the rest of her life. A god yourself? That, too, didn't matter. During the Trojan War, Zeus took the side of the Greeks, while some of the other gods — including his brother, Poseidon — threw in with the Trojans. When he did, Homer wrote that Poseidon was warned he was risking the wrath of the Furies, who favored parents and older siblings.

The Furies maintained the natural balance of the world

Homer's "Iliad" is one of those timeless tales, and even though the story of the Trojan War has been told, and told, and told again, there's something that keeps everyone coming back. Buried in the story is a detail that's as fascinating as it is small, and according to Theoi, it suggests that the Furies weren't just delivering vengeance, they were also maintaining the natural order of things.

And given how much the gods like to interfere with things and muck up human lives, that might be a good thing.

The moment they're talking about comes when Achilles hitches his war horses — divine gifts given to his parents by Poseidon — to his chariot, getting ready to head into battle. Before he can, one begins to speak after being given the ability by Hera. Xanthos tells him that while he won't die in this battle, he warns "yet still for you there is destiny to be killed in force by a god and a mortal." Achilles asks the horse why the heck he's giving death prophecies, but the oddity had already caught the attention of the Furies, who took away Hera's gift. Not only were they keeping things as they should be, they were showing that even Hera, queen of the gods, wasn't out of their reach.

Summoning them was considered necromancy

There was really no telling how the Furies would be called down on someone. Sometimes, they witnessed a crime in person: Apollonius Rhodius wrote (via Theoi) that they were there when Jason and Medea killed her brother, Apsyrtos, and "took quick note of the heinous deed."

Sometimes, they were summoned by those who were wronged. Jason's father, Aeson, summoned one of the Furies even as his half-brother was forcing him to commit suicide, and in this case — and in others — summoning them was considered dabbling in necromancy.

Statius actually describes the typical summoning ritual (via Theoi), and it's just as dark as can be expected. Black sheep and cattle were brought together, and after the spilling of wine, milk, and honey, three fires were lit and the animals were sacrificed. Their blood was collected, and it — along with "half-dead tissues and yet living entrails" — were offered to the Furies, who would be summoned from the depths of hell by the ceremony. Valerius Flaccus wrote about how the whole thing ended: "The chief of the Furiai stood close by him, and touched with heavy hand the cup that steamed with deadly venom; eagerly they drank and drained the blood from the bowl."

The cult of the Furies

The Furies may have been depicted as merciless, ultra-violent, and capable of delivering the sort of vengeance that's permanent, but anyone who earned their wrathful attention absolutely had it coming. It makes sense, then, that they were also known as the Semnai — or, "the honorable" — and also as the Euminedes ("the kindly"). According to the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, since they only targeted those who were guilty of some pretty horrible crimes, they came to be seen as sort of a divine law enforcement that didn't just punish, but protected.

And that led to the development of their own cult, based in Athens at a place called the Areopagus. There, they were connected to Demeter, goddess of the grain and mother of Persephone, queen of the underworld, and were worshipped alongside her in shrines dedicated to both. Pigs, black sheep, and fresh water were among the common sacrifices presented to the Furies; In Thebes, they were worshipped — again, alongside Demeter and Persephone — at a sacred grove, where baby pigs were sacrificed.

Interestingly, they were also connected to oath-swearing. "Women citizens' festivals, debates and justice on the Areopagus" says that when legal proceedings required the swearing of an oath, it was often done at the altar of the Furies, before representatives wearing purple — the traditional color of the Furies — and called the Semnai Theai.

The Furies and their connection to mental illness

While it's hard to look at ancient civilizations through the lens of the knowledge we have now, scholars believe that the Furies were, in some way, a sort of explanation for some instances of mental illness.

History professor and head of the Center for the Ancient Mediterranean at Columbia University William V. Harris says (via The Atlantic) that "... in a world where many important phenomena such as mental illness were not readily explicable, the whims of the gods were the fallback explanation." He specifically cites the story of Orestes, who earned the wrath of the Furies after killing his mother to avenge his father. According to Aeschylus's play "Libation Bearers," (via Theoi), Orestes begins to see black-clad, snake-wearing demons he calls "the hounds of wrath" following him, along with the ghost of his mother. Other sources speak of his "madness" and his "insanity," and scholars today see the wrath of gods — particularly the Furies — as being an explanation for mental illness.

This existed alongside the idea that the mentally ill were just that — ill. While doctors began developing the idea that these people were sick and needed to be cared for, those who weren't medical professionals continued to blame the divine. Strangely, Harris adds that this explanation resulted in mental illness carrying less of a stigma than it does in the modern world, and that's food for thought.