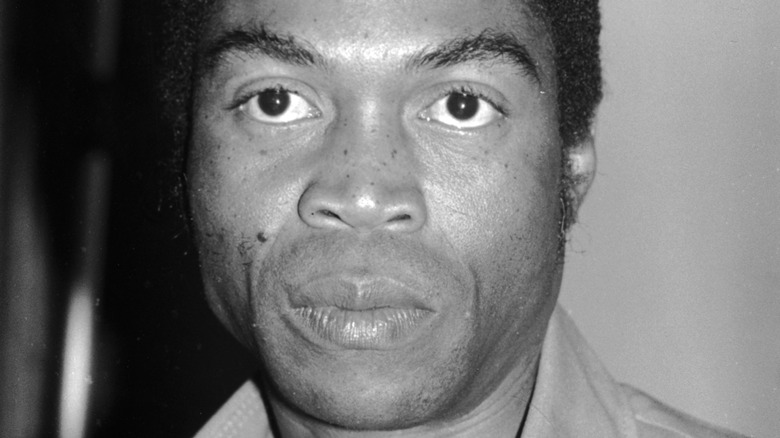

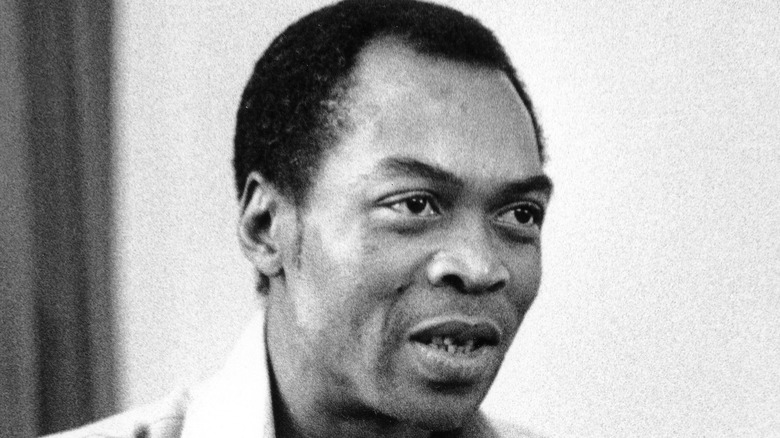

The Untold Truth Of Afrobeat Icon Fela Kuti

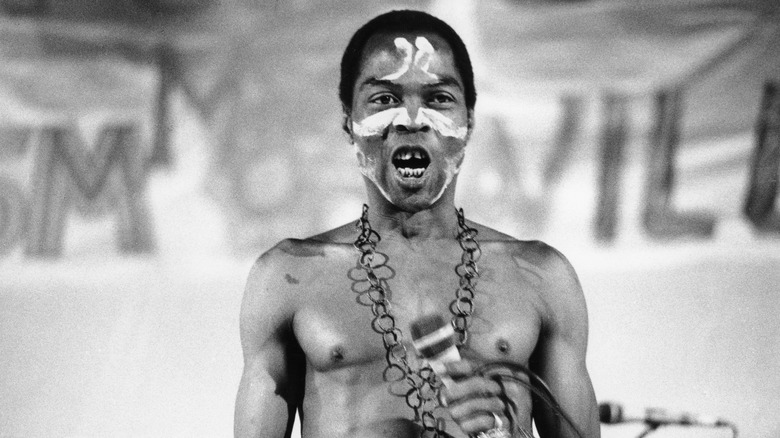

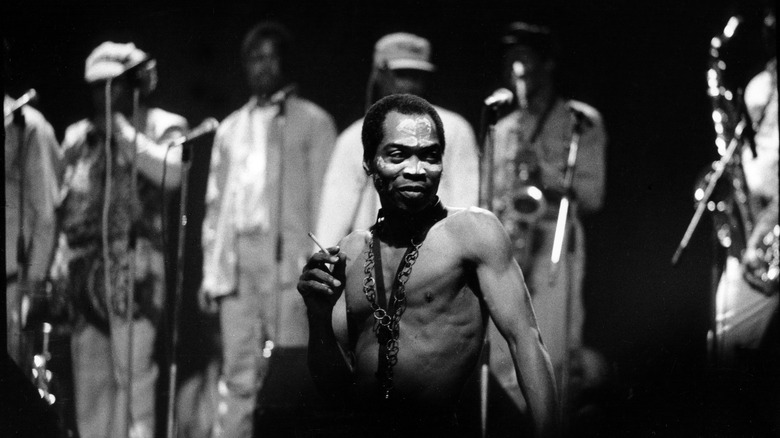

"Music is the weapon," stated the Nigerian musical superstar Fela Kuti in a 1982 documentary of the same name (via Kino Lorber). The remark has since come to be the singer's definitive statement, concisely encapsulating the late multi-instrumentalist's belief that music is one of society's most effective tools against colonial oppression and political corruption.

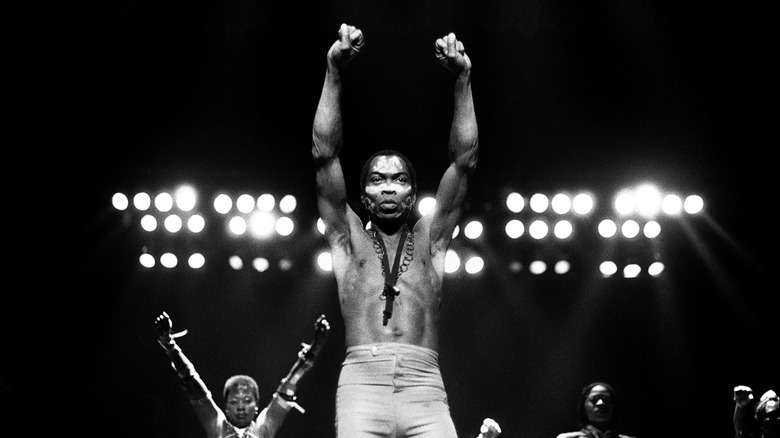

To his many fans, Fela Kuti is the ultimate protest singer, whose music is as much a call to resistance as it is a call to move your body to its infectious polyrhythms. But while his reputation rests predominantly on his innovative music — a genre of his own making, which he termed "afrobeat" — the life of Fela Kuti was similarly singular, lived according to his principles that held personal freedom and political expression as inalienable rights.

Kuti was "a tornado of a man who liked to play, eat, have sex, and get high," his manager, Rikki Stein, told The Guardian. "But he was also sweet – he loved humanity, he was principled. He was a lot of fun to be around. He'd show up in the lobby of a five-star hotel wearing nothing but a pair of Speedos." Here is the untold truth of one of the twentieth century's biggest and most complicated figures.

Fela Kuti's formidable family

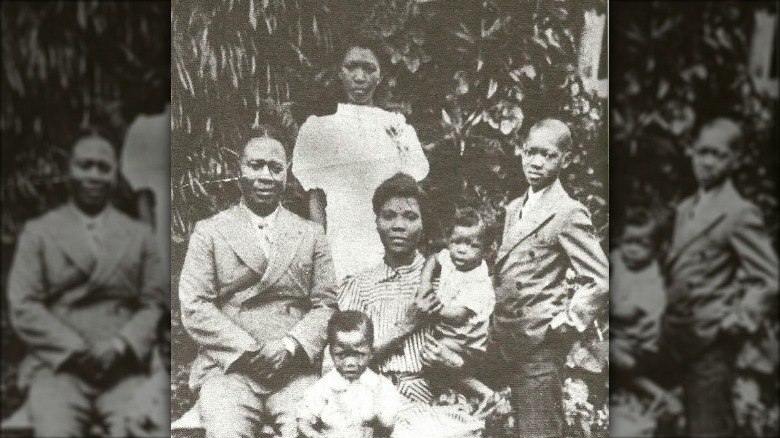

The man who would eventually crown himself the "Black President" didn't magic his forthrightness from nowhere. In fact, Fela Kuti came from a distinguished Nigerian family — The Guardian reports that they have been described as the "Kennedys of Nigeria" – whose wealth, connections, and political activism would ensure that the future musician would be well placed to become one of Nigeria's most famous sons.

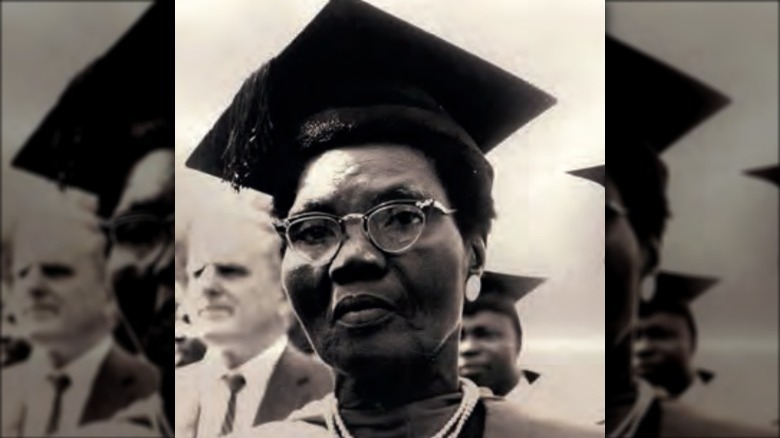

Kuti was born north of the Nigerian capital of Lagos in Abeokuta. His father, Reverend Israel Oludotun Ransome-Kuti, was a famous preacher and union leader, while his mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, was a renowned political activist and feminist pioneer, according to the Zaccheus Onumba Dibiaezue Memorial Libraries. After graduating as a teacher in the early 1920s, Funmilayo championed causes providing literacy for Nigerian women, and continued to fight for women's rights throughout her life; in 1949, her stewarding of protests against taxation on women and the ongoing denial of suffrage led to the Alake of Egbaland, Oba Ademola II, abdicating his throne, per the same source.

According to Al Jazeera, Funmilayo came to be known as the "lioness of Libani" — undoubtedly, it was through her that Fela inherited his strength of will and rebelliousness that would come to define his entire life.

A classical education

As well as being successful and politically active, Fela Kuti's family were wealthy; indeed, numerous sources such as The Guardian describe the family as being upper middle class, or, indeed, Nigerian aristocracy. And undoubtedly, the privilege Kuti's family enjoyed meant that he was well placed to seek out world-class training to realize his musical ambitions.

According to The Guardian, Kuti was expected to begin a career in medicine, following in the footsteps of his older brothers. His monied family paid for him to travel to London to receive a quality education, but rather than choose the medical path, Kuti chose to enroll at the Trinity College school of music (per All Music), where he studied piano and classical composition.

It was in London that Kuti started his first group, Koola Lobitos, which became well known on the London music scene in the early 1960s, though The Guardian notes that at the time Kuti had yet to create the afrobeat genre, and plied his trade playing highlife and jazz for London's cosmopolitan audiences while sharpening his compositional and playing skills; years down the line, Kuti would describe his innovative music fusing influences from both Africa and the West as "African classical music."

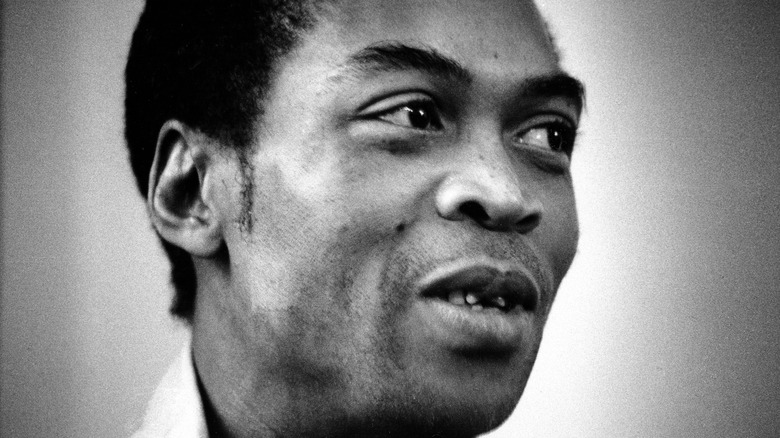

Fela's musical and political growth

Apart from Fela Kuti's classical training at Trinity College, London was a musical melting pot that provided a platform for Kuti to explore Western music trends and incorporate them into his own compositions, a habit that he would maintain for the rest of his life and which would make his music such an international success. Similarly, the British Library notes that several prominent African American artists such as Otis Redding and James Brown toured West Africa, meaning the West continued to influence Kuti on his return. But the West also offered a political awakening for Kuti, who while away from his own country was able to see Nigerian society, and Africa more generally, in sharp focus for the first time.

While on tour in the U.S. in the late 1960s, Kuti and his band made the acquaintance of numerous leading lights of the Black Panther movement, and began a relationship with one of their most prominent female members, Sandra Izsadore, who directed the musician to engage more directly with Black radicalism and post-colonial literature, according to the NME.

In an interview from the 1980s (via The Guardian), Kuti explained how he was only awoken to the colonial oppression of Nigeria belatedly: "Being African didn't mean anything to me until later in my life ... When I was young we weren't even allowed to speak our own languages in school. They called it 'vernacular,' as if only English was the real tongue." Thereafter, his songs became increasingly political, with lyrics reminding Nigerian listeners to embrace their native culture over that imposed upon them by the West.

A pan-Nigerian popularity

But though Fela Kuti rejected much of Western culture — most notably Western clothing, which, in his song "Gentleman," he tells his listeners will make Nigerians sweat and "smell like s***" (via The Guardian) — the language he predominantly sang in on his records and during shows was Nigerian Pidgin English — a creole-based language that first emerged between Nigerians and Portuguese traders, according to the Terminology Coordination Unit of the European Parliament.

The same source claims that Pidgin is considered a "bastardized" version of English because it is rarely used as a written language, but Pidgin was an important tool for Kuti — who was also fluent in the Southern language of Yoruba — as it was a way of communicating with as many listeners as possible. As the British Library notes, Nigeria is a land of over 500 languages, and while Pidgin English may be a product of colonialism, its use as a lingua franca among all classes of Nigerians meant a musician as politically aware as Kuti realized that the language was necessary to create a mass audience that might, together, affect real political change. In this way, his message traveled past the borders of Nigeria, to the rest of Africa and out into the world.

Fela Kuti's feud with the Federation of Nigeria

Fela Kuti once claimed: "If rascality is going to get us what we want, we will use it; because we are dealing with corrupt people, we have to be rascally with them" (via Biography).

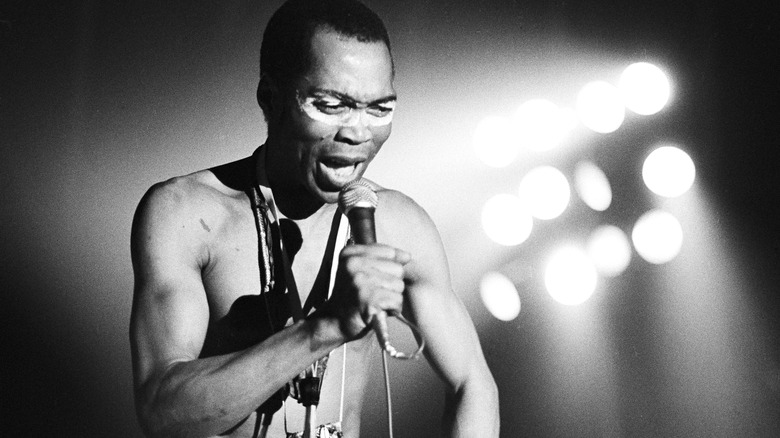

"His songs denounc[e] corruption, multinational corporations, police brutality, and 'V.I.P.-ism,'" read a 1986 profile of Kuti printed in The New York Times. By the time the profile was printed, Kuti had been one of the most vocal critics of the Nigerian hegemony for more than a decade and a half. Following his political awakening in the U.S., Kuti returned to Nigeria and placed political messaging at the heart of his newly renamed band, Afrika 70, and he soon became an undeniable political force in Nigeria, with songs unerringly criticizing the illegalization of drug use and brutal police raids being carried out across the country (per the Red Bull Music Academy).

According to Ventures Africa, Kuti's activism was also enacted outside the world of music. Throughout the 1970s and beyond he regularly bought space in national newspapers to broadcast his message of resistance against Nigeria's corrupt government, reminding Nigerians to stand up for the rights that were for so long denied to them.

The debate about Fela Kuti's sexual politics

But despite receiving the influence of one of Africa's greatest feminist icons in the form of his mother Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, Fela Kuti — as progressive and thoughtful as he was on so many other issues — cut a muddled figure when it came to the issue of women's rights and the promotion of feminism in Nigeria and beyond ... or, at least, from a Western perspective.

In 1973, Kuti released the epically long song "Lady" as the second side of his album "Shakala" — that Red Bull Music Academy states is the album on which Kuti first masters the sound of afrobeat – the lyrics of which read: "If you call am woman/ African woman no go gree/ She go say, she go say, I be lady o." (American English: "If you call her a woman an African woman will not listen/ She will tell you she is a lady," per MsAfropolitan.)

Academics such as MsAfropolitan have noted that Kuti errs towards promoting traditional values in his sexual politics, while at the same time highlighting Nigerian women's new sense of self-determination. As such, while his songs may simply be described as problematic from a feminist perspective, they do successfully encapsulate the debate around gender roles that was raging in Nigeria at the time, while Kuti's own polyamory — which we shall come to later — further complicates how his sexual politics are viewed today.

The foundation of the Kalakuta Republic

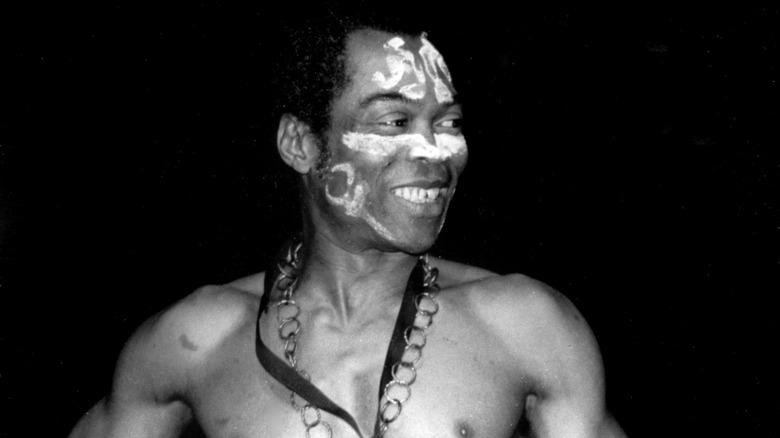

Tired of what he saw as an oppressive Nigerian society, in 1970 Fela Kuti founded in Lagos a communal compound that according to De Facto came to serve as a "secessionist state within Nigeria" housing Kuti's extended family, friends, bandmates, and sympathizers, allowing them freedoms that the government continued to withhold from everyday Nigerians at the time.

Within the compound, Kuti and his circle enjoyed sexual freedoms and the open use of marijuana that was illegal in wide Nigerian society, while a recording studio and concert venue allowed Kuti and Afrika 70 to develop and perfect the afrobeat sound. According to Ventures Africa, the compound was also notable for containing a free healthcare clinic, a facility usually reserved for Nigeria's elite.

Kuti later named it the Kalakuta Republic, the nickname of a jail cell in Alagbon Close where Kuti was imprisoned on suspicion of possessing marijuana in 1974, according to Pulse.

The murder of Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti

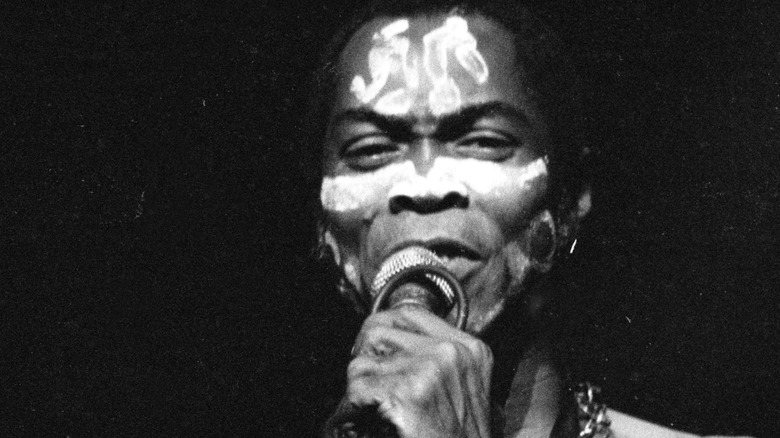

While Fela Kuti and his associates enjoyed the freedoms of the Kalakuta Republic, the singer continued his demonstrations of defiance against whoever occupied the seat of power in Nigeria. As reported in The Guardian, in 1977 Kuti released one of his all-time great protest anthems: "Zombie," a critique of the mindlessness of the soldiers representing the military junta of General Obasanjo who harassed Kuti constantly.

The same source claims that it may have been "Zombie" which led to a violent crackdown on the Kalakuta Republic compound that would ultimately take the life of Kuti's mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti. On February 18 of that year, the compound was raided by over 1,000 armed soldiers who violently assaulted Kalakuta's inhabitants, according to Pulse. In the process of the raid, the soldiers hurled Funmilayo from a second story window, after which she fell into a coma, never to recover. The Kalakuta Republic was burned to the ground.

Following his mother's death, Kuti brought a coffin — purportedly containing his mother's body — to the gates of the barracks housing Obasanjo and many of his troops, though they refused to receive the incriminating offering (per Treble Magazine). Kuti broadcast the tragedy he had suffered and his ongoing defiance on the 1981 track "Coffin for Head of State."

Fela Kuti's polygamous marriages

Outside of his music, one of the most notorious aspects of Fela Kuti's life was his polyamory — specifically, his simultaneous marriage to 27 women on a single day. But as the academic Derek Stanovsky points out (via NC State University), to see Kuti's polygyny as an extension of the misogynistic tendencies of some of his lyrics would be a mistake, as would attempting to label the marriages a remnant of traditional tribal practice in an otherwise progressive — by Western standards — life. In fact, decades on, Kuti's own children struggle to understand their father's motivation, though several explanations exist.

According to Old Naija, the marriages, which were blessed by 12 priests, occurred in Lagos on February 20, 1978, almost exactly a year after the razing of the Kalakuta Republic. The same source argues that the marriages were intended as a way of keeping the group — who had previously lived in the compound and comprised a good portion of Kuti's bandmates — together, while The Guardian claims that Kuti had argued that the marriages prevented the women being stigmatized as sex workers.

However, as noted by The Guardian, the marriages did not last; Kuti divorced his wives in 1986, rejecting marriage as an institution that commodifies women's bodies.

The Movement of the People

In 1979, Fela Kuti formed a political group named Movement of the People (MOP), which, he explained, would "clean up [Nigerian] society like a mop." (via The Wire) Through the group, Kuti announced that he would run for the Nigerian presidency in the forthcoming democratic elections, the first since the military coup of 1966. Songs such as "M.O.P. (Movement Of The People) Political Statement Number 1" and the 1981 album "Black President" telegraphed Kuti's burgeoning ambitions. However, Kuti's candidacy was rejected by the Federal Electoral Commission.

Kuti was hurt by his failure to enter office, and decried Nigeria's elections as the imposition of an invasive form of European democracy. Performing at Britain's Glastonbury Festival in 1984, Kuti told the audience: "We all know that Europeans taught Africans what we know today, what we use for our governmental processes. We all know about democracy. I condemn democracy now" (via YouTube).

Fela Kuti's unjust imprisonment

Fela Kuti's rebelliousness meant that he spent spells in prison throughout his life, though one jail term is especially notable. In 1984, Nigeria found itself once again under the rule of a military government, this time headed by the Army Major General Muhammadu Buhari. By now, Kuti had abandoned his ambition to enter political office, but as always he remained a vocal critic of the Nigerian government.

Kuti was returning from Nigeria from a tour of the U.S. when he was detained for what officials claimed was the illegal trafficking of foreign currency, though, as The Guardian points out, Kuti and his entourage insisted that the American dollars were correctly declared. The musician was sentenced to five years in prison, which he and his supporters claimed was an attempt to silence him. The New York Times reported that Kuti was declared a "prisoner of conscience" by Amnesty International. Kuti was released after 20 months following a change of military government, and received an apology from the judge who had sentenced him. Per The New York Times, 2,000 fans and well-wishers were there to greet Kuti upon his release.

Kuti later claimed that his extensive prison spell had taught him patience and allowed him to master existing in a meditative state: "Prison didn't change my life, it developed my way of thinking. I am very spiritually inclined. I am in prison, it gave me a lot of time to meditate and think about what this world is really about. It [gave] me knowledge about time. If anybody tells me 20 years is a long time, I will tell him no because prison has taught me that time is meaningless unless you want to understand what time is all about" (via The Cable).

Fela Kuti's HIV denialism

Following his release, Fela Kuti continued to tour and record, and remained a loud voice within political discourse around Nigeria and Africa in general. But as the 1980s became the 1990s, there was one crisis faced by Africa and the wider world that Fela would struggle to come to terms with: the growing AIDS epidemic.

As described by the Village Voice, Nigeria's response to HIV — the virus that causes AIDS — was coordinated by Fela's bother, Professor Olikoye Ransome-Kuti, who was the country's health minister. But while the medical side of the family were facing the reality of this new threat, Fela remained staunch in his denial that it even existed. The problem was compounded by the musician's simultaneous opposition to condom use, which, per the same source, he believed to be a plot to reduce Africa's Black population. Similarly, Olikoye claimed: "[Fela believed] all doctors were fabricating AIDS, including myself."

"You have to understand the effect of colonialism on people like my father," Fela's son, Femi, explains. "If Europe talks about AIDS or that AIDS is killing Africa, then people like him would have to fight back. There was not enough proof during my father's era that AIDS was caused by sex. I think the way AIDS was marketed — the propaganda against AIDS was not well put together by the UN" (via The World).

Fela Kuti's tragic death

As The Guardian notes, the final song recorded in Fela Kuti's lifetime, "Condom Scallywag and Scatter," gave some indication of his unwavering opposition to the growing consensus during the HIV/AIDS pandemic for the need to practice safe sex. But Kuti, who in a 1981 interview with OOR Music Magazine claimed that "on average I sleep with two or three women a day" (via Afrobeat Music), would tragically come to be among the epidemic's victims.

Despite his family's medical leanings, Kuti preferred to employ traditional African herbalist remedies to cure his ailments, according to the Village Voice. As such, it was too late to save the musician when he was eventually taken to the hospital, and he died of complications of AIDS on August 7, 1997. He was 58.

Kuti's death rocked Nigeria and has been credited as raising awareness of the reality of the disease that killed him. According to Al Jazeera, more than one million people attended his funeral in Lagos Island's Tafawa Balewa Square.

The Kuti name goes on

More than two decades after his tragic death, the music of Fela Kuti continues to attract millions of listeners in both West Africa and the wider world, while Kuti remains a musical and political Nigerian icon. In his native country, he has paved the way for the next generation of politically minded artists, as his son Seun attests: "People here respect afrobeat artists because they know we are trying to give the people some kind of voice" (via The Guardian).

Kuti left behind a body of work totaling more than 50 albums, while his reputation has been solidified by the continuation of the afrobeat tradition by his daughter, Yemi, and sons Femi and Seun, who tour the world extensively playing their father's music (all three began their careers as members of Kuti's band, Egypt 80, per felakuti.com).

And while afrobeat as a genre remains in rude health, the story of Fela Kuti and his importance as a world figure has been brought to new audiences by documentaries, biographies, and even an off-Broadway hit musical, "Fela!," first performed in 2008.

The revival of the Movement of the People

In January 2021, The Guardian published an interview with Fela Kuti's son, Seun (pictured), in which the musician described his desire to carry on his father's political legacy in the same way that he and his siblings Femi and Yemi continue to carry the torch for his music. "For 60 years nothing has really been solved in this country," Seun claimed. "Healthcare, education, electricity, transportation, welfare – nothing has been accomplished."

Facing the challenges of police brutality just as his father did in the 1970s and 1980s, Seun has announced the resurrection of Fela Kuti's Movement of the People party, which he believes can today enjoy more cut-through in an age when media is more widely available and the problems that Nigeria faces are more easily documented and shared. "Today it will be easier for such a message to reach the core of Nigerian people than it was in the 70s. The problems are so glaring," he told The Guardian, adding that MOP was "giving the masses a voice and building class consciousness."