The Untold Truth Of Karl Marx

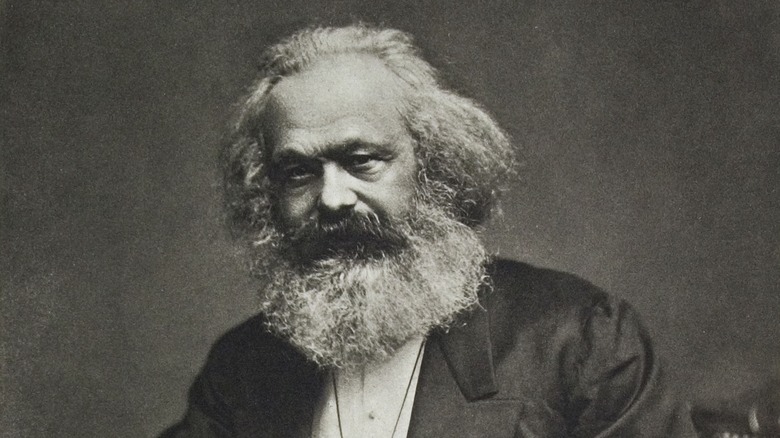

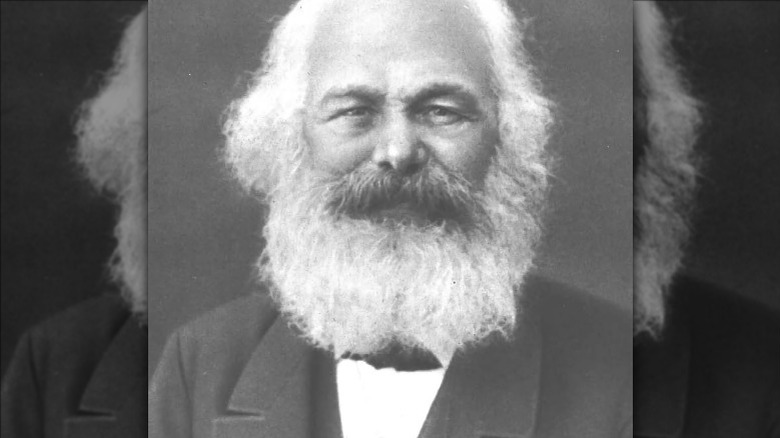

Karl Marx exists as more a symbol than as a person. He is so closely tied with communism, with a version of the political and economic ideology even named after him, that nothing else about him seems to matter. People know that Marx had a big beard and that his writings "The Communist Manifesto" and "Das Kapital" have led to revolutions and millions of deaths around the world.

But regardless of how you feel about communism, or if you have never read his work, you can absolutely agree that Marx as a person was an intriguing, quirky mess. He was a genius who rarely changed his underwear and drank way too much, yet had a seemingly perfect marriage (almost) and was a great father to his kids (the few who lived, anyway.) He was obsessed with Shakespeare, wrote endless letters to his friends and loved ones, and was a gifted storyteller. In other words, he was a real, flawed, and fascinating human, above and beyond the socialist movement his works codified.

This is the untold truth of Karl Marx.

He participated in a duel

In his youth, Karl Marx was a bit of a bad boy. Once the brilliant young man went off to college, you'd expect him to study hard. But he might have been too smart, since he could study and still find time for causing trouble. According to "Karl Marx: A Life" (excerpted in the New York Times), he became co-president of the Trier Tavern Club, which was basically a couple dozen guys who liked to get drunk and violent. Marx found himself in regular pub fights and scrapes with the law.

But it escalated when a member of rival gang the Borussia Korps challenged Marx to a duel, and he accepted. Considering Marx was shortsighted, and the challenger was a soldier, it could have ended much worse than it did. Fortunately, Marx was only grazed by his rival's bullet. His father was not impressed and pointed out this wasn't exactly what college was about. "Is dueling then so closely interwoven with philosophy?" his father asked in a letter. "Do not let this inclination, and if not inclination, this craze, take root. You could in the end deprive yourself and your parents of the finest hopes that life offers."

Marx might have learned his lesson, because, according to "Love and Capital: Karl and Jenny Marx and the Birth of a Revolution," years later when he was again challenged to a duel, this time by a fellow communist who thought Marx wasn't radical enough (seriously), he laughed it off and never considered accepting.

He liked his booze

It's impossible to diagnose someone from the past, but Karl Marx definitely showed signs he had an alcohol abuse problem. It started out when he was young. When he was leaving home to start college, his mother wrote him a letter telling all the things he should not do, according to "Karl Marx: A Life" (excerpted in the New York Times): "You must avoid everything that could make things worse, you must not get overheated, not drink a lot of wine or coffee, and not eat anything pungent, a lot of pepper or other spices. You must not smoke any tobacco, not stay up too long in the evening, and rise early." It's safe to say Marx treated this more as a to-do list.

His "Certificate of Release" (basically a report card) after his first year at Bonn University noted that he was a fabulous student, exhibiting "excellent diligence and attention," but there were ... some issues. The report continued: "He has incurred a punishment of one day's detention for disturbing the peace by rowdiness and drunkenness at night ... Subsequently, he was accused of having carried prohibited weapons in Cologne. The investigation is still pending." Marx was eventually spared jail, but his carousing carried on.

The drinking continued into adulthood. "The Big Three in Economics: Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and John Maynard Keynes," notes that a spy from the Prussian police visited Marx in London and sent back a report saying that the radical "gets drunk readily."

Karl Marx had a complicated relationship with his father

Karl Marx had a difficult relationship with his father. According to an excerpt from "Karl Marx: A Life" (via the New York Times), Heinrich Marx looked out for his son, even to the point of telling him how to get out of military service, saying young Karl should find a physician who would exaggerate how bad his lungs were and to not feel bad about lying. When Karl was found with an illegal weapon on him during university, Heinrich wrote to the judge, begging for his son to be let off.

But their relationship fractured over the years. In one letter, Heinrich showed he knew his opinion meant nothing to his son, "I can only propose, advise. You have outgrown me," and in another complained about how little Karl seemed to care about his loved ones: "While still so young, you became estranged from your family." Other complaints, all from one bitter letter sent near the end of Heinrich's life, included the fact that Karl hardly ever replied to his parents' letters, never asked about their health, that he spent way too much money, didn't talk to his siblings, and married too young. When Heinrich died the next year, Karl did not bother attending his funeral.

Despite it all, Karl obviously adored his father. He dedicated a small book of poems to "my dear father on the occasion of his birthday as a feeble token of everlasting love." And when Karl Marx died, he had a picture of his father in his pocket.

Karl Marx's controversial marriage to Jenny von Westphalen

Karl Marx married up, even though "Love and Capital" records that a resident of Marx's hometown of Trier once said that he was "nearly the most unattractive man on whom sun ever shown." Jenny von Westphalen was four years older, from an aristocratic background, and engaged to someone else. (She was also a looker, described by locals as "most beautiful girl in Trier" and the "queen of the ball.") All of this meant, at the time, her marriage to Marx would be a scandal.

Even Marx's father Heinrich though Jenny was making a huge mistake, writing to his 19-year-old son that she was "a girl who has made a great sacrifice in view of her outstanding merits and her social position in abandoning her brilliant situation and prospects for an uncertain and duller future and chaining herself to the fate of a younger man." But love prevailed, and they wed in 1843 after a years-long engagement, per "Karl Marx: A Life" (excerpted in the New York Times).

Jenny was happy with, and even proud of Marx's revolutionary ideas and obvious genius. Before they married, she wrote him a letter saying she had a dream that he lost his right hand in a duel, "and Karl, I was in a state of rapture, of bliss, because of that ... I could write down all your dear, heavenly ideas and be really useful to you ... your dear words poured down on me and I listened to every one of them and carefully preserved them for other people."

He was poor -- or was he?

Many articles about Marx's life record that he was extremely poor. He was – for about a decade of his adult life. But even that poverty came with some very big buts.

The description of Marx's living situation during the first years after he and his family arrived in London does sound terrible. According to "The Big Three in Economics," a Prussian police spy wrote a report which noted that "Marx lives in one of the worst, and thus cheapest, quarters in London ... everything is broken, ragged and tattered; everything is covered with finger-thick dust; everywhere the greatest disorder ... But all this causes no embarrassment to Marx and his wife." And Marx himself had to beg money constantly from his patron Friedrich Engels. One letter explained, "I am unable to go out for want of the coats I have in pawn, and I can no longer eat meat for want of credit ... [I] cannot call the doctor because I have no money to buy medicine. For the past eight to 10 days I have been feeding my family solely on bread and potatoes ... If possible, therefore, send me a few pounds."

It definitely sounds like abject poverty. But "Capitalism and Classical Social Theory" explains that at the same time, Marx employed a private secretary, and considered regular vacations and private school for his daughters to be "necessities." He simply refused to get a job with a regular paycheck and spent beyond his means. During those terrible years of poverty, he still earned three times more than the average skilled worker. And by 1864, he was rolling in it, living off inherited money and stock speculation.

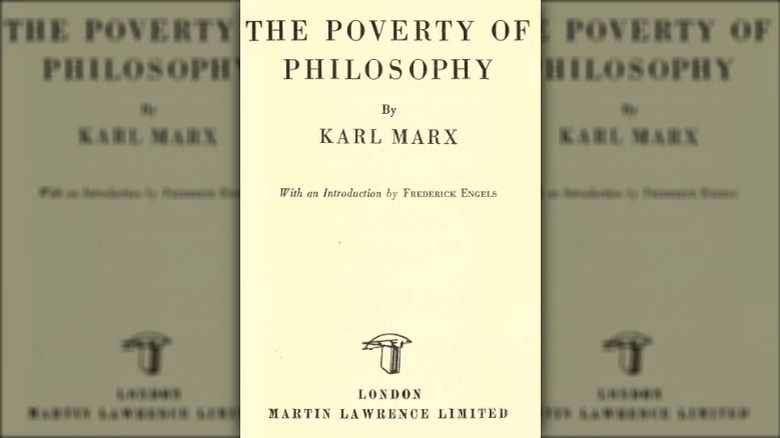

Karl Marx's other genres of writing

It was, perhaps, very lucky for Karl Marx that he was brilliant at economics, philosophy, and politics, because we have evidence of his more creative writing endeavors, and they are not good. In 1837, when he was 19, Marx started a novel. Called "Scorpion and Felix," only fragments survive today, but apparently Marx's attempt at satire was, to quote his biographer Francis Wheen (via the New York Times), "a nonsensical torrent of whimsy and persiflage." (Persiflage, as we all know, is a mocking sort of banter.)

That same year Marx tried his hand at poetry, resulting in a small book of verse. The opening lines of one poem, "Three Little Lights," are indicative of the quality of the rest of them: "Three distant lights gleam quietly/ They shine like starry eyes to see/ The storm may rage, the wind may shout/ The little lights are not blown out" (via Marxists.org). Yeesh.

Two years later, at the age of 21, Marx, having given up on his novel and poetry, must have thought his real talent was in combining the two and writing a play. The result was "Oulanem." As "The Big Three in Economics" points out, one soliloquy draws heavily from Hamlet's "to be or not to be" speech, starting with a the character's realization of mortality and ending, "The leaden world holds us fast and we are chained, shattered, empty, frightened, eternally chained to this marble block of Being, chained, eternally chained, eternally. And the worlds drag us with them on their rounds, howling their sounds of death. And we—We are the apes of a cold God."

His health issues

In 1967, just after the height of the Cold War, Time magazine ran an opinion piece about the 100th anniversary of the publication of the first volume of Karl Marx's "Das Kapital." Considering the U.S.'s feeling towards communism, seen as all Marx's fault, the piece is not kind about his work's legacy. But one interesting thing they note is that when writing his tome, Marx was in constant, terrible pain.

The list of his ailments is long: he suffered from an "enlarged liver, hemorrhoids, recurrent eye infections, insomnia, and boils." The boils, in particular, were horrible. Marx often wrote about them in his letters, calling them "curs" and "swine." Reuters explained they were "chronic" and "excruciating." In 2007, Sam Shuster, professor of dermatology at the University of East Anglia, thought he figured out the cause: hidradenitis suppurativa. This is when certain sweat glands, especially in the groin and armpits, get blocked, leading to swelling, and sometimes wider infection. Shuster published a paper on his theory. "In addition to reducing his ability to work, which contributed to his depressing poverty, hidradenitis greatly reduced his self-esteem," Shuster said. "This explains his self-loathing and alienation, a response reflected by the alienation Marx developed in his writing."

While Marx might not have thought his entire political and economic philosophy was down to the fact he couldn't sit comfortably a lot of the time, he was aware enough to know his painful situation had some sort of effect. In 1867, the year the first volume of "Das Kapital" was published, Marx wrote to Friedrich Engels, saying, "The bourgeoisie will remember my carbuncles [boils] until their dying day."

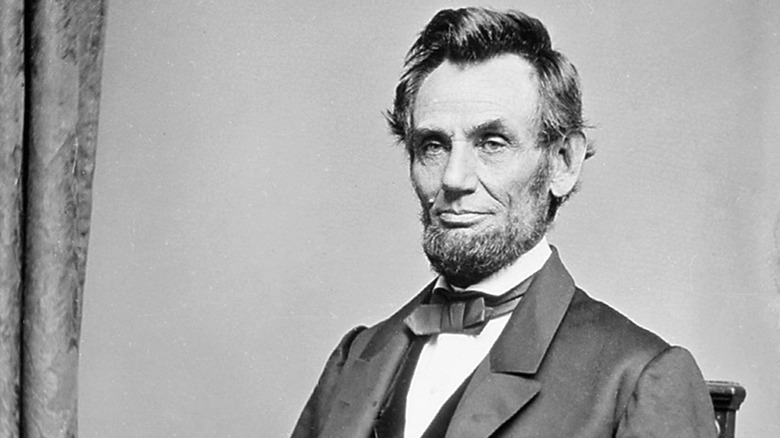

Karl Marx's relationship with Lincoln

This is one of those weird combinations of people you never think about being alive at the same time, let alone interacting. It's seemingly very different worlds colliding, but it turns out that Abraham Lincoln was a huge fan of Karl Marx, and that respect was returned in kind. The two shared mutual friends, and according to no less a figure than Martin Luther King Jr. (via the Washington Post), "Abraham Lincoln warmly welcomed the support of Karl Marx during the Civil War and corresponded with him freely."

It's not as weird as it first seems. John Nichols, author of the book "The 'S' Word: A Short History of an American Tradition ... Socialism," explains that "It is indisputable that the Republican Party had at its founding a red streak." For the time, it was a party with an incredibly radical platform. Lincoln even wrote in an official letter to Congress (which eventually became the State of the Union speech), something that sounds overtly socialist: "Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration."

When Lincoln was reelected in 1864, Marx wrote him on behalf of the International Workingmen's Association, saying they "congratulate the American people upon your reelection ... the workingmen of Europe feel sure that, as the American War of Independence initiated a new era of ascendancy for the middle class, so the American Antislavery War will do for the working class."

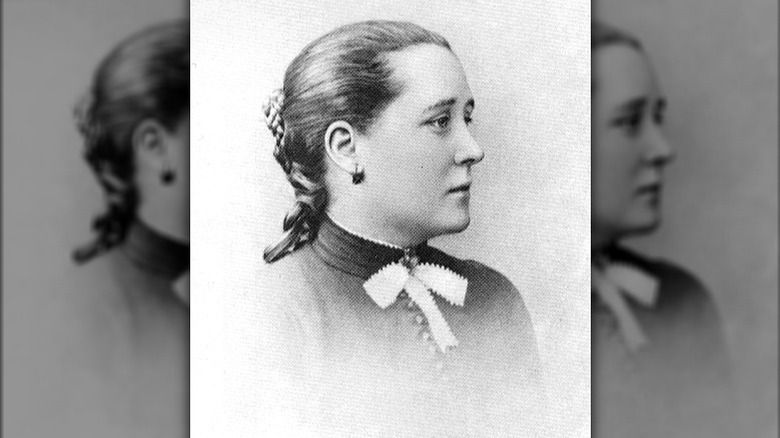

Karl Marx had an illegitimate child

While Karl Marx seemed to be deeply in love with his wife, he also betrayed her in the most awful way possible. He had an affair and fathered a child. And it just gets worse from there.

The mother, named Helen Demuth (pictured), lived in the Marx household as an unpaid maid and companion of Jenny Marx, according to "The Big Three of Economics." So Karl was her boss, assumedly the only home she had if she did not get a salary, and close to his wife. It also brings up the question of consent. In 1851, eight years after Jenny and Karl married, Helen gave birth to his son. Karl was terrified that if Jenny found out, it could kill her, or that their marriage would be over. So the New York Times says he made a second mistake and ruined his son Fredrick "Freddy" Demuth's life.

Friedrich Engels agreed to imply he was Freddy's father, and the child was given to a working-class family to raise. Freddy was a "neglected, lonely child" (via Love and Capital). He received only small, occasionally handouts from Engels and nothing from Marx. Engels rarely visited him, and Marx never did. Freddy received very little education and worked as a laborer. He would eventually die poor and alone in London at 78, still not knowing who his father was.

Engels and Marx did a meticulous job hiding Freddy's real paternity. On his deathbed, after Marx had passed, Engels told one of Marx's daughters the truth, but it wasn't public knowledge until a biography published in 1962.

He shaved off his beard

Karl Marx is immediately recognizable because of his big bushy beard. Drawings and paintings of him as a young man show a less hirsute figure, but by the time he was being photographed, the beard was firmly a part of him.

According to "The Big Three in Economics," Marx was gifted a massive statue of Zeus in the 1860s and decided that was his look. While he already had quite the beard, he decided to become even more Zeus-like. He stopped cutting his hair or trimming his beard altogether, so that for the last two decades of his life, his face was surrounded by an unruly hair halo.

So it's shocking to think that in his old age Marx actually shaved off his beard completely, all in one go. In 1882, he was in Algeria, and the beard became an issue. The Los Angeles Review of Books records that he wrote to Friedrich Engels back in England, explaining "because of the sun, I have done away with my prophet's beard and my crowning glory, but (because my daughters would rather have it this way) I had myself photographed before offering up my hair at the altar of an Algerian barber." You can imagine why his adult daughters wouldn't be a fan of him shaving, considering they had probably never seen him without a beard before. The image of Marx above is the photograph he's referencing in that letter, the last one taken of him with his beard, indeed, the last picture taken of him at all. He died a year later.

In the bust that sits atop his tombstone, the beard is back in place.

Karl Marx believed in phrenology

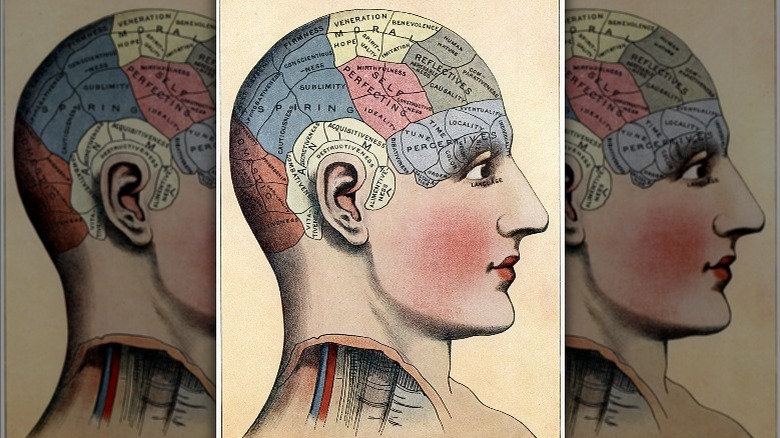

According to a paper in the "Proceedings of the XXIII World Congress of Philosophy," in the late 1700s, a German doctor named F.J. Gall invented the pseudoscience of phrenology. He thought there were "functional connections between psychic faculties, areas of the brain, and the shape of the skull."

You've probably seen those white decorative heads with maps like the one pictured covering the skull. We now know it's absolute nonsense, and it was often used for racist reasons, using different skull features to "prove" white people were the best and the smartest. Marxists in the 20th century, to their credit, called out phrenology as bunk. Which was especially weird considering Karl Marx himself believed in it, to the point that analyzing someone's skull and making judgments about them was something of a personality quirk, reports "The Big Three in Economics."

Wilhelm Liebknecht, a fan of Marx and believer in his ideology, remembered how when he first met his idol at a communist picnic (like you do), Marx "began at once to subject me to a ridged examination, looked straight into my eyes and inspected my head rather minutely." It wasn't just Liebknecht, as Marx "used the cranioscopic method to make a personal selection of the militants of the Communist League." While Marx seemed to like what he saw and became close with Liebknecht, he was all too happy to lean into the racist tropes phrenology was famous for, making copious and disturbing use of the n-word and slurs against Jewish people if he didn't like someone's head shape. (As Marx well knew, his family converted from Judaism for political reasons when he was a boy.)