What Really Happened During The Haymarket Affair

The Haymarket Affair, also known as the Haymarket Tragedy, is one of the darker chapters of labor history in the United States. Some claim that it set the eight-hour workday movement and the overall labor movement back, and before McCarthyism, it led to the original red scare.

ThoughtCo writes that the Haymarket Affair was used to discredit unions, and conservatives denounced anarchists by associating them with violence. Even when the Illinois governor noted that the trial had been recklessly unfair, his political career was damaged, and he was called a "friend of anarchists." In some ways, the disparagement of anarchists can be traced back to the Haymarket Affair.

But what exactly was the Haymarket Affair and why did it become such a big deal? And who was responsible? With tens of thousands of workers going on strike in the United States in 2021, it's worth looking back on one of the most pivotal moments in striking history. This is what really happened during the Haymarket Affair.

The May Day strike

By the end of the 19th century, some cities and states started passing laws that limited the number of hours in a legal workweek. But because there was still no federal regulation on the number of working hours per day, in 1884, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions passed a resolution. According to "Urban Revolt" by Eric L. Hirsch, the federation resolved that "eight hours shall constitute a legal day's labor from and after May 1, 1886" and decided that this would be achieved with a general strike.

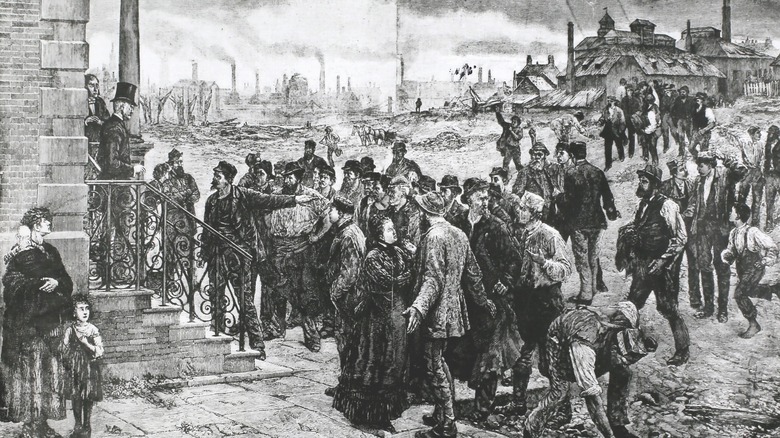

On May 1, 1886, labor organizers Lucy and Albert Parsons led thousands of workers in what would become the first May Day parade. According to Teen Vogue, the marchers chanted, "Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what we will!" while walking down Chicago's Michigan Avenue. Along with them, up to 350,000 workers struck across the nation, Ohio History Central reports.

Two days later, labor activist August Spies was preparing to give a speech at the McCormick Harvester factory, which had recently dismissed union activists and replaced hundreds of employees with the protection of Pinkerton agents. As Spies was about to begin his speech, the shift ended, and as the strikebreakers tried to leave, they were driven back into the plant by the workers at the meeting. Police arrived and pursued the strikers, killing one person and wounding up to six others, Hirsch writes.

Speeches at Haymarket Square

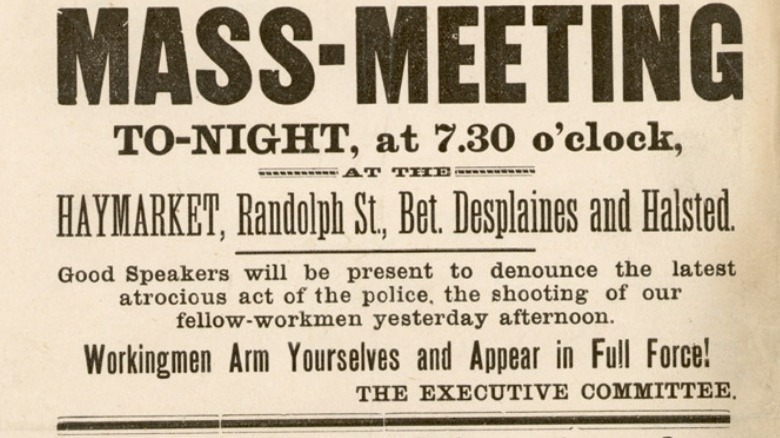

In response to the violence, August Spies organized another meeting for the following evening, May 4, in Haymarket Square. This time, the meeting was going to be a protest of police brutality, according to "Urban Revolt." The pro-labor union mayor of Chicago, Carter Harrison, gave permission for the meeting. And in addition to being in attendance that night, he "agreed that no police action was necessary."

Although the speeches were supposed to start at 7:30 p.m., most speakers didn't show up, and the meeting started an hour late. And instead of the expected 20,000, less than 2,500 people showed up, according to the Illinois Labor History Society. Because some speakers didn't show up, Albert Parsons and Samuel Fielden were brought over as replacement speakers. And as a dark cloud approached and it started to rain, many workers — including Lucy and Albert Parsons — left the meeting, leaving only around 200 people remaining. The meeting was nearly over, and Fielden was just finishing up his speech when around 175 police officers showed up.

The bombing of Haymarket

Carrying Winchester repeater rifles, the police officers ordered the crowd to disperse. And before much else could happen, a dynamite bomb exploded. The bomb went off near some of the police officers, killing one instantly and injuring several others. According to the Chicago Reader, some historians believe that this was the very first time that dynamite was used in the United States. As of 2021, no one knows who was responsible for the bomb.

Eric L. Hirsch writes that in response to the bombing, the Chicago police officers started firing everywhere indiscriminately. Four workers were killed as a result, and at least 20 were wounded. In addition, six police officers died, and countless more were injured by the reckless gunfire. Illinois Labor History Society writes that the United States declared martial law across the country the following day. In Chicago, leaders of the labor movement were arrested, and union newspapers were closed as police allegedly searched for the bomber. Hirsch describes it as America's first "red scare."

Despite countless raids and searches, the bomber was never found. But since Illinois state's attorney Julius S. Grinnell needed people to prosecute, the Chicago police started arresting anarchists associated with the labor movement, according to the Law Library.

The Haymarket trial

Samuel Fielden, Michael Schwab, and August Spies were arrested the day after the riot, and before long, George Engel, Adolph Fischer, Louis Lingg, Oscar Neebe, and Albert Parsons were arrested as well. And on May 27, 1886, they were all charged with murder and conspiracy to overthrow the United States political and economic system. The trial of Illinois vs. August Spies et al. began on June 21. The Law Library writes that Judge Joseph E. Gary was accused of influencing the jury panel, and it's worth noting that "since none of the jurors worked in a factory, they were not expected to be sympathetic to the union cause, which was really on trial."

According to "Urban Revolt," the media assigned a guilty verdict before the trial even started, calling the anarchists "vipers," "ungrateful hyenas," and "serpents" who "menaced the very foundations of American society." On August 20, the jury found all eight people guilty. Seven were given the death penalty, while Neebe was sentenced to 15 years imprisonment. Although the death sentence was appealed, the Illinois Supreme Court upheld the verdict on September 15, 1887. However, Fielden and Schwab's sentences were commuted to life in prison.

Executions and pardons

The day of the execution was set for November 11, 1887. George Engel, Adolph Fischer, Albert Parsons, Louis Lingg, and August Spies were all meant to be executed, but one day before, Lingg committed suicide in prison, per PBS. The day of the hanging, Engel, Fischer, Parsons, and Spies were all brought out to the hangman's platform with hoods covering their faces. Before being hung to death, Spies spoke out: "The day will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you are throttling today."

Fielden, Schwab, and Neebe remained in prison for seven years until the new governor of Illinois, John Peter Altgeld, pardoned them. The Chicago Tribune reports that when Altgeld reviewed the Haymarket affair, "he saw an appalling miscarriage of justice." The prosecutors had alleged that even if they didn't know who was responsible for the bomb, the eight anarchists were just as guilty due to their "inflammatory, sometimes violent anti-establishment rhetoric." In his 18,000-word pardon message, Altgeld wrote that such a manner of assigning guilt was unheard of in the United States "in all the centuries during which government has been maintained among men, and crime has been punished."