The Tragic Murder Of Allen R. Schindler Jr.

Many remember the U.S. military's policy on gay people as "Don't Ask, Don't Tell," but the full name of the policy actually included the idea "Don't Harass." This notion that, while gay people weren't explicitly allowed in the military, they shouldn't be subject to harassment came at the heels of a horrific murder in the U.S. Navy.

The 1992 murder of Allen R. Schindler Jr. is said to have instigated the "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" policy due to the compromise that was established after the ban on gays in the military was sought to be repealed. But what led to Schindler's murder? And what happened to the perpetrators?

The repeal of "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" was one of the final chapters in the legacy of Schindler's murder. While the ban against transgender people in the military was seen as a repeat of the "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" policy, the ban was overturned in January 2021. However, violence against non-heteronormative people continues in 2021. This is the tragic murder of Allen R. Schindler Jr.

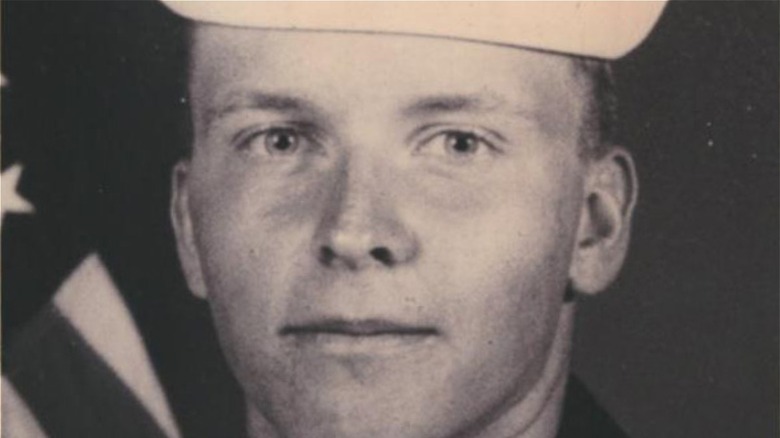

Who was Allen R. Schindler Jr.?

Allen R. Schindler Jr. was born on December 13, 1969 in Chicago Heights, Cook County, Illinois to Dorothy Hajdys-Clausen and Allen Schindler Sr. When Schindler was only one month old, his mother Dorothy got a job at John's Frozen Pizza to help pay the mortgage because Allen Sr. was unemployed. Two years later, she took on another job at Burger King, and her aunt Marie ended up raising Schindler throughout his childhood and taking care of him during Dorothy's divorce from Allen Sr, according to The New York Times.

When Schindler was 18 years old, he left his hometown for the very first time and joined the navy, according to Patch. In January 1991, Schindler was transferred onto the USS Midway, an aircraft carrier, where he worked as a radioman. Esquire writes that those "eleven months aboard the storied carrier were among his happiest days in the Navy."

But in December 1991, after the Midway was decommissioned, Schindler was transferred to another ship — the USS Belleau Wood, an amphibious assault ship — which had "a reputation for chaos and turmoil." And while on the Midway, Schindler had been able to speak "openly if discreetly about his sexuality," he encountered a much more intolerant and hostile environment on the Belleau Wood. On the Belleau Wood, Schindler was even afraid that his mail was being read, so he'd include a hand-made seal on his letters with a note: "void if seal is broke."

Heterosexist harassment

In letters back to his family, Allen R. Schindler Jr. referred to the ship as the "Helleau Wood" and repeatedly experienced heterosexist harassment. According to Human Rights Watch, Schindler complained to his chain of command about the harassment in March and April 1992, but nothing was done in response. In his complaint, Schindler reportedly cited an incident when his locker was glued shut, as well as constant comments from his shipmates saying "There's a f***** on this ship and he should die."

Rich Eastman, one of Schindler's former shipmates from Belleau Wood, told Esquire that he personally witnessed the frequent harassment. "People bumped into him and shoved him out of the way. They made comments – 'Queers coming down the passageway.'" Keith Sims, another former shipmate, said that on occasion, people would pretend to accidentally spill soup on Schindler.

According to "Unfinished Lives," during the summer of 1992, Schindler frequented the Navy Alcohol Rehabilitation Center in San Diego. But Schindler reportedly denied being an alcoholic and claimed instead that his superiors had ordered him to go to the center in response to his complaints about harassment. Meanwhile, the Navy has never acknowledged that Schindler reported harassment from his shipmates.

2-Q-T-2-B-S-T-R-8

Allen R. Schindler Jr.'s shipmates weren't the only ones that picked on him. According to Esquire, when Belleau Wood was pulling out to go to Hawaii, many sailors didn't get back from shore leave in time, including Schindler. However, Schindler was the only one written up for his absence.

Increasingly frustrated at the harassment, Schindler tried to let his "true colors" out, according to "Unfinished Lives." While on radio duty in September 1992, Schindler transmitted the message "2-Q-T-2-B-S-T-R-8" ("Too cute to be straight"), which reached most of the Pacific Fleet. Schindler was immediately charged with broadcasting an "unauthorized statement." Schindler requested a meeting with Captain Douglas J. Bradt, his commanding officer, and Captain Bernard Meyer, the ship's legal officer. At this meeting, Schindler came out as a gay man and was told that he would be discharged, though the administrative discharge proceedings would take a few weeks. Later, Schindler would write of the meeting in his journal, noting, "If you can't be yourself, then who are you?"

On September 25, Schindler's non-judicial proceeding regarding his unauthorized message was held. But while Captain Bradt could've held a closed proceeding, he held an open proceeding that ended up having over 200 sailors in attendance. At one point during the proceedings, Schindler covered the microphone with his hand and whispered to Bradt, "You know what I am." For the unauthorized broadcast, Schindler was sentenced to 30 days restriction to the ship and had his rank demoted from RM1 to RM3.

Allen R. Schindler Jr.'s final shore leave

Allen R. Schindler Jr. wrote in his journal on October 2, "More people are finding out about me. It scares me a little. You never know who will want to harm me or cease my existence." At the time of writing, Schindler still had three weeks of remaining on the ship while the Belleau Wood was docked at Sasebo Naval Base.

On October 23, Schindler's restriction was lifted and Esquire writes that he was overjoyed. He only had five days before Belleau Wood was headed to the Philippines, so every minute off the ship in Sasebo, Japan was precious time. While on shore leave, Schindler met Valan Cain, Natasha Rijnbeek, and Eric Underwood. Underwood recalls, "I kind of felt sorry for him. He was dealing with people who didn't understand him, or care to, and when he found people he could talk to, he was thrilled." When asked about the harassment he experienced, Schindler's only comment to them was that "he felt lucky not to have seen more."

Schindler also wasn't the only gay man on Belleau Wood being harassed. While Rich Eastman was asleep, he was assaulted and ended up with a bloody nose and a cut under his eye, as his attacker said, "We don't want any f*** on our ship. You better get off our ship."

Allen R. Schindler Jr. was beaten to death

On October 27, 1992, Allen R. Schindler Jr. bumped into Valan Cain around 7PM and told him that he'd swing by later that night to say goodbye to him and Eric Underwood. But by the time Underwood got back to his hotel around midnight, Schindler was already dead.

As Schindler walked through Sasebo after an AA meeting, he was followed by Terry Helvey and Charles Vins, both airmen assigned to the Belleau Wood. According to "Unfinished Lives," they followed Schindler into Sasebo Park and into a public toilet. In the public toilet, Helvey attacked, smashing Schindler's nose. Vins joined in as well, kicking Schindler's head and stomach, breaking ribs. Vims later testified that while Helvey repeatedly kicked Schindler's head, "it looked like he was kicking a soccer ball." As Schindler lay motionless on his back, Helvey stomped on his chest for at least 30 seconds. Commander Edward Kilbane, the forensic pathologist at Okinawa, testified that he'd never seen a worse beating. Schindler's injuries were "worse than the damage to a person who'd been stomped by a horse; they were similar to what might be sustained in a high-speed car crash or a low-speed aircraft accident," Esquire writes.

When Schindler was discovered, he was still alive, but unconscious, and his face was so disfigured no one could identify him. His nose was missing and "his jaw was unhinged, floating free." The seamen would only be able to identify Schindler because of his tattoos.

Arresting Terry Helvey and Charles Vins

Terry Helvey and Charles Vins left the public toilet at Sasebo Park covered in blood. According to Esquire, they sat down briefly at the Sasebo River and Helvey talked about how they could get back onto the ship without detection. But they'd already failed at avoiding detection, since Keith Sims had reportedly already seen them as they ran from the bathroom, per "Unfinished Lives."

As Hevley and Vins headed to the base, they were stopped by the shore patrol, who asked if they'd been in the park and requested identification. Helvey ran off, though he came back to push the shore patrol off Vins, and the two of them ran into a residential area. As they tried and failed to come up with an alibi, Helvey decided that he should claim that Allen R. Schindler Jr. tried to make a pass at him and that, as a result, he just "lost it." Around 3:30 AM, they returned to the base through a back entrance. There, they ran into a military policeman who was looking for two murder suspects. But the policeman told Helvey and Vins that they didn't match the description.

Around 6 in the morning, Helvey was taken to the master-at-arms's office. On the way, as he passed Gerald D. Maxwell, he said "I didn't mean to do it, but the bastard deserved it." Vins was also arrested, and although he initially confessed, he ended up taking a plea deal and testifying against Helvey.

Allen R. Schindler Jr.'s mother finds out the truth

On October 27, 1992, Dorothy Hajdys-Clausen was visited by two sailors who told her that her son had been killed. According to The New York Times, she was told that Allen R. Schindler Jr. had been "assaulted by two men in a park in Sasebo, Japan, and that he was dead" without any mention of who the attackers were. It wouldn't be until November 4, when Schindler's unrecognizable body was brought to Hajdys-Clausen, that she was told that Schindler was murdered by his shipmates. But no one from the Navy gave her any more information as to why her son's shipmates wanted to beat him to a literal pulp.

Meanwhile, Eric Underwood, Valan Cain, and Rod Burton (he'd met Schindler before his death), were furious that the Navy wasn't being honest about the nature of the crime, and wrote a letter to several newspapers and publications. The letter read, in part, "The reason for the murder was reported by the Navy as 'a difference of opinion' and not the grievous crime of 'gay bashing' that it was... Why should the death of an admitted homosexual be swept under the carpet by the U.S. Navy? Why does the U.S. military get away with this discrimination?" per Esquire.

The only one who picked up the story was Rick Rogers, writing for Pacific Stars and Stripes, and on December 6, he called Hajdys-Clausen to tell her what he'd learned about her son's murder.

Charles Vins takes a plea deal

Reporter Rick Rogers followed the story from the start and asked to attend the court martial, which is typically public and open to the press. However, Esquire writes that while Rogers was told that he'd be kept informed and allowed to attend, when Charles Vins was court-martialed on November 23, Rogers only found out afterwards.

Because of the plea bargain that Vins took, the maximum jail time he could serve was four months, and he agreed to plead guilty to lesser offenses in exchange for testifying against Terry Helvey. During the court martial, Vins' defense counsel even claimed that Vins "didn't throw a single blow. He didn't so much as make a single angry gesture toward Schindler." But in Vins' own account of Allen R. Schindler Jr.'s murder, he admitted that "using the toe of my right foot, I kicked Schindler on his left side. He did not fall backward, so I believe I kicked him in the same manner and the same location two more times."

It's unclear whether the military lawyer was intentionally or unintentionally looking to mislead the court, but according to "Unfinished Lives," Vins served 78 days of his sentence and was given a general discharge.

'I don't regret it. I'd do it again'

During his trial, Terry Helvey denied that he attacked Allen R. Schindler Jr. because he was gay. But according to The Tech, Navy investigator Kennon F. Privette testified that Helvey said "he hated homosexuals. He was disgusted by them." Helvey was also quoted as saying, "I don't regret it. I'd do it again. ... He deserved it."

The defense tried to argue that Helvey was a model citizen who murdered Schindler while under the abuse of alcohol and steroids. However, another witness testified that just two months before the murder, Helvey was also involved in an insurance scam. Before the sentencing, Helvey also read an "if-I-could-change-places-with-your-son" letter to Dorothy Hajdys-Clausen in the courtroom. However, according to "Unfinished Lives," Helvey maintained that the murder never would've happened if the Navy kept gay and lesbian people from joining. On May 27, 1993, Helvey was sentenced to life imprisonment and was given a dishonorable discharge from the Navy, writes Esquire.

Belleau Wood never shed its heterosexist reputation. In 1996, when a 21-year-old sailor faced a discharge for gay conduct, he was told to go quietly, otherwise he could end up like Schindler, and was told "The same thing will happen to you. You will be killed."

Allen R. Schindler Jr.'s mother speaks up

Allen R. Schindler Jr. told his mother Dorothy Hajdys-Clausen that he was gay in June 1990, but at the time she didn't believe him and insisted that he was "confused." And according to Chicago Tribune, even after learning that he was murdered because he was gay, Hajdys-Clausen was still hesitant to believe that her son was gay.

But after attending a memorial service held by the San Diego Veterans Association and meeting openly gay people for the first time, Hajdys-Clausen began to change her mind, especially once she realized that it was organizations like Queer Nation and not the Navy who were demanding justice for her son. "I saw that weekend that (gays) were just like anybody else. The boys I met weren't weird. They really loved my son, and they were hurting too. Some I think almost as much as me."

The New York Times reports that Hajdys-Clausen quickly became a spokesperson for gay rights and became active in lobbying Illinois for a gay-and-lesbian rights bill.

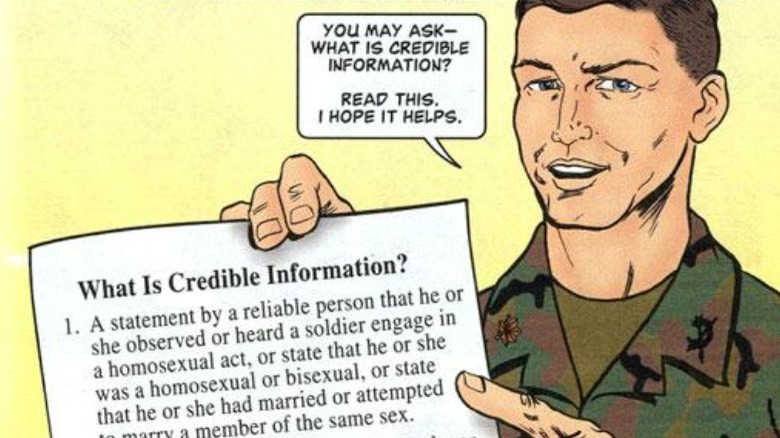

The 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell' bill

In 1982, the Department of Defense formalized their policy on gay people and stated that "homosexuality is incompatible with military service," officially banning gay people from the military. 10 years later, while campaigning to be president, Bill Clinton promised to lift the ban on gay, lesbian, and bisexual people serving in the military, Global News reports.

While President Clinton tried to overturn the ban, he faced pushback, and Congress tried to make the ban federal law. In an attempt to compromise, on December 21, 1993, the Clinton Administration issued Defense Directive 1304.26, which is what became known as "Don't Ask, Don't Tell."

But according to "Camouflaged," the full name of the compromise was "Don't Ask, Don't Tell, Don't Pursue, Don't Harass." While the directive maintained that anyone who was known to be gay or lesbian wasn't allowed to serve in the military, it also maintained that the military isn't allowed to inquire about someone's sexuality. And the "Don't Pursue, Don't Harass" part was meant to keep what happened to Allen R. Schindler Jr. from happening to anyone else.

The effect of 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell'

Unfortunately, the policy of "Don't Ask, Don't Tell, Don't Pursue, Don't Harass" did little to curb harassment and violence against gay, lesbian, and bisexual people in the military. While the "Don't Tell" part was often held up, the other four points were almost completely ignored. A survey done in 2000 showed that 85% of service members believed that offensive comments about gay people were acceptable and 37% witnessed or experienced targeted harassment in both verbal and physical forms. However, according to "Camouflaged," most didn't report the harassment due to fears of retaliation.

Tragically, the policy also didn't prevent murders from occurring. Less than seven years after Allen R. Schindler Jr.'s murder, in July 1999, infantry soldier Barry Winchell was beaten to death with a baseball bat by fellow soldier Calvin Glover after a "malevolent gay-baiting campaign" enacted by Justin Fisher, Winchell's roommate, writes Vanity Fair. Meanwhile, people like John McCain continued to maintain into 2007 that gay people in the military were an "intolerable risk to national security."

According to "Government at Work," it's estimated that during the "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" period, over 14,500 military personnel members were discharged for reasons relating to homosexuality.

Repeal of 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell'

"Don't Ask, Don't Tell" faced a number of legal challenges, but it was "upheld in federal courts five times" (via "Government at Work"). But at the end of 2010, Congress voted to end the "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" directive. Although the repeal was signed into law in December 2010, it didn't go into effect until September 2011 because the repeal included provisions that gave the Pentagon time to prepare and for military officials to "certify" its end, according to NPR.

However, NBC News reports that even 10 years after the repeal, the policy left behind a "hurtful" legacy. Many veterans who were discharged under the policy still don't have access to military pensions or medical care.

And although many who were discharged under "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" are now eligible to get their discharge upgraded from general discharge to honorable discharge, the Department of Veterans Affairs notes that many have not applied for a discharge upgrade "due to the perception that the process could be onerous."