The Untold Truth Of St. Peter's Basilica

Visit Rome and it's almost required that you take a day or so and explore the city-state known as Vatican City. It's the nerve center of the Catholic Church and one of the very few absolute monarchies left in the world, with the pope at its fore (via History). Even if you aren't going for spiritual purposes, this micronation surrounded entirely by Rome is packed to the gills with architectural wonders, ancient history, and jaw-dropping works of art. It's to the point where the entire Vatican has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. And at the center of it all is St. Peter's Basilica.

UNESCO notes that it's the largest single religious building on the planet, and it's often crowded with tourists and faithful alike who are there to gaze upon the sight of the church. Yet, a relatively speedy visit over the course of an hour or two is only going to help you learn so much about this historic church. From the necropolis beneath its floor to the monumental dome rising far above the crowd, this is the untold truth of St. Peter's Basilica.

St. Peter's Basilica was in development for over a century

Gazing upon St. Peter's Basilica today, you might think that it's been there for ages. And while it has stood in its spot since the 17th century, the truth is that the path to the church we see today was long and winding.

According to Britannica, the first idea for the church you see today came about in the 15th century. Pope Nicholas V was apparently tired of the site's preexisting church, now known as "Old St. Peter's Basilica." So, in 1452, he commissioned work on a new addition, but construction paused upon the pope's 1455 death. It started back up again in 1470, then was supplanted by work for an entirely new basilica in 1506.

Though Pope Julius II was responsible for the first stone laid for St. Peter's Basilica as we know it, that doesn't exactly mean it was completed in a timely manner. A constantly changing slate of architects and popes, who seemed to keep dying throughout the process (blame medieval and Renaissance medicine), slowed the process considerably. All of this meant that the basilica took over a century to take shape, reaching its more or less final form in 1615. Even then, the church has been subject to various tweaks and improvements over the years, including a grand piazza just outside that was designed by famed Baroque sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

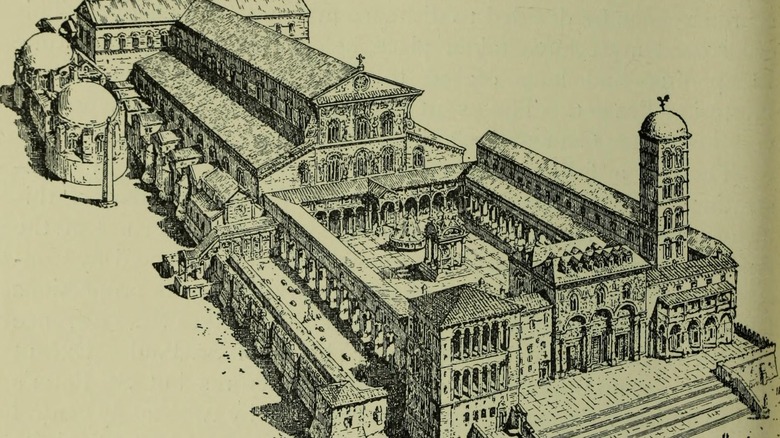

The basilica was preceded by another church

After all of the centuries-long hubbub over the basilica as it stands today, it can be easy to forget that it wasn't the first church on the site. In fact, St. Peter's Basilica is arguably the fourth in a series of religious structures that were built right there.

According to Encyclopedia.com, the very first of these construction projects was reportedly a relatively humble monument placed to mark the grave site of St. Peter after his execution during the reign of Emperor Nero in the first century A.D. The next was Old St. Peter's, the first proper church, which was built during the more Christian-friendly time of Emperor Constantine and his successors in the fourth century A.D. Scholars tend to count the other two churches as interstitial structures used during the seemingly endless 16th- and 17th-century construction period, followed by the St. Peter's Basilica that still stands.

Old St. Peter's was, by all accounts, a pretty impressive church in its own right. It boasted an extensive floor plan — this is the Vatican and the center of what was then more or less the entire Christian Church, after all — and that all-important connection to what many believed was St. Peter's grave.

It supposedly sits on top of St. Peter's tomb

The central focus of all the churches and religious monuments on the site of St. Peter's Basilica zero in on one man: St. Peter. And he was, to say the least, kind of a big deal. Per Britannica, Peter (who was originally known as Simon) was one of the original 12 apostles of Jesus Christ. Not only did Peter personally know Jesus from practically the beginning of the Messiah's ministry, but he continued on after Jesus' death as one of the growing religious movement's most prominent figures. Prominence has its downsides, however.

Non-Biblical legend maintains that Peter spent his final years in Rome, where he got on the wrong side of the authorities and was martyred. As Romans were wont to do in many tales of martyrdom, they crucified Peter; but, upon his request to not show up Jesus, they flipped him upside down (via Columbia University).

The Vatican claims that a memorial beneath the basilica's high altar was built long ago to mark the burial of St. Peter, now widely revered as the first pope. Tracing the history of the tomb and who may be in it gets complicated fast, however. Per Smithsonian Magazine, there are some bone fragments reputedly connected to the saint and which were excavated from beneath the basilica in the 1930s. Yet, there's no scientific way of proving the connection. For many, it remains all a matter of faith.

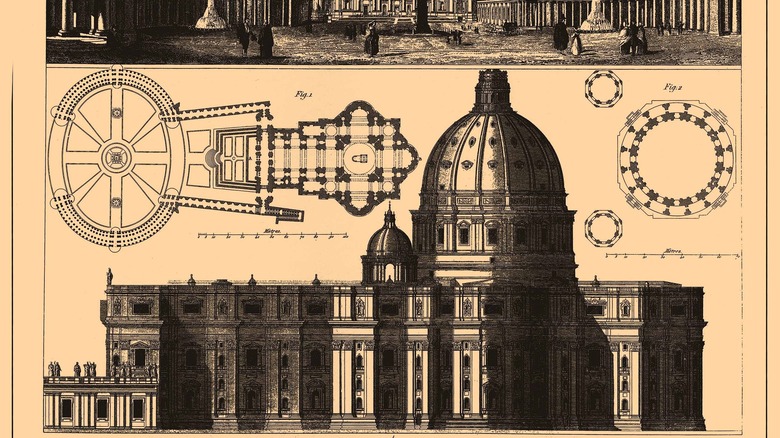

The church has a very intentional design

If you're not already familiar with medieval and Renaissance church architecture, then you may think that, well, a church is a church. It's a building with one big interior room for religious ceremonies, a few additions for various other purposes, and perhaps a creepy crypt or two beneath the main level. And while you'd be broadly right, it's clear that the designers of St. Peter's Basilica, along with many other religious buildings, put way more thought into the process.

First of all, as Britannica notes, the basilica is designed in a cross shape. The first architectural plans for the space laid it out in the shape of a Greek cross with equally-sized arms in all directions, as seen from above. Later takes focused more on the Latin cross shape, where a shorter cross arm is placed higher up on a longer vertical.

Meanwhile, its famous dome was such an impressive feat that it influenced later churches for centuries afterward. Modeled partially on the famous dome of the ancient Pantheon, a former Roman temple not too far away, it would eventually be even larger. Yet, as the journal Perspecta notes, it was originally going to be somewhat smaller, at least if Michelangelo were to have had his way. But, by the time it was completed in 1590, it was so notable that medals were minted with the structure displayed on the surface.

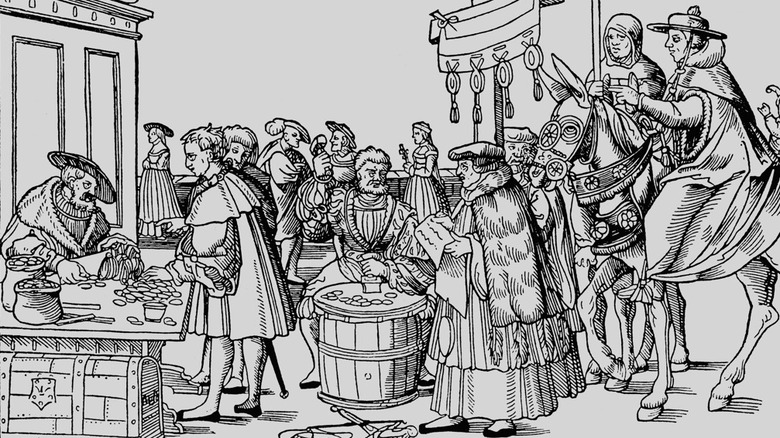

St. Peter's Basilica may have been built with dirty money

Construction projects, even those sponsored by ultra-rich and well-connected popes, don't come cheap. And even a single glance at the grandeur and opulence of St. Peter's Basilica will tell you that some serious money had to go into building this place. That's not so shocking, but the source of some of that money was perhaps so upsetting that it led some people to leave the church entirely.

According to a master's thesis from Rollins College, a portion of the early funding for construction came from indulgences, one of the more controversial practices of the Catholic Church during this time period.

Per ThoughtCo, indulgences were effectively cash payments meant to reduce sin and time spent in purgatory. But many argued that this was nothing more than a cheat and that true salvation could only be achieved through either good works or whether or not God had already decided if you were heaven-bound (depending on who you asked). For Martin Luther and other emerging Protestants, the flagrant use of indulgences were enough to make them break away from the church. And it could well be that the dramatic structure of St. Peter's Basilica represented such a moral thorn in many peoples' sides that they could no longer align themselves with what they believed to be a morally and spiritually corrupt institution.

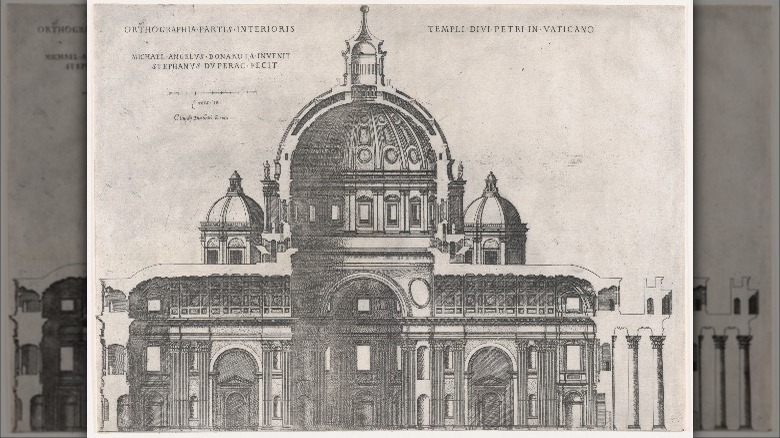

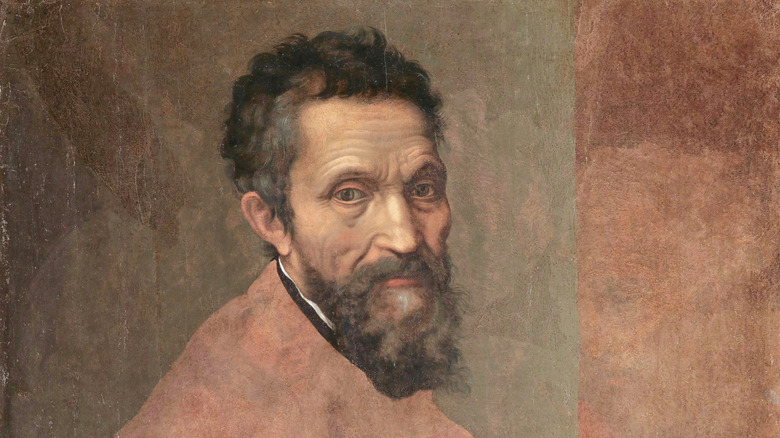

Michelangelo spent his twilight years designing St. Peter's Basilica

Michelangelo Buonarroti may be best-known amongst modern people for his visual art achievements like his elaborate paintings on the ceilings of the Sistine Chapel and a variety of sculptures like the world-famous "David". But, during his time, the artist was apparently seen as something more of a jack of all trades, at least when it came to art and art-adjacent tasks. At least, that must be why a 71-year-old Michelangelo received one last commission from Pope Paul III to design the increasingly complicated St. Peter's Basilica. According to Architectural Digest, Michelangelo was the latest in a line of architects who attempted to take on the sprawling, rather messy project. In fact, the self-taught architect may have tried to demur at first, claiming that he just wasn't up to the task, though it clearly was pretty hard to turn down a pope's request at the time.

However reluctant he may have been, Michelangelo had a significant hand in the final look of St. Peter's Basilica. True to his methodical nature — it took him four years to paint thousands of square feet of ceiling in the Sistine Chapel, per ThoughtCo — Michelangelo would spend 18 years in the process and would die before seeing the basilica completed. Yet, his work to install key structures, like the frame for the basilica's famous dome, ensured that his vision would be more or less completed as he saw fit.

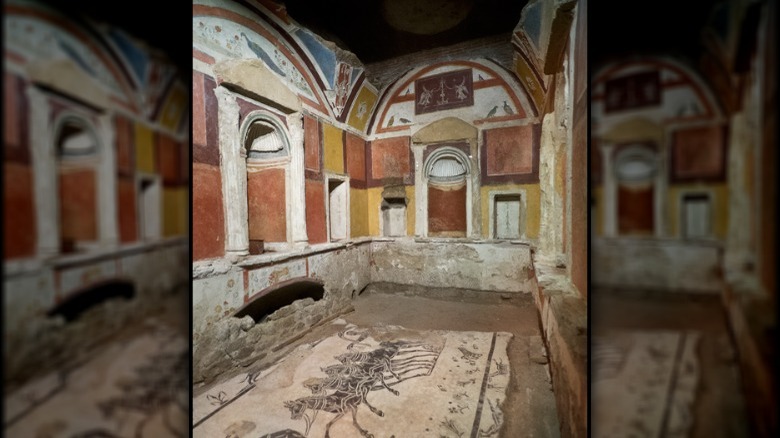

Many people are buried beneath the basilica

Known as the Vatican Necropolis, this burial complex dates back to the earliest church on site from the first-century era of Emperor Constantine. In the 1940s, Pope Pius XI, who wanted to be buried as close to St. Peter's remains as he could, commissioned an archaeological investigation of the necropolis. According to Aleteia, tradition held that Peter was martyred around 64 A.D. and then interred in a pagan burial ground. The fourth-century Constantine, who was decidedly more accepting of Christianity, had a church built on the spot, with the altar of the basilica supposedly sitting right above Peter's burial itself.

The investigation produced quite a few results, showing that many people had the same idea as Pius XI and had themselves buried nearby. A small box of bones, reportedly found with high-class purple cloth in a small niche, was uncovered during that first excavation. Yet Life reports that, in 1950, Pius XII said that we couldn't be sure they were Peter's and not the bones of one of the many buried in the necropolis. But his successor, Paul VI, turned around and said that the remains were probably the apostle's.

But, if we can step away from the Peter controversy for a moment, the excavations have uncovered a rich history of both pagan and Christian burials in the Vatican Necropolis, some dating back more than a millennium. Some even boast impressive artworks, like intricate tile mosaics and elaborate carvings.

The papal tombs beneath St. Peter's Basilica have a unique history

About a level above the more ancient tombs lies the final resting place of quite a few popes, as Life reports. Though not all pontiffs are buried beneath the church, quite a few have requested to rest near what they believe to be St. Peter's remains. And, as a floorplan of the grottoes on that level shows, their resting places are joined by a series of chapels, archaeological exhibit areas, and even a few burials of non-papal folks like cardinals and heads of state such as Christina of Sweden.

Some papal graves were destroyed or relocated in the transition from Old St. Peter's to the current basilica, though many were seemingly safe and sound in very solid stone sarcophagi. According to "The Deaths of the Popes," the destruction was largely the result of architect Donato Bramante, who oversaw a significant portion of the construction that changed things over from Old St. Peter's to the current basilica. Some of the sarcophagi are now on display in the grottoes, though others are now only remembered through records and sketches made by church historian Giacamo Grimaldi at the time.

Even the church's piazza is a grandiose spectacle

It's obvious enough that there's plenty to see within the walls of St. Peter's Basilica and, of course, visitors can get a pretty nice view just by looking at the church's monumental facade. But they should also turn 180 degrees and take in the view of the square just outside of the basilica. This piazza features a plethora of monumental columns, hundreds of saints' statues, and an elaborate fountain.

As the University of Washington points out, there was always some sort of space in front of St. Peter's Basilica. But the one tourists see nowadays is the product of a redesign by Baroque sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini in the 1650s. He produced a grand statement meant to reflect the basilica itself, as well as the message that the church welcomed the faithful with open arms and would shield visitors from the outside world. Bernini actually designed two sub-squares, the Piazza Obliqua (an oval-shaped space), and the more squared-off Piazza Retta.

There's even an ancient Egyptian obelisk there, perhaps a little strange for what's considered to be a Christian hub. PBS reports that it's bare of any inscriptions, making its history rather mysterious. As legend has it, the obelisk was left standing despite its pagan past because it had been a witness to St. Peter's martyrdom. Other tales, such as the one that claimed Julius Caesar's remains were encased in a metal globe on the top, haven't been definitively proven.

St. Peter's Basilica is packed full of art and treasures

For both faithful Catholics and people outside of the church, one of the greatest claims to fame for St. Peter's Basilica is its jaw-dropping collection of artworks. The most famous is arguably Michelangelo's Pietà, or "The Pity." Yet, per Columbia University, it wasn't originally meant for the basilica. Michelangelo originally sculpted it for the tomb of Cardinal Jean de Bilhères, but the statue was moved to its current location in the 18th century, long after anyone involved could object. It depicts the post-Crucifixion body of Jesus held by his mother, Mary, and has been widely lauded for its realism, humanity, and careful composition.

Of course, Michelangelo is just one of many artists whose work is packed into the church, including some pieces that may have been snatched up from the pagan-temple-turned-Christian-church known as the Pantheon (via Vatican City State).

Meanwhile, Gian Lorenzo Bernini's artistry wasn't confined to the exterior of the basilica or its piazza, either. In fact, according to the University of Washington, he maintained a pretty fruitful relationship with the church for many decades, encompassing a wide array of projects. One of the most eye-catching is surely the "Cathedra Petri" or "Chair of St. Peter." In Bernini's hands, the wooden relic is encased by gilded bronze and figures of angels (via Notes in the History of Art).

One artwork in the basilica has been the subject of extra drama

Perhaps because it's one of the most famous artworks in the basilica, Michelangelo's Pietà sculpture has been the focus of much attention over the years. And some of that scrutiny has resulted in some seriously bad press for this centuries-old masterpiece.

Michelangelo's Pietà has been seriously damaged at least twice over the years, starting with an 18th-century incident. According to "Young Michelangelo," the fingers on the Virgin Mary's left hand were accidentally broken. They were subsequently restored by Giuseppe Lirioni in 1736, but now some wonder if Lirioni may have taken some artistic liberties and imparted his own take on the positioning of the fingers in question.

But the most shocking incident in the history of the Pietà happened right in front of numerous onlookers within St. Peter's Basilica in 1972. That's when Lazlo Toth, a Hungarian man, climbed over a barrier and dealt 12 punishing blows to the marble statue while proclaiming loudly that he was Jesus Christ. According to a report from the New York Times, the face, veil, and left arm of the Virgin Mary portion of the sculpture were badly damaged. According to Reuters, restorers painstakingly reconstructed the statue out of hundreds of fragments, using a combination of marble dust and special glue to make the joints practically invisible. Ten months after Toth's attack, the statue went back on display, this time behind bulletproof glass.

The basilica has a special Holy Door

Like many other Catholic churches and cathedrals, St. Peter's Basilica has a dedicated "Holy Door." Normally mortared shut, it's sometimes opened by order of the Pope during special years typically known as Jubilee or Holy Years. According to the Vatican, the pope ceremonially opens the door by striking it with a hammer. The hammer is traditionally made out of precious materials like gold or silver, though medieval and Renaissance popes may have occasionally used a more humble tool, presumably borrowed from the masons sent to actually dismantle the bricks and mortar around the door.

When it's time to close the door again, the pope takes part in another ceremony where he symbolically mortars the door shut again, though the actual work is left to proper masons who complete their work while psalms are chanted. During the ceremony, the pope also shows various relics, prays, and gives a final blessing.

Visitors who pass through the door during a Jubilee Year may believe that they'll receive a symbolic blessing or renewal. In 2015, when Pope Francis opened the Holy Door in St. Peter's Basilica, he dedicated it as a symbol of hope and urged Catholics who passed through it to take on the role of the Good Samaritan from the Bible (via BBC).