The Untold Truth Of The Book Of Psalms

The Bible isn't one book, but rather, it's a collection of 66 different books, written (or compiled, depending on your point of view) over centuries by multiple authors and editors in any of three different languages. Within those books are multiple literary genres, according to Bible Gateway, ranging from census figures, to written laws, to historical narrative, and just about everything in between.

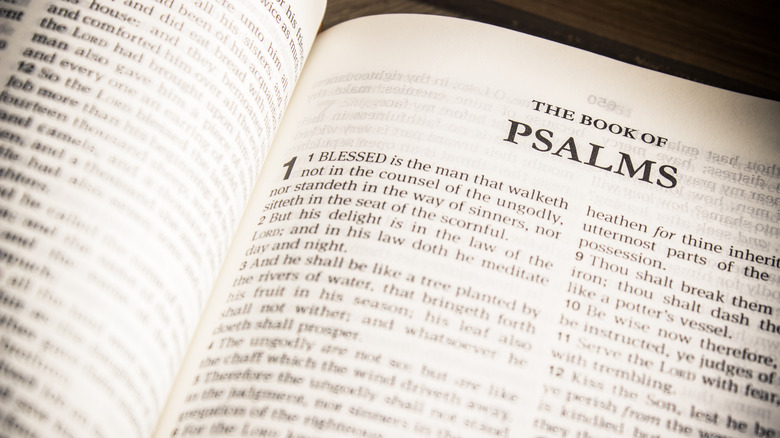

One such genre is poetry, and the Old Testament is chock-a-block with it. Entire books, such as Ecclesiastes and Song of Songs, are basically either poems or compilations of poems. But the cornerstone on which the Biblical poetry genre is built is likely the Book of Psalms, a collection of 150 texts, most of which are poems or songs (or both). And even within the Book of Psalms itself, there are multiple sub-genres of poetry. What's more, scholars believe that the entire book wasn't written by one person, but several.

At least seven authors contributed to the Book of Psalms

As Jeffrey Kranz notes at Overview Bible, it's convenient to say that the Psalms were written by David, the King of Israel, about whom much of the historical narrative of parts of the Old Testament were written. As a poet and court musician, it stands to reason that he would be responsible for many of the Bible's poems and songs, and indeed he is — but not all of them.

Specifically, some scholars believe that David is responsible for at least 73 Psalms, possibly as many as 84 of them. But the Book of Psalms contains 150 such passages. Another 12 are attributed to a colleague of David named Asaph, 11 to another man, named Korah, 50 to unattributed Psalmists, and five of them to four other men between them. What's more, many of the Psalms were written hundreds of years before David lived; others, hundreds of years after he died.

Many psalms are hymns of praise

As Bible Study Tools notes, a good portion of the Book of Psalms is given over to songs and poems of praise. In these psalms, the writer praises God for something — perhaps God's role in the life of the psalmist, or perhaps an incident in Israel's history in which God saved his people. Other passages simply praise God for his role as creator. A whole category of psalms is given over simply to praises of God for manifesting his presence on Mount Zion; these are known as the Songs of Zion.

In psalms such as these, the writer's joy is downright palpable. For example, in Psalm 144, David writes joyfully of being so moved by God's deliverance that he intends to praise God with musical instruments. "I will sing a new song to you, my God; on the 10-stringed lyre I will make music to you, to the One who gives victory to kings, who delivers his servant David," David wrote.

There are hymns of thanksgiving

Thanksgiving and joy would seem to be one and the same, but in fact, they're not. A person expressing joy can be thankful, of course, and a person expressing thanks can be joyful, but that doesn't necessarily mean that the two always have to go hand-in-hand. This is apparent in the genre of psalms known as the Thanksgiving Psalms, wherein the writer praises God for his (God's) personal intervention in the life of the writer or in the nation of Israel as a whole.

For example, Psalm 51 can hardly be described as joyful, though the writer's deep and enduring thankfulness comes through in the text. The psalm's writer, David, was in no way joyful at having committed his sin of adultery with Bathsheba, but God had forgiven him, and in response, David wrote a heartfelt song of thanksgiving. "Let me hear joy and gladness; let the bones you have crushed rejoice. Hide your face from my sins and blot out all my iniquity," he wrote.

Many psalms express sadness and lament

A pretty fair plurality — just over one third — of the psalms are anything but joyful. Mournful laments make up a good chunk of the collection. As Bible Study Tools notes, many of these sorrowful passages mention unspecified enemies bearing down on the writer, including vague references to real events in the history of Israel that the writer may be obliquely referencing. This ambiguity was deliberate, according to Bible Study Tools, because it allowed the psalm to be used by any generation in history to reference what may have been going on in their life, regardless of the historical reference contained within the text.

Other lamentations in the psalms are of a national nature; the writer mourns the state of his nation, often brought on by their failure to stay true to God. In other cases, the laments are personal, wherein the writer mourns his own failures to please God. Still others mourn God himself, such as Psalm 22, where the writer complains that God has "forsaken" him.

And then there are the imprecatory psalms

The emotions conveyed in the Book of Psalms are all over the place: from joyful praise, to mournful lament, to heartfelt gratitude, and everything in between. But there's one category of psalm that touches on another human emotion: rage. And in some of the psalms, that rage is palpable, all-consuming, even infanticidal. Bible scholars call these the "imprecatory psalms," according to Got Questions.

Considering that the psalmists lived in tribal societies in which invasion and enslavement from neighboring tribes was an everyday possibility, sometimes the writers' rage against their enemies comes through loudly and clearly. In what may be the most famous such passage, Psalm 137, the writer is so enraged at the destruction of Jerusalem that he envisions grabbing the babies of his enemies and smashing their heads against rocks.

These imprecatory psalms wind up in the New Testament, in which Jesus quotes them, not because he advocated vengeance, but because he wanted to juxtapose their words with his own appeal to love your enemies, as Got Questions notes.