What Life Was Like During The Plague Of Justinian

The black plague is considered one of the deadliest outbreaks in history. It killed millions of people in the Middle Ages, and it devastated the social and economical foundation of Europe for decades.

The bubonic plague is caused by the Yersinia pestis bacterium. According to the CDC, the most common form of transmission is through the bite of an infected rodent flea, although it's also possible for human fleas and body lice to carry the infection. It's hard to tell how the plague spread so quickly during ancient times, but at a time when hygiene wasn't the highest priority, lice, fleas, and rats were basically everywhere.

The most obvious sign of infection is very swollen, painful lymph nodes (buboes), but patients also developed sudden high fever, chills, vomiting, diarrhea, and horrible pains (via History). According to Bandolier, the bubonic plague has historically killed 50-70% of those infected.

The plague still exists today and cases are reported in many countries around the world. According to the CDC, an average of seven cases of plague are identified in the U.S. every year. However, the Yersinia pestis bacterium can be treated with common antibiotics, so the risk of death is very small today compared to hundreds of years ago. In fact, according to Bandolier, you are just slightly more likely to die of the plague today than from a lightning strike.

There were three major plague outbreaks

Most people think of the Middle Ages when they think of the black plague. That's because the largest outbreak of the bubonic plague happened between 1347 and 1352, brought to Europe from Asia via commercial ports and trade routes. This was also the outbreak when plague doctors and their unforgettable image first appeared. This particular outbreak of the plague killed over 25 million people in Europe alone, according to Britannica.

For the next few centuries, the plague would come back in small clusters here and there, until another major pandemic broke out in the 1800s. This time it started in China, spreading via opium and trade routes and eventually reaching Australia. It was during this outbreak that scientist Alexandre Yersin identified Yersinia pestis (hence the name) as the culprit behind the illness (via JMVH).

But long before the 14th-century black plague decimated Europe, there was another pandemic, now considered the first documented pandemic in history. It's known as the Justinian plague of 541-544, and only recently historians have determined it was also an outbreak of bubonic plague. Because records from the time aren't as detailed and medicine was a lot more precarious, we know a lot less about this pandemic than the later ones.

According to JMVH, historians do know this outbreak started near Egypt in 540 and spread via ships traveling trading routes. A year later, it had arrived in Istanbul and to the heart of the Byzantine Empire.

The Justinian plague was very deadly

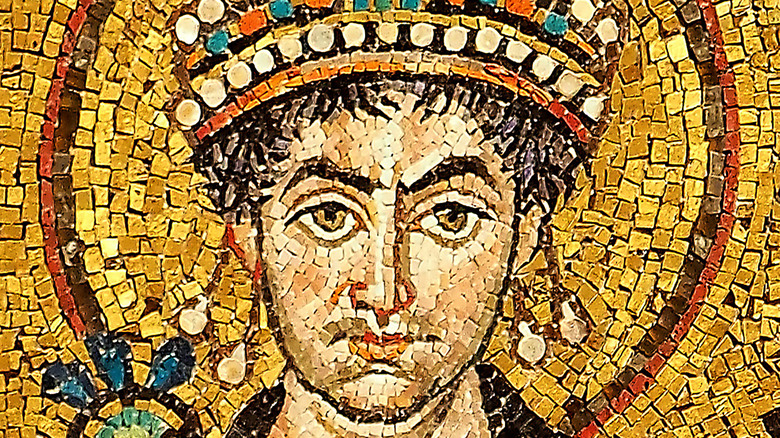

This outbreak of the plague would eventually become known as the Justinian plague after Justinian I, the Roman emperor ruling over Constantinople.

The Justinian plague spread through the Byzantine Empire very quickly. By the spring of 542, Constantinople was losing 5,000 citizens every day. According to Procopius of Caesarea, the Byzantine court historian, the pandemic spread so quickly that "with the majority it came about that they were seized by the disease without becoming aware of what was coming either through a waking vision or a dream" (via JMVH). The bubonic plague would go on to kill a third of the population of Constantinople.

The bubonic plague raged through Europe, the Middle East, and Asia for years to come. Estimates put the death toll at 100 million between the years of 542 and 546. Although historical reports seem to indicate the plague disappeared from the Byzantine Empire after that, it returned to Constantinople in the years 573, 600, 698, and 747 (via JMVH). By the seventh century, the plague had reached Ireland and England and became known as "The Great Plague of 664." Old records describe it as "a sudden pestilence which carried off many throughout the length and breadth of Britain" (as quoted via Oxford Academic).

By the mid-eighth century, the Justinian plague had vanished as quickly and mysteriously as it appeared. The next big plague wouldn't come around until the black plague ravaged Europe in the 14th century, according to JMVH.

Life during the Justinian Plague was a nightmare

Even if you somehow managed to survive the plague itself, there were many other horrors waiting for you. The Justinian plague killed so many people that it quickly affected farming and the food chain. According to Procopius as quoted by PassportHealth, the plague wiped out much of the farming community, causing desolation and hunger. "Even then, [Emperor Justinian] did not refrain from demanding the annual tax, not only the amount at which he assessed each individual, but also the amount for which his deceased neighbors were liable."

With fewer workers tending to the land, crops died and there was simply not enough food for everybody. Any food was suddenly very expensive, as the low production meant grain prices soared. According to World History Encyclopedia, the Justinian plague weakened the Byzantine Empire tremendously. The army got weaker and smaller, unable to stop attacks from outside forces, and the empire's population suffered immensely due to hunger, disease, and poverty.

Since cremation wasn't a proper "Christian option," dead bodies soon started to pile up on the streets. To clear them up, trenches were dug up outside the cities and the dead stacked up and left to rot. In populated places, bodies were placed inside buildings, towers, and churches or taken to the coast and dumped into the sea.

Poor medical care made things worse

Medicine wasn't exactly very advanced in the sixth century. Doctors at the time followed the teachings of Galen of Pergamum, a Greek physician who believed illnesses were caused by unbalances between the four humors in the body (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile) and nature's elements (earth, air, fire, and water). This meant most treatments were aimed to restore that balance and were, as a result, mostly ineffective.

During the Justinian plague, physicians relied on Galen's recommended treatments, such as plenty of herbal concoctions and bloodletting (via Encyclopedia). Doctors would also sometimes lance the buboes to let the infection out after discovering some patients were more likely to recover this way (via Psychiatry of Pandemics).

While medical treatment left much to be desired during the plague, people without access to physicians were in an even worse situation, as they had to treat themselves. According to World History, this included anything from cold water baths to "blessed" powders and amulets. Burning sweet-smelling substances or drinking Stabian milk were also potential cures recommended for a number of diseases, including the plague (via Galen's Treatise).

As a last resource, those infected could go to a hospital. The Byzantine Empire was one of the earliest empires to have established places where the public could be treated for medical issues but also be provided with proper food, clean water, and spiritual comfort (via "The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity").

The Justinian plague had lasting consequences

The plague that swept through the Byzantine Empire had especially dire consequences for Constantinople. Once buildings and towers were full of corpses, the city built a mass graveyard in Galatia, but that too was soon filled with over 70,000 corpses. Not only were further illnesses and infections born out of this, but historians describe the smell of death taking over the cities for months (via Medievalists).

Merchants and businesses closed their doors, and soon famine became an additional major issue to deal with. With agriculture also collapsing, the economy struggled for years. Shortage of grains and wine (a significant part of the Byzantine diet, as water wasn't exactly clean back then) followed soon after. Four years later, when the Justinian plague resurfaced again, there was a serious shortage of bread. It lasted three months and caused rioting. Then in 552, the plague came back again and this time it particularly affected animals, killing not only thousands of dogs and cats, but also mice and reptiles.