10 Best Benjamin Franklin Inventions

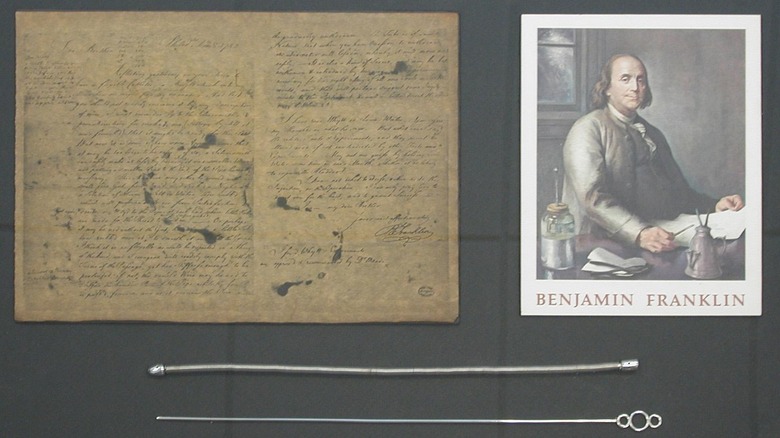

In the context of American history, Benjamin Franklin is a lot of things. For some people, he's the guy on the $100 bill. For others, he's the staid Founding Father who helped usher in the American Revolution and quite a few of its key documents, like the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, and the United States Constitution. And, if you do a bit of digging into his personal past, you may also learn that he was a somewhat libertine sort of man for his time, charming members of the opposite sex as he made his way through colonial America and the political and social spheres of 18th century Europe.

But, while all of those things were certainly a part of Benjamin Franklin, they are not the whole story. Franklin was also, by all appearances, an intellectual powerhouse and someone whose curiosity simply never left them. In between all of the writing, printing, diplomacy, and work of forging a new nation, Franklin also found the time to invent quite a few things. Some may seem pretty obviously interesting at first glance, like his early innovation of swim paddles. Others, like the hoary old Franklin classics of bifocal glasses and the eponymous Franklin stove that you've probably read about in some simplified historical summaries, deserve a second look. Even his take on the seemingly humble soup bowl tells us a lot about the man and his time. Discover the 10 best Benjamin Franklin inventions.

Swim paddles

For the people of colonial America, swimming had an interesting status. Though it seems that you would have been hard pressed to find Olympic-level swimmers among the European-descended colonizers, given the reports of people who perished while swimming, it was an apparently popular practice, according to Colonial Williamsburg. Even a young George Washington reportedly enjoyed a swim in Virginia's Rappahannock River, at least until he discovered that someone had stolen his clothing from the river bank. Besides that incident, the general impression was that the greats of the ancient world, like the Romans, had swam for their strength, health, and general enjoyment. So, why shouldn't colonial folks do it, too? It seems to have been especially popular amongst boys and men of the era, who weren't above taking a dip in a nearby creek, river, or lake.

By all accounts, young Benjamin Franklin was a pretty avid swimmer. But he clearly thought that there was room for improvement, given that one of his earliest known inventions was a pair of wooden swim paddles. According to his own essay, "On the Art of Swimming," the paddles were oval shaped and had a thumb hole so that he could grip them more securely. They were decently successful overall, but Franklin admittedly didn't have the advantages of modern day materials or else just got tired of the process. "I remember I swam faster by means of these [palettes], but they fatigued my wrists," he concluded (via The Franklin Institute).

Franklin stove

The Franklin stove may be one of those things that you vaguely remember from a history textbook that was trying hard to convince you that Benjamin Franklin was a pretty cool guy, actually. And though the idea of some long-dead dude inventing a stove may have been yawn-inducing in the eighth grade, the Franklin stove was actually kind of a big deal.

As The Franklin Institute points out, winters in the American British colonies could be wickedly cold, and colonizers relied on burning wood to stay warm. Franklin's stove design was meant to make the best use of wood fires as possible, letting less of that precious heat to escape up the chimney and into the cold air. Moreover, the structure of the stove, with hollow elements and an inverted siphon, more efficiently brought in air to fuel the fire and generate even more heat.

"Benjamin Franklin's Science" notes that Franklin was probably taking his cues from German settlers in Pennsylvania, who added a cast iron box to their hearths. His design took on this ingenuity and combined it with a British-inspired love of more aesthetic but less efficient open-flame hearths. Even better, as The Franklin Institute notes, was the fact that this design produced less smoke overall, leading to cleaner homes and lungs.

Soup bowl

Not every invention has to be of the sort that gets a paragraph or two in your history textbook, nor does it have to be so flashy that it's reproduced over and over in lithographs and quasi-historical tales about someone's life (looking at you, Benjamin Franklin and the kite in a lightning storm). But, just because something is a humble creation doesn't mean it can't be at least a little brilliant. Enter Franklin's soup bowl.

Yes, really, we're going to talk about tableware. Don't go away just yet, though, as this weird little piece of culinary history can actually tell us a lot about Franklin's proclivities and what it meant to travel and dine in style in the 18th century.

According to the Smithsonian, Franklin's divided soup bowl was at least tangentially connected to Franklin's own desires. Or, more specifically, his desire to take full advantage of what sounds like a voracious appetite without making a mess of himself. Essentially, the bowl consisted of a relatively large main depression surrounded by a ring of smaller ones. The idea was that if Franklin were to find himself dining on a delectable soup at sea, the heaving of the boat on the waves would slop the liquid into the smaller bowls and not onto his clothing. It wouldn't do for an inventor, statesman, and ambassador like Franklin to show up to a shipboard function with potato soup all over his fine waistcoat, would it?

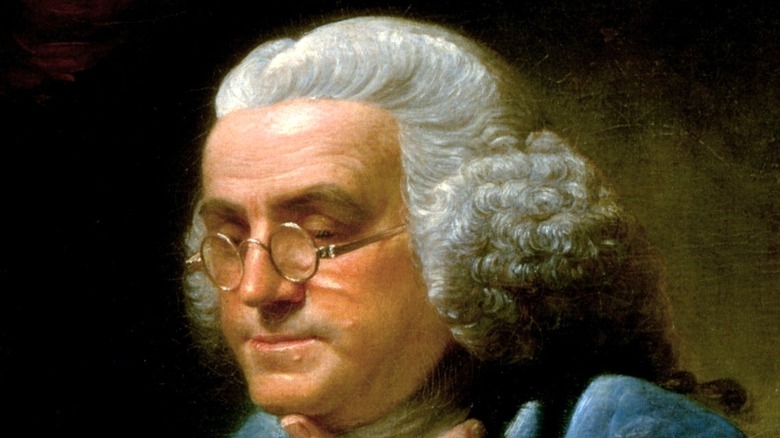

Bifocal glasses

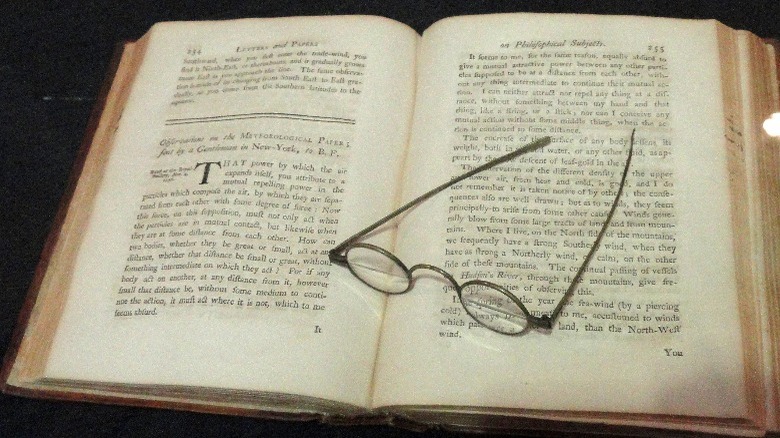

In colonial America, glasses were one of those things that tended to set the wearer apart. According to "The First Scientific American," they were generally understood to be medical devices, but also ones that had a certain edge of scientific innovation to them. If you wore glasses, you may have been able to present yourself as someone on the cutting edge (who also had weak eyesight, sure). When Benjamin Franklin developed an even more advanced pair of spectacles, it likely helped to further set him apart as an intellectually curious innovator in the colonies and beyond.

The glasses in question were bifocals, not unlike the kind you might pick up at an optometrist's today. If you aren't familiar with the concept, bifocals allow the wearer to focus in on things that are close and far away, depending on what section of the lenses they look through. Typically, the upper portion of the bifocals allow you to view things far away, while the lower section lets you focus in on things that are closer to you, such as the text of Franklin's beloved books.

Today, bifocals and similar glasses like trifocals are made in a relatively seamless fashion. Franklin, however, apparently took two different lenses and cut them in half. He then joined them together, seams and all, in a set of frames, per the Smithsonian. It's not exactly the smooth transition of modern lenses, but one that seemingly pleased him all the same for the concept's versatility.

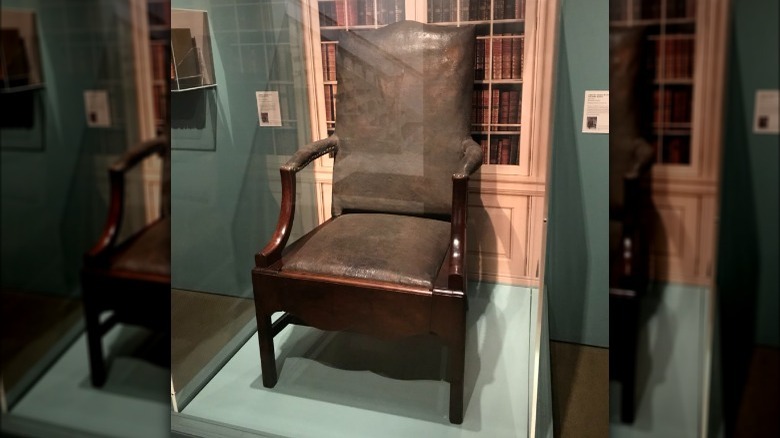

Library chair

At this point, it's probably fair to say that Benjamin Franklin was a nerd. We mean that in the most positive way, of course, since it's clear that every society should have at least some people who are voraciously curious. And, for those folks who enjoyed the benefits of the Franklin stove or his bifocal glasses design, it was clearly a boon. It would be even more so for those who were so lucky as to have access to a library like Franklin's, too.

That was doubly true if they wanted to hang out in a chair and read. The Benjamin Franklin Tercentenary exhibition included a chair designed by Franklin that featured a step stool added onto the frame — all the better to reach books with, of course. PBS reports that another chair of Franklin's reportedly sported a fan that could be operated by a foot pedal, which would have surely been a relief to a dedicated bookworm during the sweltering humid summers of Philadelphia and other regions in the American colonies.

PBS also notes that Franklin is credited with inventing an extending arm to more efficiently reach books on high-up shelves in his library. It operated in a similar manner to grabbing arms today, with two pincers that could open and close with the help of a cord. Between this reaching invention and the all-purpose reading chair, Franklin could more easily get just the right volume he needed in just a few minutes' time.

Lightning rod

One of Benjamin Franklin's most famed interests was electricity. Clearly, there were no lightbulbs, no wiring systems, and no electricians at the time. But people knew that electricity was a very real natural force. One only had to take a glimpse at the awesome power of lightning to understand that something really interesting was going on.

While it's safe to assume that a majority of people were only going to glimpse lightning from within a safely sheltered building, Franklin's curiosity wasn't going to let him sit by and observe from a distance. He's now pretty famous for his experiments with electricity, including one where he flew a kite during a storm to demonstrate the connection between electricity and lightning. According to The Franklin Institute, this doesn't mean Franklin "discovered" electricity. And the kite wasn't struck by lightning — instead, it picked up ambient static electricity. Otherwise, Franklin and his son — who accompanied his father on the experiment — could have easily ended up smoldering corpses.

But Franklin does get credit for inventing a specific type of lightning rod. The Franklin Institute explains that lightning was a pretty destructive force that could seriously damage buildings. He realized that an iron rod, affixed to a high point on a building and grounded to another spot away from the structure, could alleviate a lot of that risk. His variation, which came with a point rather than a rounded end, was ultimately installed on quite a few structures.

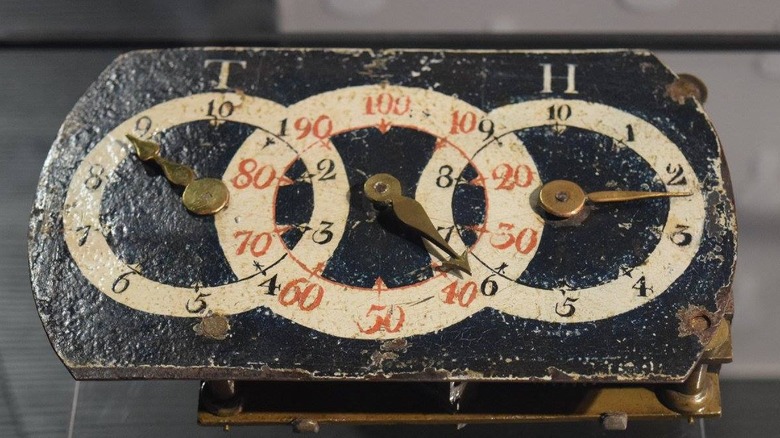

Odometer

To be perfectly clear, it's well-documented that Benjamin Franklin did not invent the very first odometer ever. In fact, he was a bit late to the game, though it's not his fault that he was born centuries after the first distance-counting machines were first developed. According to ThoughtCo, a very early version of an odometer, which is a tool meant to measure the distance a person or vehicle travels, was created in 15 B.C. by Vitruvius, a Roman engineer. Vitruvius' invention used a mechanism to drop a pebble into a box for each mile traveled. Other versions of the odometer were created in the 17th and 18th centuries, including one by inventor, mathematician, and physicist Blaise Pascal.

However, Franklin's own take on the tool was uniquely developed and employed for a very practical purpose. When Franklin was serving as Postmaster General — a post he only held for about a year, according to History – he became pretty interested in figuring out the best mail delivery routes. Like an efficiency-conscious UPS manager, he decided that he needed more data. So, per PBS, he developed an odometer that he could attach to the wheels of a carriage, which was then sent out to deliver the mail. When it returned, Franklin or another manager could take the odometer, see how many wheel rotations had taken place on the trip and, with the help of a little math, could figure out a good approximation of how many miles the mail delivery carriage had traveled.

Glass armonica

Benjamin Franklin was clearly a cultured man. When he was deployed as an ambassador to Europe in the aftermath of the American Revolution, per the U.S. Department of State, it became obvious that Franklin knew how to make a good impression.

Part of being a cultured person at this time was having an appreciation for the arts. And Franklin apparently was no exception. Take the glass armonica. According to The Franklin Institute, one of the more popular party tricks at this time, on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, was to hold a musical performance using glasses filled with water. Filled with the right amount of water and with the correct technique, the glasses can be made to "sing," resonating like a musical instrument. In fact, you may have seen this done or even attempted it yourself.

But Franklin apparently wasn't interested in what must have been a pretty laborious setup. You know, you'd have to get out all of the different glasses, figure out just the right amount of water for each one, remember what order to set them up in, and then play your tune. Franklin's glass armonica sought to simplify that process. It was essentially a wooden cabinet with the glasses already nestled together. A mechanism would set it to rotate and, with moistened fingertips, a musician could theoretically play it with ease. At the time, the glass armonica was one of Franklin's biggest hits, though its popularity faded in the decades following his death.

Flexible catheter

Okay, we have to be forthright about Franklin's invention of the flexible catheter. Is it glamorous? No. We can be reasonably certain that Ben didn't break this particular innovation out at parties, at least not the ones where he was trying to impress women (he did have a reputation as a serious skirt chaser who just couldn't help himself around pretty ladies).

But, if you were in Franklin's time and needed a catheter for a medical procedure, rest assured you'd be pretty grateful for a flexible version. Now, medicine in colonial times was certainly more advanced than in ancient or medieval eras and, as Harvard Library notes, more and more people had access to professionally trained doctors. But neither did colonial people enjoy the technological and research innovations we do today, like ultrasounds, double-blind drug trials, or flexible tubing. And if you needed a catheter to relieve a painful issue, things could get a little eye-widening.

Benjamin Franklin tried to alleviate some of that with his take on a flexible catheter. Instead of a single, unyielding length of metal tubing, his catheter had a series of joints along its length (via The Franklin Institute). He designed it, commissioned a local silversmith to craft the catheter, and then mailed the creation off to his own brother, who had been suffering with kidney stones. It's not clear whether or not Franklin's brother actually used the device, but it must have been at least somewhat more palatable than the shudder-inducing alternatives.

American political cartoons

Benjamin Franklin helped to establish a subscription-based lending library in 1731 Philadelphia, per the Benjamin Franklin Historical Society, and was also obviously someone who not only knew how to read but deeply loved the pursuit of knowledge. What's more, young Franklin truly made his mark as a prolific writer and printer, oftentimes writing satirical and incisive essays and pamphlets under a variety of pseudonyms (via The Library Company of Philadelphia). During his growth as a commentator and writer, Franklin developed a keen sense of evaluating society, individuals, and, of course, the political landscape.

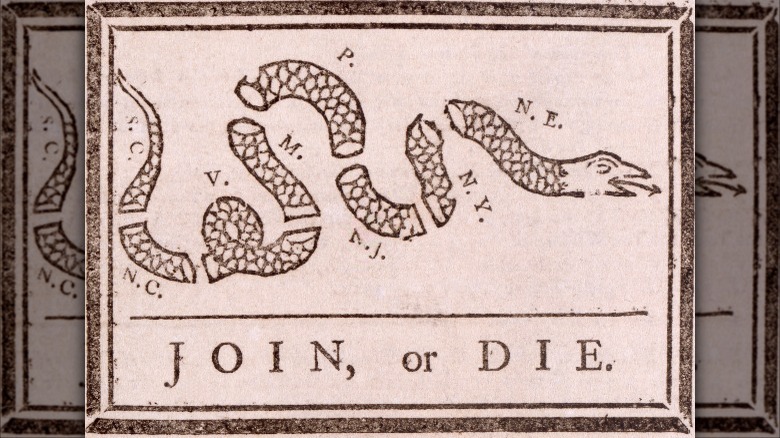

All of this led to what may well have been the very first American political cartoon, courtesy of none other than Franklin. And, no, it doesn't have much to do with the American Revolution, at least not directly. According to History, it's actually related to the French and Indian War. Published in Franklin's Pennsylvania Gazette newspaper, it depicts a snake cut into various portions, each labelled to represent the colonies. Beneath it is the stark maxim, "Join, or Die." The image, which became widely known soon after its first printing, essentially told the colonists to get their act together lest outside forces enact a bloody takeover.

For better or for worse, Franklin can be considered the father of U.S. political cartooning. Every newspaper political cartoon that's either made you nod in agreement or roll your eyes in exasperation owes some portion of its existence to Franklin's 1754 depiction of a dissected snake.