The Untold Truth Of Robert The Bruce

Sure, we all probably know about William Wallace. Or, at least we kind of know about him and his time, as filtered through 1995's epic film "Braveheart." But, as you may well have guessed already, the world of 14th Scotland was no gauzy romantic sequence, nor was it a dramatic yet still oddly cleaned up series of medieval battles. And, though William Wallace was very much a key figure in Scotland's struggle to separate itself from England's control, he wasn't the only person in the mix. Indeed, given that Wallace met his rather gruesome end in 1304, per the BBC, he simply wasn't around long enough to see Scotland secure its freedom.

But Robert the Bruce was. Indeed, given that Robert is now widely acknowledged as the first king of a fully independent Scotland, it's hard to deny his role in the process. In fact, Bruce was a pretty big deal in Scottish history, not to mention a complicated person whose route to the throne of his country included a considerable share of death, imprisonment, subterfuge, and general upset. Oh, and he was also excommunicated by the pope.

Today, Bruce is now known as one of the biggest names in Scottish history. And though he occasionally attempted to work with the English royals who were trying to overtake his peoples' land, neither was he the somewhat weasel-like character briefly portrayed in "Braveheart." This is the untold truth of Scotland's Robert the Bruce.

Robert the Bruce came from a noble family

Not only does "Braveheart" get William Wallace wrong — he was a relatively well-off knight, according to Britannica — but it also plays pretty fast and loose with Robert the Bruce.

The truth is that Robert, born in 1274 in Turnberry Castle, was a distant relative of Scotland's royals. He was even given the earldom of Carrick by his father in 1292, according to the World History Encyclopedia. What's more, young Robert was one in a growing line of Bruces who were moving ever closer to the Scottish throne, bolstered by their noble heritage and the numerous lands they held in both Scotland and England.

He also spent much of his early life in London, England, and would have likely lived for a time in eastern Ireland or the Western Isles (now the Outer Hebrides) of Scotland. As to whether or not he could speak French, as many Anglo-Norman nobles of the time did, it seems like that he at least had a noble's command of the language. According to the BBC's History Extra, while it's more likely that Robert was fluent in Scots and Gaelic, he was known to spend time at the English court, which did lean in a decidedly French direction. He also translated French literature for entertainment, showing that he was pretty well educated for the time.

Political crisis opened the way for Robert the Bruce

Things began moving into place for the young Robert in 1286. That's when Alexander III of Scotland died, setting off a succession crisis. According to the BBC, Alexander had been traveling south to meet his new wife, the French Yolande de Dreux. At some point, both nightfall and poor weather separated the king from his group. He was found dead the next morning, having apparently fallen off his horse.

Alexander had named his granddaughter, Margaret, his successor. Yet, as National Museums Scotland reports, the seven-year-old girl died only four years later. This left the throne of Scotland wide open and the country in upheaval over who, exactly, should occupy it.

Ultimately, two contenders emerged out of a group of thirteen: Robert the Bruce's grandfather and John Balliol, lord of Galloway. Balliol was crowned king in 1292, but the move wasn't without controversy. He only reigned for three years before a council of twelve took over governing Scotland and, per the BBC, asked English king Edward I to mediate. Edward took the opportunity to move in and, when he finally invaded Scotland in 1296, Bruce took his side against Balliol. But this potentially controversial turn worked out, at least politically speaking, for the Bruces. Despite some support amongst Scottish people who recognized his coronation, Balliol eventually abdicated, creating a path to kingship for Robert. But Bruce wouldn't get there yet, at least not without some serious bloodshed first.

England tried to dominate Scotland

Scotland's neighbor to the south had seemingly had designs on the kingdom for years. According to the World History Encyclopedia, John Balliol was little more than a puppet king who was effectively chosen by Edward I of England. Now, things were already pretty tangled, given that nobles from both sides had intermarried for a while. But Edward had taken it one step further and went about his business with the assumption that Scotland was more of a sub-kingdom of his than an independent nation. Ostensibly, Balliol won the king contest because he was a closer relation to the royal line than the Bruces. Yet, it could also be because Edward saw him as a far more manageable subject who would fall into line.

Eventually, however, the council that took power away from Balliol attempted to side Scotland with France and create what was eventually known as the "Auld Alliance." For whatever power he still had at that point, Balliol sided with them in 1296 and denied Edward. Surprisingly, however, the complicated and ever-shifting web of alliances meant that Robert and the rest of his family actually sided with the English, at least in this skirmish. Eventually, Balliol was off the throne and in the Tower of London, though Britannica notes that the pope later stepped in and John was able to leave for Normandy, France.

Edward I's attempt to take Scotland

With Balliol out of the way, Edward I set about moving into Scotland. Per the World History Encyclopedia, his response to the "Auld Alliance" between Scotland and France was to wreak havoc via various battles and massacres.

Yet the Scottish weren't about to let things go so easily. While Robert Bruce would eventually take over, he took part in and was preceded by a number of rebellions, including one particularly powerful one led by William Wallace. Wallace, whom the BBC notes was born into an upper class family in Scotland, emerged on the scene in 1297 with his attack on the Scottish town Lanark and the subsequent killing of the settlement's English sheriff. Wallace became something of a lightning rod, attracting more and more discontented Scottish people and eventually leading a full-blown rebellion against the occupying English forces.

The greatest achievement of his fighting was arguably the Battle of Stirling Bridge, which began to loosen the English grip on Scotland. Robert was then one of Wallace's leading supporters, though he would also begin diplomatic negotiations with Edward while Wallace was overseas. As other Scottish leaders began to talk with the English, Wallace was left out in the cold. Eventually, Edward I put a price on his head. Wallace was eventually captured in August 1305 and, in short order, was transported to London and executed there.

Robert the Bruce's reign began with a bloody assassination

By the early 1300s, with Balliol gone and William Wallace brutally executed, it may have seemed like there was little between the Bruces and the throne. Except for John Comyn. Comyn was from a noble Scottish family not unlike that of Robert Bruce, per Undiscovered Scotland. Not only was his father one of the earlier contenders for the throne, but his mother was Eleanor Balliol — the very sister of the deposed and imprisoned John Balliol. Comyn himself would become a Guardian of Scotland after William Wallace resigned the post, which was a considerable political position to have at the time.

All of this meant that Comyn and Bruce were well established as political rivals. And, given that the path to the Scottish throne was closing yet again, both emerged as top contenders. To that end, on February 10, 1306, the two men met at Dumfries priory, as Smithsonian Magazine reports. Though it was apparently meant to be some sort of peacemaking meeting, things deteriorated dramatically and Bruce struck Comyn. He retreated but, upon learning that Comyn had been wounded, some of Bruce's supporters came back and murdered Comyn in the church.

English sources claimed it was "outrageous sacrilege," while another commentator called Bruce a "tyrant." Whether it was Robert or his followers that should take the blame, this led to his ascension to the throne, a deeply sullied reputation, and a relatively swift excommunication courtesy of Pope Clement V.

Robert the Bruce's early kingship harmed his family

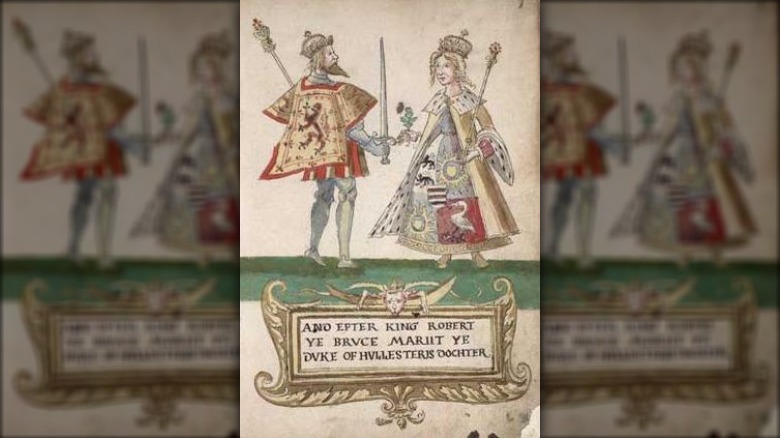

In the aftermath of Comyn's murder, Robert the Bruce took on a more aggressive stance with the English. Smithsonian Magazine notes that Bruce threatened to "defend himself with the longest stick that he had" if Edward wouldn't back off. Between that display of force and Comyn's bloody end, Bruce seemed pretty well motivated to go ahead and make himself king. He was crowned on March 25, 1306, though Edward had already made away with Scottish coronation artifacts like the Stone of Scone.

Unsurprisingly, things continued to be pretty rough not just for Robert, but for quite a few other members of his family. The early years of his reign were fraught with military defeats and pursuit by the English, to the point where he was nicknamed "King Hob" — essentially "King Nobody." At certain points, he even went on the run, hiding from the English.

But you may well have still preferred to be Robert himself, considering what happened to some of his siblings when the English went after them. The World History Encyclopedia reports that three of Robert's brothers were killed. And, according to Historic UK, things were pretty awful for the Bruce women, too. His 12-year-old daughter, Marjorie almost faced serious punishment at the Tower of London, but then was sent as a prisoner to a convent. Robert's sister, Mary, was reportedly locked in a cage hanging off the walls of a castle and publicly humiliated.

The Battle of Bannockburn was a turning point

Things may have looked pretty unsteady by 1314, a series of events began to turn things around for Robert. For one, Edward I had died in 1307, leaving his rather less fearsome son, Edward II, to continue the English assault against Scotland. As a result, English control in Scotland began to slip. According to Britannica, it got so bad that, in 1314, only one English stronghold remained in all of Scotland: Stirling Castle.

Robert the Bruce's forces besieged the castle that summer, but Edward II sent an estimated 13,000 soldiers, accompanied by further numbers of archers and horse-mounted cavalry, to relieve those trapped within Stirling Castle. Yet, though the 7,000 or so of Bruce's fighters were outnumbered, the Scottish made smart use of the landscape and dug anti cavalry ditches around Stirling Castle that helped to win the day. It also helped that relief forces for the Scots arrived later on. Perhaps most dramatically, it's said that Robert himself waded into the battle, personally killing a knight with a battle axe

All told, the English suffered considerable losses numbering in the thousands. The victory at Bannockburn shored up the kingdom and finally made it seem as if Scotland really could stand on its own. What's more, it seems to have finally legitimized Robert the Bruce for many, at least in the eyes of later historians, poets, and commentators who retold the tale (via Smithsonian Magazine).

Robert the Bruce got bold after Bannockburn

Whether or not the victory at Bannockburn fully redeemed Robert the Bruce after his bloody path to the throne, it certainly seems to have lent him a sense of power and added determination. In the years after the battle, says the World History Encyclopedia, Bruce sent some of his family members across the seas to take Irish lands and establish a base to the west.

His brother Edward was crowned king of Ireland in 1316, supported in part by locals who weren't especially happy at dealing with previous English overlords. Then again, it wasn't an especially successful move, given that Edward was killed on the battlefield just two years later. The Bruce family's designs on Ireland seem to have ended there.

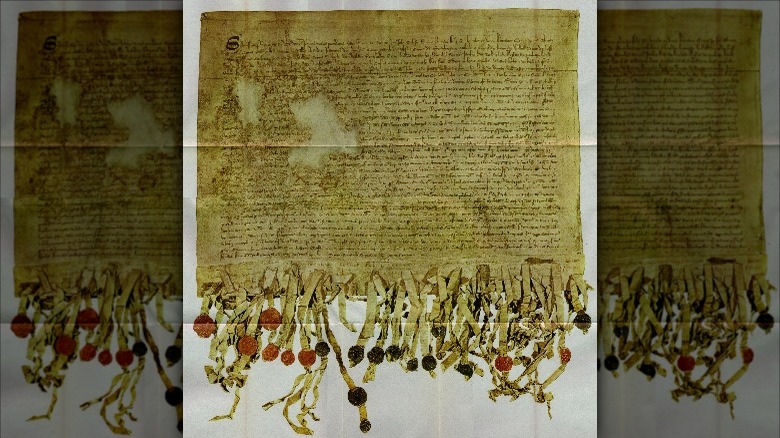

More enduring, perhaps, was the 1320 letter Robert Bruce sent to the pope petitioning for his own excommunication to be rescinded and for him to be officially recognized as Scotland's king. This "Declaration of Arbroath" also declared that Scotland was an independent kingdom, according to the National Records of Scotland. Given the language of the declaration, "bold" is certainly the right word. "As long as but a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be brought under English rule," the Declaration says. "It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honors, that we are fighting, but for freedom – for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself."

Robert the Bruce's crown was heavy

Things were surely more stable for Robert the Bruce in the years following the Battle of Bannockburn and the Declaration of Arbroath, though the National Records of Scotland notes that the pope didn't get around to recognizing Scotland's independence until eight years later.

Yet, things weren't all well in the Scottish kingdom. There's evidence of one failed assassination plot against Robert the Bruce, says the World History Encyclopedia, as well as a half-hearted English invasion that went nowhere. Yet, National Museums Scotland points out that artifacts from the kingdom, like Robert's royal seal, sometimes show him in a combative pose. On the seal, he's sitting atop a horse, clad in armor and raising a sword, perhaps ready to fight for his legitimacy and against the English.

Bruce did, however, make peace with England in 1327 after yet another king took over the throne there. Edward III, who gained the crown after the English deposed his highly unpopular father, agreed to renounce all claims to Scotland (via BBC). Though, as history so often shows us, things between the two nations wouldn't be entirely peaceful for the rest of time, Robert, his supporters, and many others in Scotland surely must have felt an immense sense of accomplishment and perhaps even relief at this news.

Robert the Bruce did not die of leprosy

Viewers who paid close attention to the details of 1995's quasi-historical film epic "Braveheart" may have picked up on a persistent rumor about Robert the Bruce. In the movie, he's forced to deal with his ailing noble father, who also happens to be suffering from leprosy, an affliction that's now known as Hansen's disease. Per the CDC, Hansen's disease is a bacterial infection that, if it's left untreated, can lead to serious nerve damage, blindness, and disfigurement. It's easily treated today but was once a sickness that caused great fear throughout history. Medieval people were especially afraid of this degenerative and then poorly understood disease.

In the film, Robert's father is shown to be suffering more and more from the progression of leprosy, which limits him from achieving the sort of power that he wants and therefore pushes his ambitions onto his own son. This harkens to the historical rumor that Robert the Bruce himself suffered from leprosy, which ultimately killed him in 1329.

Only, that's not right at all. Though no one's sure what illness ended his life, History Extra reports that it's pretty certain that it wasn't leprosy. No accounts from the time indicate that he had any of the common symptoms of the disease. He did suffer from declining health for years before his death, including episodes of serious illness that may have been linked to a neurological condition, but none of them link to leprosy.

Robert the Bruce is still linked to Scotland's independence

Though the retreat of the English in the 14th century finally marked Scotland out as an independent kingdom and the end of the Wars of Independence that had been part of its history, that sort of independence wouldn't quite last to the present day. For one, the ascension of James VI and I of Scotland and England to the English throne in 1603 (via Britannica) effectively united the two kingdoms under a single monarch, though they were still technically different lands. Later on, reports the BBC, the 1707 Acts of Union folded Scotland into Great Britain (Wales and Cornwall had been taken over back in the 16th century).

That doesn't mean the Acts were popular or that the union itself was able to avoid continual challenges over the centuries. Even today, Scottish independence is still a hot topic that routinely comes up for a vote and has most recently failed by a somewhat small margin, reports the New Yorker. Bruce's own Declaration of Arbroath is still amongst many symbols of Scotland's modern independence movement, and one that's cared for meticulously by archivists monitoring both climate control and security for the centuries-old document.