The Scholars Who First Translated The Bible Into English

Today, many versions of the Bible exist in English. But for centuries, the ability to read the Bible was only in the hands of the educated few who were literate and understood Latin. In Medieval England, the church acted as arbiters of what their members learned about the Bible and offered up its own interpretations of God's teachings. This was not a time of religious tolerance. In fact, anyone who opposed or questioned the church faced being labeled a heretic (via English Heritage). And the church often dealt out vicious punishments to heretics.

Risking their own lives, some learned scholars stepped up to make the Bible more widely accessible. John Wycliffe and later William Tyndale, who lived in different times in English history, used their incredible language skills to create English translations of the Bible. Both men made discoveries about what they saw as differences between the church's teachings and the actual text of the Bible. Wycliffe became an outspoken critic of the church, while Tyndale paid the ultimate price for his work.

John Wycliffe was a popular theologian and church critic

Born around 1330, theologian John Wycliffe studied at Oxford University (via Britannica). His education was frequently interrupted by outbreaks of the Black Death, as the bubonic plague was called, and it took him more than two decades to complete his doctorate degree in 1372 (via Christianity Today). By this time, Wycliffe was known as one of the university's brightest theologians.

Wycliffe left academia two years later to serve as a rector in Lutterworth. He soon began challenging the Catholic Church when he met with representatives of the pope as part of a royal commission. He questioned why the English paid papal taxes when the church was already wealthy, and believed that wealth contradicted the teachings of Christ. He felt that the money would be better used in England. Wycliffe soon found himself on the wrong side of Pope Gregory XI. The pope had Wycliffe called for his arrest, but his popularity in England spared him from harm. He did, however, agree to live at Oxford under a type of house arrest.

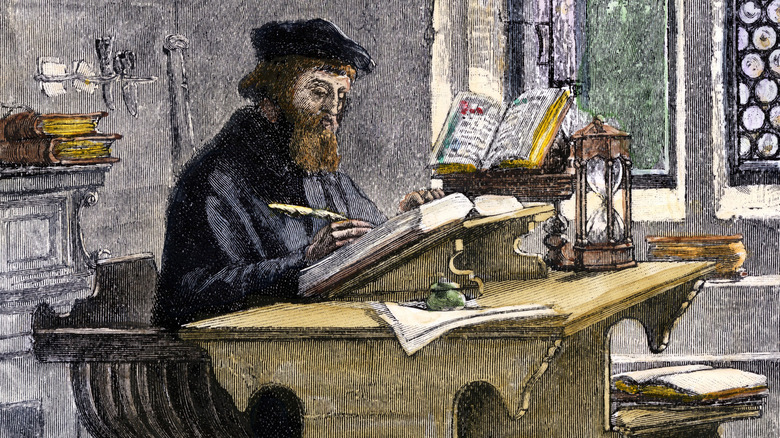

Wycliffe continued to criticize the church, disputing priests' ability to transform wine and bread into the body and blood of Christ during Mass (via English Heritage). He also believed that the scripture was the ultimate religious authority, not the church. In 1380, Wycliffe began his most dangerous challenge to the church by working on a translation of the Bible into English.

John Wycliffe declared a heretic after death

Wycliffe worked on his translation of the Bible with the help of John Purvey, according to Christianity Today. He wanted to make the word of God available to everyone: "Englishmen learn Christ's law best in English. Moses heard God's law in his own tongue; so did Christ's apostles." The church was none too pleased about this project.

Sadly, Wycliffe wasn't able to finish his translation of the Bible. He had a stroke in 1382 and a second one two years later, according to the Christian History Institute. Wycliffe died on December 31, 1384. His friend Purvey ended up completing the version of the Bible we now associate with Wycliffe, and Wycliffe's Bible and his other religious writings inspired a group of followers known as the Lollards (the name means "mumblers").

Perhaps the strangest twist in the story of Wycliffe's Bible happened after his death. A special religious group known as the Council of Constance met to unify the Catholic Church and to discuss the works of Wycliffe and another religious reformer, Jan Hus (also via Britannica). Wycliffe was posthumously found guilty of 267 counts of heresy in 1415. That apparently wasn't enough punishment for the church. Wycliffe's body was unearthed and burned by order of the pope. His ashes were tossed into a river.

William Tyndale wanted everyone to have access to the Bible

Following in Wycliffe's footsteps, William Tyndale was also a religious revolutionary. He shared Wycliffe's radical idea about making the Bible accessible to the common people, but Tyndale's efforts cost him his life.

He was born in Gloucestershire, England, in 1494, and he was raised Catholic, according to the Tudor Society. At the time, all Bibles were printed in Latin and all religious services were conducted in Latin as well. This meant that the average person, who only spoke English, had no direct understanding of the Bible and its teachings.

A bright student, Tyndale went to Magdalen Hall in Oxford for his education when he was only 12 years old (via the Friends of Tyndale House). There he displayed a gift for languages and sought to study the Bible for himself. Through his studies, Tyndale saw some disparities between the teachings of the church and the text of the Bible. After his time at Oxford, he went to Cambridge University, where he was a professor of Greek. In 1521, Tyndale left the academic world to pursue a life of religious service, becoming a chaplain. He developed an interest in creating an English-language version of the Bible, inspired in part by Protestant reformer Martin Luther, who translated the Bible into German. Tyndale asked the Bishop of London for his support with the project, but the bishop refused.

William Tyndale's translation of the Bible caused controversy

Instead of abandoning his English translation of the Bible, Tyndale fled the country to work on it. In 1524 he moved to Europe, where he devoted his time to his labors (via the Tyndale Society). Tyndale also met with one of his great influences, Martin Luther, while living abroad (via the Friends of Tyndale House). Tyndale produced a translation of the New Testament from the original Greek, but he soon ran into another hurdle: He had to find someone to print it. He managed to get his work published in 1526, and copies of his New Testament were smuggled into England. The Church vehemently objected to Tyndale's translation, and copies of the book were gathered up and burned near St. Paul's Cathedral in London.

In 1529, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, a leading figure in the English Catholic Church, declared Tyndale a heretic. During this era, being a heretic was a serious crime that could result in a death sentence. Tyndale stayed away from England, choosing to remain in hiding in Europe. He continued his translations and learned Hebrew so that he could work on the books of the Old Testament.

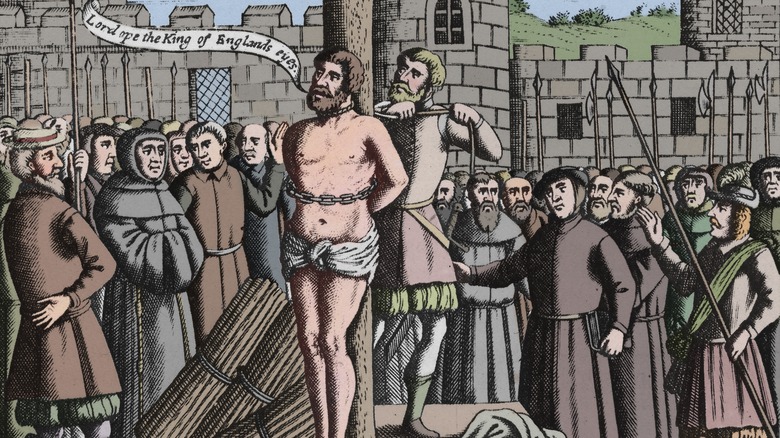

William Tyndale executed for heresy

Tyndale might have been able to complete his ambitious project had he not been betrayed by someone he thought shared his views. Living in Antwerp at the time, he met up with another Oxford graduate, Henry Phillips (via the Tudor Society). Tyndale believed that Phillips was an ally, but Phillips was actually working undercover to help capture him. Phillips asked Tyndale to go out for a meal, but he simply aided in getting Tyndale arrested. Tyndale was taken to Vilvoorde Castle in Brussels, where he was held prisoner for months.

While a prisoner, Tyndale requested a Hebrew Bible, dictionary, and grammar text because he wanted to "pass my time in study" (via The New York Times). He was eventually convicted of heresy and sentenced to death. His final words were reportedly "Lord! Open the King of England's eyes!" Tyndale was strangled to death, and then his body was burned at the stake in October 1536. Two years later, King Henry VIII ordered an English language edition of the Bible be made, and Myles Coverdale relied heavily on Tyndale's translations for his own version.

While Tyndale never completed his translation of the Bible, his work continues to live on to this day. It is believed that about 80% of the King James Bible comes from Tyndale's translation.