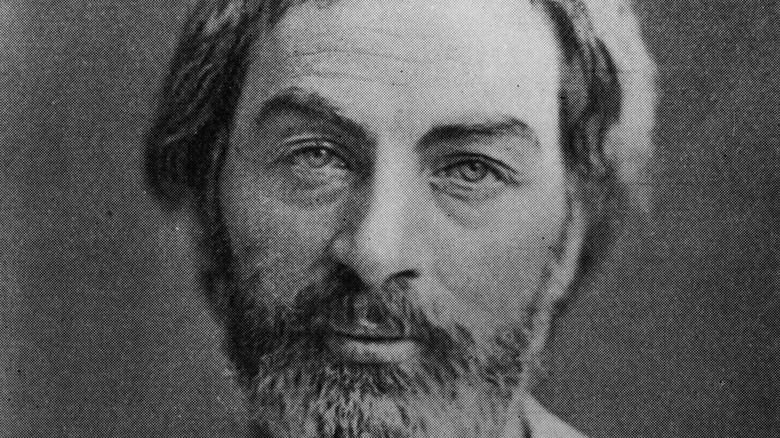

The Untold Truth Of Walt Whitman

The life of the man many believe to be America's greatest poet is not a simple rags-to-riches story; rather, Walt Whitman may be considered a continually marginal figure, who is still in the process of being recovered and reinterpreted for the modern age. The difficulty of Whitman is that he is both irresistibly modern — he created what we may consider "modern" poetic form — and historically distant.

In "An Old Man's Rejoinder," an essay reflecting on the composition and life-long alteration of his famous collection, "Leaves of Grass," Whitman claimed: "No great poem or other literary or artistic work of any scope, old or new, can be essentially considered without weighing first the age, politics (or want of politics) and aim, visible forms, unseen soul and current times, out of the midst of which it rises and is formulated" (via The New York Times). But to really come to grips with Whitman, it is also necessary to explore the singular life of one of the 19th century's most surprising and complicated figures, whose true nature is still being debated by academics to this day.

But how did a working-class child who, according to Biography, was forced by his father to leave school at 11 to help the family make ends meet emerge from poverty to be considered America's all-time finest poet? And why do readers still find him so intriguing?

Walt Whitman's caustic journalism

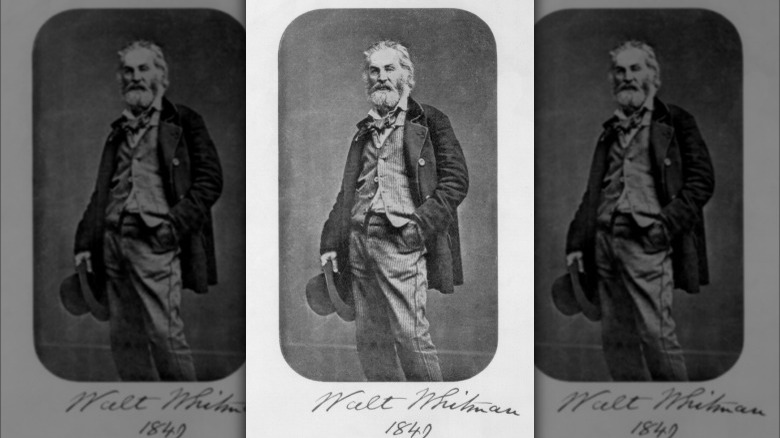

Walt Whitman left school at an incredibly early age. By the age of 12, he had taken his first job as an assistant printer for the Long Island Patriot newspaper, according to Literary Hub. The position set Whitman on a path toward a career as a journalist; he was being published widely by the tender age of 16.

The traditional image of Whitman is that of a benevolent and inclusive "poet of democracy," whose sensuality arises from an all-consuming love of humanity. But as his early writing demonstrates, the great poet also had an acerbic side, which he flexed in his plethora of articles, editorials, and essays. Whitman sometimes used his editorial powers to unleash bombshells about other writers, discrediting their work or highlighting their rehashes of previous writing, under titles such as "The Great Bamboozle! — A Plot Discovered!" (via The Walt Whitman Archive). Literary Hub reports that Whitman even published anonymous praise for his own poetical works, a practice that would go against modern standards of journalism.

However, Whitman never considered himself to be a natural journalist, despite all the years that the job supported him: "My opinions are all, always, so hazy — so slow to come ... I am no use in any situation which calls for [an] instant decision," he later wrote about that time (via Literary Hub). Despite this, even after he had become a fully-fledged poet, Whitman continued to publish numerous articles and essays up until his death in 1892.

Walt Whitman struggled for recognition

We might be tempted to think of Whitman's star power being felt in his lifetime, and that "Leaves of Grass," Whitman's masterpiece, was understood for its genius from its very first print run. But the fact was, Whitman's poetry was considered both a commercial and critical failure for much of his adult life.

According to Biography, the poet first printed "Leaves of Grass" at his own expense, and while the collection received some notable praise — not least from Ralph Waldo Emerson — sales were poor and critical reception of his highly experimental style of free verse was little appreciated by contemporary readers and critics. According to Vox, by the time he was 39 Whitman was back living with his mother, jobless and near penniless, despite his long career as a newspaperman and his "Leaves of Grass" having been published twice.

It took a number of years for him to find success as a poet. Only after "Leaves of Grass" had already gone through multiple editions, with Whitman fleshing out the collection with more and more material, was his poetry taken seriously by a broad audience, and he could enjoy its financial rewards.

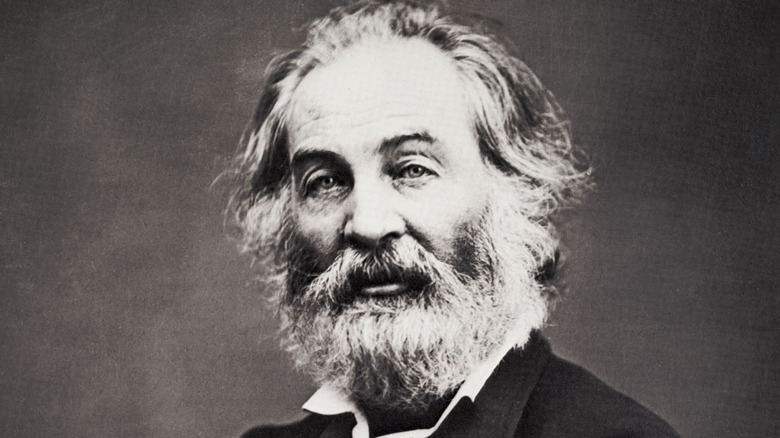

Walt Whitman's sexuality

Few poets have attracted as much heated debate over the nature of their sexuality as Walt Whitman.

"Leaves of Grass" began to grow in notoriety following the release of its third edition in 1860, which saw the inclusion of two new sections, according to Biography. The first, "Children of Adam," was notable for its heterosexual erotic overtones, while another, known as "Calamus," openly portrayed sensual relationships between men that were undeniably homoerotic. This was groundbreaking work, but not everyone in the 19th century appreciated Whitman's candor, while even the earlier editions of "Leaves of Grass" attracted the ire of contemporary critics who reviled Whitman's poetry as "a mass of stupid filth" and "a rotten garbage of licentious thoughts" (via Boston Review).

One of the most famous anecdotes used to cast light on Whitman's romantic life concerns the writer and gay icon Oscar Wilde, who, after meeting Whitman in 1882 told the activist George Cecil Ives that he was certain of Whitman's homosexuality, as Wilde had "the kiss of Walt Whitman still on my lips," according to Bi.org.

The same source states that Whitman is believed to have been in an intense relationship with a bus conductor named Peter Doyle, though there is no evidence to say categorically that their love was sexual in nature. When asked directly about his sexuality, Whitman often obfuscated; in one letter, he described having fathered six illegitimate children with multiple women, though no researchers have ever unearthed whether these people actually existed (via Bi.org).

Whitman's inconsistent views on race

Whitman's poetic sensuality is typically taken by readers as part of the poet's overall preoccupation with individual freedom, which, one might assume, would also make him an out-and-out opponent of one of the 19th century's most abhorrent practices: slavery.

As claimed by The Conversation, Whitman did sometimes voice his opposition to slavery. The poet was reportedly horrified by the sight of public slave auctions, and lost his job as a journalist at the Brooklyn Eagle as a result of his beliefs. Immediately afterwards, he co-founded the Brooklyn Freeman, a newspaper in support of the "Free Soil" movement.

But as Ohio History Central explains, although such a movement opposed the expansion of slavery into more American states, free soilers fell short of calling for the abolition of slavery, with Whitman considering activists calling for such political "extremists," per PBS. Despite his views on individual freedom and his writing about the plight of slaves, Whitman was unfortunately not so visionary as to reject the racism typical of his age. The poet's racist comments continue to shock and disappoint readers discovering his "poetry of democracy" today (via Jstor).

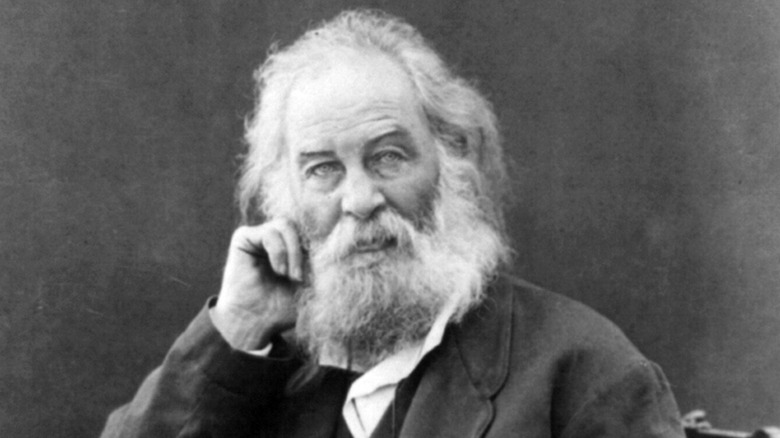

Walt Whitman's personal tragedies

As noted by Biography, the home life of Walt Whitman was a difficult one for many years. Whitman's father had run the once financially solvent family into the ground while Whitman was young, and upon his father's death in 1855, Whitman became the head of a family struggling with debt and addiction. Two of Whitman's four brothers suffered from alcoholism; his older brother, Jesse, was institutionalized as a result. Whitman slept in the attic of the family's Long Island home and still had to share a bed with his brother, Edward, who was mentally disabled (per The Walt Whitman Archive).

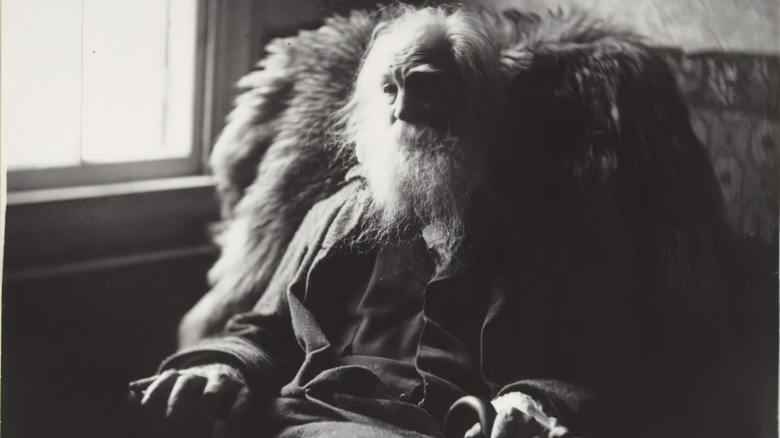

According to Biography, in 1873 Whitman's life was turned upside down following a stroke which left the poet partially paralyzed and which would affect him for the last two decades of his life. Nevertheless, Whitman continued to write, and to revise "Leaves of Grass," with what scholars refer to as the ninth "Deathbed Edition" released in 1891-2, per World Digital Library. Whitman died March 26, 1892, aged 72.

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).