Why MKUltra's Top Brainwashing Scientist Was A Real-Life Nightmare

One of the weirdest chapters in U.S. history was approved on April 13, 1953, and any time anyone says anything about "the good ol' days," when things were just better, simpler, and kinder, well, point to MKUltra and say, "Check out this madness!" When then-CIA director Stansfield Turner testified about the program in 1977, he said (via the Smithsonian) that the bottom line was to develop "the use of biological and chemical materials in altering human behavior." That's absolutely the stuff of a terrifying Netflix horror series, but it was very real — and it destroyed an unknown number of lives.

Operating under the umbrella of MKUltra were as many as 162 sub-projects, with as many as 80 different organizations involved in research. Unfortunately, a lot of what went on within them has been lost: In 1973, the majority of the documents associated with MKUltra were destroyed in a massive (and not-at-all-suspicious) purge.

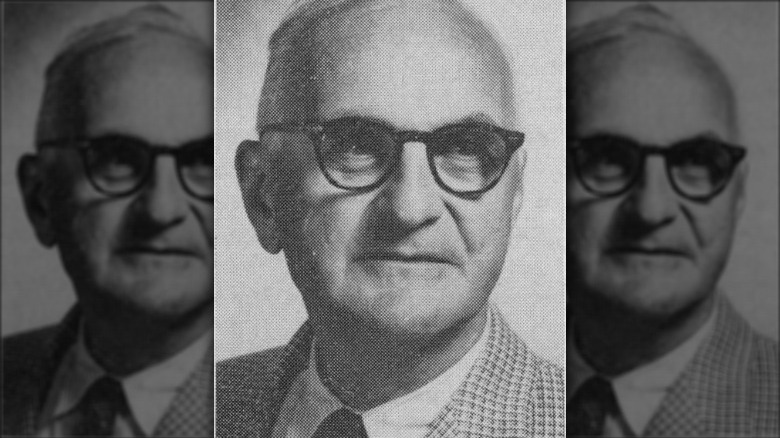

Traces of some survived, including documentation on Sub-project 42 — also known as Operation Midnight Climax — and sub-project 68. That, says McGill University, was the work of Dr. Donald Ewen Cameron, a psychiatrist who performed experiments so horrifying he's been called "Scotland's Mengele." Being compared to the Nazi's most notorious doctor probably isn't the life goal of most medical professionals, so let's look at what he did to deserve this dubious title.

The work of Dr. Donald Hebb

Canada's McGill University has owned up to the part it played in MKUltra's Sub-project 68, and they say that it really started before Dr. Ewen Cameron even got involved. In 1951 — a few years before the U.S. government and the CIA approved MKUltra — there was a top secret meeting held at Montreal's Ritz-Carlton. It was the start of a series of experiments backed by the British, the Americans, and the Canadians, and they wanted to know what prolonged sensory deprivation actually did to a person.

That right there is getting into some shady territory, but the promise of a $10,000 grant — the equivalent of just over $100,000 today — had to be pretty tempting. McGill's then-director of psychology, Dr. Donald Hebb, took the money and set up experiments using his ready-and-waiting pool of test subjects: students.

Hebb — who did pay the students for their participation — basically put them in a room for 24 hours, in a set-up that deprived them of all sensory input. Results were telling: They became super sensitive to the sensory stimuli they did receive, and then, things started getting really weird. He reported that "the subject's very identity had begun to disintegrate," and that's when someone should, ya know, stop. Hebb submitted his findings to the CIA, and it ended up being just the beginning.

MKUltra found their doctor

The CBC says the CIA recruited Dr. Ewen Cameron a few years into MKUltra, using the Society for the Investigation of Human Ecology to approach Cameron and tell him that he really, really needed to apply for one of their grants. He did — and he got it.

According to The Washington Post, Cameron was recruited in 1957, and he was a big deal. His list of credentials was so long it's impossible to list them all, but for starters, his resume included the University of Glasgow and Johns Hopkins, and in the 1930s, he was lauded for setting up a series of psychiatric clinics. When it came time to evaluate Nazi leaders ahead of the Nuremberg Trials, he was one of a group of internationally renowned mental health professionals who were sent to decide just what was going on in the heads of some of the worst war criminals the world had ever seen.

His work had led him to the belief that mental illness could be "cured" like, say, a broken hip might be rehabilitated. While guys like Freud encouraged talking through problems, Cameron thought things like electroshock therapy and drug cocktails could be used to physically change the brain and get rid of the illness in question. Sounds questionable? Joseph Rauh Jr. was one of the attorneys that represented the group who filed lawsuits in the mid-1980s. He didn't pull punches, saying, "We hanged Nazis for doing the sort of things Cameron did."

Depatterning and psychic driving

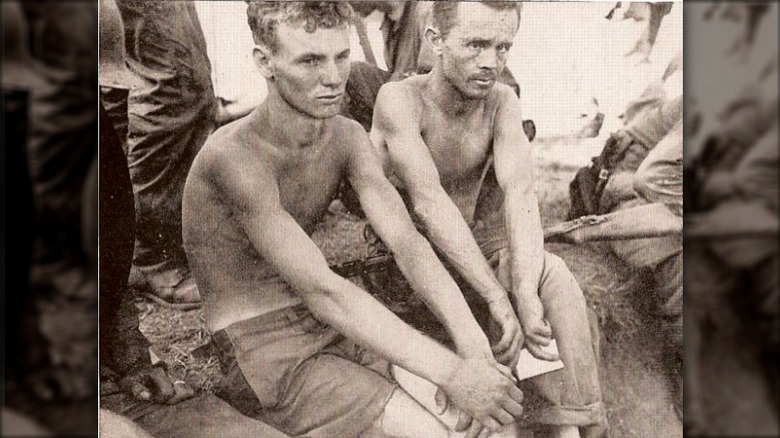

At the heart of MKUltra, says The Guardian, was the broadcasting of videos of American POWs from the Korean War condemning their own country and lauding the benefits of Communism. The U.S. wanted to know just how such a thing could possibly happen, and Dr. Ewen Cameron had a theory: brainwashing. He wanted to know if it was possible to wipe a person's mind and reinstall a new personality. Don't worry, it gets worse.

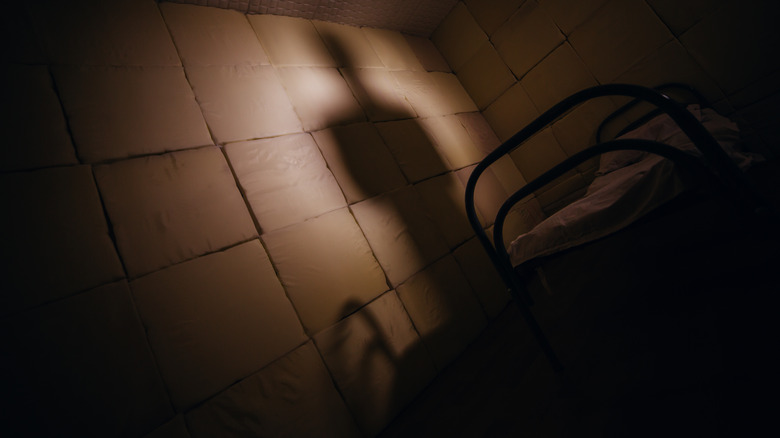

The idea was to first "depattern" the person in question. He tried a variety of things, including multiple electroshock therapy sessions a day and massive doses of drugs — including LSD. Many spent this period of time in what he called the "sleep room," where they were drugged into a medically-induced coma that they were brought out of only to be given three meals a day and the occasional trip to the bathroom.

The goal, says CBC, was to reduce the patient to what was called a "childlike state," with some people destroyed so completely that they could no longer walk, talk, or dress themselves Shoelaces? Those were right out. The idea was turning the mind into a fresh slate for the next part of the process, called "psychic driving."

Patients protested

The second part of the technique was inspired by something called the Cerebrophone, which was essentially a "learn-while-you-sleep" recording device. His version was a continuous-loop cassette player that would deliver messages on repeat ... and it's even worse than it sounds.

According to The Guardian, it started with playing tapes designed to tap into the reason the patient sought help in the first place. These negative statements were sometimes taken from the therapy sessions Cameron conducted when patients first arrived, says Rebecca Lemov, author of "Brainwashing's Avatar: The Curious Career of Dr. Ewen Cameron." He had various people record the tapes — sometimes including the patient's loved ones — and it was, on the whole, incredibly traumatizing. That could be heightened with various drugs, eventually was replaced by positive messages, and the so-called "psychic driving" would continue.

Cameron quickly found patients didn't want to listen to the messages. He first solved the problem by wiring the speakers into football helmets and locking them onto patients' heads, but that ended up being not ideal. Some would bang their heads against the walls relentlessly, trying to get the helmets off — and that's when he realized he could just put them back into a medically-induced coma and play the tapes for as long as he wanted. Patients would be subjected to messages repeated hundreds of thousands of times, as they were kept in their coma for up to a month. Did it work? Take a guess.

Esther Schrier's story

It's not clear how many patients Dr. Ewen Cameron's treatments destroyed, but some families have come forward with stories of what was done to their loved ones. Esther Schrier — who was a nurse at Montreal's Jewish General Hospital — tragically lost her first child at just three weeks of age. The guilt of her baby's deadly staph infection stayed with her, and when she became pregnant with her second, and the CBC says she went into Cameron's care in February of 1960. In theory, he was supposed to help her anxiety, depression, and postpartum depression.

She went into the sleep room.

Pregnant with son Lloyd, Esther was kept in a drug-induced coma in the sleep room for a month, where she lost 13 pounds. On March 10, Cameron's notes read: "She is disoriented as to time only and is probably in her second stage of depatterning. There is no incontinence, there is no mutism, and we are continuing this intense treatment of her until we get complete depatterning."

On March 12, her records show she was considered "depatterned": She could no longer stand, speak, could barely swallow, was incontinent, and required treatment by an obstetrician for severe bleeding. Cameron's work stopped when she gave birth, and Lloyd remembered a broken mother. She had no idea how to boil water, much less care for a child. She very slowly recovered — mostly — and died in 2017. Lloyd has continued to fight for recognition, recompense, and an apology.

Jean Steel's experience

Jean Steel was another one of Cameron's patients, and — like the others — she didn't sign up to be a part of MKUltra, depatterning, or psychic driving at all. She was admitted to McGill's Allan Memorial Institute in 1957, needing help dealing with depression and the loss of her child.

The Guardian talked to Alison Steel, Jean's daughter and one of the many family members trying to shine a light on what was done to their loved ones without their consent. She said that at the time, Cameron was something of a celebrity. "He was this miracle psychiatrist," she said. "He was supposed to do wonders with people with depression or mental health issues." He did — technically, because nothing says "wonders" has to be a good thing.

Jean spent three months under Cameron's care, and spent two periods in a drug-induced coma. The first was for 18 days and the second for 29 days, all while hearing endless recorded messages and being subjected to a series of electroshock therapy sessions. Alison said that when her mother returned, it was no longer her mother. She said: "She wasn't able to talk to me about life and regular stuff. She wasn't able to joke and laugh ... She would blurt out something like: 'We must do the right thing!'" Alison believes those random phrases her mother would sometimes say were from the recordings that she'd been forced to listen to for hours.

From doctor to patient

In 1984, New Scientist reported on a lawsuit filed on behalf of some of the people who ended up a part of MKUltra's Sub-project 68. They stressed how they'd been unwilling participants, and that they'd gone to the institute for other issues. Velma Orlikow, for instance, was dealing with postpartum depression. Another patient was suffering from leg pains that no one had been able to diagnose. And Mary Morrow?

Dr. Morrow, says The Washington Post, had applied for a fellowship in psychiatry with Cameron. That was in December of 1959, and according to the lawsuit (via the Consumer Law Group), Cameron diagnosed Morrow as having "nervousness and tension." Instead of being considered for the fellowship, the neurologist was admitted to his Allan Memorial Institute, diagnosed with schizophrenia, and given such a heavy dose of barbiturates that it triggered an allergic reaction and she suffered from a prolonged loss of oxygen to the brain.

Morrow's family got involved, and it was only at their insistence that she was transferred to another hospital. She was left with permanent impairments: She was unable to recognize faces, had impaired spatial recognition, and lost a good portion of her memory. Her family sued, first based on the treatment alone, then again, after discovering she was a part of the MKUltra program. The lawsuits were dismissed, even though it was later shown there were a higher-than-usual number of people diagnosed with schizophrenia, presumably to increase Cameron's subject pool.

Automating mental health

According to "Brainwashing's Avatar: The Curious Career of Dr. Ewen Cameron," there was more to his work at the Allan Memorial Institute than just exploring the CIA's questions about brainwashing. He wanted to cure schizophrenia, and win a Nobel Prize for it.

Cameron also wanted to revolutionize the way psychology and psychiatry looked at mental illness. The idea that people needed to sit down and talk about their problems was the old way of doing things, and Cameron was living in an era where things were getting more and more automated. He saw no reason why psychiatry should be any different.

His goal was to standardize his treatment, and once he did it for schizophrenia, he believed he would open a "gateway through which we might pass into a new field of psychotherapeutic methods." Once it was down to an exact science — the precise number of hours in a coma, the number and duration of electroshock treatments, the exact dosages of drugs — he believed that curing mental illness could be as simple as admitting a patient, putting them through the program, and spitting out a brand new, problem-free person on the other side. It's safe to say that the exact opposite happened.

The end of the experiments

Dr. Ewen Cameron was an undeniably fascinating figure, and as horrible as his experiments were, the way people continued to talk about him was even more telling. Lloyd Schrier, son of Cameron patient Esther Schrier, told the CBC, "Oh, 'He was God-like,' they would say." According to "Brainwashing's Avatar: The Curious Career of Dr. Ewen Cameron," he left his position at Allan — and his patients — in 1964. Care of his patients went to his assistants, and here's where things get even weirder.

After he left, his position as chair of the department of psychiatry was handed to Robert Cleghorn. Cleghorn immediately went and took a long, hard look at what Cameron had actually been doing in his little corner of the university, and he was pretty shocked. Even as he wrote about Cameron's "warmth... [which was] never allowed to appear as intimacy," he wrote about a pretty big blind spot: Cameron had apparently hired a few assistants with "psychopathic personalities."

And that kind of explains why, when they were ordered to stop their depatterning and psychic driving of patients, they just sort of... didn't. Not, at least, until well into 1965, months after they were told to end the experiments.

What the people in charge thought

Cameron never got his Nobel Prize — in fact, he died not long after leaving Allan Memorial Institute. According to what his son, Duncan, told WBUR, it was 1967 when he decided to climb Street Mountain in the Adirondacks. A notoriously tough climb, he did it with his son James, and when he got to the top, he had a heart attack and died almost instantly.

By that time, information on Cameron's sleep room projects was coming out, and there were all kinds of people who were very quick to distance themselves from it. His successor at Allan, Robert Cleghorn, would later write (via "Brainwashing's Avatar: The Curious Career of Dr. Ewen Cameron," "Cameron's controversial practices [are] now thoroughly discredited." Donald Hebb — the psychiatrist who started the whole mess with his sensory deprivation experiments — had even less kind things to say: "Cameron was irresponsible — criminally stupid. Anyone with any appreciation of the complexity of the human mind would not expect that you could erase an adult mind and then add things back with this stupid psychic driving."

And what about the CIA, who had approved and funded the research in the first place? Cameron reported to John Gittinger, an agent in charge of overseeing parts of MKUltra. His response? "Now, that was a foolish mistake. We shouldn't have done it, I'm sorry we did it."

The missing documents

While more is known about the experiments of Dr. Ewen Cameron than about some of the other MKUltra projects, there's still a lot of information missing. Most of the patient files are gone, and according to WBUR, they weren't just misplaced, they were destroyed.

Duncan Cameron is Ewen Cameron's son, and when he speaks of his father, he talks about a man who loved to hike, read science fiction, and who had an obituary that read, in part: "Those who are privileged to know him, even briefly, will not soon forget the warmth and kindliness of this understanding man." They also asked him for clarification about what happened to his father's personal papers and patient records, and he replied, "Well, I didn't destroy the documents."

So, they went back to a 1983 court transcript, where Duncan was called to the stand to testify about what happened to his father's documents. After his mother confirmed that yes, there were 12 boxes of papers that her sons — both lawyers — said she probably shouldn't share, Duncan revealed that he had gone through and taken out "several papers" that identified "a particular patient." While he didn't name names or give specifics, he did say that papers "related to patients were destroyed."

The lawsuits

For years, the patients of Dr. Ewen Cameron — or, more accurately, the families of those patients — have been trying to get compensation for the unthinkable experiments their loved ones were subjected to. And they haven't been super successful.

The National Post reports that in 1992, 77 of Cameron's patients were awarded an ex gratia settlement of $100,000, and that's all well and good, but claims made by more than 250 other people were rejected for various reasons. In some cases, applicants couldn't prove the conditions they currently lived with were a direct result of what they went through at Allan, and in others, they were treated outside of the time frame.

That was the case for people like Phyllis Goldberg. Montreal's CTV says that by the time she died in 2011, she had spent the last 20 years of her life as an "infant," unable to allow anyone near her head without a terrible reaction. Her niece later said, "She had electric shock equipment put on her head so many times that it [remained] in her subconscious." Alison Steel won compensation for her mother's misery in 2017, says the CBC: $100,000 in exchange for ending legal action. She's the exception, though, and the CBC says that 2020 saw others — like Lana Ponting, who was just 16 when she was sent to the sleep room — hoping that year, it would finally be their year, thanks to a class action lawsuit filed in 2019.

Modern-day torture techniques

The work of Dr. Ewen Cameron may have been discredited by mainstream psychiatry, but that doesn't mean it went away completely. In 1963, the CIA published the Kubark Counterintelligence Interrogation manual, and that's exactly what it sounds like — guidelines on how to get people to talk. As the CBC notes, it's sourced pretty heavily from Cameron's work, and talks about things like "deprivation of sensory stimuli, threats and fear, pain, hypnosis and narcosis," and the source of their research? "A number of experiments at McGill University."

The manual got updated in 1980, but the techniques that have come about — including things like waterboarding and restraint in a "coffin-like wooden box" — still harken back to that original research. And it's still hugely controversial: In 2019, The New York Times published drawings done by prisoners who had been subjected to these torture methods at Guantanamo Bay, and it's not for the faint of heart.

In 2020, director Stephen Bennett released "Eminent Monsters," a film that examined the link between Cameron's work and the torture techniques used by organizations around the world, including the CIA. He told The Scotsman: "Cameron's entire focus seemed to shift after the Nuremberg Trials. ... The legacy can be seen in the torture techniques employed in Northern Ireland and in Guantanamo Bay."