12 Best Alexander Graham Bell Inventions

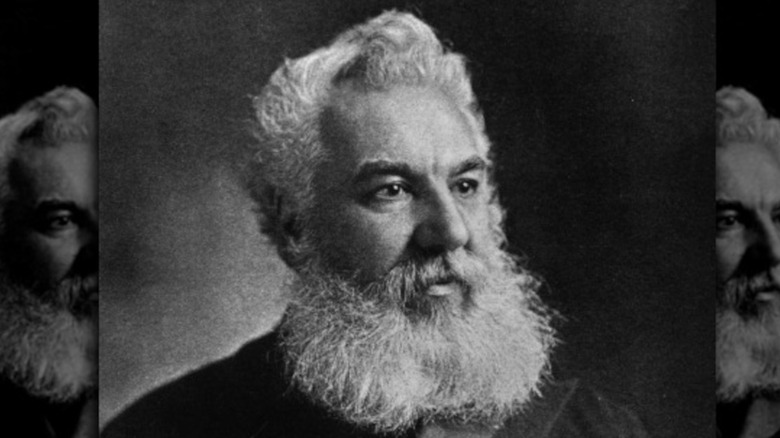

It's no stretch to say that the modern world would be very different if Alexander Graham Bell hadn't existed. While most people know that Bell is popularly credited with the invention of the telephone (he was actually one of several inventors working along similar lines, but won the race to a patent), his impact goes far beyond one appliance. He had a lifelong dedication to the deaf community (his mother and his wife were hearing impaired), and many of Bell's ideas stemmed from his desire to help the deaf. Among his achievements are the founding of what would eventually become one of the largest corporations in the world, AT&T, and the initial organization of the National Geographic Society.

The list of inventions credited to Bell is surprisingly long and varied. Like his peers Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla, Bell was interested in a wide variety of scientific phenomenon, and worked his entire life to perfect devices and concepts that would benefit mankind, often in ways he couldn't anticipate. While his legacy has been clouded by some of his beliefs that have not aged well at all, Bell remains one of the most important inventors in history. The telephone alone changed the course of society — but so did several of his other ideas. Here are the best Alexander Graham Bell inventions.

Wheat husker

Some people require time before their greatness is revealed. Others are obviously marked for great things from a very young age. Alexander Graham Bell falls into the latter category. For most of us, the closest we get to scientific immortality as children is winning a school science fair. But Bell was actually inventing cool, useful things.

"Alexander Graham Bell: Giving Voice to the World" explains that when Bell was just 12 years old, he often played with his friend Ben Herdman in a grain mill owned by Herdman's father. The two boys were frequently underfoot playing games, and finally Herdman's exasperated father challenged them to do something "useful," like removing the husks from wheat grain. This was a time consuming, manual process at the time.

"Alexander Graham Bell and the Telephone," reports that Herdman gave up on the task pretty quickly, but Bell's natural curiosity set in and he set to work figuring out how to make it easier and faster. After using a stiff brush to remove the husks from some grain, Bell realized the tool worked, but was much too slow. Bell attached brushes to the side of a metal bin with rotating paddles. The paddles pushed the grain against the brushes — an efficient, workable de-husking machine. Herdman's father used the invention for years afterward.

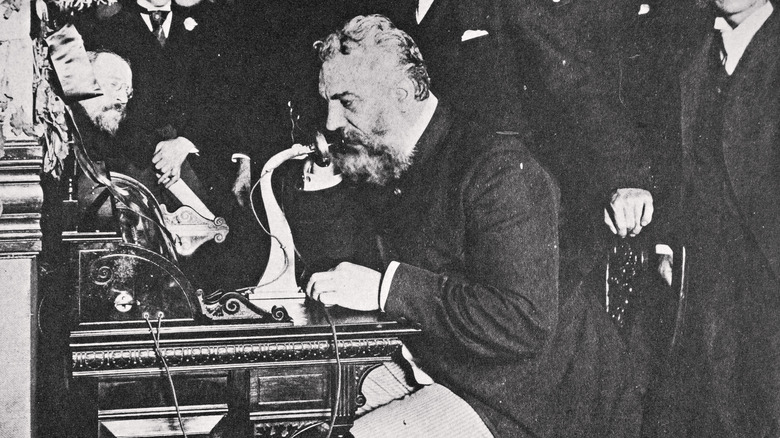

Telephone

Ironically, Alexander Graham Bell's most famous invention was also his least unique. History reports that both Antonio Meucci and Elisha Gray were working on technologies very similar to what Bell eventually unveiled as the telephone.

Bell's journey towards one of the most fundamental pieces of modern technology began in 1871. According to Interesting Engineering, a group of investors approached Bell about devising a harmonic telegraph — a telegraph system capable of sending multiple messages simultaneously over a single wire. Bell began work on the concept, but, Biography notes, he began to be distracted by another idea: transmitting the human voice over those same wires. Work on the harmonic telegraph slowed down so dramatically that the investors hired an electrician named Thomas Watson to work with Bell and get the project back on track. The two men proved to be an ideal partnership, and by 1876 Bell filed for a patent for the telephone.

But, as noted by the Library of Congress, Italian inventor Antonio Meucci had filed an announcement of an invention very similar to Bell's telephone in 1871, but ran out of funds before he could file a patent. And Bell just barely beat inventor Elisha Gray to the patent office — Bell's lawyer was the fifth entry on the patent office's list, and Gray's was 39th. If Gray's people had gotten there sooner, he might be remember as the father of the telephone instead of Bell.

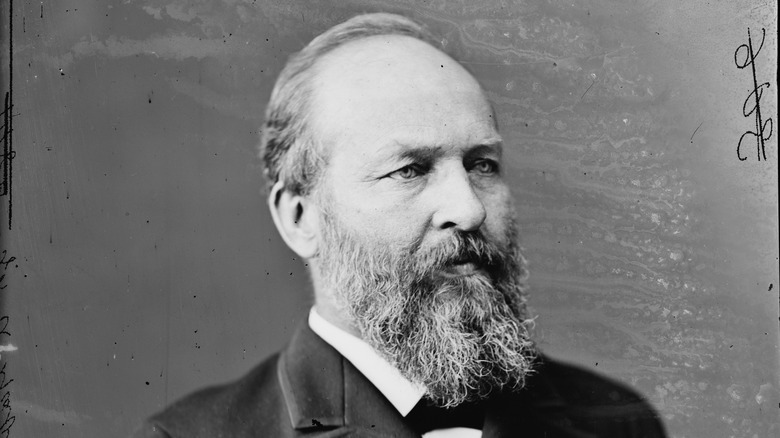

Metal detector

Being a world-famous inventor means that when national emergencies come up, you get called in to help. That's what happened in July 1881, when newly elected president James A. Garfield was shot in the back by Charles Guiteau. According to History, the injury should have been non-fatal, but the doctors who worked to assist Garfield couldn't locate the bullet and made things worse by probing the wound with non-sterile fingers and instruments.

When Alexander Graham Bell heard that doctors could not locate the bullet, he remembered an accidental discovery during his work on the telephone: a method of detecting metal using electricity (via HistoryNet). He immediately began working on what would be the world's first metal detector, and went to the White House twice to test it. Unfortunately, those tests failed — the results were probably muddied by the presence of metal wires in the president's mattress. Garfield soon died after weeks of excruciating suffering, mainly because of the infection introduced by his doctors.

However, Bell's failure with Garfield didn't deter him. He perfected his metal detector and demonstrated it for doctors (via Britannica). It was eventually adopted by surgeons around the world, and is credited with saving many lives during the early 20th century, most notably during the Boer War and World War I.

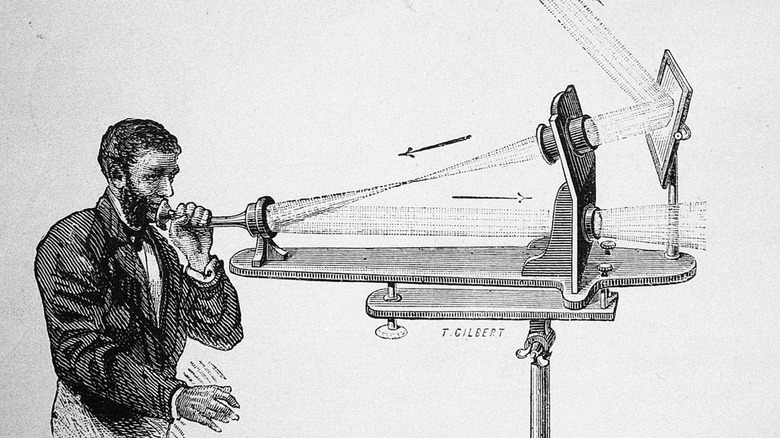

Photophone

It's easy to get excited by distinct inventions like the telephone, but much of the work done by inventors doesn't result in usable products. Instead, the value is often in the knowledge they contribute. That's the case with the invention that Alexander Graham Bell regarded as "the greatest invention I have ever made" — the photophone.

Invented shortly after his work on the telephone was complete, the photophone was another device for transmitting sound waves. But, as reported by Vice, the photophone didn't use wires or electricity. It used light. According to Inverse, Bell used selenium, a material that reacts to light in measurable ways, to create a wireless phone that used sunlight as a transmitting medium.

Incredibly, the contraption worked. In February, 1880, Bell was able to clearly hear his assistant, Charles Sumner Tainter, singing "Auld Lang Syne" over the photophone. Unfortunately, the phone didn't work well with the artificial light available at the time, so rainy days rendered it useless. Bell was never able to make the photophone work in a practical sense, but Britannica explains that Bell's work on it contributed to understanding of the photovoltaic effect, which is used in solar energy applications and elsewhere today.

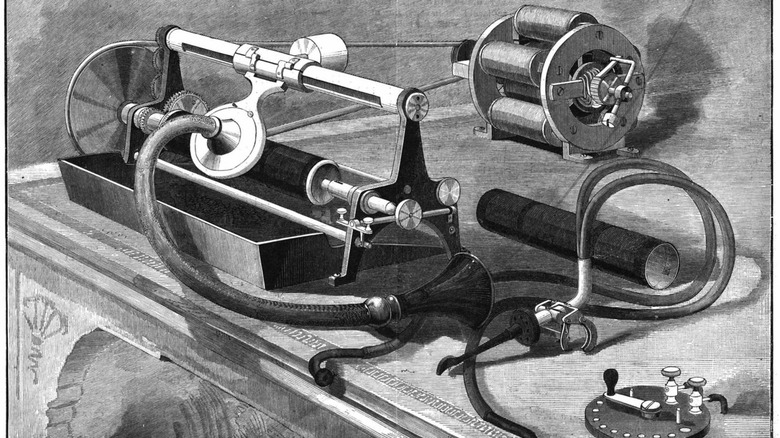

Graphophone

Because his family was involved in elocution and speech, and because he had family members who were deaf, Alexander Graham Bell spent much of his energy thinking about sound. In 1877, Thomas Edison invented the phonograph, but as Britannica explains, it was a delicate and unreliable piece of equipment. Edison seemed to lose interest in improving it, and Bell thought he could do better.

It took Bell five years, but he eventually came up with the graphophone. "The Beginner's Guide to Vinyl" reports the graphophone was a huge leap forward. It used wax instead of tinfoil, resulting in huge improvements in sound quality capabilities. The differences were enough to gain Bell a separate patent from Edison's invention. The graphophone led directly to the vinyl records that soon brought mass-produced recorded music to the world. Bell co-founded the Volta Graphophone Company in 1886, then sold it along with the patents to the American Graphophone Company, which eventually evolved into Columbia Records.

Incredibly, as noted by Interesting Engineering, Bell's work on the graphophone almost incidentally resulted in the development of the first working microphones. Prior to that, people had to shout very loudly to use any sort of electronic sound equipment.

Audiometer

Alexander Graham Bell was born into a family that took speech and hearing very seriously. As reported by A Noisy Planet, Bell's father, grandfather, and uncle all taught public speaking professionally, and both his mother and his wife were hearing impaired. This certainly influenced the energies he put into inventions that were connected to sound and hearing, such as the telephone and graphophone.

In fact, one of Bell's inventions, the audiometer, which tests hearing and helps determine levels of hearing loss, is still in use today. After the invention of the telephone, Bell needed a way to measure the audio levels of his device. The engineers assigned the task named the measurement the Bel in honor of their boss, which is why we measure sound in terms of decibels (one-tenth of a bel) today.

"Alexander Graham Bell: Making Connections" explains that the audiometer was the first invention that made detecting hearing problems possible in public schools. "Alexander Graham Bell: Giving Voice to the World" tells how Bell used his new invention to test the hearing of hundreds of children. Many who had been dismissed as lazy were found to have significant hearing loss, explaining their lack of attention in school. Bell's work on the audiometer undoubtedly changed the lives of many people as a result.

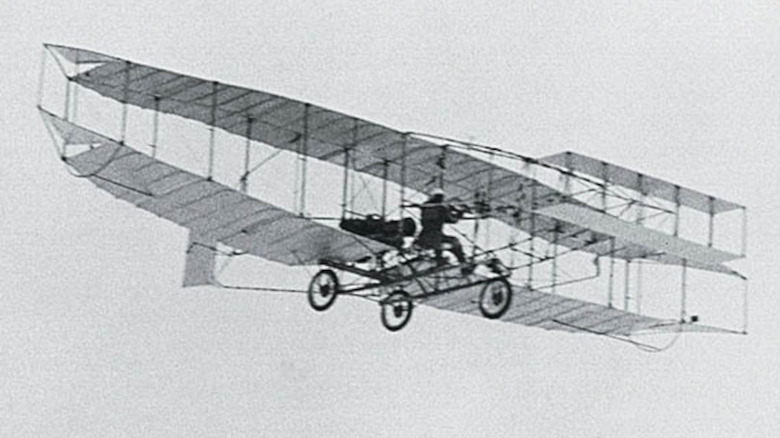

Silver Dart

Alexander Graham Bell wasn't the first person to get an aircraft off the ground, of course. The Wright Brothers managed that trick in 1903. But Bell contributed to the early development of flight in a huge way that's often overlooked today.

The Canadian Encyclopedia notes that Bell's interest in flight began when he was a young boy, but as reported by Britannica, Bell didn't begin serious began research into heavier-than-air flight until the 1890s — still long before the Wright Brothers' historic flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. According to the National Air Force Museum of Canada, Bell formed The Aerial Experiment Association (AEA) in 1907 with the specific goal of building a "practical" aircraft capable of carrying a pilot.

Under Bell's guidance, the AEA created several gliders, and then turned its attention towards the design of an aircraft. Its solution was the Silver Dart, which took to the air on February 23, 1909 in Nova Scotia — the first powered flight in Canada. It got about 30 feet in the air at a maximum speed of about 65 mph. The Silver Dart was then taken apart and shipped back to Bell's home in Nova Scotia. Bell's work in aerodynamics pushed aircraft design forward, improving control and helping to pave the way to modern air travel.

Air conditioning

When fantasizing about time traveling to a simpler moment in history, one thing that stops people cold is the lack of modern conveniences like air conditioning. What many people don't realize is that the history of air conditioning goes back a lot longer than you might think. In fact, Alexander Graham Bell had a working air conditioner in 1911.

"Alexander Graham Bell" explains that Bell, who was Scottish, hated the hot and humid weather in Washington, D.C. where he lived. He tried different strategies to fight the heat. Opening windows just let in the humidity, and in an era when horses still trotted up and down the streets, the smells too. He eventually resorted to draining the swimming pool on his property and setting up his office in the deep end in the hopes that being below ground level would be cooler.

Eventually, Sunday Magazine reports, Bell devised what he called an "ice stove." This was a canvas tank in the attic, filled with ice. A pipe was run from the tank to Bell's pool office, where a blower pulled the cold air into the room. A 1911 issue of Popular Mechanics reports that all summer long Bell's office never got hotter than 61 degrees despite regular temperatures over 90 outside.

Twisted pair cable

Inventing things is a messy process, even after you unveil your working prototypes. The telephone changed the world, but there's a difference between something that works a charm in a controlled setting and something that works out in the field where you can't control variables. Alexander Graham Bell found this out when the telephone started to make its way through the world.

Electronics Weekly reports that people began to notice that when telephone lines ran near electrical lines, the quality of their phone calls dropped significantly due to signal interference. Both telephones and electricity were becoming a growing presence in the world, so the problem was only going to get worse over time. Bell had to come up with a solution.

What Bell came up with was "twisted pair" cabling. PCMag explains that this is when thin wires that are twisted around each other to minimize interference from other wires. Bell received a patent for the invention in 1881. "Dot-Dash to Dot.Com" reports that twisted-pair cabling, augmented with insulating coatings, worked so well that it became standard in all telephone lines and is still used today to provide both land-line telephone service as well as some kinds of broadband internet access.

Hydrofoils

According tot he National Library of Scotland, when Alexander Graham Bell began taking a serious interest in manned aircraft in the late 19th century, he quickly identified a problem: crashing. It doesn't take a genius to realize that falling out of the sky to the ground can be dangerous and even deadly, but it might take a genius to figure out how to avoid it.

Bell's solution was to shift test flights from the hard, unforgiving ground to water. The concept of the hydrofoil already existed — the Canadian Encyclopedia reports that the first attempts to create one date back to 1861. But Bell developed the first working version, which he called the hydrodome. He started work on it in 1908, and by 1911 had a working model that managed 40-50 mph.

Bell kept improving the machine, and Canadian Stamp News reports that in 1919 he set a new world water speed record when it hit about 71 mph. This was at a time when ships powered by steam rarely went faster than 30 mph. The record stood for the next decade, and according to the Alexander Graham Bell Foundation it wasn't until the 1950s that significant development of hydrofoils continued.

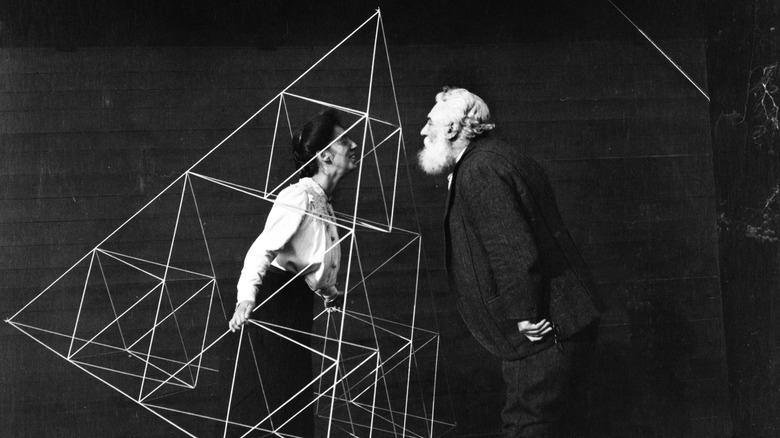

Tetrahedral kite

As explained by Scientific American, people started thinking about using kites to fly themselves around hundreds of years ago. In the late 19th century, Bell turned his attention to creating an aircraft capable of carrying a passenger through the air under power, but a crucial step in his work led to the invention of the tetrahedral kite.

The National Library of Scotland explains that Bell wanted a structure that was light but strong, and scalable enough to carry a man and the engine. He hit on using four-sided polygons called terahedrons — pyramids made up of four triangles — the strongest geometric shape known. The unique properties of the shape allowed the kites to be scaled up dramatically. Bell began designing larger and larger kites using the shape, eventually creating kites large enough to carry humans aloft.

In 1907, Bell created his largest-ever kite, called the Cygnet II. It was towed by a boat over Bras d'Or Lake in Canada, and a man named Thomas E. Selfridge rode on it as it flew. This was a huge step forward in the development of manned aircraft. Unfortunately, as explained in "To Conquer the Air," making these kites into aircraft powered by engines was incredibly difficult, and Bell's team slowly lost enthusiasm for the project despite their history-making success.

Artificial respirator

Many of Bell's inventions were inspired by his clear desire to help people and make lives better. "Alexander Graham Bell: Giving Voice to the World" reports that in 1881 his inspiration came from a tragic place when his infant son, Edward, who had been born prematurely, died from breathing difficulties. Sadly, this wasn't the first time Bell had lost loved ones to breathing problems — both of his brothers died of tuberculosis, making it a personal goal for Bell to devise something that would help people breathe more easily and potentially survive conditions that affected the lungs.

According to the New York Post, the result was a metal vacuum jacket — a cylinder made of iron that was placed around the patient's chest. A hand pump changed the air pressure inside the jacket, mechanically working the lungs. The device was a primitive, early version of the iron lung that would be employed to assist victims of polio in the mid-20th century.