The Real Reason Joseph Pulitzer Communicated In A Secret Code

Joseph Pulitzer, one of America's leading newspaper editors and publishers, faced stiff competition in the world of reporting during the 1870s and 1880s. Notably, he created his own unique codebook to keep his scoops out of the hands of rival journalists, including those who worked for another media titan, William Randolph Hearst.

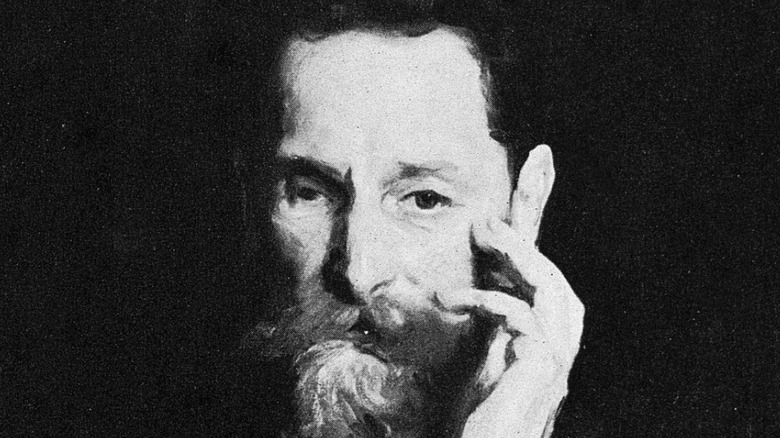

Born in Hungary in 1847, Pulitzer got involved in newspapers not long after he came to the United States in 1864 (via Britannica). He started out as a reporter for a St. Louis German-language daily paper, and he later owned several of the city's publications. In 1878, Pulitzer bought the St. Louis Evening Dispatch and combined its operations with those of the Evening Post (via the Columbia University Libraries). This paper later became known as the Post-Dispatch.

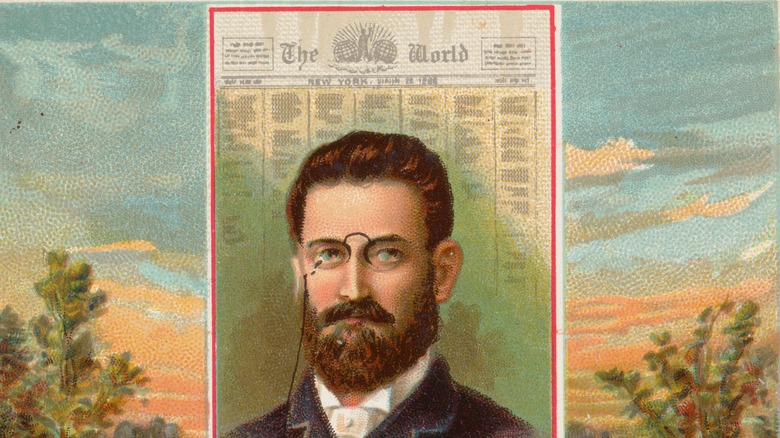

Pulitzer broadened his horizons, jumping into one of the biggest and most competitive media markets of his day with the 1883 purchase of the New York City newspaper, The World. A few years later, Pulitzer established an evening edition of the paper. Being in the news business in New York City presented him with many opportunities and challenges, and he came up with an interesting way to keep information safe when communicating with his staff.

Joseph Pulitzer's code stopped information leaks

In Joseph Pulitzer's time, a lot of information was sent via telegram and telegraph. Understandably, he developed a special code to protect his news stories in case one of these messages fell into the wrong hands. To head off any problems, a person or a thing received a new name, which was listed in the codebook. With roughly 5,000 entries, the book was an alphabetic list of the original people and things and their corresponding code names, according to the Columbia University Libraries. The code names ran the gamut from flattering to insulting to just plain odd. William Rockefeller was known as "Gorgeous," and Roosevelt earned the moniker "Glutinous." A longtime Democrat, Pulitzer gave the opposing side, the Republican Party, the name "Malaria."

Some codebook entries were actually instructions as to where to send information, and others were personal in nature. If Pulitzer sent a message that said "Sedative," it meant "Telegraph my cable address to my family." And a message reading "Sanctuary" meant that "Mrs. Pulitzer is quite well." All replies to his message had to include the word "semaphore," which indicated the reader had reviewed the message twice and understood it. All of his hard work keeping his messages secret paid off, and The World became the country's most widely circulated paper (via The Pulitzer Prizes).