The Untold Truth Of Evangelist John Wesley

According to The Methodist Church in the UK, there are somewhere in the neighborhood of 60 to 80 million Methodists worldwide, making it one of the larger Protestant traditions, accounting for about 2% of Christians globally. Known for emphasizing a personal experience of salvation, piety, and good works — and leading various movements for social reform — Methodists have had a hand in everything from abolition to temperance.

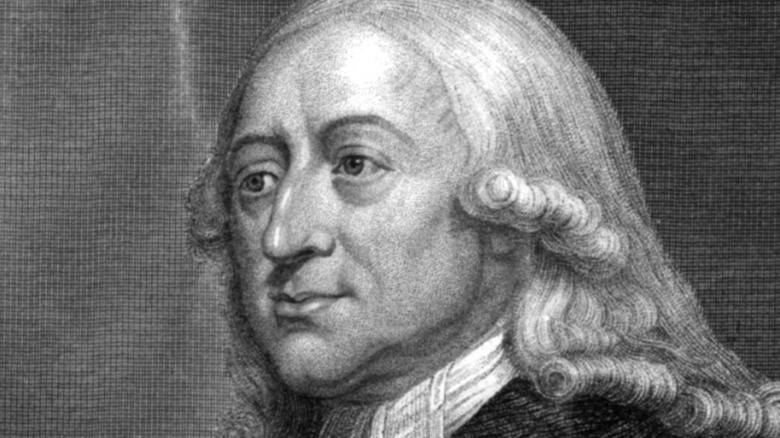

Love them or hate them, it's clear that Methodists have left their mark on the world but how did they get started in the first place? It all more or less goes back to one man, John Wesley, who led a movement that began with a handful of college students, and within his lifetime, took root on two continents before spreading around the world.

Despite being busy founding a new Christian denomination, though, Wesley was active in numerous other fields, changing the face of science and medicine while he was at it. Let's take a look at some of the lesser-known facts about the founder of Methodism.

He almost died in a fire when he was 5

John Wesley was the 15th of 19 brothers and sisters, born in 1703 to Susanna Wesley and her husband Samuel, who was serving as an Anglican priest in the town of Epworth. According to the BBC, Wesley's family never quite felt welcome in the impoverished town, but nevertheless devoted themselves to working for social justice — particularly the care of orphans and widows.

Unfortunately, the town's dislike of Samuel (apparently) boiled over in 1709, resulting in an alleged act of arson that burned down the rectory where they lived. John was in the house at the time, and came extremely close to dying; fortunately, he was on the first floor, and someone nearby managed to pull him out in the nick of time (via Biography Online). From that moment on, Susanna called him "a brand plucked from the burning," and insisted he was destined for great things — which of course every mother does, but in this case, she was right.

"Methodist" was originally an insult

Having survived to adulthood, Wesley attended Oxford University, where he joined a club his brother Charles had founded. The club had originally existed for the purpose of discussing classical literature but had begun to focus more and more on the spiritual lives of its members, mainly due to Charles' (and later, John's) frustration with his classmates' lukewarm participation in religion. The as-yet-unnamed club began to meet for regular Bible studies and, according to Christianity Today, imposed strict rules on its members. Members pledged to take Holy Communion at least once a week (at a time, per SunSigns.org, when this was rare in Anglicanism), to pray daily, to visit prisons regularly, and to spend at least three hours a day in private Bible study.

As you might expect, this club quickly became the butt of jokes among the Wesleys' less-pious classmates, who appended no end of epithets to it, including "Holy Club," "Bible Moths," "Bible Bigots," Sacramentarians," "Super-erogation Men," and, of course, "Methodists" (via the United Methodist Church).

That last one, in case you haven't figured it out, comes from the club's intense, demanding "method" of following the Christian faith — and it stuck as Wesley, somewhat inadvertently, led his followers out of the Anglican Church and into a new denomination.

He was put on trial for being a bad boyfriend

A few years after being ordained as an Anglican priest, John was sent to the relatively new British colony of Georgia, to breathe some life into the parish church there. On the boat, John met 18-year-old Sophia Hopkey (he was 33 at the time), whose parents hired him to tutor her privately in French. Something of a romance began to blossom between the two, especially after they landed in America, but John had decided that marrying would be a distraction from his ministry and broke things off with Hopkey rather than proposing.

This decision worked out about as well for John as you might expect, and shortly thereafter he received a letter from Hopkey announcing her intention to marry a man named William Williamson "if Mr. Wesley had no objection" (via Christian History Institute). Wesley, of course, had plenty of objections but chose not to voice them, so Hopkey married Williamson, who proved to be jealous and began forbidding her to see Wesley, including preventing her from attending church.

Wesley proved jealous as well and ended up embarrassing Sophia in public, rebuking her for her "sins" and denying her communion when she finally did show up for church over her husband's objections. This conduct was bad enough to get Wesley hauled before a judge — who, unfortunately, also happened to be Sophia's uncle, and promptly challenged Wesley to a duel (via 18C Colonial & Early American Women). Wesley chose instead to flee the colony, bailing on his court dates to escape to England.

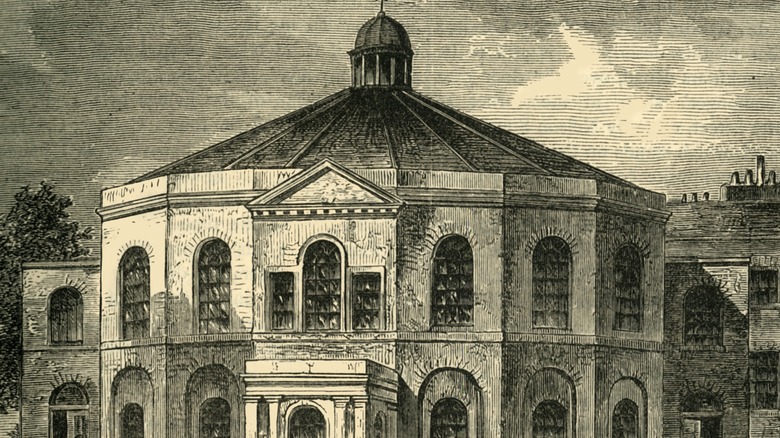

He thought churches should be octagonal

Back in England, Wesley did a considerable amount of soul-searching, and eventually came to the conclusion that, despite being a priest, he hadn't understood the gospel at all; eventually, he found himself at a Bible study with some Moravians (an early Protestant sect), where he felt his "heart strangely warmed," finally understanding that there was nothing he could add to his salvation, and all he needed to do was trust Christ (via Britannica).

Having found this new conviction, Wesley redoubled his efforts as a preacher, eventually connecting with George Whitefield, an Anglican priest who had taken to preaching outside as a means of evangelism. Wesley was initially skeptical of this method (via Christianity Today), but couldn't argue with the results. Over the years, their ministry expanded to thousands in both Europe and America. Wesley never intended to found a new denomination, but when his Bishop refused to allow him to ordain American priests after the American Revolution, it was clear the Methodists needed to leave the Anglican Church behind.

Among other things, this meant designing and building their own church buildings. While other Christians have favored buildings shaped like crosses or auditoriums, Wesley had an unusual penchant for octagonal-shaped buildings (via Christianity Today) — apparently because they were relatively easy to build and allowed for pretty good acoustics (via BiblicalStudies.org). One reason or another, though, it was a distinctive look.

He invented countless medical treatments, many involving electric shocks

Wesley's ministry was driven, in part, by an intense concern for the poor — particularly the soaring cost of medical care, which he strongly suspected was at least partially driven by a racket of doctors and pharmacists conspiring to enrich each other. With that in mind, he opened several clinics and published an influential book called "Primitive Physick," which listed numerous home remedies and folk cures for various diseases (via Deseret News).

Perhaps more interesting, though, was Wesley's interest in electricity, which at the time was on the cutting edge of science. "Who can comprehend," he once wrote (quoted at The American Scientific Affiliation), "how fire lives in water, and passes through it more freely than through air? How flame issues out of my finger, real flame, such as sets fire to spirits of wine?" Wesley read everything Ben Franklin published on the subject (via Christianity Today) and became convinced that electric shocks just might be the cheap miracle cure he was looking for.

If that sounds horrifying, consider that electroshock therapy is still in use for certain psychological maladies today (via New Scientist). In his book "The Desideratum; or, Electricity Made Plain and Useful," Wesley wrote that while electricity was probably most useful for "nervous disorders" (which checks out), he had successfully treated almost everything with it to one degree or another (which doesn't).

Wesley passed away in 1790 at the age of 87, leaving behind more than 100,000 Methodists.