Animals That Went Extinct In The Last 100 Years

Extinct animals — from the tyrannosaurus rex to the woolly mammoth to the dodo — can be as fascinating and puzzling as extraterrestrials. Terrestrial animals of bygone eras can teach us about the past, while also issuing warnings for the future. As the population of humans on Earth has boomed over time, so has the extent of human settlement, colonization, and general interference. That interference has wreaked havoc, either directly or indirectly, on many animal species on Earth. Hunting, exploitation for science and entertainment, and habitat destruction due to human-led agricultural practices are common factors in the extinction of countless animal species and subspecies. Each of these factors relates back, in one way or another, to human greed.

Even so, it can be difficult to identify the cause of a species' decline, and even harder to pinpoint the exact time a specific species went extinct. Endangerment and extinction are often estimated based on human sightings of the species in question, which tend to be unreliable and imprecise. Still, human advancement, industrialization, and commercialization have indisputably wiped out entire habitats and species in the last 100 years. Here are just a few of the animals that are believed to have gone extinct in the last century.

Sicilian wolves were killed off after an environmental crisis

The grey wolf has widely distributed and widely varied subspecies, one of which was the Sicilian wolf. Until its extinction, the Sicilian wolf roamed the Italian island of Sicily, particularly in mountainous and wooded areas, as noted by the Museo Civico di Storia Naturale, or Museum of Natural History, in Verona, Italy. Sicilian wolves were distinguished by their small skulls, slender bodies, and pale coats that have been said to resemble lions' coats. The animals' coats are said to grow increasingly pale and ashen as they age. The wolves' tail has been reported to be narrow and dark at the base, growing thicker and pointier at the end.

The subspecies is widely considered to have gone extinct in the 1920s, as the last known Sicilian wolves were shot near Palermo in 1924. Still, several reports of wolves being killed near Palermo emerged in the late 1930s, followed by multiple sightings of what were believed to be the animals in the 1960s. The primary cause of extinction is believed to be human persecution because the wolves posed a threat to livestock. The wolves' reported inclination to eat livestock may have been the result of an environmental crisis in Sicily that drove the wolves' previous choice of prey to extinction after the Norman period.

Humans wiped out the largest lion subspecies

Barbary, or Atlas, lions were the largest subspecies of lion, once roaming the deserts and mountains of northern Africa. Admired for their huge size and dark manes, the animals were kept in captivity by the royal families of the region, as noted by the Scientific American. It wasn't long before individuals in further nations noticed and coveted the creatures and also began to exploit them. The wild kings of the jungle were brought to battle Roman gladiators at the Coliseum — games which killed thousands of the animals. They were also brought to live and die in captivity in zoos throughout Europe, including the royal zoo at the Tower of London. European hunters killed off the remaining lions, and none were seen between 1901 and 1910.

History books mark Barbary lions' extinction with a tale of a French colonial hunter killing the last creature of the subspecies in Morocco in 1922. But research published in 2013 by PLoS ONE suggested that wild Barbary lions may have lived safe from human exploitation in Algeria and Morocco until as late as 1965. As part of their research, Simon Black and David Roberts interviewed dozens of aging Algerian people who claimed to have spotted the lions after 1922. The researchers concluded that Barbary lions are likely to have died out in Morocco around 1948, and gone extinct in Algeria around 1958, possibly due to forest destruction during the French-Algerian War that year.

Beauty cursed the Australian paradise parrot

Paradise parrots were cursed with what ornithologist, conservationist, and nature writer Alec Chisolm called "the fatal gift of beauty," per The Guardian. Native to the savannas of western Australia, the brilliantly colored bird was on the verge of extinction by the twentieth century. There were no reported sightings of Paradise parrots between 1900 and 1920. This dwindling of the species is largely attributed to European colonization, which killed tens of thousands of Indigenous people in the region and led to the burning of vast grasslands as part of reckless land management practices.

Chisholm began to search for Paradise parrots in 1917 and rediscovered them after a local man reported a sighting in 1921. Still, an increasing number of the birds were being shot, skinned, and taxidermied for scientific research or for display in museums and private residences. Sightings dwindled over the next five years, and the last known sighting of a Paradise parrot was in 1929.

"The Paradise parrot was stunningly beautiful but among its misfortunes was the fact that its habitat was not, and failed to meet the aesthetic standards demanded for contemporary national park declarations," historian Russell McGregor wrote in the 2019 biography "Idling in Green Places: A Life of Alec Chisholm" (via The Guardian). "It was open, grassy woodland of a kind so common that Australians took it for granted. Conservationists could make a case for saving a gorgeous bird, but preserving a prosaic landscape was, in the 1920s and 1930s, a bridge too far."

Humans hunted Thylacines to extinction

The Thylacine, commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf, has been mythologized in its native Australia. With the towering mystique of Bigfoot or the Loch Ness Monster, the animal has been the subject of several unsubstantiated sightings in recent years, as reported by CNN. Thylacines have an unusual appearance, with a dog- or wolf-like head and a cat-like body, per the Australian Museum. The animals were once widespread throughout Australia, and were later confined to the island of Tasmania, but there has been no conclusive proof of the presence of Tasmanian tigers since the last one died in captivity in 1936.

Tasmanian tigers had a reputation for preying on sheep and poultry. European colonists killed thousands of Thylacines for the threat they posed to sheep. But according to the Australian Museum, the Thylacine's appetite for the same animals that humans chose to eat was likely blown out of proportion by a photograph of a Thylacine eating a chicken, which was taken by Harry Burrell and published by the museum in 1921. Humans' hunting of Thylacines for being alleged pests is considered to be the primary cause of the animal's extinction.

In September 2019, Tasmania's Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment published a report documenting eight sightings of the Tasmanian tiger in the three years prior. Still, none of these claims were substantiated by hard evidence, and whether these infamous animals still roam the wilds of Tasmania remains a mystery.

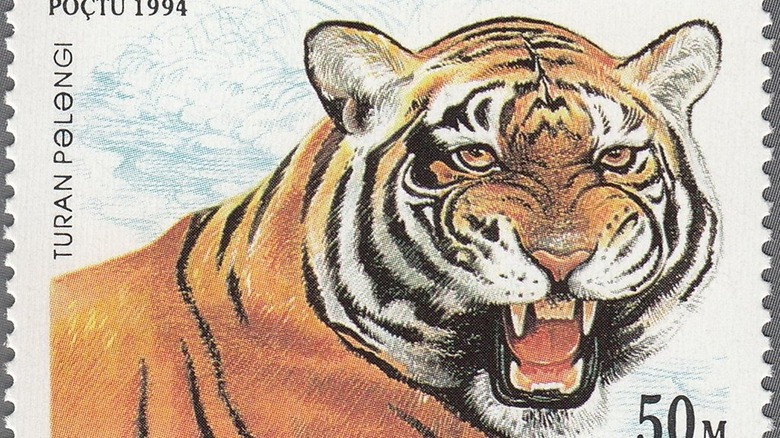

Agricultural projects wiped out the largest tiger subspecies

Caspian tigers were once scattered across a vast swath of central Asia, from Turkey to China, per Popular Science. They lived in wetlands along rivers and roamed through reed thickets, shrubs, and forests, hunting deer and wild boar. According to the Independent, they were the largest subspecies of tiger.

In the first half of the twentieth century, Caspian tigers were poached and poisoned by humans, and the animals they ate were also hunted, making food scarce. The Soviet Union conducted agricultural projects to reclaim land, draining the tigers' wetland habitats to grow crops like cotton. This human interference is believed to have wiped out the Caspian tiger subspecies by the 1950s.

In 2017, Popular Science reported that scientists at the International Union for Conservation of Nature and the World Wildlife Fund were considering reintroducing tigers to Kazakhstan — namely, the Siberian tiger, an endangered subspecies that is closely related to the Caspian. The scientists believe Siberian tigers would be well-suited to the region due to the DNA they share with Caspian tigers, and that introducing them to the area could start a reserve population that may help save the subspecies from rapid extinction.

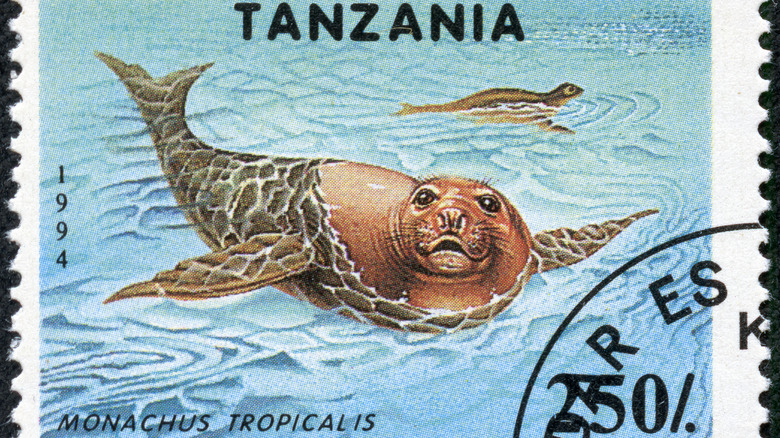

Humans killed Caribbean monk seals for science

The Caribbean monk seal was the first seal species "to go extinct as a direct result of human activities," as noted by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Endangered Species Program. The Caribbean monk seal population was estimated to include 233,000 to 338,000 seals across the Caribbean. They were the only seal subspecies native to the region, which included Florida and the Gulf of Mexico.

As with the many species driven to extinction in the first half of the twentieth century, Caribbean monk seals were fatally impacted by European colonization. The seals were killed for oil and food and captured for scientific study and live display. This exploitation shrank the animals' population, wiped out entire colonies, and left the remaining mammals in fragmented groups scattered across the region. In the early 1900s, collectors traveled to the Yucatan peninsula and allegedly destroyed the last major wild Caribbean monk seal colony. The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service suggests that the killing of hundreds of seals in the name of science in the early 1900s was the final blow to the species. The last confirmed sighting was a small colony on a reef in uninhabited southern Caribbean islands in 1952, and the subspecies was declared extinct in 2008.

Japanese sea lions were hunted for body parts

Little is known about the Japanese sea lion. According to the Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, there is little to no information about the animals' physical characteristics or eating habits, but DNA evidence suggests they were closely related to the California sea lion. According to Duke University's Ocean Biodiversity Information System Spatial Ecologial Analysis of Megavertebrate Populations, Japanese sea lions were reportedly "straw colored with a darker throat and chest in the female," and are believed to have been excellent divers.

An estimated 30,000 to 50,000 Japanese sea lions lived off the coasts of Japan and Korea in the mid-1800s. Within the 100 years that followed, the population dwindled down to just 50 to 60 Japanese sea lions living on Takeshima, also known as the Liancourt Rocks. The last Japanese sea lions were seen in the late 1950s, though some people believe the animal may have survived in unsurveyed Korean waters.

It is widely believed that Japanese sea lions were driven to extinction by unregulated hunting. They were "harvested for their skins, whiskers, internal organs, and oil," and were taken captive for circuses, per the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. According to a 2014 Vice article, endangered sea lions and seals continue to be sold and eaten in Japan.

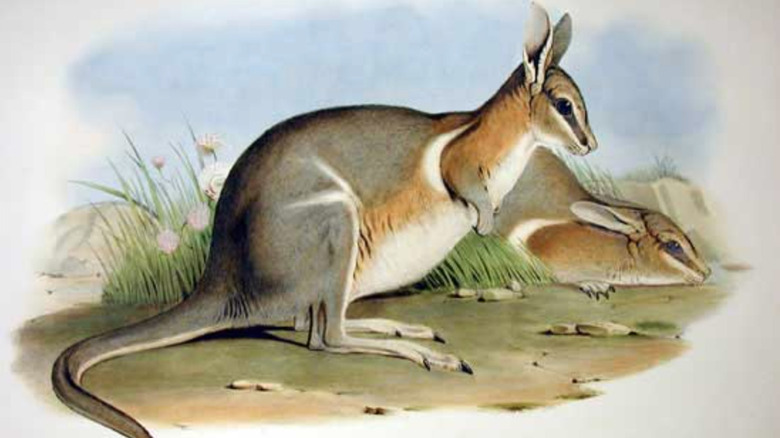

Foxes contributed to the crescent nail tail wallaby's extinction

The crescent nail tail wallaby was named for two distinct physical features: a 'nail' at the tip of its tail; and a white, crescent-shaped patch on its chest, per the New South Wales Office of Environment & Heritage. Before European settlers arrived in Australia, the animal was common throughout the woodlands and shrublands of central, southern, and southwestern regions of the continent. It remained common throughout southwest Australia until the twentieth century.

The last crescent nail tail wallaby in that region was captured in 1908, and the last of the species was caught in a dingo trap in Nullarbor Plain in southern Australia in 1928. After living in the Taronga Zoo, the animal ended up in the Australian Museum. The species continued to survive in the wild for a few more decades, but was presumed extinct by the 1960s, according to a report by the Northern Territory Government.

As with many Australian animals, European settlement was a factor in the extinction of the crescent nail tail wallaby due to habitat destruction through fires and the introduction of sheep to the region. Predation by feral cats and foxes are also believed to have contributed, per the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

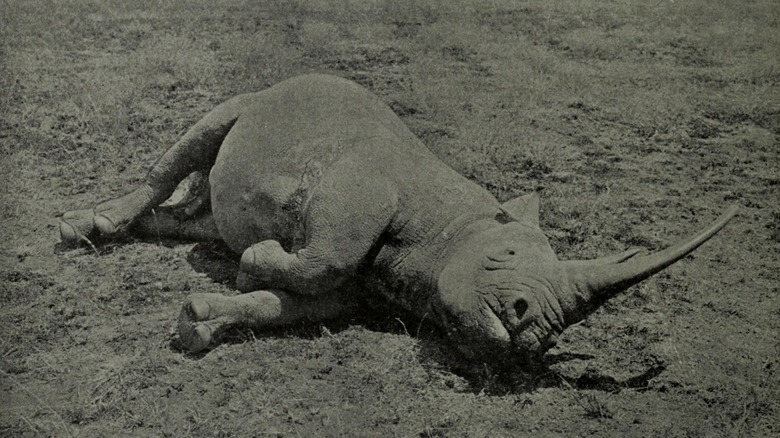

The western black rhino was poached for its horns

In the early 1900s, an estimated one million black rhinos roamed a vast range of savannas across central and western Africa, as noted by Scientific American. But the twentieth century proved catastrophic for the animals as humans decimated rhino populations first through sports hunting, then through industrial agriculture, as well as by farmers who saw rhinos as pests and hunted them.

Another key factor in the rapid slaughter of black rhinos was the rise of Traditional Chinese Medicine. In the 1950s, Chairman Mao Zedong called for the use of TCM over western medicine, even though he did not believe in TCM himself. Poachers flooded to Africa to obtain rhino horns, which were touted as "miracle cures" for ailments ranging from fevers to cancer.

By the end of the century, only 10 western black rhinos remained in the world, all of them in northern Cameroon. Animal advocacy groups such as the World Wildlife Fund called for their protection, but the last time conservationists or scientists saw the animal was in 2001, when the population was down to five rhinos. Over the next decade, professionals searched for the rhinos but found only poaching equipment, wounded animals caught in traps, and poisoned watering holes. The International Union for Conservation of Nature officially declared western black rhinos extinct in 2011.

Climate conditions drove the golden toad to extinction

The extinction of the golden toad was the first extinction to be blamed on humans in relation to global warming, per Science. The toad's habitat in the rainforests of Costa Rica grew hotter and drier as carbon dioxide and greenhouse gases turned up the heat. The altered climate then made way for chytrid fungus, which leads to disease and death in amphibians. As a result, amphibians throughout the Costa Rican rainforest began dying out, with the small golden toad population especially impacted.

The last golden toad was seen in the cloud forests of Monteverde, Costa Rica, in 1989. While the dry conditions were undeniably to blame for the toads' extinction, questions eventually arose about whether the conditions had been caused by human-made global warming or natural moisture patterns. Climate scientist Kevin Anchukaitis and paleoclimatologist Michael Evans of Columbia University conducted research on moisture cycles in the region and concluded that the changes were likely due to El Niño, the weather patterns on the Pacific coast of North America. Monteverde Cloud Preserve biologist J. Alan Pounds disputed the Columbia researchers' findings and suggested that their research methods were not precise enough to measure the impacts of climate change in the region.

In any case, Anchukaitis did not dispute the seriousness of climate change in the region. "The fact that our research suggests it was El Niño and not anthropogenic climate change shouldn't be any comfort when considering the future impact of climate change," he said.

The Guam flying fox hasn't been seen since 1968

The little Marianas fruit bat was a subspecies of flying fox, or fahini, that was native to Guam. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the little Marianas fruit bat weighed just five ounces. The animals inhabited the forests of Guam, where they slept most of the day and lived on a diet of fruits, flowers, and leaves, per the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The last Guam flying fox was seen in 1968, but the animal remains listed as endangered rather than extinct. In September 2021, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service included the Guam flying fox in its proposal to delist 23 species from the endangered species list and declare them officially extinct.

Since humans first arrived on Guam, they established a cultural tradition of hunting and eating bats, and overhunting of the little Marianas fruit bat — and Marianas fruit bats in general — is considered a primary cause of their decline. Another major factor was deforestation on the island, which annihilated much of the bats' habitat. The brown tree snake is also believed to have preyed on the animals and played a role in their presumed extinction.

The Pinta giant tortoise is extinct, but its closest relative may be revived

Galápagos giant tortoises are often divided into 15 subspecies, six of which have gone extinct, according to New Scientist. The Pinta giant tortoise was unique to the archipelago's Pinta Island and had a distinctive "saddle-shaped" shell, which helped the tortoise reach elevated vegetation.

The populations of all 15 subspecies of Galápagos tortoises declined when humans began killing them for meat and introduced destructive animals such as rats and goats to the archipelago. The last Pinta Island tortoise, named Lonesome George, was deemed "the rarest animal in the world" by New Scientist prior to its death in 2012. Lonesome George's death marked the official extinction of the Pinta subspecies.

In 2008, researchers found "saddle-shelled" tortoises similar to the Pinta and Floreana subspecies on Isabela Island. The newly discovered tortoises' DNA suggested they were hybrids descended from their saddle-shelled predecessors. This discovery raised the possibility of reviving Floreana and Pinta tortoises through captive breeding. Further testing in 2015 found that the saddle-shelled tortoises found were descendants of the Floreana, but not the Pinta. In 2017, conservationists announced the possibility of reviving the Floreana tortoise and began the breeding program. The International Union for Conservation of Nature's Craig Stanford said he was "cautiously optimistic about the odds of success."