The Crazy Story Of The Scientist Who Sold Nukes To Everyone

When people think of nuclear proliferation, countries such as Iraq, Iran, and North Korea might come to mind. These countries have all been accused, both credibly and otherwise, of developing and spreading technology for the production of nuclear weapons around the globe. But often forgotten is the nuclear-armed country of Pakistan. Although Pakistan's nuclear arsenal is coming to the forefront today in light of the 2021 Taliban capture of Afghanistan, according to the Brookings Institute, several U.S. presidents have historically turned a blind eye to it in return for Pakistani cooperation against terrorism.

Although Pakistan's nukes have largely escaped scrutiny, the country, or at very minimum, one of its leading scientists, have been among the biggest and best known nuclear proliferators. Pakistan owes its nuclear weapons to Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan. This man's scientific knowledge, combined with lax international regulations, and likely complicity of the Pakistani government would not only turn Pakistan into a nuclear power, but also spread the technology to America's enemies around the globe. This is the crazy story of the scientist who sold nukes to everyone.

Abdul Qadeer Khan's humble beginnings

Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan, also known as A.Q. Khan, was an unlikely candidate to run an international nuclear smuggling ring. The renowned Pakistani scientist was born to a modest Muslim family in 1936, in the British Indian city of Bhopal. Despite his family's humble origins, the Financial Times notes that his father was a school headmaster. Thus, Khan was born to a literate family with a tradition of learning. This background would drive Khan to achieve his full educational potential.

Khan's life changed radically in 1947. According to Stanford University, British India was hastily partitioned upon independence. The Republic of India became a majority Hindu state, while Muslims received the far western and eastern parts of British India, which became Pakistan. The split was anything but peaceful. According to the Financial Times, a young Khan witnessed the horror of Muslim victims of sectarian violence being carried away on trains, among other atrocities. As violence spread, Khan's family decided to leave India.

According to "Shopping for Bombs: Nuclear Proliferation, Global Insecurity, and the Rise and Fall of the A.Q. Khan Network," a 16-year old Khan caught the last train out of town and fled India to Karachi, Pakistan in 1952. During his dangerous, intimidation-filled trip, Indian soldiers robbed refugees of their valuables, including Khan's prized pen, which his brother had given him for his school exams. Despite the hardships, Khan was able to escape and eventually attend college in Karachi. After graduation, he continued his education in Europe.

Abdul Qadeer Khan's graduate career

According to TU Delta, the young Abdul Qadeer Khan studied at West Berlin's Technische Universität and the Netherlands' TU Delft, where he earned a Master's of Science. But he wanted the PhD. As explained in "Shopping for Bombs," he planned to go back to Pakistan to teach, so a PhD was conducive to his career ambitions.

After his master's, Khan enrolled in a PhD program in metallurgy at the Catholic University of Leuven. According to the Dr. A.Q. Khan School, he studied under Prof. Martin Brabers. In the meantime, Khan married a Dutch-South African woman named Hendrina, and established himself in the Netherlands. He defended his PhD in 1972, and moved to Amsterdam, where he had obtained a job with Physical Dynamics Research Laboratory (FDO), which was researching and developing uranium enrichment. This career move would play a major part in his future.

Pakistan's humiliation

As Abdul Qadeer Khan completed his studies in Europe, the Indian subcontinent exploded when civil unrest in East Pakistan escalated into open conflict in 1971. According to Al Jazeera, the triggering event was the East Pakistani Awami League's victory in national elections. The West Pakistani elites, however, refused to hand over power. The army was called in to suppress the resulting political and inter-ethnic violence between local Bengalis and more recent arrivals. This initially localized conflict soon drew India's attention and escalated into war.

As the situation in East Pakistan deteriorated, civilians sought shelter in India. Faced with a possible humanitarian disaster and an opportunity to weaken its Pakistani rival, India intervened on the side of the rebels. According to Time, Pakistan's subsequent defeat and the resulting peace were a national humiliation. The country lost over half its population to the newly independent state of Bangladesh while approxmiately one-third of its military personnel was captured. To add insult to injury, India, spurred by China's 1964 nuclear test, authorized a nuclear program in 1972. According to Global Zero, this program, codenamed Operation Smiling Buddha, yielded a successful nuclear test called Pokhran-1 in 1974. Pakistan's archenemy was now a nuclear power.

Abdul Qadeer Khan's job

According to the Financial Times, Abdul Qadeer Khan wept bitterly upon hearing the news of Pakistan's embarrassing defeat. But he still had to work and pay his bills. "Shopping for Bombs" explains that he obtained his job at FDO on the recommendation of his advisor, Prof. Brabers. This prestigious appointment was the best Khan could hope for — definitely better than a position as an obscure academic. FDO was a subcontractor of the Dutch-English-German consortium UCN/URENCO, which produced equipment for uranium enrichment.

There were a few issues with Khan's appointment to FDO. As the Financial Times notes, much of the organization's research, especially on ultracentrifuges, was considered sensitive, even though it was for peaceful nuclear energy, not bombs. Thus, Khan was barred from sensitive projects at the request of the Netherlands' intelligence agency, the BVD. But there seemed to be little risk of espionage. Khan's wife and in-laws were Dutch, his daughters were Dutch, he spoke fluent Dutch and was well-integrated into Dutch society. He was also not a Soviet, making him an unlikely candidate for a communist spy. Khan was cleared to start work at the lab.

The 'brain box'

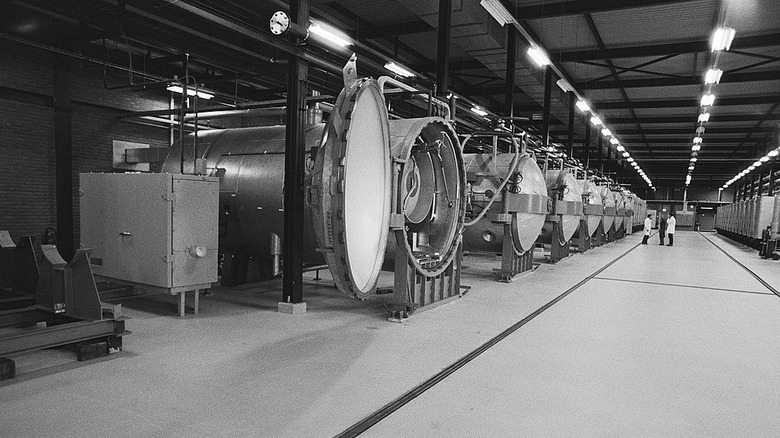

The BVD's fears were partially realized when with just a week on the job, Abdul Qadeer Khan was sent to the Netherlands' primary uranium enrichment facility in Almelo. According to "Shopping for Bombs," FDO had developed a security protocol for him to mitigate the risk of espionage. He was restricted (on paper) to a designated office outside the main facility. He was prohibited from wandering about the facility and entering sensitive areas without an escort. Yet thanks to lackadaisical enforcement, this is exactly what Khan did.

Part of Khan's job was the translation of highly sensitive German documents describing centrifuge designs into Dutch. But according to TU Delta, Khan brought some of these designs home, presumably to copy or share. Colleagues observed him freely roaming the facility, taking notes "in a foreign script" (probably Urdu), suggesting that he was up to something nefarious. According to the Financial Times, alarm bells should have gone off when it was revealed that Khan did most of his work in Almelo's "brain box," the storage area for the facility's most sensitive materials. But for some bizarre reason, Khan worked undisturbed, at least initially. An employee from behind the Iron Curtain may have drawn suspicion, but certainly not a Pakistani. Only Khan's officemate, photographer Frits Veerman, had any reservations.

Frits Veerman's suspicions

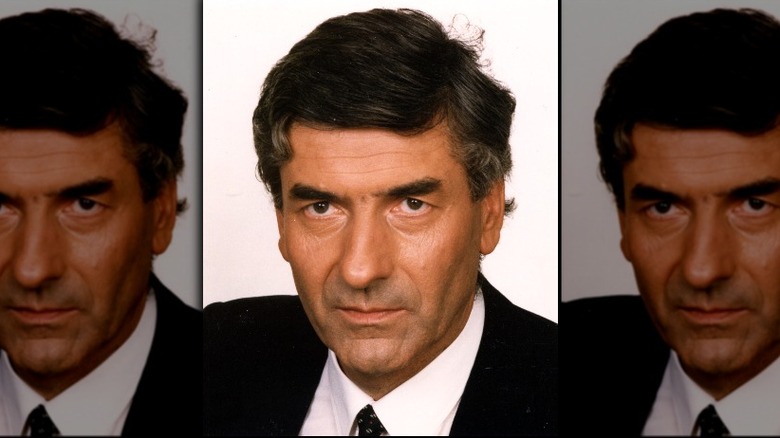

Abdul Qadeer Khan and Frits Veerman (pictured) had become friends. According to IPFM, Veerman frequented Khan's house for dinner and was considered a family friend and confidant. According to the Financial Times, the two co-workers played tennis on their days off. Khan dropped his guard around Veerman, even telling his colleague that he kept a gold ring as "pocket money" if he needed to "leave quickly." It would soon become clear what Khan meant.

In 1973, Veerman noticed drawings and plans of centrifuges and other classified material scattered around Khan's house. At first, Veerman was puzzled. But his suspicions soon proved correct when Khan asked Veerman to photograph sensitive materials for him, which he refused. Veerman also overheard Khan's calls with Pakistani embassy officials, and he decided to blow the whistle. But Khan was his superior. The head of FDO had known Khan as a student and hired him on Prof. Brabers' strong recommendation. He had even allowed Pakistani delegations to tour the plant and take discarded centrifuge parts back home. According to IPFM, FDO ordered Veerman to burn evidence in his possession and leave Khan alone. FDO eventually fired Veerman in 1978.

IPFM notes that in 1975, the Dutch government noticed a series of suspicious transactions that FDO could no longer ignore. The Pakistani embassy in Brussels had placed orders for parts that matched components used in classified URENCO centrifuges. Veerman's hunch had been proven correct. Khan had committed industrial espionage and was passing URENCO's secrets to Pakistan.

Abdul Qadeer Khan slips away

Once Pakistan's orders came to light, Dutch intelligence planned to arrest Abdul Qadeer Khan. At the 1975 nuclear trade show in Basel, Switzerland, they had their smoking gun. According to "Peddling Peril: How the Secret Nuclear Trade Arms America's Enemies," Khan was caught asking prying questions regarding the identities of URENCO's suppliers. Dutch intelligence quickly connected the embassy orders with Khan's requests and prepared to arrest him upon his return to the Netherlands, according to the Financial Times.

Under pressure from economic minister Ruud Lubbers, the Dutch government threw away its chance. According to Lubbers himself (via "Peddling Peril"), it was pure oversight. Lubbers "did not think about nuclear proliferation... to be honest." He was more concerned that the centrifuge technology would fall into the hands of URENCO's American and Japanese competitors. This was in violation of Dutch obligations under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, which obliged signatories to stop the spread of nuclear weapons. The Financial Times notes that Lubbers was also saving face. He wished to avoid an embarrassing and potentially damaging scandal to the Dutch technology sector. Instead, Lubbers ordered Khan monitored, but found no clear evidence of espionage after Basel.

Lubbers was allegedly not alone in opposing Khan's arrest. Fearing nuclear proliferation, the BVD had shared information with America's CIA. But Lubbers claimed that the agency decided to leave Khan alone. While Albright believes that Lubbers was shifting blame, he notes that the CIA allowed Khan to operate with impunity in the 1980's, suggesting that Lubbers' claim was at least partly true. Regardless, it was a missed opportunity to stop nuclear proliferation. Khan went on "holiday" with his family to Pakistan and never returned.

Creating a Pakistani nuclear program

Contrary to Lubbers' fears, Abdul Qadeer Khan had no interest (yet) in sharing his pilfered designs with America, Japan, or anyone else. His goal was a nuclear-armed Pakistan to counterbalance India's capabilities in the subcontinent. According to the Financial Express, Khan had written to Prime Minister Zulfikar Bhutto in 1974, offering to build a Pakistani nuclear bomb. Despite Khan's obscurity, Bhutto accepted the offer and set Khan up with a lab called the Khan Research Laboratory (KRL).

Khan faced a number of problems. Initially, he was able to obtain parts from European suppliers, but many of these were quickly banned for export. Khan found an ingenious workaround. He simply ordered sub-parts and duplicated the equipment in Pakistan. Khan's brother couriered designs and other information from the Netherlands on KLM flights. Equipped with a diplomatic bag, he was exempt from customs searches. The gulf states bankrolled Pakistan's nuclear program through shady Pakistani banks, and Libya's Muammar Gaddafi helped Pakistan obtain uranium from Niger when Germany shut off supplies. So Pakistan was hardly alone in this venture.

The program was a resounding success. In 1998, Pakistan conducted its first public nuclear tests at Chagai. But there were repercussions. According to Global Security, the United States cut Pakistan's foreign aid in 1977. The Conversation notes that across the world, there was the fear of nuclear proliferation among hard-line Islamic states following the Iranian Revolution of 1979. These fears became justified when it was later discovered that the KRL had given material to U.S. rivals.

KRL and nuclear proliferation

In the late 1980's, the KRL began selling Abdul Qadeer Khan's technology to other nations with interest in uranium enrichment, including several hardline enemies of the United States. According to Outrider, this business was conducted in the open. The KRL held international conferences where it openly advertised the lab's capabilities and offered enrichment technologies to anyone willing to pay. It even publicly advertised at international arms shows, suggesting that the lab had some sort of official backing.

The KRL's public relations campaign paid off in 1987, when it closed a deal with its first client: the Islamic Republic of Iran. According to OpenDemocracy, Khan met with Iranian representatives in a hotel room in Dubai. The Iranians paid $3 million for the centrifuge designs. A second deal was inked in 1993 for actual parts. In 1992, North Korea cut a deal to provide missile technology in return for enrichment equipment. But for whatever reason, no-one linked the deals to Khan. Perhaps Khan should have quit while he was ahead. But he (or his superiors) decided to take on a new client, Libya's Muammar Gaddafi.

According to Global Security, Khan supplied Libya, which was still under international sanctions, with centrifuge parts produced in Malaysia. American and British intelligence already had suspicions about Libya's nuclear program and suspected Khan of being the nation's supplier.

Abdul Qadeer Khan's downfall

According to the Arms Control Association, the United States knew of Abdul Qadeer Khan's activities by 2000. But U.S. president George W. Bush decided to drop the issue in 2001. According to NTI, Bush did not press Pakistani president Pervez Musharraf about Khan's activities nor request access to the scientist, who was by now a Pakistani hero. Why? According to a CRS report, Pakistan was a key U.S. ally in the recently-begun War on Terror in neighboring Afghanistan. NTI notes that hunting Osama bin Laden, al-Qaeda, and the Taliban was considered of greater importance, so Khan remained a free man.

2003 would prove a turning point in Khan's life. That year, U.N. weapons inspectors searched the Iranian nuclear facility in the city of Natanz. According to Global Security, the inspectors discovered that Iran had been assembling P-1 and P-2 centrifuges in the facility. No link to Khan and the German models from Almelo, right? Not exactly. According to the Carnegie Endowment, the KRL had modeled these centrifuges on the German prototypes Khan had worked with in the Netherlands. Thus, Iran could only have obtained this specific technology through Khan's network.

That same year, the Italian navy stopped a ship carrying Malaysian centrifuge parts. According to the BBC, it was bound for Libya, presumably as part of Libya's nascent nuclear program. Once again, the components of the ship matched those used in Pakistan and URENCO. Caught red-handed, Gaddafi renounced Libya's nuclear program and possibly tipped off the United States as to the cargo's origins. Khan was once again in the spotlight.

Pakistani complicity

By 2004, President Pervez Musharraf could no longer defend Abdul Qadeer Khan. Seeking to bury the story to avoid disrupting relations with the United States, Musharraf removed Khan from the KRL. Khan then confessed on national television to running the smuggling ring alone and was pardoned for his crimes. But Khan had a trump card and was unwilling to be a scapegoat. He knew everyone who was complicit in the scheme, including members of the Pakistani army and government.

Although Khan officially acted alone, he soon retracted his statements. According to India's Economic Times, Khan claimed to have acted with the blessing of the Pakistani government. In fact, Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto had ordered the proliferation in the early 1990s. But the story gets crazier. In 2011, Khan claimed that North Korea had paid Pakistani military officials to the tune of $3 million for the technology transfer (via the Washington Post). Khan even produced a letter validating his claims, although its authenticity is disputed.

In 2006, former IAEA chief Hans Blix injected himself into the debate. According to the Hindustan Times, he determined that Khan could not possibly have acted alone, despite his "confession" to the contrary. In 2008, Khan appeared to be vindicated. Journalist Shyam Bhatia, (via NTI), wrote that Bhutto had personally smuggled nuclear secrets on CDs into North Korea in 1993. If true, it suggests that Musharraf had thrown Khan under the bus to cover up potential government complicity.

Is Abdul Qadeer Khan a hero or a villain?

Although Abdul Qadeer Khan did not act alone, his own words indicate that he was more than happy to commit nuclear espionage and proliferation. Writing in Newsweek, Khan defended his actions as protecting Pakistan from Indian "nuclear blackmail." Pakistan could not be left at the mercy of a nuclear armed India and expect such an arrangement to end well. A nuclear-armed Pakistan would not have lost half its territory in 1971. So what was Khan's opinion on proliferation? Khan noted in Newsweek that no nuclear-armed state has ever been invaded or occupied. A nuclear-armed Iraq or Libya "wouldn't have been destroyed in the way we have seen recently." In this regard, Khan was correct, as both of his former clients (the Iraqi deal fell through in 1992) have fallen victim to regime change wars. Perhaps Khan really believed that nuclear proliferation would result in a more peaceful and restrained world.

Today, Khan is a regretful man. According to Indian Newspaper Awaz, Khan bemoaned placing nuclear capabilities in the hands of the corrupt Pakistani military. It seemed to him that the Pakistani army no longer felt threatened by India, and was instead focused on holding its own people hostage to preserve its political power. Nevertheless Khan remains a Pakistani national hero. Despite his participation in nuclear proliferation schemes, Pakistanis see him as a patriot who earned Pakistan international respect in its darkest hour. Can both narratives be true at the same time?