What John Hinckley Jr.'s Life Was Like Inside A Psychiatric Hospital

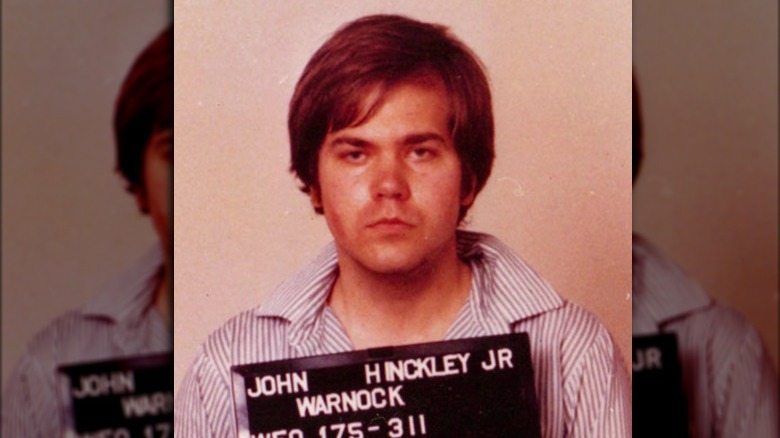

On March 30, 1981, shots rang out outside the Washington Hilton Hotel. Standing amid a sea of reporters, would-be assassin John Hinckley Jr. shot President Ronald Reagan in the lung, just missing his heart, seriously wounding three others (via History). The crime, motivated in part by Hinckley's obsession with actress Jodi Foster after seeing her in "Taxi Driver," Rolling Stone reported, resulted in Hinckley's subsequent institutionalization at St. Elizabeth's Hospital in Washington, D.C., where he was committed for 34 years after being found not guilty in 1982 by reason of insanity.

Initially allowed out of the facility in 2016 to live with his mother, Hinckley was unconditionally released on September 27, 2021. Since 2003, NPR writes, Hinckley had slowly been given more and more autonomy over the last 18 years, with the Department of Behavioral Health eventually determining that he posed "low risk for future violence."

For many people, the idea of a person being committed to a mental health hospital instead of going to prison seems a light sentence, but life inside a mental institution is not as simple, or easy, as most people assume. Hinckley may not have been incarcerated traditionally, but it's still a regulated life, contained behind walls, with restricted movement and predetermined activities.

The institution he was at houses many of D.C.'s criminally insane

St. Elizabeth's Hospital is the primary mental health hospital for the D.C. area, and was formerly known as the Government Hospital for the Insane, the National Park Service (NPS) writes. According to the Department of Behavioral Health (DBH), it is the "District's public psychiatric facility for individuals with serious and persistent mental illness who need intensive inpatient care to support their recovery." In existence since 1855, the current hospital is a modern 450,000-square-foot facility, with light-filled spaces, enclosed courtyards, and personal green spaces. According to 2008 statistics, just under half of the patients at the hospital are considered "forensic," i.e., having been found by a court to be not guilty by reason of insanity.

For patients like Hinckley, there are many restrictions they have to abide by. Visitors are limited, though Biography notes Hinckley himself had at least one girlfriend during his time there, and dated other women, primarily those who were similarly in treatment for mental health issues, the LA Times reports.

Some patients are allowed off-campus visits or excursions like shopping (via The Washington Post). In 1999, Hinckley was allowed to visit his parents outside the hospital, though that was eliminated in 2000 when he was found with a book on Foster, his former obsession (via Biography). When he was conditionally released in 2016, his restrictions including monitoring his location and his computer's browsing history. However, the new ruling eliminates those limitations.

Life inside a mental health institution is relatively boring

Author Mikita Brottman talked to A&E about her experience visiting a criminal mental health facility for her book, "Couple Found Slain: After a Family Murder," and detailed what it's like for inmates. She noted that after an early breakfast — which is eaten with a spoon, as forks and knives are not allowed — patients attend a number of different groups, whether group therapy, study time or leisure clubs like outdoor time, fitness or book clubs, but also have a lot of free time (via Psycom). However, during those periods they are required to be in the public areas of the hospital, not in their rooms. "Basically, it's pretty monotonous and there's a lot of downtime with nothing in particular to do," Brottman notes.

Similar to prisons, many patients also have in-house jobs in a wide variety of areas, everything from janitorial to medical records. Hinckley himself held a clerical-type job (via Biography). All patients also have at least weekly meetings with their primary psychiatrist.

One of the biggest differences, Brottman notes, between hospitalization and imprisonment, though, is that there is no designated sentence time. People who are institutionalized stay there indefinitely until a mental health professional determines that they are no longer a threat and are mentally well enough to be released into society. That could take days, weeks, or months, but in some cases it can take years, or, like Hinckley, even decades.

His hobbies, however, were generally encouraged

During his time being institutionalized, John Hinckley developed a number of passions, particularly for painting, songwriting, and photography. As the LA Times notes, doctors at the hospital believed those interests to have therapeutic value as well, so they were supportive. However, there were still restrictions. Hinckley was not able to actually play music in the hospital, nor was he able to display his artwork publicly. While that has changed since his initial conditional release in 2016, and he now has his own YouTube channel, as per a judge's orders he was not allowed to profit off his music in any way, nor have conversations with any of his followers.

During his time at the hospital, Hinckley also looked after a feral colony of approximately 24 cats, the Washingtonian reports. "They love me. They come up to me, get my rub. I pet them all the time," he told one of his therapists in 2015. Because his doctors felt he needed more structured activities outside the hospital in order to be able to properly return to society, he was gradually allowed more and more off-campus excursions, and he used some of that time to stock up on cat food at the local Petco.

However, not all of Hinckley's interests were as benign. Biography writes that he became pen pals with notorious serial killer Ted Bundy, a correspondence that continued until Bundy's execution in 1989.