The Mythology Of Loki Explained

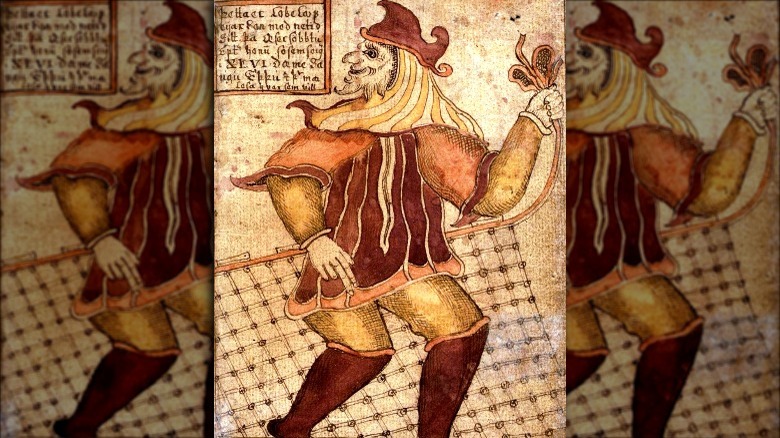

Nowadays, people love Loki. Sure, he can be a bit of a jerk, but he comes through in the end for his fellow superheroes and has a really nice accent in the meantime. But, in truth, the Loki of modern day pop culture is very, very different from his mythological predecessor. Sure, they've both got that trickster business going on, but can you really imagine Tom Hiddleston's Marvel character being truly evil or turning into a mare to produce an eight-legged horse? We didn't think so.

Now, while you're certainly welcome to enjoy the version of Loki that's been gracing the big screen and your streaming service lately, just know that his suave British demeanor is far removed from the wild Loki of myth. If you were to encounter the mythological Loki, at least as he's presented in medieval documents and Norse tales, you'd be dealing with a fearsome figure indeed.

Mythological Loki is often a darker character with some surprising connections to Norse history, culture, and literature. He's also got a pretty strange and oftentimes menacing family that, according to the myths, will play significant roles at the end of the world, known as Ragnarök. And, no, he isn't just a simple trickster figure, like an old Norse Bugs Bunny. Here is the true, complex, and fascinating mythology of Loki explained.

The real world history of Loki's character is obscure

Some people may assume that mythology is pretty well set in stone. That is, the characters and stories contained in any kind of culture's folktales and mythos have surely been around for many centuries and haven't undergone all that much change. But, humans being human, the way we tell stories inevitably changes over time. And, in the case of Loki, it's not clear when or how he was added to the Norse myth canon.

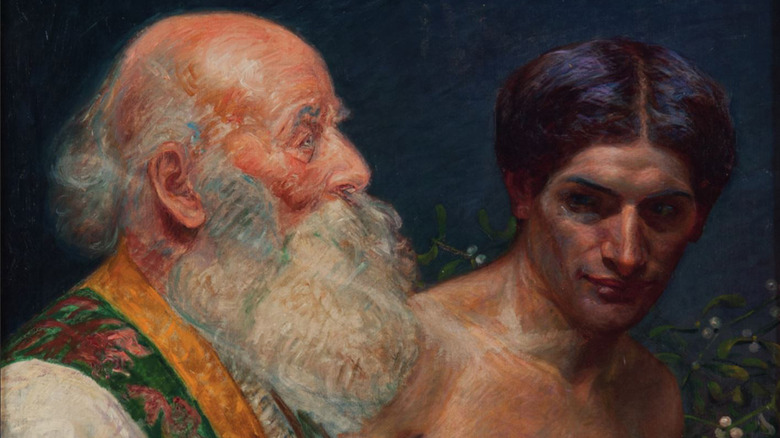

That's partially because the best source of information we have about Loki and Norse mythology in general comes from the Middle Ages. Specifically, as the World History Encyclopedia reports, that would be "Prose Edda," a 13th century compilation of pagan Norse tales compiled by Christian Icelandic historian Snorri Sturluson. Loki also pops up in some earlier examples of Norse poetry, but he's oddly missing from early sources and those outside of Scandinavia. If you were to look at Germanic myths, for instance, you'll see Odin and Thor — but no Loki.

What makes it all the more complicated is the apparent fact that no one really seemed to worship him. Other gods had devoted followers, but Loki appears to sit in a weird area between divinity and trickster figure. According to Gizmodo, he might have been a fire god, but that's far from certain. Ultimately, Loki's origin story is still shrouded in mystery.

The mythical family of Loki gets awkward

Even if we set aside all the complications of Loki's place in the written record, the details of his background in the mythical stories themselves can get frustratingly vague. And, no, it really doesn't help at all to mix up the Norse myths and the more modern day fables told about Loki in the ultra-popular Marvel movies and television shows.

Going by Snorri Sturluson's account in "Prose Edda," Loki is apparently the son of a giant named Fárbauti and an even less well-defined mother named either Laufey or Nál (via the World History Encyclopedia). Loki marries Sigyn and has a son named Narfi. Later on, Sigyn proves to be remarkably faithful and sticks by her husband when he's bound to a rock and positioned just beneath a poisonous flow of venom.

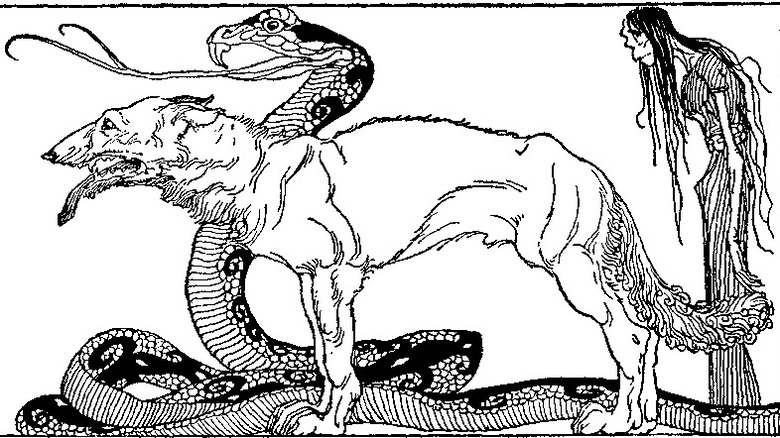

We say remarkable, because Loki apparently doesn't have any qualms about fathering children outside of marriage. Namely, he takes up with a giantess named Angrboda. Together, the pair have three very unusual children: a giant wolf named Fenrir, a similarly huge snake called Jörmungandr or the Midgard Serpent, and a daughter, Hel, who will eventually rule over the underworld (at least in later additions to the story). And they all have a step-brother who probably makes the family reunions even more awkward: Sleipnir. That would be the eight-legged horse who was birthed by Loki, who had himself briefly taken on the form of a mare and gotten very cozy with a stallion named Svaðilfari.

Loki has a complicated role in Norse mythology

Though he's often introduced as a trickster figure, the reality of Loki's role in the Norse pantheon is less obvious and more complicated than just being the trouble causing Bugs Bunny of Scandinavia. Of course, he is indeed a mythological figure who seems to delight in playing tricks both large and small, as Smithsonian Magazine reports. And that's very clearly a mythical role that's proven important in a great variety of cultures and belief systems across the globe, from Native American trickster figures to the storm god Susanoo in Japanese Shinto belief.

But, while there are plenty of popular retellings of Norse myths that basically paint Loki as a cartoon devil dancing around and gleefully waving a pitchfork, that's not all there is to his character. In fact, the Aesir (the gods who inhabit Asgard, though it's worth noting that they aren't the only gods around in the pantheon) actually owe Loki a debt.

The Aesir may not want to admit it, but Loki saved their butts on multiple occasions. "Norse Mythology: A Guide to Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs" notes that he saved the Aesir from themselves, helping distract a contentious wall-builder and dressing up as a handmaiden to help Thor regain his magical hammer, Mjölnir. And, sure, some problems were Loki's doing (like when he oddly decided to cut off one goddess' hair), but he has at least demonstrated a willingness to often fix his own misdeeds.

Loki's daughter is in charge of the underworld

According to "Norse Mythology: A Guide to Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs," Hel is the daughter of Loki and the giantess Angrboda. The most complete version of her story comes from the medieval Snorri Sturluson and his "Prose Edda." Sturluson claims that Odin and the other Aesir were alerted to Loki's spooky children with Angrboda by a prophecy that said the three would cause considerable trouble in the future. So, in a preemptive strike, they chain Fenrir to a rock and toss the Midgard Serpent into the ocean (this was apparently when the serpent was quite a bit smaller than its world-encircling final size). Hel is also imprisoned, in a way, though she gets the entire underworld to move around in. Plus, she gets a job — all of those Norse who died off the battlefield go to her gloomy realm (Valhalla being reserved for those who met heroic ends).

Hel, not unlike her father, may be a later addition to the Norse canon. In fact, as the World History Encyclopedia argues, she could be a very late addition, perhaps being a whole-cloth invention of Sturluson. Even if she does carry through elements of pagan Norse belief, like the existence of an underworld, chances are good that Sturluson and other later authors tweaked things to fit with a Christian worldview predicated on the existence of a heaven and hell.

Loki's children play a part in the end of the world

Undeniably, Hel are her underworld realm are plenty spooky. But like so many fearsome beings in world myth, she serves a purpose, both within the Norse cosmos and as a mythical character. So, too, do her equally intimidating brothers, Fenrir and Jörmungandr.

The siblings have a significant role in bringing about Ragnarök, or the end of the world as the gods know it. According to one version of the "binding of Fenrir," the gods, frightened by a prophecy that says Loki's children will be bad news later on, challenge the increasingly large wolf to a game of strength (via the World History Encyclopedia). It's a trick, of course, and Fenrir is chained to a large rock. He will break loose at Ragnarök, however, and will gobble up Odin before meeting his own end at the hands of Vidarr, Odin's son.

Jörmungandr, also known as the Midgard Serpent, is another of Loki's stupendously huge sons. Per the World History Encyclopedia, he's also taken away by the gods and tossed into the ocean. There, Jörmungandr grows ever larger, until he can encircle the entire world. Eventually, at Ragnarök, and perhaps nursing a serious grudge, he'll also make it to the battlefield, where he faces off against Thor. The god of thunder is victorious against the Midgard Serpent, but is so covered in the snake's venom that he drops dead on the spot, too.

Odin's horse has an awkward connection to Loki

Even when considered among a truly odd brood of giant animals and half-corpse rulers of the dead, Sleipnir may be the strangest of Loki's offspring. Or, at least, his origin story is a truly awkward one to tell at the family reunion, and it's not just because he's a magical horse with eight legs.

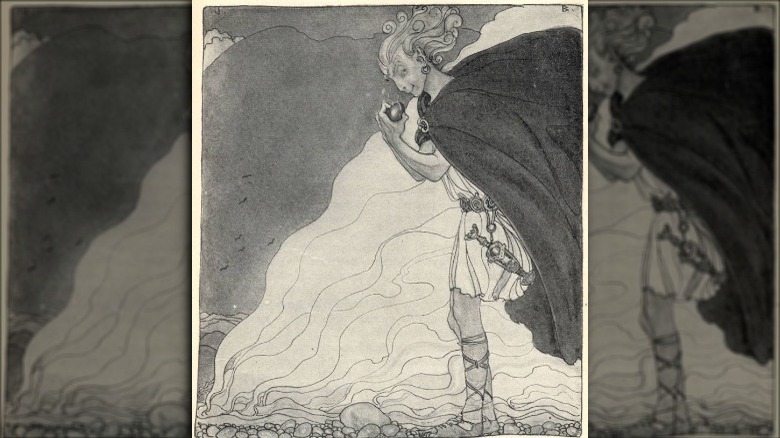

According to the World History Encyclopedia, the gods of Asgard wanted a wall built around their home. A mysterious contractor appeared and offered to do it in exchange for the beautiful goddess Freyja, the sun, and the moon if he completed the wall by a specific date. Loki convinced the Aesir to agree, saying that he had a cunning plan in store to get the wall done, keep Freyja in Asgard, and save the gods some money.

The plan, it turns out, is to distract the builder's super strong and very efficient horse, Svaðilfari. And, to do that, Loki magically transforms himself into a mare. But, where Bugs Bunny would only blink his eyes alluringly at some poor dupe, Loki, well, goes quite a bit further and becomes pregnant. The result is Sleipnir and, for the builder, a missed deadline. Odin takes Sleipnir as his own ride, finding that the horse is fantastically fast and can transport people to magical realms like the underworld.

Loki is notorious for the death of Balder

While Loki often comes off as an annoying but still occasionally fun trickster or even helper in Norse myth, there's one tale in which he comes across as an outright villain. And, for one unfortunate god, the tale turns out very poorly indeed.

The sad sack in question is Balder (also known as Baldr). According to ThoughtCo, he was the most beautiful of the gods and also the son of Frigg and Odin. He was also beloved by just about everything and everyone, meaning that Balder was probably invited to all the parties and warmly welcomed every single time. Frigg, however, wanted to make sure that Balder would be fine, so she went around and asked any harmful thing in the world, from stones to Thor's various deadly weapons, if they would agree to leave Balder alone. They did, and Frigga returned home, relieved, and held a party in celebration.

The gods, apparently never having heard of the concept of hubris, fling deadly things at Balder and delight when nothing hurts him. But Loki can't stand a good time. Doing some investigating, he discovers that Frigg hadn't bothered to ask the seemingly harmless mistletoe to lay off Balder. So, Loki gathers a sprig of mistletoe and, in an especially evil twist, gets Balder's blind brother, Hod, to throw the fatal chunk of wood. Balder dies right away and, despite attempts by the Aesir, can't be retrieved from the underworld.

There's a whole poem of Loki trading insults with other gods

In one poem included in "Prose Edda," there's an entire sequence in which Loki and the other gods talk smack about each other. Known as the "Lokasenna," it's the tale of a party where Loki is not invited, but shows up anyway and does his level best to ruin everyone's good time. He gets drunk and accuses the other gods of sexual impropriety, sorcery, and cowardice, among other things. Everyone argues with Loki, but it only ends when Thor threatens to knock the trickster's head off with his hammer. Loki concedes that he actually takes Thor seriously, and so leaves.

There then follows a short prose section that almost casually mentions what happened to Loki afterward. He turns into a salmon to evade the Aesir, but is caught anyway, and then tied up with the bowels of his own slaughtered son. A snake hangs above his head, dripping venom. Loki's only relief comes when his wife, Sigyn, holds up a bowl to catch the poison. When she has to dump out the contents of a full bowl, the venom hits Loki, he writhes, and earthquakes occur.

As Loki himself might point out, the gods were engaging in a fairly well-established practice known as flyting, which Atlas Obscura notes was a semi-ritualized exchange of poetic insults practiced in a number of northern European cultures. It's effectively a medieval Norse rap battle.

Other gods eventually got sick of Loki's interfering

Though Loki had proven to be helpful, the time still came when he became a liability. After all, Loki had engineered the death of Balder, and he had produced those three ominous kids. His increasingly evil nature seems to be more the product of later works, and may even be an attempt to link him to the Christian devil, per the World History Encyclopedia. Regardless, the Aesir concluded that it was better to keep Loki contained.

According to "Norse Mythology: A Guide to Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs," Sturluson's version of the myth has it that the capture and binding of Loki happened some time relatively soon after the flyting incident. After the events outlined in the "Lokasenna," Loki stays bound to the rock with venom dripping above until Ragnarök, presumably ruminating on all the wrongs done to him and nursing a serious grudge the whole time.

Loki gets his revenge at Ragnarök

Eventually, Loki is able to break free of his prison at the outbreak of Ragnarök, the end of the world. That is, the end of the world at least as far as most of the gods are concerned. According to "Prose Edda," Loki leads a group of "Hel's own" (presumably an army of the undead) to the battlefield of Ragnarök,where they have a bloody showdown with seemingly everyone.

At this point, Loki has completely changed sides from working with the Aesir, at least most of the time, to fighting against them. After all of the binding and the imprisonment of his children, among other things, it's maybe easy to understand why such a change would have happened. But, even if you have a brief moment of sympathy for this devilish trickster, things still end pretty poorly all around.

According to "Prose Edda"'s account of things, Loki finally meets his end while facing off against Heimdall, the watchman of Asgard who guards the entrance into and out of the realm (via Britannica). They manage to wound each other seriously enough that both die and exit the story rather quickly. Meanwhile, Jörmungandr and Thor face off and also kill one another. Fenrir does away with Odin on the battlefield, but is then quickly killed by Odin's son, Vidarr (via the World History Encyclopedia).

Loki points to a complicated view of Norse sexuality

Though it may be easy to fall into the trap of thinking that the Norse were strictly heterosexual and highly patriarchal, don't fall for it. In reality, the love lives and sexuality of Norse people were more diverse than you may initially think. And, if you were to take a closer look at some of the details of Loki's story, you could find some hints to just that effect.

First, as "Norse Mythology: A Guide to Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs" points out, there's the matter of Loki easily changing his shape to become a mare in the story of Svaðilfari. And, what's more, he bears a foal from that encounter. In another story, Loki and Thor both dress in women's clothing to trick an opponent. Loki wouldn't be alone in this gender ambiguity either, as chief god Odin practices a type of magic known as seiðr or seid. According to Viking Archaeology, seiðr is traditionally associated with women and focuses on illusions and prophecy.

As for real-world Norse people, they clearly understood the concept of same-sex relationships, though Fordham University notes that their agricultural society apparently pushed many into opposite-sex reproductive partnerships out of necessity. That said, it's worth remembering yet again that much of our information about Norse life comes filtered through medieval Christianity, which was not shy about its homophobia. It's quite possible that earlier notions of sexuality were quite a bit more accepting.